I want to talk about Vincent and Meguey Baker’s game Bedlam Beautiful. The game isn't officially released yet, so let me take a moment to explain how the game works. (Sorry to talk about a game that isn't released, but when I wrote this, I thought it was--oops!) It’s a three-player game, and like Mobile Frame Zero: Firebrands, Murderous Ghosts, and The King is Dead, it is a booklet-based game. During play, each player has a copy of the book, which contains the rules, explanatory information, and lists from which the players can choose during their turn. Here’s how the text summarizes the division of play: To play Bedlam Beautiful, you’ll need three players. Player one is called, ‘the player.’ Players two and three are called, ‘the system and the disease,” without regard for which might be which. There is no need, you see, to distinguish them. Decide now which of you will be ‘the player.’ The remainder become ‘they system and the disease (1). Okay. The conceit of the game is that the “player” plays a person (she’s referred to as “she” in the text) who has been institutionalized in English Victorian period, named Mad Maudlin. The system and the disease players portray characters visiting Mad Maudlin. Only, none of that is true. As the text says, “The player’s true character and circumstances are ambiguous. It’s appropriate for all of you to speculate and imagine what they might be, but there is no way to know for sure, and no need to assert your opinions” (3). So yeah, you cannot know what the reality is even as you play the game. Talk and speculate amongst yourselves if you like, but no amount of asserting will make a thing true because the “truth” isn’t relevant to the game. What is important is that Mad Maudlin is searching through the cast of characters portrayed by the system and the disease for her true love, Tom O’Bedlam. But the player is never certain who the system and the disease are playing at any given moment. To some extent the game is a deduction game. The game is played with 13 playing cards, each card representing a specific character. At the beginning of each round, the system and the disease draw a card from the small deck, check their booklet to see who that card represents and what that character’s goals and nature are, and then set a scene from the list of options in the booklet, placing Mad Maudlin and this new character together. On Mad Maudlin’s turn, the player selects a question from her list and asks it of the character played by the system and the disease, who in turn selects an answer from their own list. The exchanges go back and forth until the Mad Maudlin character asks to be left alone, shuts up, lashes out, flees the scene, or chooses to stay with the other character forevermore. Here’s each player’s goal as described by the text: For the player, the object of the game is to find Tom O’Bedlam, the Joker in the deck. For the system and the disease, the object of the game is to provoke the player to shut up forever, or to kill, and the more the better (1).

That’s the back and forth of play. The system and the disease go through the 13 character cards, trying to get the player to shut up or kill as much as they can while the player wants to discern which character is Tom O’Bedlam and choose Tom as her love. There are so many interesting things to talk about with this game, but the one I want to focus on is the difficulty of winning the game, and how the rules give the player a fair shot in what is inarguably an unfair world. Just looking at the goal of the game, it is hard to see how the player could ever win. The system and the disease players control all the information that the player will ever receive. They portray all of the characters and can decide as they please how to respond to the player’s questions. They could easily mislead the player into thinking Dr. Walter Freeman (“the inventor of the transorbital, or ‘ice pick,’ lobotomy”) is her Tom O’Bedlam, or trick her into killing the “real” Tom O’Bedlam. So what is to prevent that from happening? A number of things, really. First, the system and the disease are played by two players, not one. This is not because they are separate entities. The text repeatedly makes clear that the distinction is one of name only; remember, “There is no need, you see, to distinguish them.” The system and the disease players are not supposed to play the separate rolls, one the system and one the disease, but to both together be both the system and the disease. Similarly, even though the system and the disease keep separate scores as determined by the player’s actions, the game makes it clear that it doesn’t matter which of the two wins, only that the player loses: “Report the final total victory scores: ‘—for the system, -- for the disease.’ If the system’s score is higher, the system wins; if the disease score is higher, the disease wins. A tie is possible. It makes no difference” (10). So the two players play one role, and when playing the characters in the scene, “They must agree to their answer and give it promptly” (2). With this construction it becomes clear that it’s important to the design to have two separate heads making decisions as the system and the disease. The game could be a two-player game, but the designers want the system and the disease to be a split entity even though they act as one. The second feature of the game that gives the player a chance at winning is related to the first. The system and the disease are given contradictory rules for behavior. On the one hand, they are told their goal is “to provoke the player to shut up forever, or to kill, and the more the better.” But on the other hand, they are told to follow the instincts and natures of the individual characters that they play: “They take upon them the role of the figure represented by the card” (2). The system and the disease players are asked to try to get the player to shut up or kill while simultaneously playing Tom O’Bedlam and the other figures true to their nature. These two requirements of the system and the disease clash, if not outright contradict each other. Not only are the system and the disease player then one player with two minds but they are tasked with serving two masters. This dissonance provides a crack into which the player can slip to sway the system and the disease to get them to sympathize with her, to take pity on her, and even to root for her against their own game-dictated interests. The player’s lack of power is made clear by the setup, obviously, but also by the questions she is allowed to ask of her interlocutor. All she can express is what she’d “like” her companion to do, and then ask if her companion will do it. What she asks for in all her questions is sympathy, support, love, kindness, and acceptance. To these repeated requests, the system and the disease players, both, have to repeatedly be awful to the player. So is it any surprise that when the system and the disease have permission to be kind to the player while playing, say, the gentlewoman or Tom O’Bedlam or any of the more gentle-seeming figures that they seize upon it, giving nudges and signals to the player about whom to trust and whom not to trust? Each game becomes something of a social experiment between the players.

0 Comments

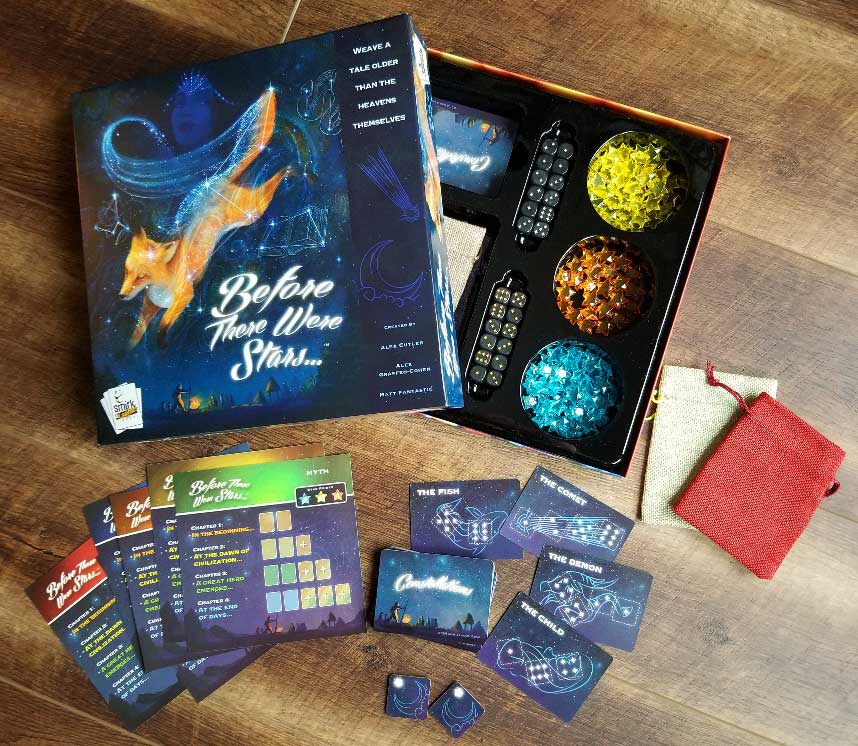

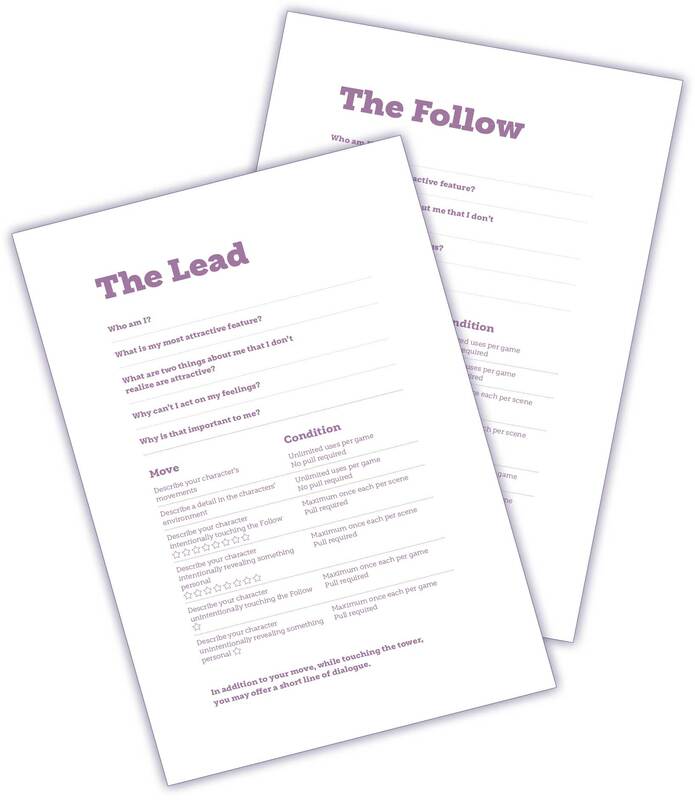

Before There Were Stars . . . is a boxed game (I suppose it’s categorized as a board game although there is no board) by Smirk & Laughter, the non-backstabbing-games division of Smirk & Dagger. I don’t normally analyze or review board games, but this game is really a story game masquerading as a board game, and it’s a cool one at that. The central component of the game is a set of constellation cards. Represented on each card is a set of two to four d6 faces, with the pips of the dice creating the stars of the constellation, around which is a sketch of the thing the constellation represents. Each constellation has a name, a narrative element to be used in the myths that you will create through game play. Some example cards are The Volcano, The Desert, The Angel, The Spy, The Chest, and The Child. Each player has a “Story Card” with four story prompts, one for each round of play. The four prompts are “In the beginning . . .” “At the dawn of civilization . . .” “A great hero emerges . . . “ and “At the end of days . . .” Each round consists of three phases. The first phase is called the stargazing phase. In the stargazing phase the top 5 cards of the constellation deck are turned face up. Players then take turns rolling 12d6 and select one of the constellations whose die faces match the dice available to you from your roll. If there are no matches available, you draw from the top of the deck. The cards chosen are replaced after each selection so that each player always has five cards for chose from. After each player has two cards, the stargazing phase ends. I like the mixture of choice and limitations that this setup provides. On a good dice roll, you can pick any of the constellations you want. On a bad roll, you get no choice at all. Usually, you’ll end up somewhere in the middle. Either way, you have reasonable constraints that create excitement and pressure on a minor scale which makes the player think critically about their choices. Further, you will naturally pay attention during other players’ rolls, especially if there is a constellation you are hoping will still be there when it’s your turn again. These pressures and constraints can lead to players creating combinations and storylines that they would never come up with without them. That element of being able to surprise yourself is critical to good story game. Or at least, it can be. Now the storytelling phase begins. Taking turns, each player takes a moment to think of the story they will tell using the two constellation cards they collected and the story prompt for that round, and one by one they tell a short, simple myth in about 60 seconds. Here’s the example from the rulebook: “In Chapter 1, Melodee has chosen the Constellation BOOK and VALLEY. She gets ready, starts the timer and begins, speaking in a voice that all can hear . . . ‘In the Beginning, the All-Mother poured all of her knowledge into a gigantic book, so that she could one day share it with her children. But as all was still void, there was nowhere to raise her family. So, she took the book in her hand and opened it at its center. The pages unfurled, forming a great valley, where her children could now grow and prosper.’” The 60 second timer is not a strict measure. Players can go way under or way over the time if they wish. The 60 seconds is a good target, in that it emphasizes that the players are not expected to develop anything overly complex or detailed, and it is designed to keep the pressure on any given story low. It seems counter-intuitive to use a timer to relieve pressure instead of building pressure, which is why I think they created a special timer app for the game. The image on the app is of people around a campfire under a star-filled sky. As the time counts down, the star wheel overhead and the sky lightens until it looks like morning when the timer reaches zero. As the timer progresses, you hear the sounds of crickets and peepers and other night animals, a kind of white noise that serves to create the atmosphere of stories told communally around a campfire. Once time is up, the night animal sounds give way to a chirping bird announcing the rising sun. All the sounds or unobtrusive and pleasant, rather than alarming. After the storytelling phase is the appreciation phase, in which the players reward the other players for the stories they told. We’ll come back to that in a minute. These three phases repeat for the four rounds. In the subsequent rounds, you select two additional constellations that you must use as the basis for your next story following the prompt for that round. But in addition, you must also re-use a minimum number of the cards you used in previous rounds. Bringing in these earlier cards allows you to stitch the elements of your myth together so that the body of your myths have internal consistency and narrative echoes. It’s a neat and easy way to unite what could otherwise be four disparate tales. Now, back to the appreciation phase. This phase amounts to a scoring system which lets the game have a “winner.” Here’s how the scoring works. There are three types of plastic stars that come with the game: blue, yellow, and gold. Each star is worth 2, 3, and 4 points, respectively. These stars sit as a pool in the middle of the table, and after each round, players get a number of stars equal to the number of players minus one. There is a chart in the rules that tells you how many and what kind of stars each player has access to depending on the number of players playing. The players then pass around color-coded cloth bags and drop a star in each bag that is not your own, essentially scoring the other players’ stories. The stars and their points are not looked at until the end of the game, so they do not act as feedback, but as unknown information. After the final appreciation round, before points are totaled up, each player gives a moon token to one other player that they feel had the “best story moment” and tells what that moment was. This is the only organized praise and spoken feedback of the game. The stars and moon are specifically said to celebrate the “best story moment” rather than the “best performance” or the “best story” so that any singularly gifted storyteller doesn’t end up with all the points. So you can point out a cool or surprising moment, a neat way to combine unexpected constellations, an awesome callback to an earlier event—whatever impresses or surprises or delights you. I really like the idea of distributing praise this way, though I’m not crazy about points being tied up with it. I get why the stars are hidden information until the end of the game. You don’t want players getting discouraged that their stories are getting few points, because that would be no fun. But that’s part of the problem with rating your fellow storytellers using points, isn’t it. As soon as points are on the table, you are asking the players to care about those points and to strive for those points. If they follow your lead, then their pleasure and purpose is wrapped up with those points. If they don’t, then the points are useless and just muddy up the gaming experience. I would rather see something like the moon token exchange happen after each round so that players are getting constant feedback and encouragement. I’m sure that that happens naturally anyway (“Oh wow, that was cool!” “I love the way you tied those together” or even stunned and impressed silence) but I’m all in favor of mechanizing that feedback. Before There Were Stars . . . is a well-designed, neat game, with sharp, simple rules and quality components and art. It’s a great quick game for players who love stories and storytelling.  I’ve been excited about Companions’ Tale since I first learned of its existence. I love map games, I love story games, and I love stories of competing narrative authority. Unreliable narrators and the mutability of reality through the lens of human experience both fascinate me. Companions’ Tale has it all. In Companions’ Tale, you and three friends tell the stories of a land and one of its heroes by sharing the adventures of the companions who have accompanied that hero. No one plays the hero, and the hero never has their own voice; instead, they are an empty center whose shape and substance is determined by the competing actions, words, and stories of others. The game takes place over 20 rounds of play, consisting of a prologue, three acts, and an epilogue. Each act is made up of 6 rounds: an historian phrase, four story rounds, and a biographer phase. Finally, each story round consists of each player playing one of four specific roles: the cartographer, the companion, the witness, and the lorekeeper. In the prologue, each player answers a question about the world, then draws a representation of their answer on a communal map. This round covers basic aspects of the world, establishing the major geographical feature of the landscape, the most prized virtue of the people who live there, some central beliefs, a basic power structure, and the nature of magic or technology in the world. It’s a solid way to bring the fictional world to life in a few deft strokes. The structure allows each player to have a say in the matter while never arriving at a group consensus. Most story games want to avoid running by consensus to keep the fiction from being developed by committee, which can quickly suck the life and excitement out of the game. But Companions’ Tale is specifically interested in keeping players from reaching consensus because the game probes the way people experience the world differently, often forcing their interpretation of events on others. To this end, players are invited through the various roles available to them in play to comment upon and “correct” the other competing narratives. (I mean “competing” in a Darwinian sense, not in the sense that some games are competitive. There is no “winner” in a game of Companions’ Tale.) After the prologue, the players play through the three acts. Each act begins with the Historian Phase, in which each player chooses a place on the map and details an historical event that has occurred there. To give the players guidance and to make the events thematically connected, the players first draw a single Theme Card from the Theme Deck that all the historical events must reflect. Some sample themes are hunger, justice, anticipation, captivity, and creation. There are 36 theme cards. The Historian Phase serves two major purposes. The first is to build out the world to give the players more material to use in the fiction during the rest of the game. The second is to give another outlet for players to correct or comment upon what other players have created on their turns. This purpose might seem ill-served by the mechanic at first blush since the players in the Historian Phase have to introduce a newly reveled historical moment (rather than, say, revising or updating a previously discussed historical event), but players can create histories that undermine, support, or mitigate what other players have previously established on their turns. This second purpose is especially served by the Historian Phases of the second and third acts. After every player contributes something in the Historian Phase, the story rounds commence. There are four roles assumed by each player in the story round. The cartographer is in charge of translating things said by the other players onto the communal map. They go first in the round, and during their turn, they must select a singe event from the last round and make adjustments to the map as they see fit. The companion player goes next. Their turn is always the longest and most significant. They begin by selecting one of the four companion cards face up in the middle of the table. The companion cards each name a relationship that the companion has with the hero, such as ally, lover, rival, childhood friend, rescued, mentor, etc. There are 18 companion cards. After the player selects their role, they draw a card from the Face Deck to see what the companion looks like. The Face Card is just what it sounds like, a deck of cards with faces. The 20 face cards are beautifully illustrated. Then the player draws two cards from the Theme Deck, the same deck that the players drew from in the Historian Phase, and select one of the cards to be the theme for the story they are to tell. In addition to have a broad theme, each Theme Card has one or two story prompts, such as “Once, a new domain of knowledge was released into the world”; “Once, a judge’s wrath exceeded the slight“; “Once, blood paid for blood”; and “Once, heretical forces held sway over the land.” Having a relationship, a look, and a thematic story prompt, the player tells a brief story from the companion’s point of view about an adventure the companions shared with the hero. The next role played is the witness. On their turn, they select some region of the map different from where the companion player set their tale and gives a few “facts” about the goings on in that area since it was last talked about in the game. These “facts” can build off what has come before, elaborating on, revising, or contradicting what other players have said. This keeps the world growing and developing as well as creating new material for future scenes. The final role of the round is the lorekeeper, who describes some aspect of culture in the realm, such as a song sung, myths told, murals painted, or sports played. Presumably the player will draw on the material that has come before, but that is not required by the rules in the rulebook. The roles rotate each round until all the players have played all the roles. The act concludes with the Biographer Phase, in which each player assumes the role of one of the hero’s many biographers by selecting a companion controlled by another player and describing “something unfortunate, amusing, or scandalous about the other player’s companion” (11). Act II plays out the same way as Act I so that at the end of the second act each player has two somewhat fleshed-out companions in front of them. Act II again plays out the same was as the two previous acts except that instead of selecting a third companion, the companion player picks one of her two already-existing companions to tell her tale. Moreover, instead of drawing a new theme card, the players shuffle together all the theme cards previously used in the Historian Phases and the players’ companion rounds, including the theme cards they didn’t select, and use that new deck from which to draw her two possible theme cards. Once the third act is played out, then a brief epilogue round is played, in which each player says a few words about the last time their companions ever saw the hero. The player can choose to provide an epilogue for one or both of their companions. Neat, right? Over the course of the game, you develop a world with 12 historical events that provide the groundwork on which the other stories can be built and a colorful narrative for a hero as seen through the eyes of eight companions and the deeds of eight adventures. The companions themselves have presumably put their best feet forward and have been undercut by three biographical revelations about them. And of course you have a map that marks all of these occurrences and details. All that is what I can see from having read the rules, looked at the cards, and imagined play. There are concerns I have about how play will play out which I can’t address without actually playing the game (which I want to do and plan to do). For example, we are advised as players to push things to a crisis in the second act by “introduc[ing] some growing threats that will set the world into chaos for Act III” (12), but how to make that happen is left up entirely to the players. There’s not a separate set of cards or story prompts that naturally escalate conflict or create lasting threats. Similarly, the third act is supposed to bring things to a climactic close (“If the world is not teetering on the edge of disaster, now is time to give a healthy shove” (13)), but that’s mere play advice without anything mechanical to help or make that happen. Now, it could be that it’s natural in play that this all comes about, but I don’t see any reason why that should be so. But it might. Only play will tell. The design mitigates my concerns to some extent by attempting to create throughlines and consistency in the stories and the world. The map of course creates physical relationships for everything added by the stories. Then using a theme card during the Historian Phase creates unified thematic backdrops for the history of the world. Having players use existing companions and draw from already-seen Theme Cards in the third act increases chances that the stories will be able to recall earlier events and concerns smoothly. Perhaps in play, these tools are sufficient to make the second act build and the third act resonate. Again, only play will tell. Another concern I have is that while the game gives the players some good material to tell their tales when acting in the role of companions, it still puts a lot of pressure on the player to turn that prompt and relationship into a story to share with the table. I can imagine players seizing up, wanting to impress the other players but not knowing how to get there. For example, you’re the hero’s ally and you have the theme of debt with the story prompt, “Once, a substantial debt was overdue.” Now tell a story. That is certainly great material, but is it enough to let you say something that excites, surprises, and pleases yourself, let alone your friends? Part of the difficulty is that you are responsible for this free-standing story in its entirety, so even this small task can be challenging. A lot of games lighten the load by spreading elements of the narrative across the table so no one player has to do all the heavy lifting. There are some friends I’d be nervous to invite to play the game because even though I know they’d love everything else about the game, that moment of being in the spotlight alone would be unpleasant for them. I love that the game calls into question what history is, what maps are, and what biographies are. Each one of these art forms can pretend to be the capital-T Truth, impartial and imperial. The game lays bare that human hands and hearts shape each of these arts, creating artifacts that are then handed down as authoritative things. I expect the game will inspire other to further hone this idea. Companions’ Tale creates a fun romp in which many hands change the map, many mouths shape the biographies, and many minds affect the official histories. In our real world, of course, dominant forces decide the orientation of the map, the subject of biographies, and the content of history books. There are many places to take this idea.  When I backed Star Crossed on Kickstarter, I was irritated that there was no backer level for just the physical book. To get the physical book, you had to also get a boxed set that came complete with a tumbling block tower set, which I didn’t want. Now, reading the booklet and having read Jessica Hammer’s 4/12/2012 blogpost titled “Making Horror, Selling Dread” (http://replayable.net/making-horror-selling-dread/), I understand what the good folks at Bully Pulpit Games were thinking. They are marketing and selling Star Crossed as a full boxed game, and the booklet is really just a rules booklet, like one that would be included in any board game. To that end, they created a beautiful, concise, crisp rulebook. The rulebook contains nothing extraneous, but nothing is missing. It’s an impressive feat, and I expect it will be a model for a certain type of RPG going forward. In fact, I don’t believe the word “roleplaying” occurs anywhere in the booklet—it’s simply a “game.” (Of course, now that I look around, I see a lot of precursors as well.) The game is designed to be played by two people in less than two hours, during which they create a story of forbidden love. Inspired by Dread, the game uses a “tumbling brick tower” to manifest the tension of the story unfolding as the two characters desperately want to get it on but have their own reasons for not acting on their passions. How close can they get to the fire without getting burned? Will they give in to their passions? If they do, how will it end for them? These are the questions the game poses and play seeks to answer. Characters are created entirely within the fiction. The players together create a general situation, roughly sketching who the characters are and what the barrier to their passions is. Once that basic situation is agreed upon, the players create their individual characters by answer the same five questions. Each player answer “Who am I?” and “What is my most attractive feature?” These questions establish a fictional foundation and a defining trait that is central to the player’s vision. Then each player names two things about the other player’s character that their character finds attractive. This question makes both players have a stake in both characters and it lays the foundation for why these characters want each other. It gives us the starting point to believe that their passion is real. They have have to answer the final two questions: “Why can’t I act on my feelings?” and “Why is that important to me?” This has to be something the player can believe in on behalf of their character. The twin poles of passion and opposition need to be of near-equal strength. If well-constructed, the players themselves won’t know which force is stronger, and if the game ends without the tower tumbling, it needs to completely believable to the players. That tension is in fact as important as the sexual tension between the characters. Those five questions give the players everything they need to create the fiction of the game. Well, actually, one more thing is needed. Once all the tensions and vectors of force are in place, there needs to be a way to keep the scenes from being repetitive and uninteresting. The game has two critical solutions to this problem. The first is a simple narrative role for each character: the lead and the follow. By making one character the lead and the other the follow, the game establishes an inequality of energy between the characters that gives each character their own presence in every scene and prevents the story from devolving into a lot of uncharged or equally charged dullness. It is a simple, elegant, and brilliant solution. The second solution is the set of scene cards that give the players a single prompt to spur them in scene creation. The cards are gentle pushes to jumpstart the engines of the players’ imaginations while simultaneously creating a gentle story arc if the block keeps standing. Things build easily and get more intense, and of course the intensity is coupled with an increasingly rickety tower and the ever-growing danger of spoken words of dialogue as players are more hesitant to engage in in-character dialogue, since they can only do so when they are physically touching the tower. So how do you explain roleplaying in a game that doesn’t even use the word? How do you tell players what they can say and when they can say it? How do you explain freeform play and when bricks need to be pulled? Goddamn, but their solution is brilliant Each character sheet has a list of “moves.” Us experienced roleplayers will see that and think of moves like in Apocalypse World, but an experienced boardgame player will merely think of legal moves available to a player. Players are invited to describe what their character does and to describe the environment of the scene as much as they want without having to pull a brick. Twice per scene, they can describe their character touching the other character (once) and revealing something intimate about themselves to the other player (once). When they do so, then they have to pull a brick and mark their sheet. The lead touches and reveals things intentionally, while the follow touches and reveals things unintentionally. But twice per game, they can do the opposite touching once and revealing once intentionally instead of unintentionally and vice versa, again for the cost of a brick pull. It’s so simple to look at the sheet and see what you can do, and of course players know exactly the type of story being told, so they only need the slightest prompting. With 8 scenes, each player has the potential to pull 18 bricks in the game. Eventually either the tower falls, or the scenes run their course and the game ends with the tower still standing. The epilogue happens when either of those conditions are met, and the prompt for the epilogue is determined by the number of bricks pulled during the game. The number of bricks pulled is called the “attraction score.” If less than 10 bricks are pulled, “you reveal too much, too soon, and the connection is irrevocably broken.” 11-13 bricks mean that “Passion burns bright, but fizzes quickly.” 14-16 results in “An uneasy intimacy.” 17-19 prompts the players to narrate a “Sweet, cherished love, with the bitter certainty of loss.” If you reach 20 or more bricks between the two of you, then the game suggests your passions have simmered long enough, cooked to proper piquancy, and “From now on, you only need each other.” I found the epilogue to be an interesting collection of options. They make a statement about passion and sexual tension so that the game itself makes that statement. There is a proposed relationship between passion and its constraint, and by the options available, either you are destined to be together forever or you are doomed to love lost. I find the 17-19 option especially interesting since the prompt doesn’t suggest possible loss, but certain loss. That certainty colors the interpretation of the 14-16 result, suggesting the uneasy intimacy is doomed; the characters just don’t know it. In short, the game is eager to set up a poignant story of heartbreak and has a generally pessimistic opinion of love rooted in sexual attraction. It makes sense to some extent because the obstacles presented in play have to be significant, and they can’t just be washed away in the epilogue. If I had the intellectual determination and insight, I’d keep pulling about this epilogue chart to analyze what is actually being said by the game about constrained passion. The game is tightly designed providing players with all the tools they need while giving them no room to wander. By making every brick pull tied to touches and revelations, players are rewarded for taking their scenes as close to the edge as they can while their desire to succeed in their pull keeps their characters apart. But if you truly want the characters to have a happy ending, you want to keep them constrained for at least 20 pulls. It’s really a fantastic feat of game design. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed