|

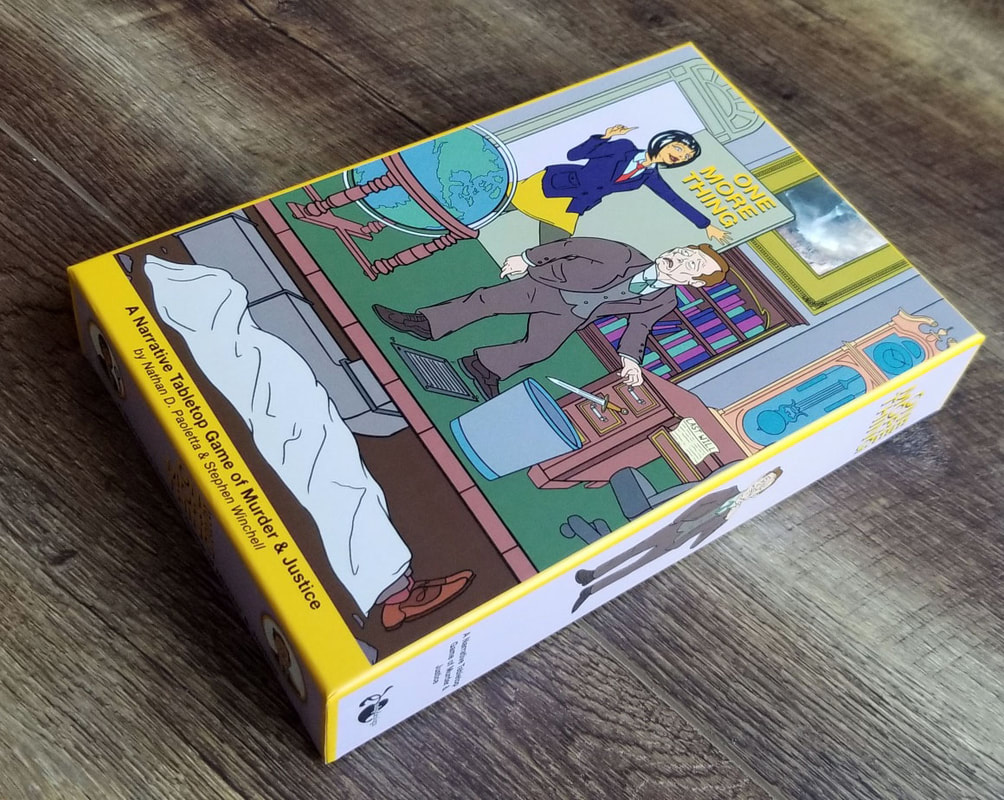

One More Thing is a short two-player storytelling RPG by Nathan Paoletta. One player takes on the role of the Detective, and the other the role of the Murderer. The story that play produces is supposed to mimic TV detective stories like you would see in an episode of Columbo or Murder She Wrote or The Rockford Files. As such, it is a foregone conclusion that the Detective will solve the crime and the Murderer will be brought to justice, so play is not about whether or not that will happen. Instead, “[y]ou play to find out how the Detective builds their case, how the Murderer reacts, and how the audience feels about the Murderer in the end” (from One More Thing’s rulebook, page 2). There are essentially two modes of play. The game comes with 5 pre-conceived murders with specific Detective and Murderer characters. For a no-prep game, players can pick up their respective pamphlets, gather up the included clue cards, and start playing. The other mode is to create your own characters and unique murder to play out, creating your own clue cards at the beginning of play. Play time ranges between 1 or 2 hours, according to the box. This is where I give my ever-important statement that I have not played this game or seen it played. I am talking about and reacting to the written and packaged material in the boxed game, so take my opinion for what it’s worth. I backed One More Thing because, first, I trust Paoletta as a game designer, and second, because I’m always interested in ways designers make investigative games. When the game arrived in the mail last week, I had every intention to read the rules right away in anticipation of playing the game that evening with my wife, Ann. But as I read through the rules, I found my enthusiasm waning. It waned not because of any fault of the game, but because it wasn’t asking questions that were of great interest to me, and because it isn’t designed to surprise the players in the ways I was excited to be surprised. Both players know how the murder happened and who was involved. In the case of pre-constructed play, the information is shared between players at the outset. In the case of creating your own murder, the players work out the details together. Each player then takes turns describing a scene for their character, choosing a scene type from a list of 4 types. The player chooses the scene type by deciding either what they would like to see in the fiction or what they would like to accomplish in terms of the game played on the board. The board is a 10” square that sits between the players with a basic grid on it. Along the bottom, the grid tracks how much evidence has been entered into play, and along the Y-axis, the grid tracks how much sympathy the killer has from the imagined viewing audience. Both axes run from 1-6. So your character can be unsympathetic and careful to leave behind only a few clues, sympathetic and careless with the evidence they leave behind, or anywhere in between on either axis. The evidence that enters the fiction can exist in three different states. If they are in the clue card pile, then the evidence hasn’t yet entered into the fiction. A card can then be turned over and placed in front of the detective. At that point, the evidence has clue the fiction, but the detective has not yet interpreted the clue for the audience to tell us why it is important. Once it has entered the fiction, the detective can use a turn to enter it into evidence, which means that they have interpreted the clue to indicat how it implicates the murderer. Once the clue has been entered into evidence, the marker tracks up the X-axis. Each scene type available to each player has a range of possible outcomes. The murderer’s sympathetic standing can rise and fall, clues can be found, and clues can be entered into evidence or removed as evidence. As the murderer you can try to control how sympathetic your character appears, or you can choose not to. As the detective, you can choose how you want to enter clues into evidence to tighten the screws on the murder. As long as there are a minimum of two clues that have been entered into evidence, either player can call for a final scene in which the characters confront each other and the detective lays out the evidence to get the murderer to confess. Like the good designer he is, Paoletta knows precisely where the play happens in his game, and he constructs One More Thing carefully to allow for one set of possibilities and to exclude others. As I stated earlier, my problem with the game is not the design but with my lack of interest in where the play happens. A lot of the scenes are set up to be either descriptive only or with limited roleplaying, and within that roleplaying there is little room for narrative surprises. The cat and mouse game can only explore so much when the mouse can never actually get away and in fact has to want to be (or at least resign themselves to being) caught. It’s tricky to structure play within tight confines. To do so is to bank on targeting the right part of play. Paoletta uses similar restrictions in his recently-released RPG Imp of the Perverse. In that game, it is similarly guaranteed that the monster hunters will identify and defeat the monster wreaking havoc in the game world. That particular restriction I don’t have any problem with because I think the question it poses through those limitations is an interesting one: what is your character willing to do to achieve that end? That’s an interesting question and gets at the heart of why I play many of the RPGs I play. I want to know who these characters are. Not just who they think they are or who they tell themselves they are, but who they are as revealed by the decisions they make. In much of One More Thing, the characters main decisions happen before play, revealed in why the murderer murdered and why and how the detective investigates. Undoubtedly how the murderer responds to the detective on their trail will tell us something, but it feels to me like small potatoes. Maybe in play, I’d be delightfully surprised how it actually unfolds, but I can’t really see it from here and the possibility doesn’t seem great enough to want to put aside other evening activities to give it a whirl. I see a lot of game designers fascinated with genre and emulating genre conventions in their game design to, of course, mixed results. It’s an interesting question what you choose to leave open to be revealed through play and what gates you seal off to channel play in your desired directions. Here, the genre convention of the detective outsmarting and catching the murderer is a severe restriction. I can see that the issue of sympathy was included to give the murderer player something to shoot for or care about in the decisions they make during play, but it’s not a particularly riveting question, especially since it doesn’t matter in any sense. Sometimes a sympathetic murderer is just what you want, and sometimes a murderer with few redeeming qualities are the thing. I often think about a blog post of Vincent Baker’s from “anyway” called “Conflict Resolution sans Stakes.” Here’s the lengthy passage that I keep running over in my mind: So Bruce Willis' character, this woman, and these bad-ass villains, right, and it's you, me and Mitch playing a roleplaying game. We've got a bowlful of dice on the table. The question confronting us, right now and urgently, is: can the villains win? Can they really beat Bruce Willis' character at investigation, deception and violence? If they can, it makes sense to roll dice for them. If they can't, it doesn't. So can they? There is value in games that have the room to live both within a larger genre while defying narrower classifications. In the case of these three Bruce Willis films, you don’t know which type of story you’re telling until the game is over and the dust has settled. The elements of randomness and bounce as well as the range of possible responses by the players keeps things up in the air and full of possibility, which naturally breathes life into play. Now just because I love this aspect of roleplaying doesn’t mean that every game needs to provide that possibility—I’m not trying to be prescriptivist about this. I find that very few games can be reduced as tightly as One More Thing while still allowing enough breathing room for excitement. The rulebook breaks up the two ways to play the game, so when I found myself disappointed by the pre-constructed way to play, I hurried on to the build-your-own murder play. I love the simple tables and tools Paoletta gives you to construct your murderer and murder; it’s a tool I plan on using liberally in my other roleplaying. But once the murder has been created, both players come up with clues and everything is known, for the most part. All the creative play happens before the game itself happens, at which point you are in a simulated writer’s room to see how to tell the tale of how this murderer gets caught by this detective. It would be at the point that play is set to begin that I least care to play it forward to see what happens. Obviously the game has given me a lot to think about, and for that I am grateful. I have no regrets about backing the game. The pieces of the physical game, from the box to the board to the character sheets to the tokens are all top notch, so if this game excites you, it is well worth getting the physical set, which Paoletta now sells on his website, www.ndpdesign.com.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed