|

The core mechanic of Hero Wars is actually a beautiful thing, I think. There are several things that Laws needed or wanted the mechanic to achieve, and what he ended up with does a lot of work while still being surprisingly simple.

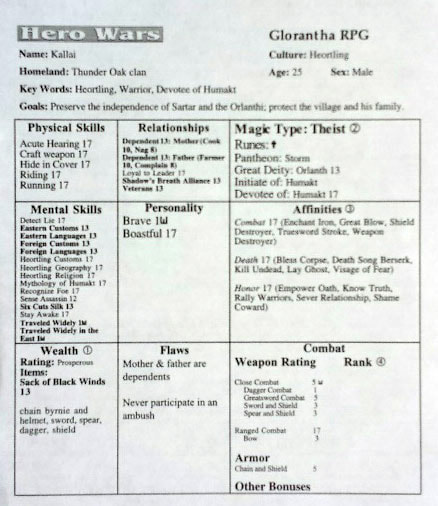

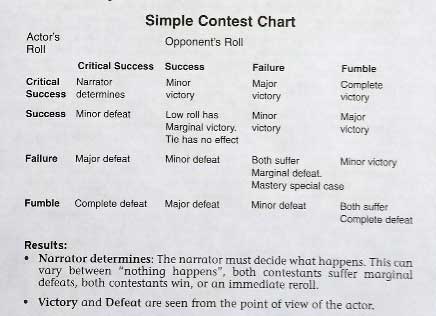

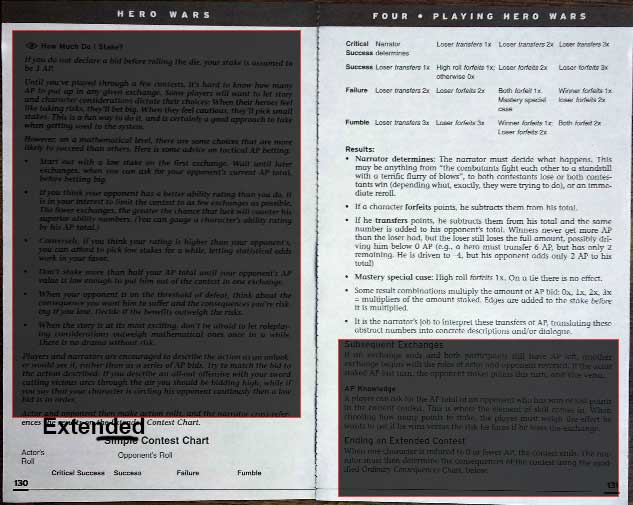

First, Laws wanted a single resolution system for every possible kind of conflict that could happen during play, from climbing a wall to seducing a guard to fighting a broo to performing a magic ritual. Second, the mechanic needed to scale skills, traits, and qualities to cover everything from the most common of commoners to literal gods. Third and finally, Laws wanted to have the roll involve a single d20 for each participant. I was surprised in reading Hero Wars how much I was reminded of DC Heroes in that Greg Gorden, the designer of DC Heroes also wanted a single resolution table for all possible types of conflict and needed to have a scale that would encompass everything from Jimmy Olsen to Superman. Laws and Gorden came up with different solutions, but there are certainly similarities, which I would love to tease out and analyze at some later time. Here are the set of mechanics that Laws developed from conflict resolution in Hero Wars: Whenever a character attempts to accomplish something, the dice will decide which of eight possible results come of that action. Those eight possible results are “complete victory,” “major victory,” “minor victory,” “marginal victory,” “marginal defeat,” “minor defeat,” “major defeat,” and “complete defeat.” The difference in degree determines how permanent and far-reaching the success or failure is. Characters consist of a list of skills, traits, and qualities, with each one of those things having a rating between 1 and 20. Whenever a character tries to accomplish something, they declare what they’re trying to do and what skill, trait, or quality they’re leaning on to get the thing done. The narrator (the name for the Hero Wars’s GM) can assign bonuses or penalties as she deems appropriate, adding the bonus to or subtracting the penalty from the ranking of the skill being used. The player then rolls a d20 and compares the result of the die to the number of the skill, trait, or quality (adjusted by any bonuses or penalties) being used. If the player rolls a one, the character had a “critical success.” If the player rolls a 20, the character “fumbled.” If the players rolls between a two and the adjusted rating number of the skill being used, the character has a “success,” and if the player rolls higher than the adjusted rating number and 19, the character has rolled a “failure.” Those categories – critical success, success, failure, and fumble – are not results in and of themselves. Depending on the type of conflict that’s taking place, those categories are then translated to line up with one of the eight possible results mentioned above. There are three basic kinds of conflict. 1) The “Ability Test” is for determining the results of a straightforward tasks with no opposition. In the case of an ability test, the player rolls against the rating of the skill, ability, or quality that is being tested. Critical success then means a complete victory, success is a minor victory, failure is a minor defeat, and a fumble is a complete defeat. 2) The “Simple Contest” is for determining the results of a straightforward task with opposition. This is the default test in the game as opposition can come from natural forces and inanimate objects as well as from active opposition. In this case, the opposing participants both roll and determine if they have a critical success, success, failure, or fumble and then look on a chart to find out what result those two rolls translate into. (I’ve included a picture of that table below.) 3) The “Extended Contest” is for determining the results of a dramatically important task with opposition. I’ll discuss extended contests in more detail in a moment. It is up to the narrator to decide what kind of contest is called for, and the narrator’s choice is mostly a matter of pacing. The narrator can reduce a whole battle to a simple contest, or can create a large scene of swimming against a current using the extended contest rules. So you can see that if every skill or quality has a rating, and every contest relies on using a rated attribute, then every action in the game can be used with these three different conflict rules. I’ve included a copy of the sample character from the book below. You can see that Kallai can use his acute hearing in one conflict, his close combat skill in another, his boastful personality in another, and his detect lie in still another. Any word or phrase that can be used to describe your character can be given a rating, so any word or phrase you use to describe your character can be the basis for a conflict. That’s how the game uses the same resolution mechanic to settle any kind of conflict. Before I get to extended contests let’s look at how the game manages scale. When the rating of a skill exceeds 20, the character gains a level of mastery in that skill. Instead of that skill’s rating going to 21, the rating goes to 1W (where “W” is the mastery rune symbol). Characters (and everything else) can have multiple levels of mastery as well. Two levels of mastery is noted like this, say: 10W2. Six levels of mastery looks like this: 15W6. When mastery is involved, the results of the player’s roll are bumped up one ranking per level of mastery, so that a fumble becomes a failure at one level of mastery, a success at two levels of master, and a critical success at three levels of mastery. However, when you and your opponent both have levels of mastery at play, the mastery cancels each other out one-for-one, so that two characters with opposing skills of four masteries each would roll as normal without any bumps, but if one character in the conflict has one level of mastery and another has three levels of mastery, then the first character rolls normally, and the second character receives two bumps to her roll. This way, a starting character has no chance against a god, which might have 6-10 levels of mastery, but as the character improves to become god-like in their heroic capabilities, their traits can rival even the mightiest beings in a fair fight. It’s a very clever way to scale powers without making one player roll 6d20 and have to add up all the results. Everything is simple and quick to calculate while still allowing for a robust resolution system. And it does it all without having to have a page of charts that are consulted and compared as in DC Heroes. So now lets look at extended conflicts. When the narrator wants to slow down a moment of conflict to make it a big deal, she calls for an extended conflict. In an extended conflict, the characters convert the rating of the skill used into AP, or action points. (DC Heroes also has APs, but they stand for “attribute points.) Each level of mastery adds 20 AP to your total, and followers and other factors can also affect your AP total. A character’s AP signifies their resources, determination, and positioning within the battle. In each round of the conflict, you bid so many APs (representing how much effort you are putting into that action, and how much you stand to gain or lose as a result), and the dice determine how you and your opponent’s APs are affected in that exchange. You might gain APs, steal APs from your opponent, lose APs, or give APs to your opponent. To determine what happens, you compare your dice results on a chart similar to the one used in simple contests (which I have also included a copy of below). I’m a big fan of mechanics that map out the beats of a conflict, like Dogs in the Vineyard’s where each action and counteraction is created narratively by the playing of the dice in your pool. Hero Wars’s extended conflict recreates this effect, and I find that exciting. I like that your bid of APs shows how much you are risking, how big an attack you are making, so you can engage at any level from making a test of your opponent’s strength to a desperate all-or-nothing attack. The weakness of this system is that the game provides not natural way to limit the numbers of exchanges in an extended conflict. If players are cautious and the dice are wonky, AP totals can go up and down indefinitely. Dogs in the Vineyard has a maximum number of exchanges by stint of your limited dice pool. Trollbabe, which has a similar mechanic_ forces every encounter to max out at three exchanges. Nothing in Hero Wars puts a cap on the extended conflict. Laws was of course aware of this weakness and advised in the Narrator Book for the narrator to solve the problem by making the narrator’s character act foolishly: “If an extended contest seems to be dragging on forever, with cautious contestants passing small stakes back and forth throughout a long succession of exchanges, throw caution to the wind and have your narrator character stake all his remaining APs on a final, climactic exchange” (7). That’s certainly a way to do it (and the way I would do it) but that seems clumsy at best. This rather elegant system deserves a much more elegant solution than that. Overall, I like the core mechanic of Hero Wars. It’s an impressive, flexible tool that allows for any kind of conflict at any scale. Through the course of reading the various books or just playing the game, it seems like the narrator can quickly pick up appropriate ratings for various challenges of all sorts. Except for the unsteady and unreliable end-point of extended conflicts, I’m a fan.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed