|

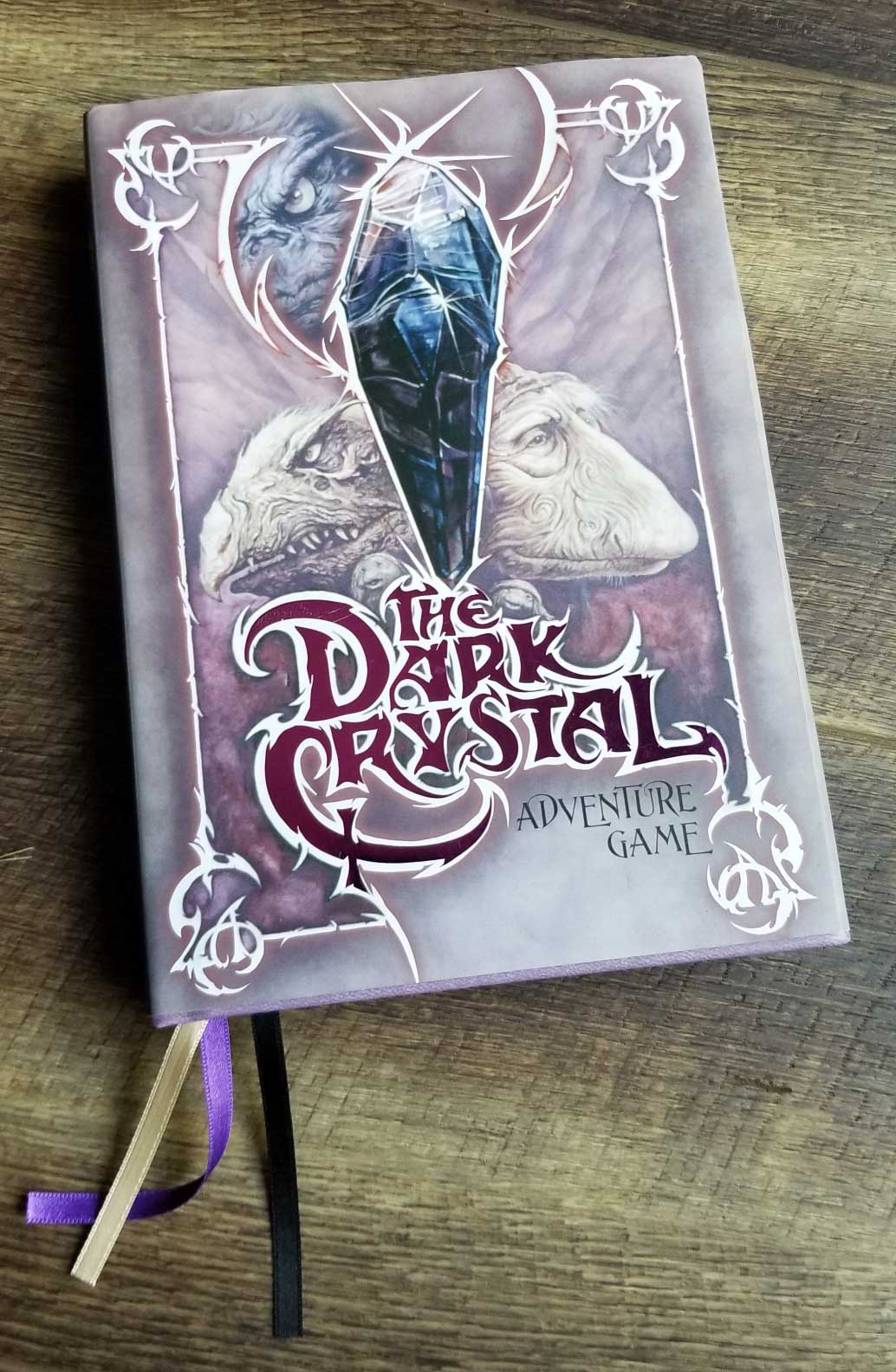

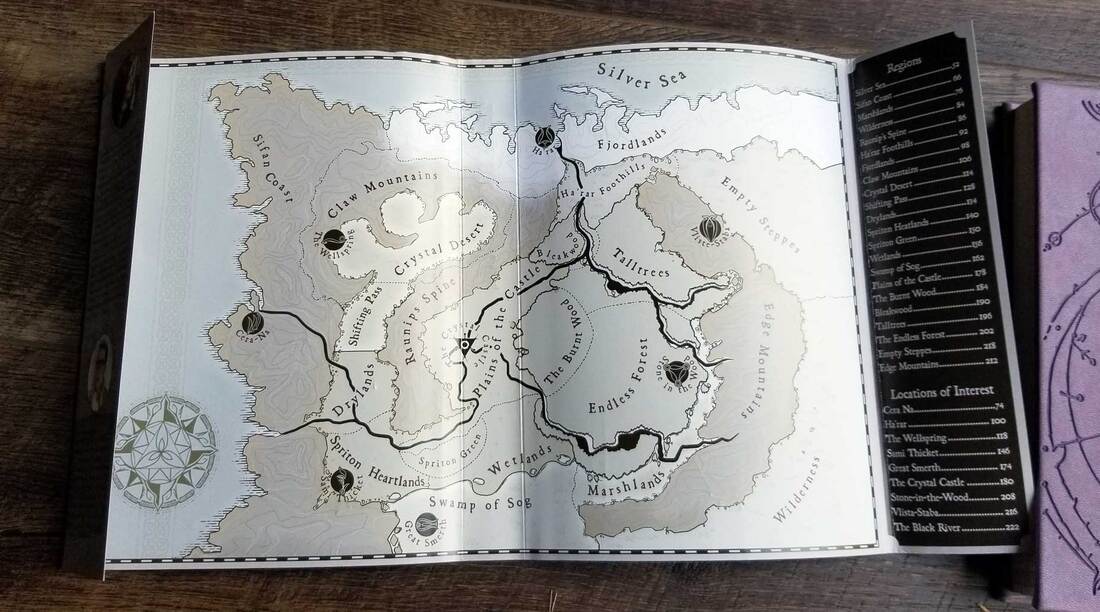

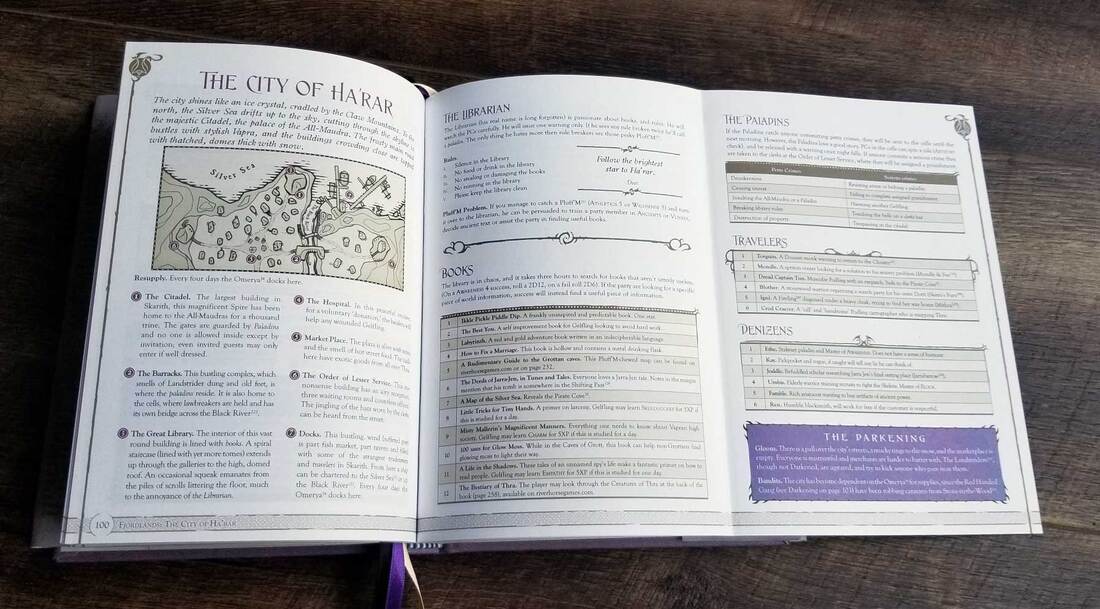

I picked up this book at a local game store for a handful of reasons. First, I was looking to buy something –that’s no small thing in itself. Second, the book itself is very beautiful—it has a lovely color palette, is full of maps and tables and art, has pages that fold out, and even has a few vellum pages that allow the maps to layer. Third, my wife has a long-lived love of the original movie, and I was looking for something the two of us could play one-on-one in short bursts over the summer. Because of all those beautiful features, the book is not cheap, coming in at about $45 for a 300-page, hardbound, digest-sized book. Actually, the quality is not the sole cause of the high cost—there is a lot of game material in this book, a whole world created and parceled out to be the focus of high adventure. You get a lot for your money here, and for that reason, the book is reasonably priced. The game itself is related to a lot of OSR-type RPGs. You have an adventuring party; you use a full set of polyhedral dice; play roles are divided between a GM and players; your characters are defined by their skills, strengths, and weaknesses; your characters track their health and suffer consequences when their health is low; your character has traits that help them achieve tasks or allow them to do things they otherwise couldn’t do; your character’s equipment matters and is limited by the rules of the game; your character has a particular cultural background that informs what they know and what they can do; there is an experience system by which your characters improve over time to be more powerful, more efficient, and more effective; you roll dice when your character attempts to do something with an uncertain outcome, with the roll determining success or failure. Play itself is a matter of the GM setting the scene, players saying what their characters do in response, and the GM having the world respond to those reactions in kind. Gelflings are fragile creatures, and some of the encounters are dangerous, so the facts of the game encourages players to play cautiously to protect their characters, even as those same characters are heroes, set up to save all of Thra from The Darkening. At its root, The Dark Crystal Adventure Game is a game of exploration. While players are expected to be familiar with the world through the original movie and, more pertinently, the Netflix limited series The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance (the same time period in which the game is set), the specifics of the world and the regions explored are necessarily a mystery to the players. The map of the world takes into consideration maps that have come before, but the geography is entirely new. Moreover, the quest presented to the players depends on the players not knowing exactly where to go. The players are given a map of the world, divided into 22 regions, with only major cities and areas marked. Your character may have bits of information about the world depending on what type of Gelfling they are, but that information is only general. This design decision, I assume, is so that the players can experience the same sense of surprise and wonder at Jim Henson’s world even when they are playing inhabitants of that world. The mechanics are stripped down and rather straightforward, using a lot of techniques developed by indie designers. For example, the damage rules are elegant and simple. All health is given a die size for its rating. Gelflings all have a d6 health. When you take a wound, you reduce your die size by one. So a single wound brings a Gelfling to a d4. If you take a wound at d4, then you roll a d12 on a random injury table to find out your fate, which ranges from getting a scar to losing a limb to death. Combat is less exciting, consisting of a series of rolls to determine if you hit or if you dodge a blow. The GM does not roll, but the player does roll separately for attack and defense. So the first round you try to wound your opponent and the following round you try to avoid a wound yourself. The one little spice to the combat system is that fighters are trained in either finesse or ferocity, attacking with brute strength or dexterous sword play. The cool thing about that is that some creatures can only be wounded by finesse because their armored shells can withstand brute force, while others can resist finesse but suffer against ferocity. As a result, you’re not ever just good at killing all things. Whether your battling or trying to overcome an obstacle, everything is a Test, in the language of the game, with a target number determined by the GM. Your skill or ability determines what size dice you roll to accomplish the goal. There is also an advantage and disadvantage system, like so many games now, that allows you to roll two dice and take the higher roll or force you to roll two dice and take the lowest roll. In short, the mechanics work and are well designed but not especially noteworthy. There is little in the game that requires you to use these particular mechanics and you could just as easily use whatever system you want to play within the world presented in the rest of the book. The bulk of the book, a full 200 pages, are used for the included adventure. That’s a funny way to put it because it is itself designed to be a single adventure, though you can certainly use the content in whatever way you choose. The basic setup is that all the player’s characters have come to the Mystic Valley for one reason or another, where they are informed that in order to save Thra from The Darkening, they must gather up a seed from each of the seven great trees and return them to the Mystic Valley within the next 99 days, or a great calamity will befall Thra. Then the characters are let loose to wander Thra, find the trees, collect the seeds, and return as the days tick on. The designers can’t expect you to commit to memory all the ins and outs of the entire world, so they designed the book to be easy to reference and work with on the fly. Each location in the world, be it a full region or a single encampment is given a two-page spread, clearly labeled and easy to navigate. If too much information is required for the spread, the pages will fold out to give you the extra space needed without ever breaking the two-page layout for what follows and precedes. The locations are essentially nested within each other to make moving from one place to another easy. What I mean by that is that each region is given a two-page spread. The 6-8 locations of interest within a region follow that two page spread, and if there is sub-locations within those, they follow the location they are subordinate to. So, for example, there is a spread for the Silver Sea, that tells me what the 6 locations within that region are. I also get a random encounter to use within the Silver Sea while characters are traveling from one location to another. Then each of those locations are presented as 6 separate two-page spreads that follow the Silver Sea spread. So when the characters to the Dreaming Isles, I go to that spread and have everything I need for that part of the adventure there. And when they leave the Dreaming Isle, I turn back to the Silver Sea spread for everything I need until they arrive at their next location within the Silver Sea Region. When they leave the region, I just turn to the neighboring region and repeat the process. If you’ve given a cursory read through the book, then all that should be required to orient yourself is two minutes of skimming. Obviously what is presented in so small a spread are just the bare bones. You get the names and motivations of any anticipated NPCs and the details of any special items. Then it is up to you to make that part of the adventure as detailed or as high-level as you want. You can quickly talk your way through an encounter to get to the next location, or you can slow down and role play the entire conversation, bringing the NPCs to full life. You can have a whole session take place in a small market or fly through a whole region in a couple of sentences. The designers had fun connecting characters and regions and events so that the NPC you meet here has ties to a family in this other region over here. The wandering creature you can encounter here belongs to this shepherd who is looking obsessively for them over here. You can play it as randomly as you liked, using the tables either for inspiration or strictly by the die roll to see how the world comes into focus over time. Reading through the spreads you get a full sense of the world and all the connections holding the place together, making it dimensional and alive. Even just as a read it’s a fun experience.

And now for the coolest part of the game. Remember those 99 days that the players have to complete their mission. You, the GM, actually have a calendar by which you track those 99 days. You can play out the passage of time through reason, but each region lets you know how many days it takes to cross the region, so simply moving will push that clock forward. Dotted on the calendar are days marked in purple, and when you reach one of those days, you choose a region to experience The Darkening. At the beginning of the game, only the Plains of the Castle, where the Crystal Castle sits, are Darkened. And as the purple days are reached, the Darkening spreads to a neighboring region, which you can choose or decide randomly. Each location spread includes a purple box that tell you how the region is changed when it’s Darkened. Typically, creatures become more ferocious and NPCs become ruder, more selfish, and even violent. Weather can get severe and crops can fail. To me, that’s an exciting feature, because even reading through the spreads, you have no idea what the region will be like when the players’ characters finally get there. And the more time passes, the more trouble they will encounter. It’s a game-wide clock that adds life and excitement to the whole setup, in my eyes. And the design of the calendar is cool, as they made the sheet into a GM note page, where you mark what NPCs have been encountered, what regions have been Darkened, and any notes about things you want to remember to bring back later in the game. I mentioned earlier that the game has a built-in experience system. The system itself is unremarkable, but one aspect about it I do enjoy. Each skill a character can have has three levels of mastery: trained, specialization, mastery. The only way to attain that last rank, mastery, is to spend XP to have an NPC train you. So players are encouraged to save their XP and talk to NPCs to find out whom they can learn from. When they meet the right person and have the XP available to them, then they can train with them in the fiction and attain the mastery rank. It’s a minor feature of the game, but I think it’s cool. Originally, I planned on using the rules as written to run the game with my wife, but I’m tending away from that now, primarily because the test system really only cares about success and failures. That’s never a design that excites me, but it can be especially disastrous with one-on-one play. For an example from the adventure, there is some random encounter that has the characters come across a trap and fall into a pit if they don’t roll some target number. With 4 or 5 characters, one of them is likely to succeed in the roll and then they can work to get their friends out. With one character, if you whiff, you are then stuck in a pit until some NPC character comes along to help you out or until you roll a successful roll of some sort to escape. The latter is unexciting. The former is predictable. Neither makes for a fun session. I put off writing this review because I was hoping to put in a number of sessions before I did so. Life has intervened with my play plans, so I’m writing this now before I forget the system. I might write a follow-up when I finally get to play. Even without playing, the reading and the journey in my own mind was enjoyable enough to cover the cost of admission, for me. If this is up your alley, it’s probably worth checking out.

0 Comments

|

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed