|

I read the third edition of Matthijs Holter’s Archipelago, the one edited and laid out by Jason Morningstar. The game is a GMful storytelling RPG designed to “capture the feeling of Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea books.”

There’s something pure in the simplicity and structure of Archipelago. Everything has its purpose and reduces the RPG elements to their most basic function in play. Every part of the game answers the question, how do a group of people harmoniously create a narrative that has direction, connections, surprises, and consistency, harnessing the creative power of everyone involved while negotiating their different visions and impulses to create something shared and appreciated by all. Character construction and world construction are about giving you what you need to create an interesting story. World construction begins with a genre and a map to put everyone on the same page. Then the players decide on what “elements” are central to the world and distribute ownership of those elements among the players so that everyone is in charge of one area. The act of deciding what elements are central to the story let’s everyone know what aspects of the world will be important to the story. Ownership exists “to make sure that the setting has integrity, that there is a uniting vision for these elements.” Additionally, five or more locations need to be named and established on the map to give players enough room to begin play while still leaving plenty to be discovered during play. Once the world is sketched out and its elements are agreed upon, characters can be created. It’s important to play that characters are created together and out loud so that ideas can be shared and that matters of tone and scope can grow organically through conversation. Each character needs to have what the game calls an “indirect relationship” with each of the other PCs. An indirect relationship simply means that our two characters have an important person, thing, or idea in common. Perhaps my father is your lover, or we both fought in the same famous battle but on opposite sides, or your sister wrote the book that is central to my cult. These relationships allow us to make whatever character excites us while still providing the groundwork for our stories to overlap and cross each other. Even if they manage not to overlap, our stories will exist in the same world and space, commenting and reflecting upon each other. Finally, each character needs to start the story in motion, so you give them a grand destiny or a driving concern. And that’s everything you need to get a story moving. The specific story you are going to tell is given direction through the use of destiny points. At the beginning of the session, after the world and characters have been created and the story is ready to commence, each player writes a “destiny point” for each of the other characters: “This is an event that will occur in the life of the character – something dramatic, significant, perhaps something that changes their life.” The player then selects one of the proposed destiny points and places it where all the other players can see. Having other players create proposed destiny points gets everyone thinking about everyone else’s characters and where they might be going. It means that as we play, I’ll have things in mind as I take on secondary characters or propose obstacles and scene details for you. In addition, having your destiny points created by the other players means that you can be surprised by the path your character is set to travel, while being able to pick the destiny point that appeals to you means that you buy in on the direction your story will go. This need to be surprised and not in full control of your character’s story is an important element of any diceless, GMful game. We see this same concern in the rules of the game that say you can never interpret your own fate or resolution cards. You get to choose who interprets the card, but not how it is interpreted or what happens to your character as a result of that interpretation. The fate cards are a collection of 12 narrative prompts that each player can turn to once per session in order to give their story some narrative juice. The resolution cards are a series of “yes, and” “yes, but” “no, and” “no but” and “perhaps” cards that can be used once per scene to decide how a character’s actions play out. The creative power of the game is in the minds of the players. The rules are constructed to tap into that power and negotiate the different impulses and desires to create something greater than any single mind would come up with, something enjoyed by all. The game employs six ritual phrases that create a shared language for the players to negotiate with the other players, allowing them to push for what they want. The phrases – “try a different way,” “describe that in detail,” “that might not be quite so easy,” “harder,” “help,” and “I’d like an interlude after that” – are strong enough to direct but too weak to control the conversation and developing narrative. You can push and pull at the story, but you can’t keep your hands on it and simply point it where you want it to go. The phrases mean that you can take chances knowing the other players can jump in if they don’t like where things are going. As a group, using the phrases, you can fine-tune your individual visions until they become a collective vision. Every rule has its place and its function. All the tools either create narrative and drive or negotiate the different visions and impulses at the table. There is nothing extraneous and nothing missing.

0 Comments

I was just about to select the next RPG for study when I got this in the mail!

I'll be reading Laura Simpson's new Companions' Tale for the next week or two (I'll be going slow because I have a huge work project I need to be doing), so if you got a copy yourself and want to read too, I'd love to hear your thoughts as I put together my own! Matthew Gwinn’s The Hour Between Dog and Wolf is an innovative 2-player RPG. One player plays a serial killer and the other plays the “hero” hunting the serial killer, be that a detective, medical examiner, psychic, or whatever. The game uses the word “hero,” but it is not interested in any idealized heroic figures. Inspired by films like Se7en and shows like Criminal Minds, the game seeks to create stories in which the core tension is the psychological unraveling that hangs over the hunter and the cat-and-mouse interplay between the killer and their pursuer.

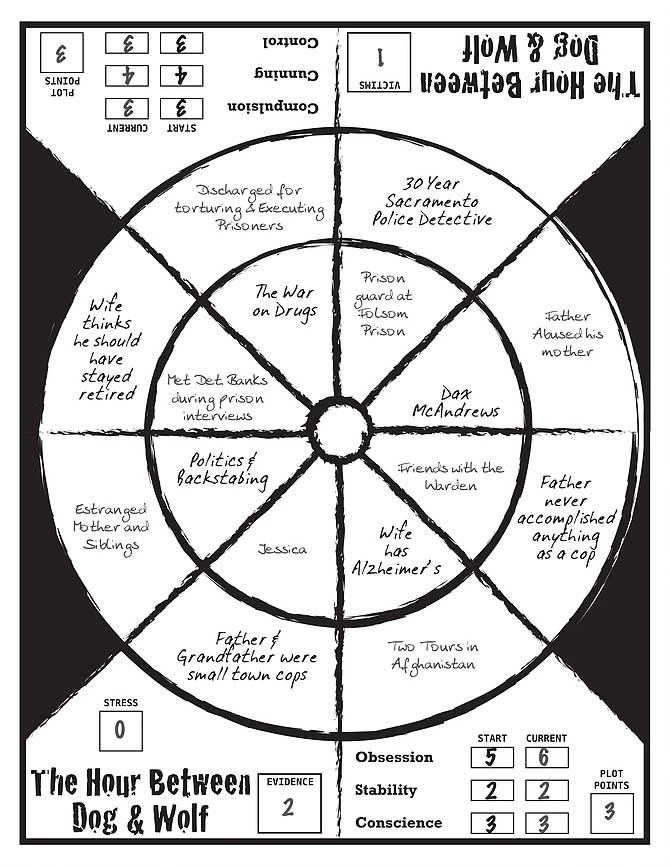

The rules themselves are fairly simple. Much of the 64-page rulebook is given over to character creation, specifically guidance for understanding and portraying your character. There are eight hero archetypes, and the book details how each investigates murders and what types of advantages and disadvantages their position and approach grants them. Even more useful – and more extensive – is the information the text provides for the killer player. To give the killer player the information they need to portray a serial killer with purpose and consistency, the text spends a long time categorizing serial killers: their methods, motivations, victims, hunting grounds, and manner of dumping bodies of past victims. Every bit of information is designed to help you make decisions about how to portray and imagine your killer. It’s time well spent. Without this guidance, players are in danger of either rehashing details from movies and books or flailing about trying to figure out what to describe next, probably both, which cuts into everybody’s fun. Beyond these fictional details, characters have a set of stats that go up and down throughout the game. The killer tracks their compulsion (the overwhelming drive to kill), cunning (the cleverness to stalk prey and avoid capture), and control (the need and ability to control and manipulate others). The hero’s stats are obsession (the overwhelming drive to catch the killer), stability (the strength of personal relationships), and conscience (the sense of morality and willingness to follow the law). In addition to these primary stats, the players track the hero’s stress (the toll taken on the hero’s mental wellbeing), the number of the killer’s victims known to the hero, and the amount of evidence collected against the killer. Once you have chosen your characters type, figured out the fictional details, and assigned stats, the final part of character creation is a cool process that links the characters with each other and maps out possible content for future scenes. Each player comes up with four aspects of their character or their lives that the player would like to explore through play. The players come up with those aspects together and share them so they both know what interests the other player. Then the players come up with and share four questions that they have about the other player’s character. Players can posit information in their questions, and in this way they help shape the characters and their relationships. For example, the killer player might pose the question, “Why are [the killer] and [the hero] friends?” or “Why is [the hero]’s relationship with her father so fraught?” So by the time you’re ready to play, you know who your character is, how they operate, what you want to learn about them through play, and what about them interests the other player. Relationships are pointed to, if not outright detailed. All you need is a murder to kick things off, which is how play itself begins. The killer player describes so aspect of the killing that begins the story. This is an opportunity for the players to agree upon the tone and level of detail that they will maintain throughout the game. If it’s going to be gory and graphic, now’s the time to establish it. If violence is going to take place mostly off screen and much of the horror veiled or alluded to, now’s the time to make that clear. By beginning with this description, the game allows this necessary conversation to occur naturally with something concrete. From here, the hero and killer take turns choosing from a list of scene types. Each scene type gives the player a chance to increase or decrease a specific stat - affecting either themselves or their opponent – by successfully achieving their goal for that scene. In this way, the killer can find themselves more compulsive or increasingly cunning, for example, and the hero can find themselves more obsessive or increasingly unstable. Over the course of the game, both characters will likely spiral out of control as they play to trigger the end game. The end game is triggered when the stats reveal that the hero has more evidence than the killer has cunning and control, or when they reveal that the killer has more victims than the hero has stability and conscience. No matter who “wins” both characters will likely find themselves in a desperate state, the hero having crossed questionable lines and sacrificed family and friends in their pursuit, the killer driven by a nearly uncontrollable compulsion to kill that will never bring the satisfaction they seek. Players choose scenes for their character depending on what stat they want to affect in order to get the ending they desire. The killer can either try to kill enough victims to outrun the hero’s stability and conscience, or the killer can try to win with a low victim count by chiseling away at the hero’s stability and conscience instead. The hero can try to gather enough evidence or instead try to undermine the killer’s cunning and control. Each scene type dictates who frames the scene and what stats are affected. The scene framer acts as the GM, controlling the whole world except for the other player’s character. The scene plays until the acting character reaches a critical point in trying to attain their goal for the scene. Each scene type pits one stat of the hero’s against a stat of the killer’s. Each player roles a number of dice equal to that stat’s ranking. The player with the highest single die wins. In this way, the players are always playing against each other even when only one of the characters appears in the scene. So for example, in a “crossing the line” scene, the hero is acting questionably (morally or legally) in hopes of gaining a two-point increase in evidence at the cost of one point of conscience. When the roll comes, the hero rolls their obsession trait against the killer’s control trait. If the killer wins, they get to increase their control and the hero’s obsession is knocked down a point. The main tool used to frame scenes is an 8X10 page called the Framing Table. At the center of the table is a target divided into three rings, with the outer two rings each divided into four parts, and the center ring a single, small ring. At the time of character creation, players write the aspects they want to explore during play into those rings, one aspect in each of the eight segments of the two outer rings. Then, when the players takes their turn, they roll a mixture of black and white dice. Of the dice that land in the target, the player locates the segment with the highest die and uses the aspect in that segment as the focus of exploration in that scene. Or not. The player has the option to ignore the dice roll and focus on whatever they want in the scene. I like the idea of the framing table in the abstract, but it seems a clumsy way to help the players find a focus in the scene. The dice can go anywhere, and the aspect might not be right for that point in the story. The rules invite you to ignore the results of the roll, which begs the question, why is it there at all? It would be much smoother to just invite the players to pick an aspect not yet examined in play and create a scene to explore it. In the end, the framing table is an idea that looks cool but that I expect causes as many problems as it solves in play itself. (Note: I haven’t yet played the game, so I’m not speaking from a position of experience on this point.) The text is clearly written, and the rules are thoroughly covered. Other than feeling that the hero archetypes should have been briefer. I felt no impatience with or confusion over the text. I was not a fan of the photographs that illustrate the text. They are well done, but they look cheap, like stills from a B-movie. The game provides great reference sheets, although I can’t find them for download online. Having a physical copy of the book, I’ll have to make photocopies from it. A minor inconvenience, but an unnecessary one, it seems to me. I am excited to get this game to the table and expect to do so soon. If any of my opinions or thoughts change after playing, I’ll add an amendment to this review. I didn't get to play much this year because business was booming - good for the pocket book, but bad for leisure time.

I played: - Monster of the Week (2 sessions, as MC) - Call of Cthulhu (1 session, as player) - Lady Blackbird (1 session, as GM) - Apocalypse World (4 sessions, as MC) - Mars Colony (1 session, as Perkins) - BFF (1 session) - The Final Girl (1 session) - Undying (2 sessions, as GM) I was able to do a lot more reading/studying than playing. I read/studied, in roughly this order: - Bubblegumshoe - The Watch - Mars Colony - Night Witches - Monsterhearts II - Follow - Bluebeard's Bride - Grey Ranks - Demihumans (drafts) - Steal Away Jordon - Poison'd - With Great Power (Master Edition) - With Great Power (Classic Edition) - Remember Tomorrow - Mobile Frame Zero: Firebrands - 7th Sea, 2e - Montsegur 1244 - Seco Creek Vigilante Committee - The Bloody-Handed Name of Bronze - The Burning Wheel - Undying - Fall of Magic - Mortal Coil - Everway - Sandman: Map of Halaal - DC Heroes - Star Crossed - Under Hollow Hill (playtest docs) - To Serve Her Wintry Hunger - Society of Dreamers - The Clay that Woke - Holmes's Dungeons & Dragons - Alienor - Hero Wars (including the Narrator's Book, Thunder Rebels, Barbarian Adventures, and Orlanth Is Dead) In addition, I read the four volumes of Designers & Dragons (The '70s, The '80s, The '90s, and The '00s). I post reviews of nearly everything I read on my Goodreads account, where you can find me as Jason D'Angelo, if you're interested (link to my profile page: https://www.goodreads.com/user/show/12127805-jason). The reviews are not always super detailed, and not even reliably proofread, as I don't let myself begin the next book until I have put my thoughts about the current book into writing. My current reading project is Matthew Gwinn's The Hour Between Dog and Wolf. Sartar Rising: Barbarian Adventures is the first setting and scenario campaign book for Hero Wars. When I ordered the book I was interest to see how scenarios were organized and presented. I was surprised to find that the first 2/3rds of the book is really setting information, discussing the tribal history of the Orlanthi, the geography of Dragon Pass, & the daily lives of the Orlanthi people. The information in the book dovetails with the information in Thunder Rebels, which is designed to be a companion piece. The text also points to Anaxial’s Roster and Storm Tribe.

The purpose for providing this extensive information about the daily and yearly lives of the Orlanthi people is that the designer wants you to spend the first part of your campaign experiencing normal life among the barbarians, going through the calendar and all its religious holy days. Rather than providing a set of scenarios, the book provides story seeds and starting points to locate where the dramatic possibilities are within the usual goings on. I found this unusual approach quite exciting because it is founded in discovery through play and the importance of community to who will one day be heroes of this world. The seeds pose problems and pressures for the narrator to present without any solution being required and pushed for. It is purely to see how the player’s react. Some seed ideas are “A priest complains that the leader has offended the gods,” “competition threatens a crucial trade relationship,” or this one: “Several sheep are found slaughtered in the fields. It was not outlaws or fugitives, because they are butchered the wrong way. It was not Telmori, because knives were used. It was not trolls, because there is some left. It must have been Lunars. They killed more than they needed, and a lot was left behind to feed foxes and flies. A Waste.” It is from these little incidences that the narrator can see what the characters care about and over what they will jump to action. Stringing a number of these event together, a larger picture of the world will come into focus, and it will all develop through play and discovery. It’s a surprisingly wide-open approach to campaign play and it made me want to play the game more than anything I’d read up to that point. There is a long game at play, which we learn in the second campaign book, Orlanth is Dead! That book, the same length as the first, has only one chapter with a single detailed scenario. That one scenario is the thing that launches the Hero Wars, the war for which the game is named. After the players have played through a normal year, Orlanth is Dead details half a year in which everything has gone awry, as the Lunars have apparently killed Orlanth himself. There is no wind and no magic for the worshippers of Orlanth. Little seeds again make up the bulk of play as villages go hungry and descend into panic and rebellion. It all leads up to the one scenario, which is nothing more than an extended battle sequence. But if you don’t know where this is going when you read the first Barbarian Adventures, it seems like a refreshingly odd take on a campaign. And once I understood what the game was doing, I appreciated the approach even more, because you could shape your world in any way you want over the last year and half of the calendar, as long as the Lunars weren’t defeated, and by keeping the scope so close to the local community, that couldn’t happen anyway. So by the time the “metaplot” arrives, the players have made Glorantha and Dragon Pass their own in ways that the metaplot doesn’t feel like it is decided from on high. Or at least that’s the goal, I think. By the time Sartar Rising: Barbarian Adventures was published in late 2001, Issaries seemed to have worked out all their bugs, because this is the most beautifully laid out of the texts and the best looking of them. The core book of Hero Wars has a lot of encouragement to make cool things up, like I pointed to in Kallai’s character description. The writers of the books know that Glorantha is a huge world with nearly 35 years (at the time the book as published in 2000) of imaginative construction. There is constant reassurance that you don’t need to know anything more than you do, that you can safely make up whatever you want and still follow along in the published campaigns.

I was initially quite jazzed by this encouragement to play fast and loose with Glorantha and Dragon Pass. But the more I read in the supplementary material the more that encouragement seemed like a lie. I mean, I know that it was genuine, but how are you supposed to make stuff up when so much of the world and culture has been defined? The game focuses on the Orlanthi barbarians of Dragon Pass. Most of the supplementary books focus on that one specific area and that one specific culture. The campaign material (as presented in the Sartar Rising books) assume that your players will all be Orlanthi barbarians. The one player’s book that was published in the first 3 years of the game’s release was about Orlanthi barbarians. And that’s cool! With a world as big as Glorantha, sticking to one particular area is helpful, especially to new players, yeah? The problem comes in when you start reading the first Sartar Rising book at the player’s book, Rebel Thunder. The society is not some loosey-goosey bunch of anarchists; this is a heavily structured and traditional society with strict gender norms, a class structure, and a convoluted religious mythology with a strict schedule of holy days. The seasons and calendar are unique, as are the crops grown and the attitudes toward certain ways of life. Holy shit, people! There is so little room to breathe once you get into the details of the society that I found myself quite claustrophobic. I realize you can punch holes in the fictional world and tear down whole walls, but everything is so entangled that it’s hard to anticipate what will be affected if you start dismantling things. The result is an uncomfortable tension between the language of freedom in the texts and the reality of the details of Glorantha. As a side note, focusing from the start on an oppressively patriarchal culture within Glorantha seems like a poor decision. A female character is either going to be a culture anomaly or a housewife with fighting skills. The authors assume that you will be playing a male character throughout all the texts, and the use of the he pronoun for the players feels like it goes beyond any conventional use. Not a single sample PC in all the examples within the book is a woman. It made me uncomfortable. If my wife tried to read the core book, it would have ended up thrown across the room before the third chapter. I know a lot of women who are fans of Glorantha, and I can’t imagine them loving these books. Sartar Rising, Volume II: Orlanth is Dead! is the second campaign setting and scenario book in the Hero Wars series. While it is the second book in the campaign, it is the first book with a specific, extended scenario. That scenario occurs only in the final chapter of the book. Before that, the book covers the important events that lead up to this moment. Because the scenario is an extended set of battles in a war, there is a whole chapter on military techniques of the different people involved in the way. There is also a cool “create your clan” worksheet that lets players answer questions together to decide what their clan’s past is and what they hold dear.

The scenario itself is all metaplot, and it is a good example of the limitations of metaplot structures. The story told is a large battle, the last stand of the Orlanthi against the Lunar forces. This is the first battle in the Hero Wars, and it’s the moment the Orlanthi are galvanized and united in rebellion. The battle’s end is predetermined: the Orlanthi will always win the battle no matter what the players do. In fact, every stage of the battle is predetermined and will have the same outcome regardless of the PCs’ actions. I can see that players could have a great time playing the scenario all the same, but as a GM, I’d have a hard time being invested in this scenario because in the end, it is designed to give information to the players, not probe the characters. There are no meaningful choices for them to make, no meaningful pressures to respond to. For example, at one point the text says, “This is no longer a battle, just a confused melee. Tell the heroes they can fight as long as they wish to. Use a d20 to determine the seemingly random AP opponents bid each round.” Oof, talk about taking the wind out of your sails. If I were running this scenario, I would want to work through the scenario to focus on personal matters important to the PCs, bringing to a head all the different pressures that were building up in the campaign up to this point so that the battle itself is merely a backdrop to the story the players are telling. I have not read the third book in the series, but I am intrigued to see where it goes and what the book focuses on. I imagine you can get a good couple dozen sessions between these first two books. I noted in my last Hero Wars post that characters in the game are simply a collection of ranked skills, traits, and qualities.

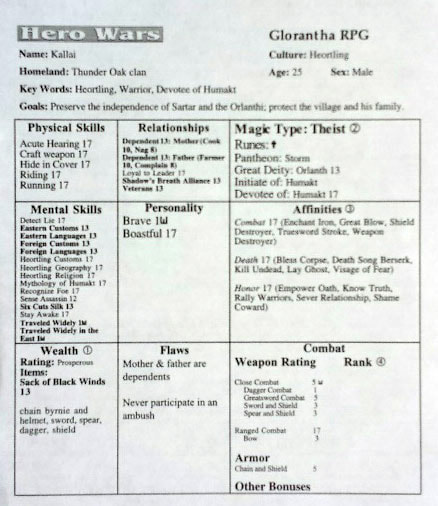

Some of those descriptive words and phrases come from the setting material. Your culture, your occupation, and your religion all give your character a set of standard keywords that everyone within those groupings will share. All Heortlings, for example, will have “Spear and Shield Fighting” and “Dragon Pass Geography.” All Lunar traders will have the ability to “Lie” and “Recognize Value.” Each deity has a group of affinities that every initiate knows and feats that every devotee knows. The core book comes with a chapter of these shared descriptors, called “keywords,” but that chapter covers only a few cultures, a few occupations within those cultures, and a few deities worshipped within that culture too. The plan was to release a set of player’s books for each culture which would be a full-scale overview of the culture for players, providing players with lists of common names, possible occupations, a list of the most common deities, and all the details of daily life and worship within that community. While Hero Wars was held by Issaries, only one such culture book was released, Rebel Thunder: Player’s Book for Orlanthi Barbarians. Another book, Storm Tribe: The Cults of Sartar gives a full overview of all the deities worshipped by the Orlanthi. It’s a pretty clever marketing idea since even just reading the core book I wanted to look at the other books to see what they covered and what the full range of possibilities were. It is of course every bit annoying as it is clever because while you can play with what you get in the core book, it’s easy to feel like you are missing a lot of good stuff if you don’t get the supplementary material as well. Beyond these keywords, the specific details are entirely up to you, and I do mean entirely. There are no set of words and descriptive phrases for you to choose from. Whatever words you want to use to describe your character you can use. In fact, there are two ways to begin character creation, and both involve just thinking about and describing who your character is. The first, and the coolest, way is to “write a 100-word description of your character” that includes your character’s name, her culture, her main goal in life, things your character can do, and anything special your character may possess. “The 100-word limit encourages you to keep your character simple and provides you with a challenge: The 100 words you choose will determine the capabilities of your character” (17-18) Here’s the example character from the book: “Kallai is a mercenary warrior, a devotee of Humakt. He has traveled widely and knows the languages and customs of many lands. Kallai went to the East and learned the secrets of the Six Cuts Silk. There he joined the Shadow’s Breath Alliance, swearing a blood oath of mutual protection to its members. Kallai owns the Sack of Black Winds, in which the Four Collapsing Words have been trapped since the War of the Straw Giants. Now he supports his aging parents and just wants to raise a family. Kallai’s chain Byrnie and equipment are in excellent shape.” And that’s where you begin. The game encourages you to make shit up, such as the Six Cuts Silk, the Shadow’s Breath Alliance, the Sack of the Black Winds, the Four Collapsing Words, and the War of the Straw Giants. Each of those elements are unknown even to the character’s creator, and were included with the intention of finding out what these things are through play. It’s a free-wheeling form of character creation, and very exciting. The player and narrator together turn that paragraph into a generous list of abilities, traits, and qualities on the character sheet and the player gives them each a ranking following the rules of the text. The other way to create a character is to just list 10 things about them, amounting to roughly the same thing. The only other game I’ve seen use this form of character creation is James V. West’s The Pool, in which players are given 50 words to create their character. (I am unaware who influenced whom or if there was no influence at all.) There are of course other games that use player-created descriptive words and phrases to define a character. Over the Edge was the first to do so (to my understanding), but there was also Everway, Sorcerer, and Fate. This method encourages players to be colorful and sometimes poetic, as the right word or phrase can communicate a ton of information. GMs have been known to be lenient with especially colorful descriptors. But if you don’t have that poetry in you, you will not be punished for an uninspired list, which means that this approach is artistically rewarding for those who want this kind of experience without punishing those who don’t. The biggest risk is that a player is self-conscious about their choices or that another player will try to be “helpful” by “improving” upon what you put together. Approaching this from the GM’s perspective, I especially like that NPCs and even deities and monsters are nothing more mechanically than a bundle of descriptive words and phrases. Even if you use uninspired language, each word you use to describe a character has weight because you can use each and every descriptor in some contest or another. So when a horse has “large 10W,” that immediately gets you thinking about how the horse can use its size to affect the world. Even negative traits are exciting to think about, as an NPC can have “Drone on about the Weather 20” or “Nitpick 13.” One villain could have “Taunt 15W,” another “Dueling 18,” and another “Strike without Warning 2W2,” and each descriptor comes with both flavor and actionability. The downside is that to make a fully-fleshed out NPC, you would have to include a ton of information, more than you can make up on the fly, but I imagine most GMs would quickly settle for 3-4 well-defined traits and then make up traits and ratings as they are needed during play. The core mechanic of Hero Wars is actually a beautiful thing, I think. There are several things that Laws needed or wanted the mechanic to achieve, and what he ended up with does a lot of work while still being surprisingly simple.

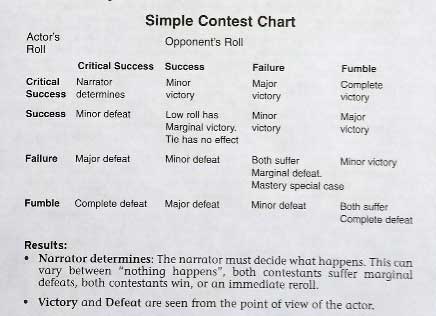

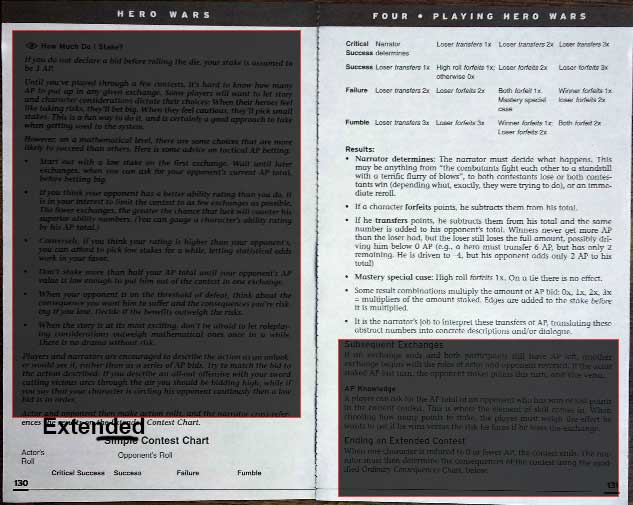

First, Laws wanted a single resolution system for every possible kind of conflict that could happen during play, from climbing a wall to seducing a guard to fighting a broo to performing a magic ritual. Second, the mechanic needed to scale skills, traits, and qualities to cover everything from the most common of commoners to literal gods. Third and finally, Laws wanted to have the roll involve a single d20 for each participant. I was surprised in reading Hero Wars how much I was reminded of DC Heroes in that Greg Gorden, the designer of DC Heroes also wanted a single resolution table for all possible types of conflict and needed to have a scale that would encompass everything from Jimmy Olsen to Superman. Laws and Gorden came up with different solutions, but there are certainly similarities, which I would love to tease out and analyze at some later time. Here are the set of mechanics that Laws developed from conflict resolution in Hero Wars: Whenever a character attempts to accomplish something, the dice will decide which of eight possible results come of that action. Those eight possible results are “complete victory,” “major victory,” “minor victory,” “marginal victory,” “marginal defeat,” “minor defeat,” “major defeat,” and “complete defeat.” The difference in degree determines how permanent and far-reaching the success or failure is. Characters consist of a list of skills, traits, and qualities, with each one of those things having a rating between 1 and 20. Whenever a character tries to accomplish something, they declare what they’re trying to do and what skill, trait, or quality they’re leaning on to get the thing done. The narrator (the name for the Hero Wars’s GM) can assign bonuses or penalties as she deems appropriate, adding the bonus to or subtracting the penalty from the ranking of the skill being used. The player then rolls a d20 and compares the result of the die to the number of the skill, trait, or quality (adjusted by any bonuses or penalties) being used. If the player rolls a one, the character had a “critical success.” If the player rolls a 20, the character “fumbled.” If the players rolls between a two and the adjusted rating number of the skill being used, the character has a “success,” and if the player rolls higher than the adjusted rating number and 19, the character has rolled a “failure.” Those categories – critical success, success, failure, and fumble – are not results in and of themselves. Depending on the type of conflict that’s taking place, those categories are then translated to line up with one of the eight possible results mentioned above. There are three basic kinds of conflict. 1) The “Ability Test” is for determining the results of a straightforward tasks with no opposition. In the case of an ability test, the player rolls against the rating of the skill, ability, or quality that is being tested. Critical success then means a complete victory, success is a minor victory, failure is a minor defeat, and a fumble is a complete defeat. 2) The “Simple Contest” is for determining the results of a straightforward task with opposition. This is the default test in the game as opposition can come from natural forces and inanimate objects as well as from active opposition. In this case, the opposing participants both roll and determine if they have a critical success, success, failure, or fumble and then look on a chart to find out what result those two rolls translate into. (I’ve included a picture of that table below.) 3) The “Extended Contest” is for determining the results of a dramatically important task with opposition. I’ll discuss extended contests in more detail in a moment. It is up to the narrator to decide what kind of contest is called for, and the narrator’s choice is mostly a matter of pacing. The narrator can reduce a whole battle to a simple contest, or can create a large scene of swimming against a current using the extended contest rules. So you can see that if every skill or quality has a rating, and every contest relies on using a rated attribute, then every action in the game can be used with these three different conflict rules. I’ve included a copy of the sample character from the book below. You can see that Kallai can use his acute hearing in one conflict, his close combat skill in another, his boastful personality in another, and his detect lie in still another. Any word or phrase that can be used to describe your character can be given a rating, so any word or phrase you use to describe your character can be the basis for a conflict. That’s how the game uses the same resolution mechanic to settle any kind of conflict. Before I get to extended contests let’s look at how the game manages scale. When the rating of a skill exceeds 20, the character gains a level of mastery in that skill. Instead of that skill’s rating going to 21, the rating goes to 1W (where “W” is the mastery rune symbol). Characters (and everything else) can have multiple levels of mastery as well. Two levels of mastery is noted like this, say: 10W2. Six levels of mastery looks like this: 15W6. When mastery is involved, the results of the player’s roll are bumped up one ranking per level of mastery, so that a fumble becomes a failure at one level of mastery, a success at two levels of master, and a critical success at three levels of mastery. However, when you and your opponent both have levels of mastery at play, the mastery cancels each other out one-for-one, so that two characters with opposing skills of four masteries each would roll as normal without any bumps, but if one character in the conflict has one level of mastery and another has three levels of mastery, then the first character rolls normally, and the second character receives two bumps to her roll. This way, a starting character has no chance against a god, which might have 6-10 levels of mastery, but as the character improves to become god-like in their heroic capabilities, their traits can rival even the mightiest beings in a fair fight. It’s a very clever way to scale powers without making one player roll 6d20 and have to add up all the results. Everything is simple and quick to calculate while still allowing for a robust resolution system. And it does it all without having to have a page of charts that are consulted and compared as in DC Heroes. So now lets look at extended conflicts. When the narrator wants to slow down a moment of conflict to make it a big deal, she calls for an extended conflict. In an extended conflict, the characters convert the rating of the skill used into AP, or action points. (DC Heroes also has APs, but they stand for “attribute points.) Each level of mastery adds 20 AP to your total, and followers and other factors can also affect your AP total. A character’s AP signifies their resources, determination, and positioning within the battle. In each round of the conflict, you bid so many APs (representing how much effort you are putting into that action, and how much you stand to gain or lose as a result), and the dice determine how you and your opponent’s APs are affected in that exchange. You might gain APs, steal APs from your opponent, lose APs, or give APs to your opponent. To determine what happens, you compare your dice results on a chart similar to the one used in simple contests (which I have also included a copy of below). I’m a big fan of mechanics that map out the beats of a conflict, like Dogs in the Vineyard’s where each action and counteraction is created narratively by the playing of the dice in your pool. Hero Wars’s extended conflict recreates this effect, and I find that exciting. I like that your bid of APs shows how much you are risking, how big an attack you are making, so you can engage at any level from making a test of your opponent’s strength to a desperate all-or-nothing attack. The weakness of this system is that the game provides not natural way to limit the numbers of exchanges in an extended conflict. If players are cautious and the dice are wonky, AP totals can go up and down indefinitely. Dogs in the Vineyard has a maximum number of exchanges by stint of your limited dice pool. Trollbabe, which has a similar mechanic_ forces every encounter to max out at three exchanges. Nothing in Hero Wars puts a cap on the extended conflict. Laws was of course aware of this weakness and advised in the Narrator Book for the narrator to solve the problem by making the narrator’s character act foolishly: “If an extended contest seems to be dragging on forever, with cautious contestants passing small stakes back and forth throughout a long succession of exchanges, throw caution to the wind and have your narrator character stake all his remaining APs on a final, climactic exchange” (7). That’s certainly a way to do it (and the way I would do it) but that seems clumsy at best. This rather elegant system deserves a much more elegant solution than that. Overall, I like the core mechanic of Hero Wars. It’s an impressive, flexible tool that allows for any kind of conflict at any scale. Through the course of reading the various books or just playing the game, it seems like the narrator can quickly pick up appropriate ratings for various challenges of all sorts. Except for the unsteady and unreliable end-point of extended conflicts, I’m a fan. In my reading project, I have thus far limited my reading to the main text of any game. For Hero Wars, I found myself getting and reading a number of the supplementary texts. I have read the main book, the Narrator’s Book, the first part of Glorantha: Introduction to the Hero Wars, the whole of Rebel Thunder: Player’s Book for Orlanthi Barbarians, a cursory glance at Storm Tribe: The Cults of Sartar and Anaxial’s Roster: Creatures of the Hero Wars, and a thorough reading of both Sartar Rising: Barbarian Adventures and Sartar Rising, Volume II: Orlanth is Dead, the first two campaign books for the game.

Yeah, I know. In part, I read the additional texts because the main rules are poorly organized and presented. In part, I wanted to read more because this is my first foray into the world of Glorantha, and I kept wondering if some of my difficulties in understanding the game were related to my ignorance about the fictional world. In part, I was intrigued by the way the books served different functions for players and GMs and I wanted to see if they worked together in reality the way they were conceived and presented in the main book. In part, I did so because all the texts were pretty cheap and easy to get a hold of. It has been an interesting deep dive, and I’ll probably spend a couple of posts discussing and summarizing how the game works. "There is no numerical reward for giving your character a flaw. Some players may wonder why they should bother. Your hero, like any protagonist of an adventure story, is going to face more than his share of obstacles and adversities. The narrator is going to make sure that your character gets into trouble. By listing a flaw, you get to select the type of trouble he'll be facing, at least part of the time."

- Robin Laws, Hero Wars, page 26 |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed