|

Till the Last Gasp is a new release from Darrington Press by designer Will Hindmarch, with additional design work by Alex Roberts. It’s an RPG packaged up like a board game with board game elements, like dice, tokens, cards, glossy paper settings, and folding cardboard playmats. The game is designed to help players tell the story of a climactic duel between two characters who have decided that there is no other way to settle their differences.

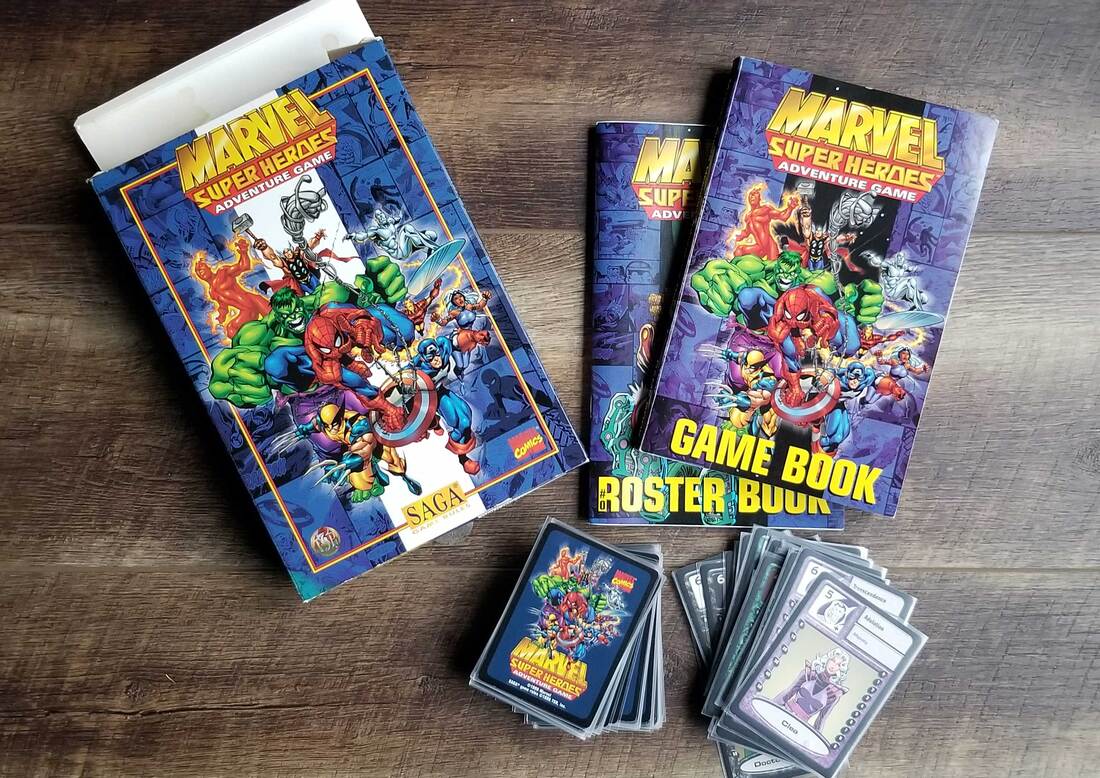

The first dedicated dueling game that I had seen is “A Single Moment,” by Tobie Abad. That game is specifically about two samurai warriors who were once friends in a fight to the death. Play itself consists of flashback scenes that create the narrative behind the duel, how the friendship fell apart, what lines were crossed and trusts betrayed. In those flashback scenes the players accumulate Edge Dice that they then bring to bear in the final scene, the actual duel. The duel is played out in a single scene and the winner is determined by the die roll. Jim McClure took “A Single Moment” and reworked the game into Reflections. In his remaking the game, he extended the flashbacks to focus on five specific moments that the friendship becomes unraveled (The Time We Were Friends, The Time You Crossed the Line, The Time You Failed Me, The Time We Strived for Peace, and The Time It Came to Blood). To create drama and surprise in the scenes—and as a way to give players a reason to make the decisions they make during play—McClure created hidden agendas for each player in the scene, a secret thing they are pushing for or tying to achieve during play. Success in those goals resulted in more dice for the final confrontation. While the game itself still focuses specifically on samurai, there are proposed expansions at the back of the book for using the game to play gunslingers, or battling pirates. Till the Last Gasp is designed for any dueling pair: wizards, psionics, supers, gunslingers, pirates, samurai, robots, whatever! The dueling pair does not have any set past, so they can be long-time enemies, fallen friends, ex-lovers—whatever you want. Also unlike the preceding dueling games, Hindmarch chooses to focus on the duel itself, rather than on the backstory. But that doesn’t mean that this is a strategic or technical game. It is above all a game that creates a story even as it asks you to focus on the fictional actions of the characters right here and now. The game begins by establishing your characters, where they are, and why they have come to this place where only a duel can resolve their issues. The box comes with a number of pre-made characters and locations, and the instruction booklet includes a couple of pre-designed situations to get you moving quickly if that’s the way you want to play. All characters need are five things: what they are known as (their name or title), what they are notorious for (their reputation, true or not), what they are recognized by (key facets of their dress, physical appearance, or demeanor), what their overt motivation is (why they claim they are involved in this duel), and what their hidden motivation is (what really drives this feud, whether the character themself recognizes it or not). The booklet lists 20 options for each of these facets allowing you to either roll them up or to be inspired to create your own characters. Notice that there are no statistics or anything other than fictional positioning required for characters. That means that this game can be ported into your other RPGs if you desire. You can bring your characters from another game to play out their duel in a meaningful way. Next, you have to establish the stakes of the duel. Are you fighting “To the Defeat” (one character loses the rules of the duel), “To the Exile” (the loser of the duel is banished), “To the Turn” (the winning character convinces the losing character to join them in their cause) or “Till the Last Gasp” (the loser of the duel also loses their life). At any point in the duel, the players can agree to escalate the stakes up the chain. Or, any player individually can choose to deescalate the stakes. It’s a lovely safety tool built into the game’s design. The last thing selected before play begins is an Objective card for each player. Each card lists 4 objectives that that player will want to complete during the battle. Some objectives will take multiple actions (like landing 3 hits on your opponent), and some can be done in a single turn (like escalating the stakes of the duel). Each player is dealt 3 Objective cards and selects one for this duel. The duel itself takes place in 4-6 rounds. Each player has 10 Edge Dice (d6s) and a Duel Die (d20). At the beginning of play, they “ready” 5 of the Edge Dice, but putting them in the Offensive pool or Defensive pool. At the start of each round, the players do two things. First, they select their starting stance and they select how many dice they want to roll to determine how many actions they get to perform this round. Each player has a set of Stance cards. The player can be Bold (playing offensively), Wary (playing defensively), or Quick (playing between Bold and Wary). Each stance gives the player access to a set of actions. Each action costs a number of action points to perform. Striking your opponent might cost two action points. Changing your stance to a different stance will cost two or three action points depending on what stance you are currently in. The setting cards consist of four locations, and some of the locations give you access to location-specific actions too. You can move to another part of the setting or destroy part of the setting using action points. The dice you roll will determine how many action points you have to spend. In the round. You each take turns spending action points and narrating part of the duel. When you are out of action points, you can roleplay your character, but you can’t take meaningful actions like those stated above. Then when both players are out of action points, you go to the next round, select your starting stance, and roll your dice pool to determine how many action points you have for the new round. Note that you can only “ready” new dice by using an action to do so, so your die pools will naturally dwindle during the game, giving you fewer and fewer options, making each round brisker and more deadly as you spiral to the finish. Once you have played to at least the 4th round, and once you have accomplished at least 3 of your 4 objectives, then you gain access to the “End the Duel Decisively” action. The first player to reach these goalposts and pay the action points to take the action gets to narrate how the battle resolves according the current stakes. That player can certainly narrate their character winning, or they might find it more fitting to have their character lose. The last element of the game is the Drama Cards. This is a deck of cards with narrative prompts. They tell you to reveal what your character is thinking or remembering. They prompt your character to taunt or plea with their rival. Sometimes the cards will make you or your opponent change their stance, gain or lose action points, or affect the other mechanisms of the game. My son and I played the game last night and had a wonderful time. The box says that the game goes for 60-90 minutes, but it probably took us 2 hours to play from the opening of the box to the end of our duel. Future games will likely take less time now that we are familiar with the rules. We used the included pre-made characters and selected the Aztec Arena as our setting, making our story something of a sci-fi wrestling match between an established talent and the rising star. The mechanisms of play all interlock smoothly together to make play exciting, surprising, and easy to play. Objectives give you reasons to do things and make decisions. We moved around the setting not only because it was good for the story, but because it allowed one of us to mark off an objective. We changed our own stances and our opponent’s stances because it was flavorful and because we could mark off an objective. Even when my son forced me into a rattled stance to keep me from being able to replenish my Edge Die, it was fun for both of us. I didn’t feel like they were keeping me from playing as you could feel one character keeping the other character on their back feet. It had the elements of tactical play without ever making anyone feel like they needed a strong tactical position to play and enjoy themself. And the Drama Cards did their part beautifully. Some actions let you draw a drama card, some force your opponent to draw a card, and some make you both draw cards. The cards act both as wild cards (will they affect the game state?!) and as much-needed role-playing prompts that let us indulge in character and backstory. Players can choose exactly when and where they want the Drama cards to get used in play which allows them to steer those moments. And the cards prompts (at least the ones that we saw) were never daunting. They didn’t demand us create too much backstory or character at any one time. No one had to sit thinking for a while to answer a prompt, so the momentum was never injured by these draws, only ever enhanced. The result of everything working together was a visual tale full of character and conflict that arced nicely from beginning to end. It had been a while since I was able to partake in an RP experience, and it was lovely to get to play with my son and laugh and ooh and ahh at their character and decisions. Till the Last Gasp is a cleverly designed game that scratches several different gaming itches. If it sounds like your kind of thing, you should give it a try!

1 Comment

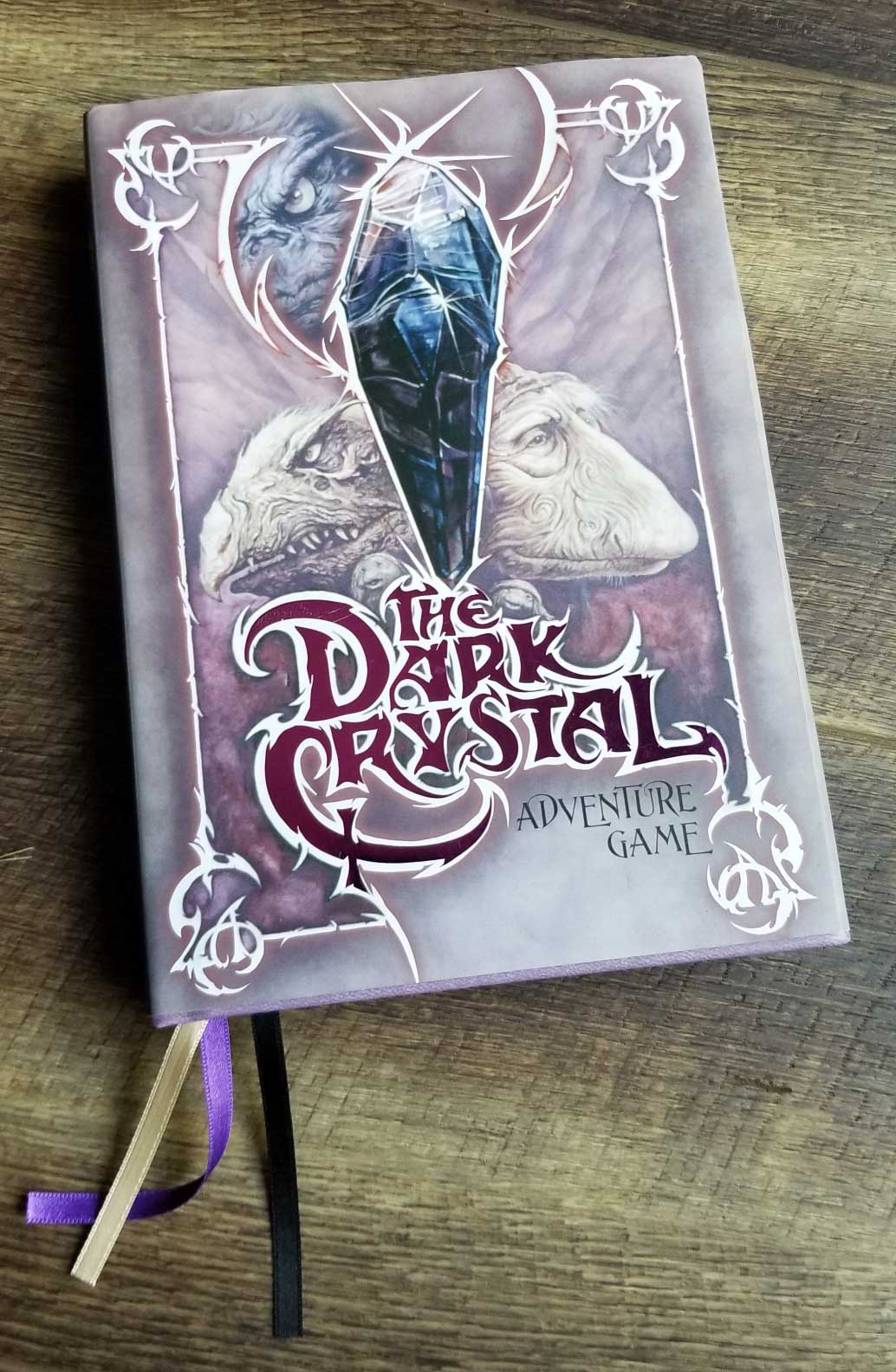

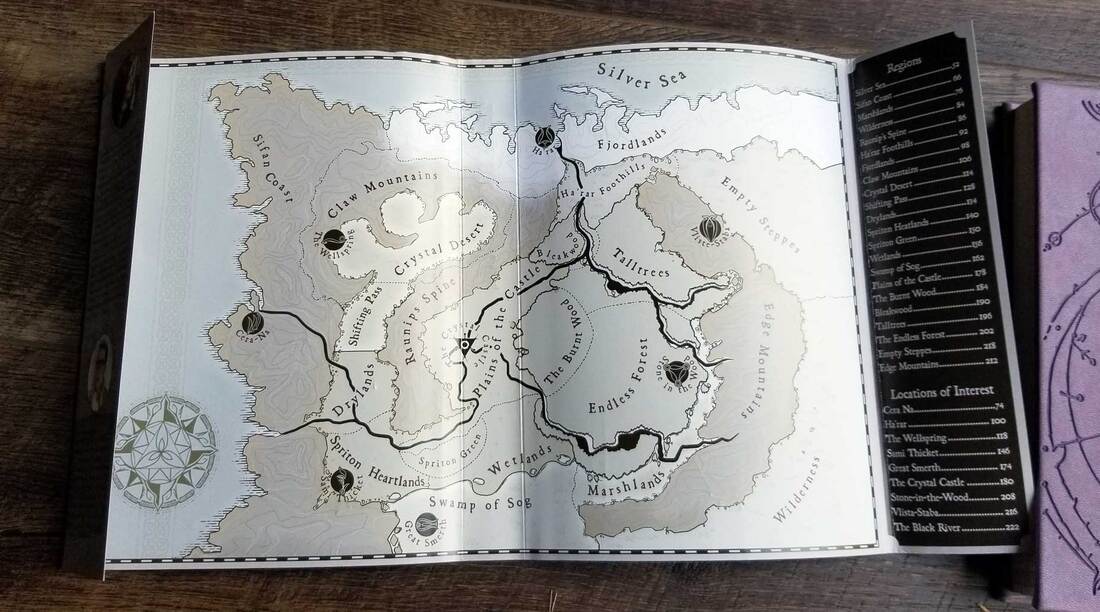

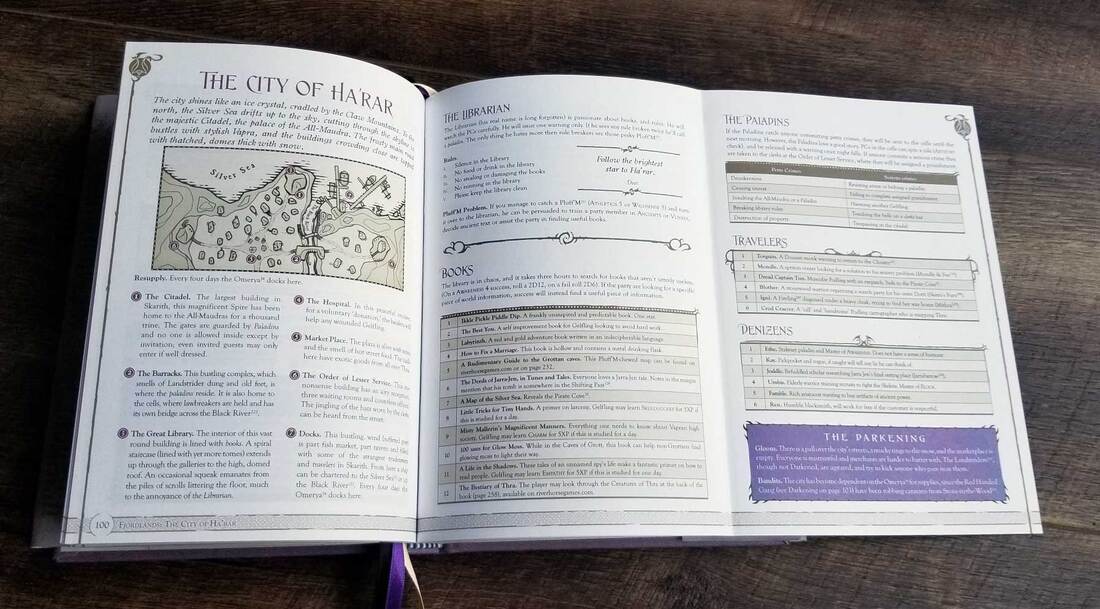

I picked up this book at a local game store for a handful of reasons. First, I was looking to buy something –that’s no small thing in itself. Second, the book itself is very beautiful—it has a lovely color palette, is full of maps and tables and art, has pages that fold out, and even has a few vellum pages that allow the maps to layer. Third, my wife has a long-lived love of the original movie, and I was looking for something the two of us could play one-on-one in short bursts over the summer. Because of all those beautiful features, the book is not cheap, coming in at about $45 for a 300-page, hardbound, digest-sized book. Actually, the quality is not the sole cause of the high cost—there is a lot of game material in this book, a whole world created and parceled out to be the focus of high adventure. You get a lot for your money here, and for that reason, the book is reasonably priced. The game itself is related to a lot of OSR-type RPGs. You have an adventuring party; you use a full set of polyhedral dice; play roles are divided between a GM and players; your characters are defined by their skills, strengths, and weaknesses; your characters track their health and suffer consequences when their health is low; your character has traits that help them achieve tasks or allow them to do things they otherwise couldn’t do; your character’s equipment matters and is limited by the rules of the game; your character has a particular cultural background that informs what they know and what they can do; there is an experience system by which your characters improve over time to be more powerful, more efficient, and more effective; you roll dice when your character attempts to do something with an uncertain outcome, with the roll determining success or failure. Play itself is a matter of the GM setting the scene, players saying what their characters do in response, and the GM having the world respond to those reactions in kind. Gelflings are fragile creatures, and some of the encounters are dangerous, so the facts of the game encourages players to play cautiously to protect their characters, even as those same characters are heroes, set up to save all of Thra from The Darkening. At its root, The Dark Crystal Adventure Game is a game of exploration. While players are expected to be familiar with the world through the original movie and, more pertinently, the Netflix limited series The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance (the same time period in which the game is set), the specifics of the world and the regions explored are necessarily a mystery to the players. The map of the world takes into consideration maps that have come before, but the geography is entirely new. Moreover, the quest presented to the players depends on the players not knowing exactly where to go. The players are given a map of the world, divided into 22 regions, with only major cities and areas marked. Your character may have bits of information about the world depending on what type of Gelfling they are, but that information is only general. This design decision, I assume, is so that the players can experience the same sense of surprise and wonder at Jim Henson’s world even when they are playing inhabitants of that world. The mechanics are stripped down and rather straightforward, using a lot of techniques developed by indie designers. For example, the damage rules are elegant and simple. All health is given a die size for its rating. Gelflings all have a d6 health. When you take a wound, you reduce your die size by one. So a single wound brings a Gelfling to a d4. If you take a wound at d4, then you roll a d12 on a random injury table to find out your fate, which ranges from getting a scar to losing a limb to death. Combat is less exciting, consisting of a series of rolls to determine if you hit or if you dodge a blow. The GM does not roll, but the player does roll separately for attack and defense. So the first round you try to wound your opponent and the following round you try to avoid a wound yourself. The one little spice to the combat system is that fighters are trained in either finesse or ferocity, attacking with brute strength or dexterous sword play. The cool thing about that is that some creatures can only be wounded by finesse because their armored shells can withstand brute force, while others can resist finesse but suffer against ferocity. As a result, you’re not ever just good at killing all things. Whether your battling or trying to overcome an obstacle, everything is a Test, in the language of the game, with a target number determined by the GM. Your skill or ability determines what size dice you roll to accomplish the goal. There is also an advantage and disadvantage system, like so many games now, that allows you to roll two dice and take the higher roll or force you to roll two dice and take the lowest roll. In short, the mechanics work and are well designed but not especially noteworthy. There is little in the game that requires you to use these particular mechanics and you could just as easily use whatever system you want to play within the world presented in the rest of the book. The bulk of the book, a full 200 pages, are used for the included adventure. That’s a funny way to put it because it is itself designed to be a single adventure, though you can certainly use the content in whatever way you choose. The basic setup is that all the player’s characters have come to the Mystic Valley for one reason or another, where they are informed that in order to save Thra from The Darkening, they must gather up a seed from each of the seven great trees and return them to the Mystic Valley within the next 99 days, or a great calamity will befall Thra. Then the characters are let loose to wander Thra, find the trees, collect the seeds, and return as the days tick on. The designers can’t expect you to commit to memory all the ins and outs of the entire world, so they designed the book to be easy to reference and work with on the fly. Each location in the world, be it a full region or a single encampment is given a two-page spread, clearly labeled and easy to navigate. If too much information is required for the spread, the pages will fold out to give you the extra space needed without ever breaking the two-page layout for what follows and precedes. The locations are essentially nested within each other to make moving from one place to another easy. What I mean by that is that each region is given a two-page spread. The 6-8 locations of interest within a region follow that two page spread, and if there is sub-locations within those, they follow the location they are subordinate to. So, for example, there is a spread for the Silver Sea, that tells me what the 6 locations within that region are. I also get a random encounter to use within the Silver Sea while characters are traveling from one location to another. Then each of those locations are presented as 6 separate two-page spreads that follow the Silver Sea spread. So when the characters to the Dreaming Isles, I go to that spread and have everything I need for that part of the adventure there. And when they leave the Dreaming Isle, I turn back to the Silver Sea spread for everything I need until they arrive at their next location within the Silver Sea Region. When they leave the region, I just turn to the neighboring region and repeat the process. If you’ve given a cursory read through the book, then all that should be required to orient yourself is two minutes of skimming. Obviously what is presented in so small a spread are just the bare bones. You get the names and motivations of any anticipated NPCs and the details of any special items. Then it is up to you to make that part of the adventure as detailed or as high-level as you want. You can quickly talk your way through an encounter to get to the next location, or you can slow down and role play the entire conversation, bringing the NPCs to full life. You can have a whole session take place in a small market or fly through a whole region in a couple of sentences. The designers had fun connecting characters and regions and events so that the NPC you meet here has ties to a family in this other region over here. The wandering creature you can encounter here belongs to this shepherd who is looking obsessively for them over here. You can play it as randomly as you liked, using the tables either for inspiration or strictly by the die roll to see how the world comes into focus over time. Reading through the spreads you get a full sense of the world and all the connections holding the place together, making it dimensional and alive. Even just as a read it’s a fun experience.

And now for the coolest part of the game. Remember those 99 days that the players have to complete their mission. You, the GM, actually have a calendar by which you track those 99 days. You can play out the passage of time through reason, but each region lets you know how many days it takes to cross the region, so simply moving will push that clock forward. Dotted on the calendar are days marked in purple, and when you reach one of those days, you choose a region to experience The Darkening. At the beginning of the game, only the Plains of the Castle, where the Crystal Castle sits, are Darkened. And as the purple days are reached, the Darkening spreads to a neighboring region, which you can choose or decide randomly. Each location spread includes a purple box that tell you how the region is changed when it’s Darkened. Typically, creatures become more ferocious and NPCs become ruder, more selfish, and even violent. Weather can get severe and crops can fail. To me, that’s an exciting feature, because even reading through the spreads, you have no idea what the region will be like when the players’ characters finally get there. And the more time passes, the more trouble they will encounter. It’s a game-wide clock that adds life and excitement to the whole setup, in my eyes. And the design of the calendar is cool, as they made the sheet into a GM note page, where you mark what NPCs have been encountered, what regions have been Darkened, and any notes about things you want to remember to bring back later in the game. I mentioned earlier that the game has a built-in experience system. The system itself is unremarkable, but one aspect about it I do enjoy. Each skill a character can have has three levels of mastery: trained, specialization, mastery. The only way to attain that last rank, mastery, is to spend XP to have an NPC train you. So players are encouraged to save their XP and talk to NPCs to find out whom they can learn from. When they meet the right person and have the XP available to them, then they can train with them in the fiction and attain the mastery rank. It’s a minor feature of the game, but I think it’s cool. Originally, I planned on using the rules as written to run the game with my wife, but I’m tending away from that now, primarily because the test system really only cares about success and failures. That’s never a design that excites me, but it can be especially disastrous with one-on-one play. For an example from the adventure, there is some random encounter that has the characters come across a trap and fall into a pit if they don’t roll some target number. With 4 or 5 characters, one of them is likely to succeed in the roll and then they can work to get their friends out. With one character, if you whiff, you are then stuck in a pit until some NPC character comes along to help you out or until you roll a successful roll of some sort to escape. The latter is unexciting. The former is predictable. Neither makes for a fun session. I put off writing this review because I was hoping to put in a number of sessions before I did so. Life has intervened with my play plans, so I’m writing this now before I forget the system. I might write a follow-up when I finally get to play. Even without playing, the reading and the journey in my own mind was enjoyable enough to cover the cost of admission, for me. If this is up your alley, it’s probably worth checking out. Alas for the Awful Sea marks Hayley Gordon’s and Vee Hendro’s entrance into indie TTRPG publishing. The game was Kickstarted in 2016 and saw print in 2017. While it does not use the powered by the apocalypse branding, it does use “The Apocalypse World Engine,” as credited on the copyright page. In fact, the game hews pretty closely to Apocalypse World in moves and play, not especially surprising for a freshman effort by designers. The real and lasting draw to Alas for the Awful Sea, for me at least, is the setting. Players take on characters who crew a ship through the British Isles sometime in the mid-19th century. The weather is cruel, the sea is dangerous, and the people and times are equally hard. In preparation for the game, the GM creates a town with two or more groups in conflict with a number of “currents”—“connected and interwoven problems and situations, exploring one centra conflict.” The GM is encouraged to tie the PCs into the town by creating connections, and then the PCs interact with those conflicts and currents as they see fit. In classic Apocalypse World fashion, GMs are encouraged have a set of backstories and concerns, but no plot, playing to find out what the PCs make of the difficult situations presented them. Over the course of the game, PCs visit various towns as the world of that group is slowly fleshed out. The advancement system is designed to anchor the characters to the developing world, to call on previously gained knowledge and previously encountered NPCs. The setting is thoughtfully reduced to six bullet points to guide the GM:

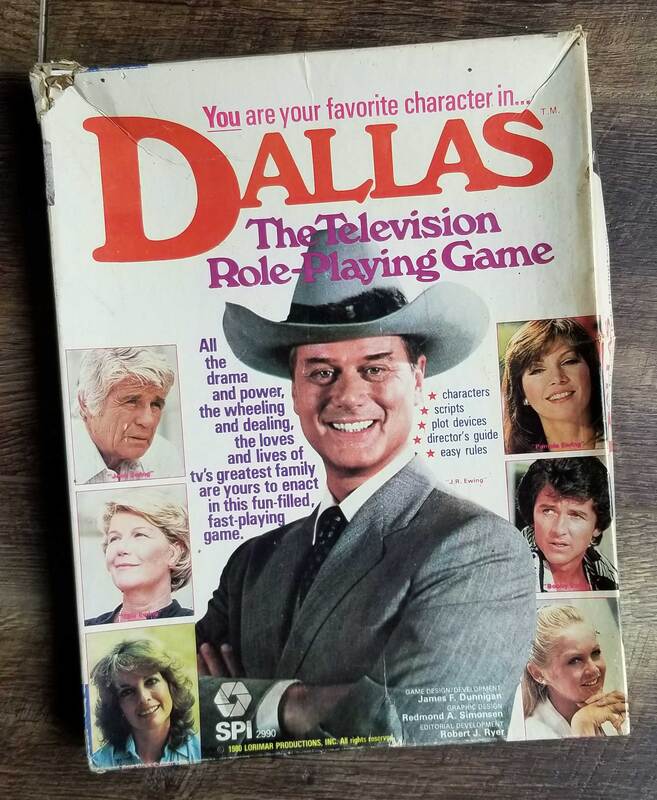

Each one of those points is expanded upon following a short introductory chapter. It’s a powerful description of the world, and as I said earlier, one of the most compelling parts of the book. Between that section and the later chapters on folklore and the history of the times, Gordon and Hendro do an admirable job bringing the world to life quickly and easily. You do not need to be a historian to understand the troubles and challenges of this world. You are encouraged to take this historical setting and fictionalize it, a job made easier, by the encouragement to bring regional folklore into your game, not as colorful background, but as present reality. For the most part, the presence of selkies and ghosts is the job of the GM, but the mechanics do make it all tangible for the players through the game’s version of Apocalypse World’s psychic maelstrom: the beyond. PCs can use the move “sense the beyond” to apprehend the other worldly mysteries GM’s are prompted to include in their scenario. It would be nice to see the folkloric aspects integrated more fully with the rules and procedures of the game, but there’s nothing lost by setting all that on the GM’s shoulders. The chapter on folklore is just a collection of creatures, spirits, and places that you can bring into your games. As has been popular in a few other games inspired by Apocalypse World, the PC character sheet has two halves to it. Each player picks a position on the ship (captain, boatswain, sea dog, stowaway, etc.) as well as a “descriptor,” a narrative background or impulse that defines the character (the lover, the kinsman, the believer, the creature, etc.). These two selections give you your special moves and a set of prompts for creating the relevant details for engaged play. The moves are competently made, but there is nothing in here to surprise or advance the art. Where I think the game does do something innovative and interesting with regard to the PCs is the advancement table. An advancement is given for each PC at the end of each “tale.” At that point, they get a pre-determined advancement (such as an improved basic move, a familiarity, or new bonds with other characters), and one of their choice, including the option to create a new move for that character. The list shows that the designers had a clear understanding of what they wanted to accomplish through advancement and how they wanted play to develop over time. Each option makes the previous tale mean something going forward. Your character learned something knew, met someone important, improved in a skill, or changed significantly in some way. As a result, future tales will involve reaching back to the experiences that have come before in order to be more effective going forward. Importantly, improving stats is not an option in advancement. This is not a game where the characters will become smarter or stronger. It’s one in which they will learn and grow. The other aspect that I think is will done is the half-page GM sheet, and specifically, the list for “Making Things Worse.” Instead of telling players to “be prepared for the worst” as the Bakers do in Apocalypse World, Gordon and Hendro tell players that “The GM makes things worse,” a phrasing that I did not think improved upon the original. However, they broke down GM moves for making things worse in an interesting and productive way, noting that the GM can “complicate the moment,” “change relationships,” or “complicate the future”: Complicate the moment That’s a clean and useful guide for thinking about ways to, indeed, make things worse. It shows a clarity and vision that we see develop and grow further in the games that Gordon and Hendro go on to make after Alas. The book comes with a pre-made tale in the final section of the book. This tale, which shares its title with the title of the game itself, makes it clear that Gordon and Hendro have a talent for creating scenarios, but it also shows that the GM tools provided with the game are limited and will need creative expansion by the GM to be fully playable. As I mentioned earlier, GM prep involves creating a town and a number of “currents.” There are sheets to aid the GM in creating them, as well as a list of appropriate conflicts to sit at the heart of all these troubles. Interestingly, we are never given the town or currents sheets for the included tale. Instead, we are presented the tale much as you would find in a purchased module for any number of other games. We are presented narratively what the PCs will encounter and how NPCs will react to them. We can deduce the various conflicts, but they are never named. We can piece together what the currents might be, but they are never laid out for us. That’s because, I’d argue, the town and current sheets are merely organizational tools, and incomplete ones at that. The reason I call them incomplete is that the final tale of the game does much more than you are ever prompted to in the worksheets. Namely, you have to create a relationship map. The reason Alas for the Awful Sea works so well as a tale is because all the characters and relationships cross the various conflicts and concerns. Relationship maps were first introduced in Ron Edwards’s Sorcerer supplement Sorcerer & Soul. In it, he proposed that open-ended scenarios could be created by structuring not a plot, but a background story full of characters needs, wants, and baggage. That is precisely what Gordon and Hendro put together here. I anticipated running the scenario for a friend I’ll be introducing to roleplaying soon, and to get a better grip on the tale, I turned it into a relationship map, and everything ties beautifully together. Ideally, the GM tools of the game would give you guidance if not tools for tying the various threads together via a web of relationships. What we are given is certainly workable, but it reminds me of that joke about the old instruction for drawing an owl, in which you first draw a circle and an oval; then a couple of lines for the shapes of the wings, legs, and eyes; and then in the final step you are told to draw in all the details that make this collection of lines into an owl, the caption of which in the joke is, “draw the fucking owl.” It is probably too much to ask first-time designers to create such tools, but without an innate understanding of them, GMs will most like just draw their adventures from the published tales or work through trial and error to see what works. I haven’t got to play the game yet, but I’m hoping to soon. I’ll start with the included tale, and if it goes well, I’ll venture into creating a town and currents for myself and see what it takes to go well. While there is nothing to amaze in this short volume, there are a few treasures that make it worth the reading, assuming you are already interested in its basic offering. Here’s how the SAGA rules work in the Marvel Super Heroes Adventure Game, first published by TSR in 1998. The system was first used in TSR’s 1996 DragonLance Fifth Age, but Mike Selinker made some significant changes to the system from the second game. I’ll be pointing out differences as I go. If you’re interested in a thorough explanation of the system as it appears in the DragonLance game, check out my related post. The heart of the system is still the Fate Deck. The deck has 4 main suits, each corresponding with a character statistic. The green suit aligns with Strength, the red suit aligns in Agility, the blue suit aligns with Intelligence, and the purple suit aligns with Willpower. Each of those 4 suits has 20 cards, with their values spread out in a bell curve. In each of these main suits, there is one 1; one 2; two 3s; four each of 4, 5, and 6; two 7s, one 8, and one 9. The average draw, then, will be a 5, and over half the draws will be a value of 4, 5, or 6. This curve removes some of the swinginess of the DragonLance’s Fate Deck, which has 8 main suits of 9 cards each, valued 1 through 9. Moreover, the deck (and game) is simplified by cutting the number of stats (and therefore suits) in half. Now, instead of having one suit for acting and a different but related suit for reacting, you just have the one suit no matter how you are using that stat. Whether you’re using your agility to move swiftly through a crowd or dodge an exploding arrow, you just need the one stat. And just has the DragonLance Fate Deck has a ninth suit, the Marvel Fate Deck has a fifth suit, the Doom suit. This last suit has only 16 cards: one 1, one 2, two each of 3 through 8, one 9, and one 10. The average draw will still be a 5, but the Doom suit has more built-in swing to it, and it allows of course for the only 10 in the deck. During play, each player of a Marvel hero has a hand of cards drawn from the Fate Deck. The hand size will be between 2 and 6 cards, depending on the character’s “edge.” Edge is the game’s way of measuring experience and resourcefulness of a character. Captain America and Dr. Doom both have the highest edge available, whereas new and inexperienced heroes will have lower edges and fewer cards in their hand to choose from. When your character goes to perform an action which might fail and might lead to trouble, the GM will determine what stat is being drawn upon to complete the action. A character’s stats range from 0 (inordinately weak) to 30 (cosmically strong). 3-4 is the average human’s stat, with 7-8 being professional levels of natural and learned abilities, 10 being the maximum unaltered human potential, and 12 indicating the maximum enhanced human potential. As you can tell from that, the number indicate an exponential curve rather than a flat one. Once the stat is determined, the GM decides the level of difficulty for the action. Difficulty levels also curve exponentially, represented by numbers in increments of 4, maxing out at 40. An easy task is rated at 4. An average task is 8. A daunting task is 16. A superhuman task is 24. A godlike task is 36. An impossible task is 40. With the stat and the difficulty determined, the player can then play a single card from their hand and add the value of the card played to the score of their appropriate ability. If that total matches or exceeds the difficulty number, then the character achieves success. If that total fall short of the difficulty number, then the character fails to meet their objective. So, if Captain America, with a strength of 10, uses his strength to, say, lift something or punch someone into next week, the player can add one card to it with a value of 10 maximum, bringing the total to 20. So how does Captain America achieve a task that is “superhuman”? There are two ways to increase your total for incredible achievements. The first is the use of trump cards. A trump card is any card whose suit matches the suit of the action. So if Captain America is using his strength, and the player plays a Strength card, that is considered trump. When trump is played, then the player gets the value not only of the trump card played, but additionally, they get to flip over the top card of the Fate Deck and add the value of that extra card to their total. Better yet, if that flipped card is also trump, then they get to do it again, and to continue to do it until a non-trump card is flipped. This allows for critical successes. The other way to play extra cards is tied to the character’s edge score. Edge scores range between 0 and 4. I said before that Captain America has the maximum edge score, so he has an edge of 4. Players can play cards whose values are equal to or less than the character’s edge score for free before playing their one main card. So if Captain America has two 3s, a 5 and an 8, then the player can play both 3s before playing the 8, giving Captain America 14 to add to his strength score of 10. And if that 8 is trump, then on average he’ll flip over a 5 taking his total to 29 (or whatever the actual value of the card is). From that, you can see how edge measures a characters resourcefulness and experience. It not only gives them more cards to choose from—which means they have a greater chance of having cards in trump for any given action—but it lets them make better and more use of their smaller cards. A character with an edge of 1, only has a hand of 3 cards and can only play 1s for free when performing an action. Every action in the game is tied to this same system. Powers are given “intensity” ratings, which are exactly like ability scores, and each power is given a suit so trump remains consistent for them. When an action is opposed, things get even tougher. It is an easy task (so, a 4) for Cyclops to shoot his optic blast at a villain, but the villain gets to add their score to the target number if their doing any thing other than taking the blast. So if Sabertooth is dodging Scott’s blast, then the GM add’s Sabertooth’s Agility score of 10 to that easy’s 4, bringing the total up to 14. In fact, it’s harder than that. The Fate Deck isn’t just for players to draw from. The design of the game hooks the Fate Deck into most mechanically significant exchanges. I’ll explain how in just a moment, but first let’s touch a little upon the SAGA system design philosophy. When William Connors designed the system for DragonLance, the idea was to center the mechanics on the heroes of the story. As such, all actions were structured from the PC’s perspective. To this end, the GM never drew a card when an NPC attacked one of the PCs. Instead, the NPC’s success or failure was determined by the PC’s reaction. That same philosophy is carried over into Mike Selinker’s iteration of the ruleset. When Sabertooth claws at Captain America, the success of that attack is determined not by the actions of the NPC or the GM, but by the reaction of Captain America. Captain America would make an easy resistance using his agility to dodge the attack, but Sabertooth’s strength of 10 would of course be added to that difficulty. If Captain America’s player has the cards to successfully dodge Sabertooth’s attack, then Sabertooth misses altogether. If Captain America’s player doesn’t have the cards, then those claws hit their mark. We can talk about damage soon enough, but let’s first look at all the other ways the Fate Deck is used in play, especially by the GM. First, each card has an “aura,” either a positive, negative, or neutral value. This variation is spread evenly throughout the 96 cards, so there is a 1 in 3 chance of drawing any particular aura. The GM can use this to answer questions that they want to declaim responsibility for but for which there still needs to be an answer. What’s the weather like? Do I happen to hear what they said? Does the bridge hold up under all this weight? The GM can flip a card and see if things are favorable, unfavorable, or neutral for our heroes. Second, when players play cards from the Doom suit, the GM pulls those cards out of the discard pile and places those cards in front of them. At any time, the GM can use those Doom cards to increase any one difficulty score by that much, giving the GM a pacing mechanism for building up to important and difficult climactic moments. When a player makes use of that 10 of Doom card, the players all know that it can come back to bite them in the ass later. Third, and finally, the GM makes use of the Fate Deck during combat scenes. The combat scene is the heart of any given game of Marvel Super Heroes Adventure Game. Having read several published adventures, I can tell you that they are set up with scenes of combat at all the turning points. At the start of each round of combat, called an “exchange,” the GM flips over the top card of the Fate Deck and lays it face up on the table. First the GM reads the aura. If it’s positive, the heroes get a second wind and heal up before blows are exchanged. If it’s negative, then the villains get a second wind and heal up instead. A neutral aura has no effect. Next, the GM is invited to create an “event” inspired by the card. Each of the 96 cards has the unique picture and name of one of the characters from the Marvel Universe, and each card has a unique phrase, appropriately called an “event.” Some example event phrases are “Personal Tragedy,” “Rescue, “Out of Control,” “Rookie Mistake,” “Explosion.” The GM can use this event phrase to introduce a new element to the exchange, complicating or changing the focus of the battle. Or alternatively, the GM can introduce the character pictured on the card into the scene, bringing in a new villain or another hero. It’s a neat way to keep battles from become stale exchanges of powerful strikes until someone passes out. And better yet, each event phrase is tied to a particular “calling,” which is part of each character sheet. Every character has a central calling, a reason they suit up and go out to fight the bad guys. Captain America is an “idealist,” The Human Torch is a “gloryhound,” Spiderman has “responsibility of power,” and Mr. Fantastic is an “explorer,” just to name a few. When an event matches a hero’s calling, then the hero must address that event, because it speaks to their very purpose for being here. Anchoring events to callings is a clever reminder to the GM to hook these things directly into the interests of the character, and therefore, presumably, into the interests of the player who chose to play that character. This summary of the mechanics has already taken up way more space than I would have liked, but let’s finish it out and talk about harm. Heroes do not have hit points or any such equivalence in this game. In fact, except for abilities, edges, handsizes, and intensities, everything on the character sheet takes the form of words, not numbers. So when a hero gets haymakered by a villain, you don’t have to write anything down. Instead, after you calculate the damage of a blow taken, you discard cards equivalent to or greater than that damage. So if Captain America fails to dodge that swipe by Sabretooth and ends up taking 8 points of damage, the player needs to discard cards from their hand that total up to 8. Normally new cards are drawn from the Fate Deck immediately after the old ones are played. Injuries however change that. If they have an 8, they can throw that one card, and their handsize is reduced by that one card until the fight is over. Or they can throw a 3, a 4, and a 1, and reduce their handsize by three cards until the fight is over. Or, lets say, the player has two 5s, three 6s and a 7, then the player is forced to discard two cards to meet the 8 minimum. In this way, the player’s handsize gets whittled away through combat, depleting their resources and options until they have to discard their last hand and pass out from exertion or their wounds. Again, you can see how starting with a handsize of 3 (which means an edge of 1) limits a characters ability to hang in through a battle. Whew! We got through the summary, hopefully in such a way that you can imagine play. There’s a lot here that I like. If you read my review of DragonLance Fifth Age, you’ll get my general thoughts on the design and focus of the system. Instead, I want to talk here about a couple features of the design that I didn’t get to touch on before. How does having a hand of cards affect play? That’s an important question and one that has occupied a good bit of my thinking lately. Please note that what follows are mere speculation since I have not been able to convince anybody to play a session or more of the game. There are several things that I think would be cool about having a hand of cards to look at while we play. The first and most obvious is that I can look at my hand and see exactly how my hero is feeling at this moment. If I have a fist full of strength cards, I know what kinds of actions I’m going to be successful at. If I have a fist full of low cards, I know that I’m going to start out relatively weak and hope to draw into better cards. If I have a number of high cards, I’ll know that I can start trouble and write checks that won’t bounce, as it were. In fact, the cards allow me to engage in a little play strategy. I might take on low-risk stunts to use the low-value cards from my hand safely in an effort to get bigger and better cards of the right suits before trouble comes looking for me. And I really love the notion of watching your hand size shrink before your eyes as the battle progresses. You can visually trace your limitations, needing to martial and deploy your resources carefully as the battle draws to a close. On the other hand, I can see some negative impacts during play. When I’m roleplaying using dice, I might play around with the dice, but I’m not necessarily focused on doing something to roll them. When it comes time to roll the dice, I’ll gladly do so, but I’m happy to take my time getting there. I imagine the pressure and desire to use the cards in your hand is acutely stronger because you are looking at specific resources just begging to be used and exchanged for different one. This naturally encourages us to move through the roleplaying as quickly as possible to get to the fight. There’s nothing innately wrong with that, of course, and in fact, this game is wisely set up to have all the mechanics geared toward that same thing. All aspects of roleplaying, of character interaction and expression, are left entirely up to the players and their imaginations. In other words, they are given no mechanical teeth. There are no mechanics for social interactions or any activity that doesn’t involve your abilities or powers. It occurs to me that it is no coincidence that this feature was used for a game in which you are expected to play with established characters in an established universe. We don’t need to learn who Wolverine is as a character. We don’t need to explore the depths of Storm’s character. We are already supposed to know them in order to play them. We can shout out catch phrases and do our best impressions of their swagger and quirks, and then lets get to them being awesome and punchy! The same thing can be said about the DragonLance game too, really. The characters there may be brand new and created by us, but we know the type of people they are: heroes. The gameplay is not designed to discover characters through play, but to express their heroism through play, which is best done through overcoming conflict than through a lot of talking and socializing. Those other elements might be expected, but they are flavor and at the discretion of the players, not enforced by mechanics of play. With all that in mind, it’s not really a negative, as my first sentence of this paragraph says, but a design decision to keep focus on the use of those cards. That pressure to play cards from your hand is part of the design itself, not an unfortunate byproduct, I think. I also give credit to the designers (of both games) for taking advantage of the affordances of their main mechanics. Skills in this Marvel game have an impact by lowering the difficulty score by a single rating (meaning 4 points). Hawkeye’s skill with archery makes shooting an enemy a zero difficulty rather than an easy difficulty (before adding in the villain’s opposing scores, of course). If you are one of the world leaders in a particular skill, then any card you play while using that skill is considered trump. That’s just elegant and clever design. Finally, I want to say how surprised I was to see how closely this game is related to the original Marvel Super Heroes roleplaying game designed by Jeff Grubb in the 80s. It became clear to me at some point in my reading the text that Mike Selinker sees his design as being a modernized take on Grubb’s game, drawing both on the spirit and the mechanics of the game. The tone nods to Grubb’s use of Spiderman and other Marvel characters as specific voices to explain the rules of the game. There is even an appendix for converting your FASERIP characters to this new system. If you don’t buy any of the Roster books, but have the old rosters from the earlier edition, then you have everything you need. Selinker is not bound by anything that has come before, but it is clear that he takes advantage of all the resources Grubb provided. The list of powers is hardly an exact match between games, but it is clear that the one is used as the foundation for the other. Skills are a clear offshoot of Talents from the 80s. In a lot of ways, Selinker saw his game as a second edition of the same game, not just a reinvention of the wheel. I found that endearing and cool. There were several reasons compelling me to pick up a copy of TSR’s 1996 DragonLance Fifth Age game. The original trilogy of novels holds great nostalgic value for me. While I don’t think I ever played any of the D&D modules from the ‘80s, I owned a few and enjoyed reading them. I’m also a sucker for card games and love to see how RPGs utilize cards instead of dice. That this game used a custom deck was all the more intriguing. And finally, I heard great things about the expression of the fate deck in the Marvel version of the system and wanted to be able to compare the two iterations. All these things sent me to ebay to hunt down a reasonably-priced edition of the boxed set. While my excitement was high, my expectations were actually quite low. I am entirely immersed in the indie side of TTRPGs and have been for six years. Neither D&D nor fantasy games call to me these days. I expected to dig through the rules and find a gem or two worth admiring. To that end, I was glad to see that the main rule book is digest-sized and a mere 128 pages. But what I found there surprised and delighted me well beyond my expectations. Many parts of the game’s rules and design read as early iterations of ideas the indie design scene worked on throughout the first decade of this century. First, the GM and their characters don’t engage directly with the mechanisms of play and resolution. If an NPC attacks or acts on a PC, then the game looks to the PC’s reaction to determine the success or failure of that NPC’s action. We see this today in games like Apocalypse World, where the MC doesn’t roll dice, facing all the mechanical interactions toward the players. Apocalypse World does so (in part) to center the PCs as protagonists, putting them in the driver’s seat of the narrative as it unfolds. While DragonLance Fifth Age still positions the GM, literally, as the “Narrator,” giving the Narrator the responsibility of the “plot,” an unfortunate convention that the game does not escape, the designers specifically center the PCs as actors and reactors because they are “heroes,” and regardless of what happens within the narrative, it is their story. To describe the other early inventions at the core of this game, I need to take a moment to explain its central mechanics. At the heart of play is the Fate Deck. The Fate Deck is made up of 8 suits with values 1 through 9, and a ninth suit with values 1 through 10, making the deck of total of 82 cards. Each of the main suits correspond to an “ability” score on the PC character sheet. The ability are split evenly between physical and mental abilities, and then halved again within each of those divisions. So the physical abilities are divided into coordination and physique, and the mental abilities are divided into intellect and essence. Coordination is made up of agility and dexterity, physique is made up of endurance and strength, intellect is made up of reason and perception, and essence is made up of spirit and presence. While each of those 8 abilities can be used as the basis of a character action, they are paired up so as to be active and reactive. For example, if you are making an attack with your sword, you will use your strength; if you are responding to an attack by an enemy wielding a sword, you will use your endurance. Likewise, if you are using you are making a magical attack, you will use your reason; if you are resisting a magical attack, you will use your perception. Each of these abilities will have a starting value of 1 through 10, with 5 considered the human average. Players have a hand of cards at any time, all drawn from the same Fate Deck. The size of their hand is determined by their “reputation,” which represents their experience as heroes. The more experienced the hero, the more resourceful they are. Starting characters often give their players a hand size between 2 and 5 cards. When a player declares that their character is taking an action, and the Narrator says that such an action has the potential for failure, they turn to the cards. First, they determine what suit is appropriate for the action. Climbing a wall might require strength. Moving across a narrow ledge might require agility. Then the Narrator determines a difficulty rating for the action. The difficulties range from easy to impossible, and they move in 4-point increments. So an easy action requires a 4, an average action an 8, a challenging action a 12, all the way up to an impossible action requiring a 24. The player than plays one card from their hand, adds the value of that card to their ability score, and compares that totaled number to the difficulty number. If they meet or exceed the difficulty rating, they succeed in their action. So, if a player’s character has an ability with a score of 8, they can succeed in an average action without playing any card. When an action is opposed, then the difficulty rating is beefed up by the ability score of the thing opposing the action. So let’s say you’re fighting an ogre. Swinging your sword is an easy action, giving it a difficulty rating of 4. But an ogre’s physique ability is 13, so that gets added to the 4, giving you a total of 17 to hit and damage the ogre. If you have a strength of 9, you’d better have an 8, 9, or 10 in your hand to land that blow. And when the ogre swings at you, you can try to dodge his club, which is an easy action, again a 4, which is added to the ogre’s 13, again giving you a target number of 17. Now you look at your agility score (for dodging) and play a card to add to it. The final element to consider in these actions is the suit of the card you played. It the suit of the card matches the ability you are using to make your action, then that suit is considered trump and you get a bonus. In the examples above, if you play a card of the strength suit to hit the ogre, or the agility suit to dodge the ogre, you have played trump. When you play a trump card, you get to flip over the top card of the Fate Deck and add the value of that card to your action’s total. Better yet, if the flipped card is also trump, you can flip the next card as well, and keep doing so until you hit a non-trump card. This method allows characters to achieve seemingly impossible tasks, although the odds are never in their favor. Still, if you have the 9 in your trump suit, you will draw an average of 4.5—let’s just call it a 4, which means that you have 13. If your basic ability is high, you can get just shy of impossible at 24. You may have noticed that I haven’t yet spoken of the ninth suit, the one that doesn’t correspond to an ability score. That suit is the suit of Dragons. It offers more power by going higher than all the other suits, to 10, but it also threatens to harm you. If trump allows for critical successes, then the Dragon suit allows for critical failures, or what the game gently calls a “mishap.” When you fail an action in which you played a card of the Dragon suit, the Narrator is given permission to make your failure particularly painful. Whenever you play a card, you immediately draw a new card, so you won’t run out of cards by taking actions. Bigger hands of cards help by giving you more options and access to greater odds of having a high card or a trump card in the action you’re taking, or to avoid being forced to play a Dragon card when failure looms, which is how hand size represents experience and resourcefulness. To return then to the innovations of the game, now that you understand the basic mechanics, actions are essentially player-facing moves, reminiscent once again of Apocalypse World. The rule book lists a number of common actions, such as breaking down a door, telling a convincing lie, picking a lock, or intimidating someone. When such a thing happens in the fiction, the players can turn to the move, see the typical difficulty, the typical ability used, the opposing ability if there is one, and the common fallout from mishaps. The players are taught by the rulebook how to create their own actions, and adventure-specific actions come with each published adventure, just as an MC for Apocalypse World will create custom moves for locations or certain NPCs. I was stunned by the similarities. Of course, the actions in DragonLance are restrained by the idea that they can only denote success or failure, so actions are inherently less interesting and playful than Apocalypse World moves, which are interested in branching narrative paths that come out of any given move. The other important difference is that Narrator’s are encouraged to keep hidden from the players the specific difficulty rating for the specific action at hand, whereas the targets and results of moves are apparent to all players. This hidden information is intended to spice up gameplay by keeping players on the edge of their seat to know if they put forth enough effort to succeed at their task. That doesn’t particularly appeal to me, but I can easily see how looking at your hand and seeing that you will either succeed or fail before a card is even played can suck the wind out of a moment of resolution. Another cool achievement by the DragonLance designers is doing away with hit points altogether to measure your heroes health. Instead, the designers take advantage of the affordance that the hand of cards provides. When a hero sustains an injury, they must discard from their hand cards that total up to the damage taken. These discarded cards are not redrawn until the character can heal up. When a player has zero cards in their hand, the character is out of commission, passed out, dying, whatever. This makes for interesting choices and a cool kind of death spiral in play. If you need to discard 8 points of cards, and you have, say, 5 cards that are 2, 2, 4, 4, 8, you have a tough decision to make. You can lose the 8, only be down one card, but have a fistful of mediocrity; you can ditch the two fours, keep three cards, one that is good and two that are woefully unimpressive; or you can throw the two twos and a four, be down three cards but have a strong card and a medium card left for the fight ahead. The fewer cards then restrict both your ability to achieve and your ability to resist. This feature reminds me of nothing so much as the dice penalty for injuries you see in Ron Edwards’s Sorcerer. Bad wounds can have long and serious effects. The cards mean that you can also stop keeping track of gold and silver coins. DragonLance is not about delving in dungeons and scrounging for money. It’s about heroics. So instead of a place to count your currency, you have a wealth score that you can use like any other ability when attempting to buy things, like you see in Burning Wheel. All of these achievements are impressive, I think, because they show that the designers knew what they wanted the game to be about and shaped their mechanics and procedures to reinforce that. The pressure to follow traditional design is always strong, but I can imagine it was even more so for a fantasy game, especially one that began its creative life as a D&D module. I could go on and on. I didn’t touch the magic system, which attempts to allow wizards and spiritualists to create extempore spells. I didn’t talk about the elegance and ease of using weapons and armor in combat, keeping the math simple. I didn’t talk about how all this simplicity allows the main rule book to include a 15-page bestiary (on digest-sized pages, remember) that covers just about everything you need. I didn’t talk about the way the cards are used to help the Narrator get quick answers to questions about smaller things that the Narrator wants to declaim responsibility for but that the table still needs to know. It’s not a perfect game by any stretch of the imagination, but it’s a thoughtful game, a well-designed game, a focused game. I picked up Mothership moved entirely by the hype surrounding it. I’m a big fan of the inspirational source material behind the game, and the entry cost is eminently reasonable, even for a printed copy of the zine-sized text. But alas, the game is not for me. As a game coming out of the OSR movement, it’s not badly designed. The rules for skill checks, advantages and disadvantages, panicking and combat all appear to be serviceable. At the same time, they don’t have anything particularly unique to say. Combat has the standard elements: determining surprise, rolling for initiative, having limited actions you can make on your turn, making an opposed roll to hit. It adds on stress and panic, like bringing Call of Cthulhu and D&D together, and the two features are yoked together pretty well, but that’s about the only part of the game that involves horror. There is no particular vision about what horror in space is about, what it is in the larger genre that makes it compelling. There is no reading or interpreting of the genre, just the standard game parts bolted onto one chassis. To me, the most compelling part of the text is the art, which does a wonderful job of setting a tone and presenting a vision more unique than the mechanics of the game illustrate. This version of the game is only half complete, I know that. In fact, the full game is being Kickstarted even now. But where the designer is comfortable leaving holes indicates what the designer feels can be handwaved without affecting the central concerns of the game. If the elements were essential, they would be integrated with the rest of the design. Take money, for example. We are told that “everything in Mothership from fuel to food to weapons and ammunition costs Credits.” This makes it sound like Credits is a central driver and economy of the game. But then the rest is handwaved. You get a list of jobs you can do, adventure seeds, but nothing else is developed, presumably because the eternal hunt for more Credits is an excuse for getting the PCs into trouble and then making them return to trouble session after session. The game borrows the aesthetics of truckers and blue-collar workers in space, but that’s as deep as it goes. It’s window dressing. It happens to be loveable and groovy window dressing, but window dressing all the same. Horror and Sci-Fi genres, individually, are each rich and roomy genres, with space to make observations and declarations about our world and our humanity. Mothership is a missed opportunity. I didn’t know what to expect from Dallas: The Television Role-Playing Game. I had heard some people say that it was more of a board game than a roleplaying game. Others said it had some innovative mechanics and was actually fun to play. Still others just dismissed it as a weird tangent to the hobby, not part of the larger movement of design and play. I found a cheap and battered, but complete, copy on ebay a while back and finally got to read it. I found the design of the game to be surprising and exciting, personally. I was too young to be a fan of the show, so there’s nothing nostalgic in my excitement. I haven’t gotten a chance to play it, and I doubt that I will, but it has given me a lot to think about. First, there are indeed characters you play during the game. The character sheets provide all the relevant stats for 9 major characters of the show. Each character has numbers Power, Persuasion, Coercion, Seduction, Investigation, and Luck. Power and Luck are single numbers representing the character’s ability to exert influence and escape consequences, respectively. The other four stats correspond to the main actions each character can take, and they come with both an offensive and defensive number, measuring their ability to be persuasive, say, and resist persuasion themselves. The character sheets for each character are almost identical, each sheet show all the major characters’ stats on the front of the sheet, and all the rules succinctly stated on the back. The only difference between the sheets is that the character’s specific stats are placed in bold at the top of the sheet, a brief summary of their character and background in the show is given, and the “Personal Victory Conditions” for each of the three scripts included with the game. Let’s talk about those scripts and those “Personal Victory Conditions.” Scripts are equivalent to adventures or modules in other roleplaying games, or variants and situations in board games. Each script gives you a fictional situation for the game, with a specific setup, a list of which major characters are involved, what minor characters and what plot devices will be in play. Each script is like an individual TV episode, with its own beginning, middle, and end. At the start of play, the Director gives a general setup for the fiction of the story. Then, in private, the director gives each player the specific story and goals of their major character. The game then plays out in five or fewer scenes, and at the end, any player who met their personal victory conditions is considered a winner. Personal victory conditions all involve “controlling” a number of assets—those minor characters and plot devices I mentioned earlier. Minor characters, plot devices, and organizational characters (characters with official titles but not individual names—so, an FBI agent, a Texas Railroad Commissioner, and so on) are all printed on individual cards. Plot devices are just names: Ellie’s Letters, Spanish Land Grant, Saddlebag full of Krugerrands, Cowboy-Redskins Football Tickets. These are the MacGuffins characters are fighting over to control. The minor and organization characters come with stats for all the major actions of the game so they can properly assert and resist persuasion, coercion, seduction, and investigation. Some of these cards begin the game on the table face-up, so everyone knows that they are in play; some begin face down, known to some and not to others, driving those players who are not in the know to investigate to find out who these pawns and powers are; and some are brought in by the Director during the game to introduce new developments and tensions. As I indicated, play progresses through scenes. Each scene consists of a number of phases. First, in the Director Phase, the Director gives out information to the group and to individual players, possibly handing out new minor characters or plot devices. This is just an information phase, but that information can easily tilt the landscape of play. The Director also sets up how long the Negotiation Phase, the phase that follows, will be at this time. The Negotiation Phase allows players to talk among themselves and make deals. The players can trade assets (minor characters, organizational characters, and plot devices), form alliances, make plans, and generally agree upon whatever they can. Players are allowed to take other players away from the table in order to make their deals in private. Finally comes the Conflict Phase, in which everyone takes action. You can try to gain control of minor characters by persuading, coercing, or seducing them away from their current allegiance; you can investigate face-down cards to find out what secrets you aren’t in on; you can even attempt to get another major character thrown in jail if it is known that they have committed an illegal act and you have some form or law enforcement under your influence. When the dust settles, the next scene begins with the Director Phase and it starts all over again. At the end of the final scene, you look at what you control and what you need to control to “win” and see how you did. As you can gather from my description, this is a strategic and competitive game. The amount of roleplaying anyone engages in is entirely up to the players involved. It would be easy to play an entire game without once speaking in a character’s voice or building up fictional scenes for your actions. In fact, the one example of play given in the game books shows the players engaging in nothing fictional, focusing entirely on the pieces of play as pieces of play. Nothing in the rules or procedures force roleplaying. But only the focus on achieving your goal might inadvertently stand in your way of actively creating fictional scenes. The rules prohibit the number of actions you can take during the Conflict Phase in order to reflect that what is transpiring is a single scene (or more accurately, I suppose, an act). Your character can only be in one or two places per scene and only affect one character or plot device where they are. So you can easily set up that moment of conflict within the fiction and play it out before rolling the dice to see if you are successful in your act of persuasion or coercion or seduction or investigation. I think it would be quite cool to see that in play. The game immediately put me in mind of Fiasco. Each player has a character driven by their own ambitions and debts, all connected to each other by a web of relationships, fighting over the same limited pool of resources. The plot devices are just “objects” in Fiasco’s language. That Saddlebag full of Krugerrands, for example, could fit into any number of Fiasco playsets. The tone is obviously different, leaning more towards soap than tragicomedy, but the basic idea of play is strikingly similar. Mechanizing the attempts to gain influence over minor characters through persuasion, coercion, and seduction, is a neat idea, and their execution is admirable. Let’s say you are trying to persuade Ralph Bentocher, the senator’s son, to intervene with his father in your interests. You take your offensive persuasion skill (if you’re J.R., that’s 20) and subtract from it your target’s defensive persuasion skill (Ralph, poor soul, only has a 7 to resist), and get a number (in this case, 13). If that number is 0 or 1, you automatically fail. If the number is 12 or higher, you automatically succeed. If that number is between 2 and 11, you roll 2d6 and see if you can roll equal to or less than that number, you succeed. Additionally, your minor characters can work on your behalf, using the same actions, to increase the amount of influence you can exert in any one scene. And you can use your major characters Power score to help give your lackeys a boost in their efforts. So when Ralph talks to his father, the force of J.R.’s name is behind his own roll to persuade. I like it. This is just a side point, but the way the personal victory conditions are described in the various scripts also put me in mind of Fiasco. Here is what J.R. must control at the end of “The Great Claim” script to win: Land Grant The comments give you both flavor and humor, grounding the bits of paper on the table with the fiction of the game. Moreover, it tells you how J.R. thinks and how he manipulates the world. I find their short lists energizing and compelling, making me want to play and engage with the fiction. The game has me thinking about ways to have enjoyable play while major characters have interests pointed directly at each other, where the heart of play is conflict between characters, not in the form or physically battling, but in the form of influence and manipulation. There’s a lot here to feed the mind. If for some reason I was just burning to play a game like a Dallas TV show, I would just create a Fiasco playset, but it would definitely be playing Fiasco in Dallas’s world. There’s one other cool thing I’d like to point to before wrapping up. There is a section in the books that tells you how to create your own character stats, and I think their method is interesting enough to share: In the game, the character Abilities were initially derived through a somewhat abstract process. A character’s Abilities were rendered into six major categories: intelligence, charm, lack of scruples, physical attractiveness, nerve, and power. The ratings were assigned relative to other characters. A 9 is on the high end of the scale, and 1 is the low end, except in the case of power where a character can have zero. Intelligence was evaluated in terms of both intellect and cunning. J.R. was arbitrarily given an 8. In charm, representing the ability to get your own way on the basis of personality, J.R. rated another 8. For lack of scruples, he was assigned another 8 (there are certain things he draws the line at, particularly where his parents are concerned). For nerve, J.R. again rated an 8, as did Pam, Jock, Bobby, and Lucy. For power, J.R. deserved a 9 without question. Two things I want to point to here. The first is that those original stats, the unseen ones, are a perfect breakdown of the descriptors of the characters in the show. To some degree or another, all the characters are intelligent, charming, unscrupulous, attractive, full of nerve, and powerful. To then turn those characteristics into the verbs that are their actions is common enough in roleplaying games, but that step is often left for the players to calculate. You typically determine their stats and use their stats to determine how effective you are at doing a thing. There’s something cool about that happening behind the scenes here. The second thing that I want to draw your attention to is the imbalance of power between characters, which the game embraces without apology. None of the characters have comparable stats. They are not balanced to make sure that Lucy and J.R. have the same chance to do the same things. That’s a bold move, and one RPGs have been wrestling with for a long time. The way Dallas addresses that imbalance is to give each character personal victory conditions in proportion to their character’s ability. Lucy doesn’t need to control nearly as many things as J.R. In fact, some of Lucy’s win-conditions often line up with another character getting what she wants, which means, Lucy can team up with certain characters to each achieve their shared goals. Weaker characters will team up against more powerful characters and alliances will shift as power shifts during the individual games. It’s built to keep play dynamic and interesting. There is no surprise in the fact that I missed this little RPG boxed set when it came out in 1999. I was only an expectant father, and I had missed the Pokemon craze of the 90s entirely. Moreover, the box hung on racks like any other boxed cards sold for CCGs at that time. Nothing on the box tells you that it is an RPG or related to RPGs. I didn’t become aware of the game until earlier this year when someone on the gaming Slack channel I frequent shared pictures and his thoughts. It sounded cool enough to pick up off ebay for $10 and see for myself. The box comes with an instruction booklet, an assortment of Pokemon cards, a d6, checklists of all available Pokemon cards, two tokens for flipping, and a set of counters for tracking wounds. Play is designed to imitate the Pokemon video games, in which a young protagonist is given their first Pokemon by a professor and then they head off across the land to gather more Pokemon and train up their skills. After covering the basic rules, the instruction booklet includes an adventure to walk first-time players and Narrators through the game. The Narrator is the game’s GM. They assume that a parent will play the Narrator to their children and their children’s friends. The designers—who, sadly, are unacknowledged in the booklet—successfully seized on the two things at the heart of the Pokemon video games: exploration and Pokemon combat. The first, exploration, is achieved by the adventure itself, outside of any dictated rules or procedures of the game. The text of the adventure prompts the Narrator to ask questions about the physical world during play. For example, in the first scene, the protagonists go to Professor Oaks lab to get their first Pokemon. The Narrator is told to ask, “The lab is part of a larger building. What does the lab look like?” Also: “There are computers and machines in the lab. What else do you see?” This invitation to the players to partake in the describing and building of the fictional world is a beautiful way to have the children talk about the exciting parts of the world that occupy their imaginations. The players can surprise themselves and each other with their observations, their memories, and their creativity. It leaves room for the adult Narrator to be taught about the world by the enthusiasts in the room (if indeed the parents are not themselves enthusiasts). The adventure itself is impressively long, well beyond the basic opening scene and battle that I expected. The adventure is varied and gives the players different challenges and experiences, and it introduces them to popular characters from the show and game, like Team Rocket, Police Officer Jenny, and Brock. Players catch wild Pokemon, find a rival, and battle a gym master. Pokemon solve non-combat problems. The only disappointment is that Wizards of the Coast never produced the additional sets that were intended to follow this one, with more Pokemon cards and more adventures. Had I had this game when my son was 8, he would have been thrilled to his Poke-loving heart to have played. The combat mechanics are surprisingly elegant, given how complex they could easily become. The price for avoiding that inviting complexity is that you don’t have cool features like Pokemon attack types having special affects on other Pokemon types. But before we look at what’s missing, let’s see what’s here. The Pokemon cards are two-sided. Half of each side is an illustration of the Pokemon. The Pokemon’s Hit Points are in one corner, falling primarily between 7 and 10. Each side shows a different attack move. The attack move has a name, the odds of success, and the amount of damage it does. The odds of success are written as the numbers on a six-sided dice. For example, on one side of one of my Bulbasaurs is a Tackle attack, which succeeds on a 5 or 6, and which deals out 4 Hits. When I declare Bulbasaur is using their Tackle, I roll the d6; on a 1-4, Bulbasaur misses, but on a 5-6, Bulbasaur hits and does 4 damage to their opponent. Some attacks have an added special ability. On the other side of Bulbasaur, for example, their Leech Seed attack does 1 Hit on a roll of 3-6, but in addition, the player gets to flip a coin, and on heads, Bulbasaur can attack with Leech Seed again. Because within the Pokemon universe Bulbasaur has more attacks than Leech Seed and Tackle, you can have multiple Bulbasaur cards, each with different learned attacks. At the time the game was made there was no way to turn your Bulbasaur into an Ivysaur or to teach them more attacks. And since the game was quickly discontinued, we’ll never know what they planned to do in future expansions. I can see why they would want to keep the game simple at first, and grow it in complexity with future products, and the designers clearly left room in the game for that growth. I would love to have seen where they took the game. I had time last night to flesh out one more idea I had for a checklist NPC. This one demanded a different format. If you get a chance to play it, I'd love to hear about it! The Stranger on a Train

A chance meeting. A sharing of troubles. An idea. You solve his problem, and he’ll solve yours. He solves your problem:

His problem requires: