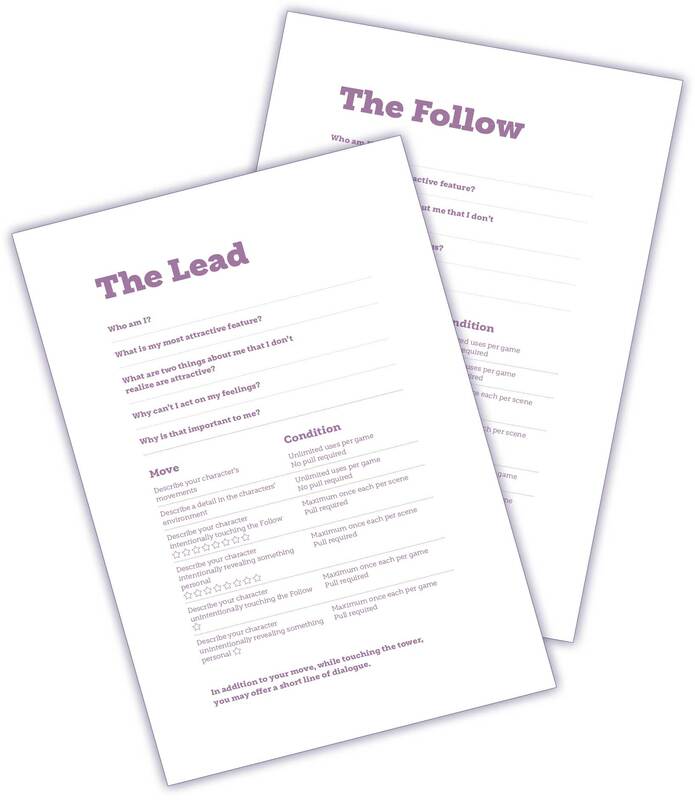

When I backed Star Crossed on Kickstarter, I was irritated that there was no backer level for just the physical book. To get the physical book, you had to also get a boxed set that came complete with a tumbling block tower set, which I didn’t want. Now, reading the booklet and having read Jessica Hammer’s 4/12/2012 blogpost titled “Making Horror, Selling Dread” (http://replayable.net/making-horror-selling-dread/), I understand what the good folks at Bully Pulpit Games were thinking. They are marketing and selling Star Crossed as a full boxed game, and the booklet is really just a rules booklet, like one that would be included in any board game. To that end, they created a beautiful, concise, crisp rulebook. The rulebook contains nothing extraneous, but nothing is missing. It’s an impressive feat, and I expect it will be a model for a certain type of RPG going forward. In fact, I don’t believe the word “roleplaying” occurs anywhere in the booklet—it’s simply a “game.” (Of course, now that I look around, I see a lot of precursors as well.) The game is designed to be played by two people in less than two hours, during which they create a story of forbidden love. Inspired by Dread, the game uses a “tumbling brick tower” to manifest the tension of the story unfolding as the two characters desperately want to get it on but have their own reasons for not acting on their passions. How close can they get to the fire without getting burned? Will they give in to their passions? If they do, how will it end for them? These are the questions the game poses and play seeks to answer. Characters are created entirely within the fiction. The players together create a general situation, roughly sketching who the characters are and what the barrier to their passions is. Once that basic situation is agreed upon, the players create their individual characters by answer the same five questions. Each player answer “Who am I?” and “What is my most attractive feature?” These questions establish a fictional foundation and a defining trait that is central to the player’s vision. Then each player names two things about the other player’s character that their character finds attractive. This question makes both players have a stake in both characters and it lays the foundation for why these characters want each other. It gives us the starting point to believe that their passion is real. They have have to answer the final two questions: “Why can’t I act on my feelings?” and “Why is that important to me?” This has to be something the player can believe in on behalf of their character. The twin poles of passion and opposition need to be of near-equal strength. If well-constructed, the players themselves won’t know which force is stronger, and if the game ends without the tower tumbling, it needs to completely believable to the players. That tension is in fact as important as the sexual tension between the characters. Those five questions give the players everything they need to create the fiction of the game. Well, actually, one more thing is needed. Once all the tensions and vectors of force are in place, there needs to be a way to keep the scenes from being repetitive and uninteresting. The game has two critical solutions to this problem. The first is a simple narrative role for each character: the lead and the follow. By making one character the lead and the other the follow, the game establishes an inequality of energy between the characters that gives each character their own presence in every scene and prevents the story from devolving into a lot of uncharged or equally charged dullness. It is a simple, elegant, and brilliant solution. The second solution is the set of scene cards that give the players a single prompt to spur them in scene creation. The cards are gentle pushes to jumpstart the engines of the players’ imaginations while simultaneously creating a gentle story arc if the block keeps standing. Things build easily and get more intense, and of course the intensity is coupled with an increasingly rickety tower and the ever-growing danger of spoken words of dialogue as players are more hesitant to engage in in-character dialogue, since they can only do so when they are physically touching the tower. So how do you explain roleplaying in a game that doesn’t even use the word? How do you tell players what they can say and when they can say it? How do you explain freeform play and when bricks need to be pulled? Goddamn, but their solution is brilliant Each character sheet has a list of “moves.” Us experienced roleplayers will see that and think of moves like in Apocalypse World, but an experienced boardgame player will merely think of legal moves available to a player. Players are invited to describe what their character does and to describe the environment of the scene as much as they want without having to pull a brick. Twice per scene, they can describe their character touching the other character (once) and revealing something intimate about themselves to the other player (once). When they do so, then they have to pull a brick and mark their sheet. The lead touches and reveals things intentionally, while the follow touches and reveals things unintentionally. But twice per game, they can do the opposite touching once and revealing once intentionally instead of unintentionally and vice versa, again for the cost of a brick pull. It’s so simple to look at the sheet and see what you can do, and of course players know exactly the type of story being told, so they only need the slightest prompting. With 8 scenes, each player has the potential to pull 18 bricks in the game. Eventually either the tower falls, or the scenes run their course and the game ends with the tower still standing. The epilogue happens when either of those conditions are met, and the prompt for the epilogue is determined by the number of bricks pulled during the game. The number of bricks pulled is called the “attraction score.” If less than 10 bricks are pulled, “you reveal too much, too soon, and the connection is irrevocably broken.” 11-13 bricks mean that “Passion burns bright, but fizzes quickly.” 14-16 results in “An uneasy intimacy.” 17-19 prompts the players to narrate a “Sweet, cherished love, with the bitter certainty of loss.” If you reach 20 or more bricks between the two of you, then the game suggests your passions have simmered long enough, cooked to proper piquancy, and “From now on, you only need each other.” I found the epilogue to be an interesting collection of options. They make a statement about passion and sexual tension so that the game itself makes that statement. There is a proposed relationship between passion and its constraint, and by the options available, either you are destined to be together forever or you are doomed to love lost. I find the 17-19 option especially interesting since the prompt doesn’t suggest possible loss, but certain loss. That certainty colors the interpretation of the 14-16 result, suggesting the uneasy intimacy is doomed; the characters just don’t know it. In short, the game is eager to set up a poignant story of heartbreak and has a generally pessimistic opinion of love rooted in sexual attraction. It makes sense to some extent because the obstacles presented in play have to be significant, and they can’t just be washed away in the epilogue. If I had the intellectual determination and insight, I’d keep pulling about this epilogue chart to analyze what is actually being said by the game about constrained passion. The game is tightly designed providing players with all the tools they need while giving them no room to wander. By making every brick pull tied to touches and revelations, players are rewarded for taking their scenes as close to the edge as they can while their desire to succeed in their pull keeps their characters apart. But if you truly want the characters to have a happy ending, you want to keep them constrained for at least 20 pulls. It’s really a fantastic feat of game design.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed