|

Here’s a fact about me: I don’t much enjoy playing dungeon-crawling games. From 1977 to 1990, Dungeons & Dragons was about the only game that I played, and I had a great time doing so. But after I was introduced to Fiasco in 2015, I fell down the rabbit hole finding all the incredible indie RPGs that had been made since the turn of the century, and I haven’t had much interest in returning to D&D and all the fantasy games it inspired. Here’s another fact: I own and have read a ridiculously large number of OSR texts, especially for someone who doesn’t enjoy dungeon-crawling games. So many designers I admire in the indie scene have been excited by the developments in the OSR scene that I keep picking up recommended books to see the source of that excitement first hand. That’s how I came to Macchiato Monsters. A designer I was talking to was building his own system, and he mentioned that his leaping off point was Eric Nieudan’s text. I immediately ordered a printed copy from Lulu. Having read it, I can see why the designer was inspired. First, my usual caveats. I have not played the game, only read it, so value my opinions accordingly. To quickly talk about the physical book, I really like the feel of this slim 60-page. It’s flexible but durable with solid binding. The layout is interesting and the artwork is beautiful. My only complaint is that the print is rather small for my aging eyes. On my first read through, I vacillated between excitement at the possibilities of the game and boredom at the commonness of the game. On the one hand, this is a very traditional game. You make characters to go on an adventure. You fight or avoid monsters, get treasure, die or thrive, and eventually purchase property or a business. You have the standard six stats introduced by D&D and use them to answer questions of success or failure while a GM makes the calls about what stat to use and whether you have advantage or disadvantage. In the usual OSR mode, character mortality is dangerous high, and characters are warned away from fighting unless it’s absolutely necessary. All the same, in the section titled “Fights, and how to avoid them,” there is combat information but no actual mechanics for avoiding fights. It is in all these ways and at those moments of reading the rules that I felt uninterested in how the game worked. What I found thrilling, however, is all the creative and suggestive content in the tables throughout the book. Character creation is really cool. In addition to your six stats, you give yourself a “trait,” which is just a descriptive word or phrase about who you are, what you do, what you have, or where you come from. Here’s where you can create your race or species, class or specialty. Just pick a word, and when that trait is relevant in a roll, you roll with advantage. Character creation is not only quick and easy, but it allows you an impressive range of character types in an easy and elegant manner. But for me, the thing that really shined, is the way you determine your starting equipment. There are 8 tables of 20 elements each. You role a d4, d6, d8, d10, d12, and a d20 each and those six results are your pickable options from the tables. The items get more powerful, useful, and effective the higher you go, of course. Let me give you some examples though, because the lists are a fantastic collection of narrative possibilities. Bread and ham, ragged cloth bag, sock filled with pebbles. Those details like the bounty letter, the sock filled with pebbles, the tarot cards, the loaded dice—they all suggest a past or an interest, and they turn this would-be hero into something interesting. One of the tables at character creation is “Heirlooms & Heritage.” Here are some entries for it: A shiny button, handed down from one generation to the next. All of these entries have the potential to provide rich context for your character as well as possible plot hooks and clues to who they are and why they are adventuring in the first place. One of the suggestions in the game is to roll up your equipment first and then build your character, which is precisely how I would do it because those items all point to a character that you might never have thought to create. The tables are all top-notch. There are a number of table for figuring out what monsters or NPCs are doing when players encounter them, what they want, and how they’ll react to the PCs. There’s a table for hirelings and their abilities, which suggest whole storylines in themselves. There’s a table for what could happen while you are camping. A sampling: Scouts. Monsters or troops are spotted in the area. Just passing through? You can see that each of these possibilities could launch whole storylines. The book ends with pages of random tables to creating plot hooks, items, NPCs, monsters, warring factions, and random locales. Each option is brimming with ideas and possibilities. These final tables are in a format I have never scene in which a magnificent range of information is generated by a single d6 and a single d8. So even just reading the book filled me with excitement and fantasies about what stories could be launched by all these disparate elements. This excitement, however, kept running into the ho-hum resolution system that was about doing tasks, defeating enemies, and working to make your dude stronger or more efficient. As Nieudan says on his opening page, play is about the “player intelligence,” “resource management,” and “deadly fights.” These narratively rich materials are mere color for what the core of play is about. The tension between these two things is perhaps most clearly seen in the way XP works: Characters level up after reaching a number of goals equal to their next level. For instance, a third level character needs to accomplish four goals to get their fourth level. That first sentence had me ready to play the game. Yes, you have all these narrative hooks, and the players can decide what they want to accomplish! But then that following paragraph makes clear that the goals are plot focused; they are what the adventure is about. And in case you didn’t get the meaning of that second paragraph, there is a boxed text to clear things up: Character goals. To allow for some character driven action, you may let each player have a goal that is unique to them. I would not allow more than one of these active at any time. Only one goal can be reached during a given session. Character goals, the stuff I thought it was about, is a carrot thrown to the players, one thing you can work on while you follow the mission at hand. It sucked all the air out of the text for me. That said, this is still one of the few games I would turn to to play a dungeon crawl game. I said that most of the in-play mechanics are unexciting, but there is one mechanic that I think is truly well done: the risk die. The risk die is a way to keep track of resources without ever being reduced to bean counting. Its mechanical core was undoubtedly picked up from the Black Hack’s usage die. The idea is that an item is given a die size, and whenever that item is used, you roll that die. On a 1 or a 2, then you reduce the die by one size. Whenever you roll a 1-2 on a d4, that signals that you have run out of the item. Nieudan changes it slightly by making the reduction happen on a 1-3 instead of a 1-2. But the true innovation I see here is that he applies the concept of the usage die to risky situations, creating what is effectively a clock that winds down at unexpected rates. So, for example, your encounter table for a certain area can be assigned a risk die, with d12 suggesting a safer environment and d6 suggesting a more dangerous environment. That encounter table has less harmful and even advantageous encounters at the top of the table and more dangerous and troublesome counters at the bottom. As the die is stepped down, the encounters are guaranteed to become more and more difficult. Once you roll a 1-3 on the d4, some significant and troublesome event happens and the die resets to its original size. This simple mechanic creates rhythms and escalations effortlessly and unpredictably. I’m really glad I picked up and read this book. There are a lot of ideas it inspired in me that I think I’ll be chasing idly for some time. And I’ll be returning to these tables a lot, I suspect, as a model for capturing big possibilities in limited details.

0 Comments

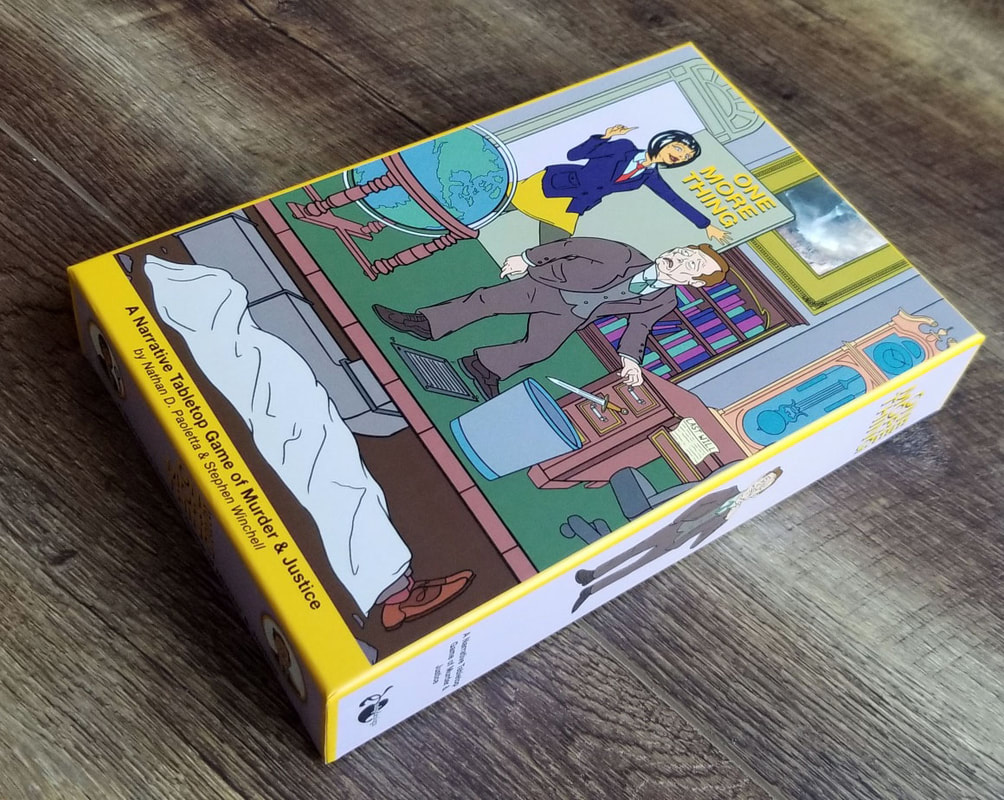

One More Thing is a short two-player storytelling RPG by Nathan Paoletta. One player takes on the role of the Detective, and the other the role of the Murderer. The story that play produces is supposed to mimic TV detective stories like you would see in an episode of Columbo or Murder She Wrote or The Rockford Files. As such, it is a foregone conclusion that the Detective will solve the crime and the Murderer will be brought to justice, so play is not about whether or not that will happen. Instead, “[y]ou play to find out how the Detective builds their case, how the Murderer reacts, and how the audience feels about the Murderer in the end” (from One More Thing’s rulebook, page 2). There are essentially two modes of play. The game comes with 5 pre-conceived murders with specific Detective and Murderer characters. For a no-prep game, players can pick up their respective pamphlets, gather up the included clue cards, and start playing. The other mode is to create your own characters and unique murder to play out, creating your own clue cards at the beginning of play. Play time ranges between 1 or 2 hours, according to the box. This is where I give my ever-important statement that I have not played this game or seen it played. I am talking about and reacting to the written and packaged material in the boxed game, so take my opinion for what it’s worth. I backed One More Thing because, first, I trust Paoletta as a game designer, and second, because I’m always interested in ways designers make investigative games. When the game arrived in the mail last week, I had every intention to read the rules right away in anticipation of playing the game that evening with my wife, Ann. But as I read through the rules, I found my enthusiasm waning. It waned not because of any fault of the game, but because it wasn’t asking questions that were of great interest to me, and because it isn’t designed to surprise the players in the ways I was excited to be surprised. Both players know how the murder happened and who was involved. In the case of pre-constructed play, the information is shared between players at the outset. In the case of creating your own murder, the players work out the details together. Each player then takes turns describing a scene for their character, choosing a scene type from a list of 4 types. The player chooses the scene type by deciding either what they would like to see in the fiction or what they would like to accomplish in terms of the game played on the board. The board is a 10” square that sits between the players with a basic grid on it. Along the bottom, the grid tracks how much evidence has been entered into play, and along the Y-axis, the grid tracks how much sympathy the killer has from the imagined viewing audience. Both axes run from 1-6. So your character can be unsympathetic and careful to leave behind only a few clues, sympathetic and careless with the evidence they leave behind, or anywhere in between on either axis. The evidence that enters the fiction can exist in three different states. If they are in the clue card pile, then the evidence hasn’t yet entered into the fiction. A card can then be turned over and placed in front of the detective. At that point, the evidence has clue the fiction, but the detective has not yet interpreted the clue for the audience to tell us why it is important. Once it has entered the fiction, the detective can use a turn to enter it into evidence, which means that they have interpreted the clue to indicat how it implicates the murderer. Once the clue has been entered into evidence, the marker tracks up the X-axis. Each scene type available to each player has a range of possible outcomes. The murderer’s sympathetic standing can rise and fall, clues can be found, and clues can be entered into evidence or removed as evidence. As the murderer you can try to control how sympathetic your character appears, or you can choose not to. As the detective, you can choose how you want to enter clues into evidence to tighten the screws on the murder. As long as there are a minimum of two clues that have been entered into evidence, either player can call for a final scene in which the characters confront each other and the detective lays out the evidence to get the murderer to confess. Like the good designer he is, Paoletta knows precisely where the play happens in his game, and he constructs One More Thing carefully to allow for one set of possibilities and to exclude others. As I stated earlier, my problem with the game is not the design but with my lack of interest in where the play happens. A lot of the scenes are set up to be either descriptive only or with limited roleplaying, and within that roleplaying there is little room for narrative surprises. The cat and mouse game can only explore so much when the mouse can never actually get away and in fact has to want to be (or at least resign themselves to being) caught. It’s tricky to structure play within tight confines. To do so is to bank on targeting the right part of play. Paoletta uses similar restrictions in his recently-released RPG Imp of the Perverse. In that game, it is similarly guaranteed that the monster hunters will identify and defeat the monster wreaking havoc in the game world. That particular restriction I don’t have any problem with because I think the question it poses through those limitations is an interesting one: what is your character willing to do to achieve that end? That’s an interesting question and gets at the heart of why I play many of the RPGs I play. I want to know who these characters are. Not just who they think they are or who they tell themselves they are, but who they are as revealed by the decisions they make. In much of One More Thing, the characters main decisions happen before play, revealed in why the murderer murdered and why and how the detective investigates. Undoubtedly how the murderer responds to the detective on their trail will tell us something, but it feels to me like small potatoes. Maybe in play, I’d be delightfully surprised how it actually unfolds, but I can’t really see it from here and the possibility doesn’t seem great enough to want to put aside other evening activities to give it a whirl. I see a lot of game designers fascinated with genre and emulating genre conventions in their game design to, of course, mixed results. It’s an interesting question what you choose to leave open to be revealed through play and what gates you seal off to channel play in your desired directions. Here, the genre convention of the detective outsmarting and catching the murderer is a severe restriction. I can see that the issue of sympathy was included to give the murderer player something to shoot for or care about in the decisions they make during play, but it’s not a particularly riveting question, especially since it doesn’t matter in any sense. Sometimes a sympathetic murderer is just what you want, and sometimes a murderer with few redeeming qualities are the thing. I often think about a blog post of Vincent Baker’s from “anyway” called “Conflict Resolution sans Stakes.” Here’s the lengthy passage that I keep running over in my mind: So Bruce Willis' character, this woman, and these bad-ass villains, right, and it's you, me and Mitch playing a roleplaying game. We've got a bowlful of dice on the table. The question confronting us, right now and urgently, is: can the villains win? Can they really beat Bruce Willis' character at investigation, deception and violence? If they can, it makes sense to roll dice for them. If they can't, it doesn't. So can they? There is value in games that have the room to live both within a larger genre while defying narrower classifications. In the case of these three Bruce Willis films, you don’t know which type of story you’re telling until the game is over and the dust has settled. The elements of randomness and bounce as well as the range of possible responses by the players keeps things up in the air and full of possibility, which naturally breathes life into play. Now just because I love this aspect of roleplaying doesn’t mean that every game needs to provide that possibility—I’m not trying to be prescriptivist about this. I find that very few games can be reduced as tightly as One More Thing while still allowing enough breathing room for excitement. The rulebook breaks up the two ways to play the game, so when I found myself disappointed by the pre-constructed way to play, I hurried on to the build-your-own murder play. I love the simple tables and tools Paoletta gives you to construct your murderer and murder; it’s a tool I plan on using liberally in my other roleplaying. But once the murder has been created, both players come up with clues and everything is known, for the most part. All the creative play happens before the game itself happens, at which point you are in a simulated writer’s room to see how to tell the tale of how this murderer gets caught by this detective. It would be at the point that play is set to begin that I least care to play it forward to see what happens. Obviously the game has given me a lot to think about, and for that I am grateful. I have no regrets about backing the game. The pieces of the physical game, from the box to the board to the character sheets to the tokens are all top notch, so if this game excites you, it is well worth getting the physical set, which Paoletta now sells on his website, www.ndpdesign.com. I don’t remember where in my readings I first became aware of Ganakagok. I found this copy, from the 2006 publication of the game, labeled as the “Second Edition”, on ebay for a reasonable price. It has sat on my shelf for two years now, and something brought it to mind, so I pulled it out and gave it the read it deserves. There is a more recent version of the game available as a PDF at Indie Press Revolution and all downloads are at ganakagok.com. I haven’t read the most recent version, so I don’t know what rules might have been changed, added, or removed. As usual, let me preface my thoughts here by noting that I have not played the game, so take my thoughts for what they are worth. I have read the book through twice and played it out in my head, but not everything works at the table the way it does in my head, and certain interactions between parts of the game might not occur to me. The basic idea of the game is that you are exploring the fantastic lives of a handful of the inhabitants of Ganakagok in a time of change. Ganakagok is a giant iceberg that has been wrought by some ancient force to have spires and caves and numerous mysteries. The people who live on Ganakagok are called the Nitu and are a quasi-Inuit people. Ganakagok and the Nitu have always existed in a permanent night under a sky of spinning stars. But now dawn is coming, and players play to find out what will become of these specific characters, the Nitu people as a whole, and Ganakagok itself when the dawn arrives. The main unique element in the game is a deck of custom-made tarot cards, which the game calls the Ganakagok Tarot. It’s a 52-card deck made of 4 suits with 13 cards in each suit, just like a regular deck of playing cards. The four suits are Tears, Flames, Storms, and Stars, and the cards run from 2 to 10, the face cards being the child, the man, the woman, and the Ancient. Each card has the following information on it:

The tarot is not a gimmick within the game. It is the main feature in just about every aspect of play, from character and world creation to scene setting to scene resolution. All this information on the cards allows for a range of inspiration for and interpretations by the players. The information also guides the tone and theme of the game by constantly having the language, imagery, and mythological structures of the world before the players. It’s not just a cool device; it is put to excellent use in the game. Ganakagok is designed for short-term play. To this end, White put in a pacing mechanic that ushers players through the stages of the game, though players are given some control over how quickly they move through those stages. At the outset of the game, the GM lays out 4 cards from the tarot, each representing one of the 4 spiritual powers that rule the Nitu people’s world: The Stars, The Sun, The Ancient Ones, and the Ancestors. The cards are kept face down before the players, but the GM uses the information on the card to determine the general length of the 4 stages of the game: Night, Twilight, Dawn, and Morning. As players have their scenes, they can put points into the current stage, and when those points meet the threshold determined by those 4 opening cards, the game shifts to the next stage. Before going on to the next stage, one of the 4 face down cards is revealed, and the player who revealed it, uses it to divine something about the role of the spirit in the great change that is happening. In other words, we learn at that moment what the Stars want to happen, why the Ancient Ones build Ganakagok, what the sun intends to do—or whatever questions the players want answered at that time. It’s a neat way to have the mystery about what is happening revealed slowly and organically, with each revelation potentially influencing the scenes and play that follow. There is no pre-planning required, and that creative burden is spread among the players. It’s a simple, neat, and effective system. Finally, when Morning arrives, the game ends, and there are mechanics to determine the final fate of the players’ characters, the Nitu people, and Ganakagok itself. Characters are tied directly into this big change. Character creation begins with three cards from the deck, which players interpret to decide 1) how they know the great change is coming, 2) what they hope the great change will bring or prevent, and 3) what they fear the great change will prevent or usher in. This is the starting point for learning who your character is, and everything else stems from it. Those cards also tell you what “good medicine” and “bad medicine” your character begins play with. Medicine can be spent at this point to build your character and the world. Good medicine can give you important items, relationships, knowledge, and access to the spirits, while bad medicine gives you limitations, fears, troubled relationships, and sins that weigh on your soul. By the end of character creation, you have your character positioned in relation to the oncoming change, to the other PCs, to the village you are all a part of, and to the landscape. Additionally, a loose map has been constructed and a basic relationship web within the village are constructed through this process. As play continues, the maps (physical and relationship) will be added to and changed. I really like the character creation process. Like a lot of Forge games of this period, Ganakagok relies on point systems to “buy” facts and details of the world and your character, which I have not traditionally been a fan of, but here the point system is both simple and meaningful. Yeah, the same thing could be accomplished without points, but because the points tie into the cards and because there is a simple way to adjust those points while you build your character, I think it works well here. So character creation positions your character and the world as it exists in the Night, the status quo before the world begins to change. As play begins, 4 more tarot cards are flipped and interpreted to answer the questions “What is happening in Ganakagok right now?” and “What is happening in the village right now?” This begins to upset the status quo and gives the players something immediate to respond to on their turns. From that point on, scenes are meant to bring situations of change and choice as the normal relationships and routines are upset. Game play is turn-based, and during your turn, you let the GM know what your character is doing or wants to do, creating a quick sketch of a scene. The GM then flips a card from the tarot deck and interprets it to create a situation that is designed to become untenable. You play out the scene until you can identify what White calls the “fateful moment,” the decision or action whose outcome will have meaningful ramifications. He’s careful to separate fateful moments from conflict. Sometimes those two are the same thing, but to resolve a fateful moment is not to resolve the central conflict in the scene. Resolving fateful moments is the most involved part of play as it involves cards, stats, dice, manipulation of those dice by spending points on your character sheet created by the good and bad medicine you spent earlier, and a process for determining narration rights. It all hangs together, but the process is rather involved. I like that all players can be involved in the process, not just the player whose character is involved in the fateful moment. I also like that the event is resolved in two stages that lets the fateful moment arise, take steps toward a resolution, meet a whole bunch of influences to push the resolution toward individually desired outcomes, and then have a final resolution. The staging of the process is cool, and if played well, it can lead to all kinds of cool narrative details that turn the fateful moment into a capital-E event. But there is nothing to require that kind of connection between the points and fiction, so I imagine some play can devolve into point spending without the narrative build. I can also see all the point-shifting that happens being a potentially annoying back and forth that detracts from the excitement rather than builds on it. That whole back and forth relies on a somewhat adversarial relationship between the GM and the players, the players using their good medicine to help their own cause and the GM using their fiat points to create complications. This is always a difficult line to walk because the GM is given no motivation other than being an adversary, creating complications for complications’ sake. It requires a GM with a good sense of when and where to put pressure and when to say its enough. The game provides its own limitations by dictating how many points the GM has to spend, but the randomness of it all means that the GM may have too many or not enough points at time, preventing a potentially powerful scene from reaching its promise or building up a scene that is better left alone. Good and experienced players might never have a problem, but we can’t all be good and experienced all the time. It’s unclear by the rulebook if the GM is supposed to go as hard as they can whenever they can, or if they are playing to some other purpose. Clarifying that purpose (both in the rules and through the mechanics) would go a long way to alleviating this potential problem. A scene resolves with a pool of points for one of the players to spend, which they can use to 1) improve their own character or their situation, 2) help out another character, 3) advance the stage clock toward entering the next stage, 4) shore up points for a positive or negative ending for the villagers, or 5) shore up positive or negative ending for Ganakagok. Sometimes the player will have a lot of points to spend, and sometimes they many only have one point to spend. This is the part of play it’s hardest for me to imagine in action, since those are a lot of choices with probably only a few points to go around. On the one hand, I like that you have to chose between benefiting yourself now or your people in the long term, and I like that you can control whether the clock advances or now, letting you speed up or slow down the overall game. On the other hand, that has to feel like a Sophie’s Choice sometimes which I imagine often leaves the player dissatisfied. That means the tough decision is good, but the dissatisfied feeling is not. The text itself is good. There are a lot of visual aids and examples, which I appreciate. The rules themselves, however, are difficult to follow as presented. I read the book through twice not just to make sure I understood but to understand at all. There are a lot of moving pieces and the way that a mechanic acts and interacts are not all explained in one place. The good news is that they are all explained, and it all makes sense. I didn’t end my second reading with any questions about how the game worked. The only bad news is that it was work to get to that understanding. I imagine that much of the most recent edition is about making the game easier to understand and grasp on an initial reading. There’s a lot about the game that’s exciting and that I’m eager to see in play. I’m especially excited to see the tarot cards in action and to go through character construction. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed