|

Alas for the Awful Sea marks Hayley Gordon’s and Vee Hendro’s entrance into indie TTRPG publishing. The game was Kickstarted in 2016 and saw print in 2017. While it does not use the powered by the apocalypse branding, it does use “The Apocalypse World Engine,” as credited on the copyright page. In fact, the game hews pretty closely to Apocalypse World in moves and play, not especially surprising for a freshman effort by designers. The real and lasting draw to Alas for the Awful Sea, for me at least, is the setting. Players take on characters who crew a ship through the British Isles sometime in the mid-19th century. The weather is cruel, the sea is dangerous, and the people and times are equally hard. In preparation for the game, the GM creates a town with two or more groups in conflict with a number of “currents”—“connected and interwoven problems and situations, exploring one centra conflict.” The GM is encouraged to tie the PCs into the town by creating connections, and then the PCs interact with those conflicts and currents as they see fit. In classic Apocalypse World fashion, GMs are encouraged have a set of backstories and concerns, but no plot, playing to find out what the PCs make of the difficult situations presented them. Over the course of the game, PCs visit various towns as the world of that group is slowly fleshed out. The advancement system is designed to anchor the characters to the developing world, to call on previously gained knowledge and previously encountered NPCs. The setting is thoughtfully reduced to six bullet points to guide the GM:

Each one of those points is expanded upon following a short introductory chapter. It’s a powerful description of the world, and as I said earlier, one of the most compelling parts of the book. Between that section and the later chapters on folklore and the history of the times, Gordon and Hendro do an admirable job bringing the world to life quickly and easily. You do not need to be a historian to understand the troubles and challenges of this world. You are encouraged to take this historical setting and fictionalize it, a job made easier, by the encouragement to bring regional folklore into your game, not as colorful background, but as present reality. For the most part, the presence of selkies and ghosts is the job of the GM, but the mechanics do make it all tangible for the players through the game’s version of Apocalypse World’s psychic maelstrom: the beyond. PCs can use the move “sense the beyond” to apprehend the other worldly mysteries GM’s are prompted to include in their scenario. It would be nice to see the folkloric aspects integrated more fully with the rules and procedures of the game, but there’s nothing lost by setting all that on the GM’s shoulders. The chapter on folklore is just a collection of creatures, spirits, and places that you can bring into your games. As has been popular in a few other games inspired by Apocalypse World, the PC character sheet has two halves to it. Each player picks a position on the ship (captain, boatswain, sea dog, stowaway, etc.) as well as a “descriptor,” a narrative background or impulse that defines the character (the lover, the kinsman, the believer, the creature, etc.). These two selections give you your special moves and a set of prompts for creating the relevant details for engaged play. The moves are competently made, but there is nothing in here to surprise or advance the art. Where I think the game does do something innovative and interesting with regard to the PCs is the advancement table. An advancement is given for each PC at the end of each “tale.” At that point, they get a pre-determined advancement (such as an improved basic move, a familiarity, or new bonds with other characters), and one of their choice, including the option to create a new move for that character. The list shows that the designers had a clear understanding of what they wanted to accomplish through advancement and how they wanted play to develop over time. Each option makes the previous tale mean something going forward. Your character learned something knew, met someone important, improved in a skill, or changed significantly in some way. As a result, future tales will involve reaching back to the experiences that have come before in order to be more effective going forward. Importantly, improving stats is not an option in advancement. This is not a game where the characters will become smarter or stronger. It’s one in which they will learn and grow. The other aspect that I think is will done is the half-page GM sheet, and specifically, the list for “Making Things Worse.” Instead of telling players to “be prepared for the worst” as the Bakers do in Apocalypse World, Gordon and Hendro tell players that “The GM makes things worse,” a phrasing that I did not think improved upon the original. However, they broke down GM moves for making things worse in an interesting and productive way, noting that the GM can “complicate the moment,” “change relationships,” or “complicate the future”: Complicate the moment That’s a clean and useful guide for thinking about ways to, indeed, make things worse. It shows a clarity and vision that we see develop and grow further in the games that Gordon and Hendro go on to make after Alas. The book comes with a pre-made tale in the final section of the book. This tale, which shares its title with the title of the game itself, makes it clear that Gordon and Hendro have a talent for creating scenarios, but it also shows that the GM tools provided with the game are limited and will need creative expansion by the GM to be fully playable. As I mentioned earlier, GM prep involves creating a town and a number of “currents.” There are sheets to aid the GM in creating them, as well as a list of appropriate conflicts to sit at the heart of all these troubles. Interestingly, we are never given the town or currents sheets for the included tale. Instead, we are presented the tale much as you would find in a purchased module for any number of other games. We are presented narratively what the PCs will encounter and how NPCs will react to them. We can deduce the various conflicts, but they are never named. We can piece together what the currents might be, but they are never laid out for us. That’s because, I’d argue, the town and current sheets are merely organizational tools, and incomplete ones at that. The reason I call them incomplete is that the final tale of the game does much more than you are ever prompted to in the worksheets. Namely, you have to create a relationship map. The reason Alas for the Awful Sea works so well as a tale is because all the characters and relationships cross the various conflicts and concerns. Relationship maps were first introduced in Ron Edwards’s Sorcerer supplement Sorcerer & Soul. In it, he proposed that open-ended scenarios could be created by structuring not a plot, but a background story full of characters needs, wants, and baggage. That is precisely what Gordon and Hendro put together here. I anticipated running the scenario for a friend I’ll be introducing to roleplaying soon, and to get a better grip on the tale, I turned it into a relationship map, and everything ties beautifully together. Ideally, the GM tools of the game would give you guidance if not tools for tying the various threads together via a web of relationships. What we are given is certainly workable, but it reminds me of that joke about the old instruction for drawing an owl, in which you first draw a circle and an oval; then a couple of lines for the shapes of the wings, legs, and eyes; and then in the final step you are told to draw in all the details that make this collection of lines into an owl, the caption of which in the joke is, “draw the fucking owl.” It is probably too much to ask first-time designers to create such tools, but without an innate understanding of them, GMs will most like just draw their adventures from the published tales or work through trial and error to see what works. I haven’t got to play the game yet, but I’m hoping to soon. I’ll start with the included tale, and if it goes well, I’ll venture into creating a town and currents for myself and see what it takes to go well. While there is nothing to amaze in this short volume, there are a few treasures that make it worth the reading, assuming you are already interested in its basic offering.

0 Comments

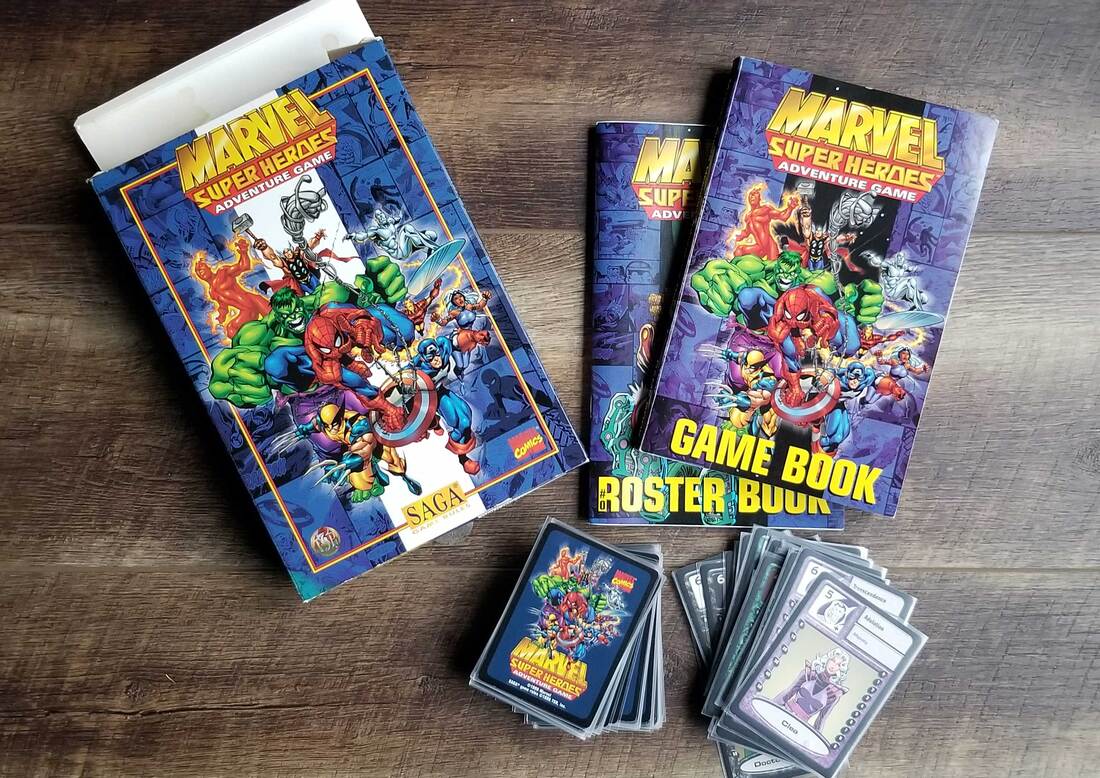

Here’s how the SAGA rules work in the Marvel Super Heroes Adventure Game, first published by TSR in 1998. The system was first used in TSR’s 1996 DragonLance Fifth Age, but Mike Selinker made some significant changes to the system from the second game. I’ll be pointing out differences as I go. If you’re interested in a thorough explanation of the system as it appears in the DragonLance game, check out my related post. The heart of the system is still the Fate Deck. The deck has 4 main suits, each corresponding with a character statistic. The green suit aligns with Strength, the red suit aligns in Agility, the blue suit aligns with Intelligence, and the purple suit aligns with Willpower. Each of those 4 suits has 20 cards, with their values spread out in a bell curve. In each of these main suits, there is one 1; one 2; two 3s; four each of 4, 5, and 6; two 7s, one 8, and one 9. The average draw, then, will be a 5, and over half the draws will be a value of 4, 5, or 6. This curve removes some of the swinginess of the DragonLance’s Fate Deck, which has 8 main suits of 9 cards each, valued 1 through 9. Moreover, the deck (and game) is simplified by cutting the number of stats (and therefore suits) in half. Now, instead of having one suit for acting and a different but related suit for reacting, you just have the one suit no matter how you are using that stat. Whether you’re using your agility to move swiftly through a crowd or dodge an exploding arrow, you just need the one stat. And just has the DragonLance Fate Deck has a ninth suit, the Marvel Fate Deck has a fifth suit, the Doom suit. This last suit has only 16 cards: one 1, one 2, two each of 3 through 8, one 9, and one 10. The average draw will still be a 5, but the Doom suit has more built-in swing to it, and it allows of course for the only 10 in the deck. During play, each player of a Marvel hero has a hand of cards drawn from the Fate Deck. The hand size will be between 2 and 6 cards, depending on the character’s “edge.” Edge is the game’s way of measuring experience and resourcefulness of a character. Captain America and Dr. Doom both have the highest edge available, whereas new and inexperienced heroes will have lower edges and fewer cards in their hand to choose from. When your character goes to perform an action which might fail and might lead to trouble, the GM will determine what stat is being drawn upon to complete the action. A character’s stats range from 0 (inordinately weak) to 30 (cosmically strong). 3-4 is the average human’s stat, with 7-8 being professional levels of natural and learned abilities, 10 being the maximum unaltered human potential, and 12 indicating the maximum enhanced human potential. As you can tell from that, the number indicate an exponential curve rather than a flat one. Once the stat is determined, the GM decides the level of difficulty for the action. Difficulty levels also curve exponentially, represented by numbers in increments of 4, maxing out at 40. An easy task is rated at 4. An average task is 8. A daunting task is 16. A superhuman task is 24. A godlike task is 36. An impossible task is 40. With the stat and the difficulty determined, the player can then play a single card from their hand and add the value of the card played to the score of their appropriate ability. If that total matches or exceeds the difficulty number, then the character achieves success. If that total fall short of the difficulty number, then the character fails to meet their objective. So, if Captain America, with a strength of 10, uses his strength to, say, lift something or punch someone into next week, the player can add one card to it with a value of 10 maximum, bringing the total to 20. So how does Captain America achieve a task that is “superhuman”? There are two ways to increase your total for incredible achievements. The first is the use of trump cards. A trump card is any card whose suit matches the suit of the action. So if Captain America is using his strength, and the player plays a Strength card, that is considered trump. When trump is played, then the player gets the value not only of the trump card played, but additionally, they get to flip over the top card of the Fate Deck and add the value of that extra card to their total. Better yet, if that flipped card is also trump, then they get to do it again, and to continue to do it until a non-trump card is flipped. This allows for critical successes. The other way to play extra cards is tied to the character’s edge score. Edge scores range between 0 and 4. I said before that Captain America has the maximum edge score, so he has an edge of 4. Players can play cards whose values are equal to or less than the character’s edge score for free before playing their one main card. So if Captain America has two 3s, a 5 and an 8, then the player can play both 3s before playing the 8, giving Captain America 14 to add to his strength score of 10. And if that 8 is trump, then on average he’ll flip over a 5 taking his total to 29 (or whatever the actual value of the card is). From that, you can see how edge measures a characters resourcefulness and experience. It not only gives them more cards to choose from—which means they have a greater chance of having cards in trump for any given action—but it lets them make better and more use of their smaller cards. A character with an edge of 1, only has a hand of 3 cards and can only play 1s for free when performing an action. Every action in the game is tied to this same system. Powers are given “intensity” ratings, which are exactly like ability scores, and each power is given a suit so trump remains consistent for them. When an action is opposed, things get even tougher. It is an easy task (so, a 4) for Cyclops to shoot his optic blast at a villain, but the villain gets to add their score to the target number if their doing any thing other than taking the blast. So if Sabertooth is dodging Scott’s blast, then the GM add’s Sabertooth’s Agility score of 10 to that easy’s 4, bringing the total up to 14. In fact, it’s harder than that. The Fate Deck isn’t just for players to draw from. The design of the game hooks the Fate Deck into most mechanically significant exchanges. I’ll explain how in just a moment, but first let’s touch a little upon the SAGA system design philosophy. When William Connors designed the system for DragonLance, the idea was to center the mechanics on the heroes of the story. As such, all actions were structured from the PC’s perspective. To this end, the GM never drew a card when an NPC attacked one of the PCs. Instead, the NPC’s success or failure was determined by the PC’s reaction. That same philosophy is carried over into Mike Selinker’s iteration of the ruleset. When Sabertooth claws at Captain America, the success of that attack is determined not by the actions of the NPC or the GM, but by the reaction of Captain America. Captain America would make an easy resistance using his agility to dodge the attack, but Sabertooth’s strength of 10 would of course be added to that difficulty. If Captain America’s player has the cards to successfully dodge Sabertooth’s attack, then Sabertooth misses altogether. If Captain America’s player doesn’t have the cards, then those claws hit their mark. We can talk about damage soon enough, but let’s first look at all the other ways the Fate Deck is used in play, especially by the GM. First, each card has an “aura,” either a positive, negative, or neutral value. This variation is spread evenly throughout the 96 cards, so there is a 1 in 3 chance of drawing any particular aura. The GM can use this to answer questions that they want to declaim responsibility for but for which there still needs to be an answer. What’s the weather like? Do I happen to hear what they said? Does the bridge hold up under all this weight? The GM can flip a card and see if things are favorable, unfavorable, or neutral for our heroes. Second, when players play cards from the Doom suit, the GM pulls those cards out of the discard pile and places those cards in front of them. At any time, the GM can use those Doom cards to increase any one difficulty score by that much, giving the GM a pacing mechanism for building up to important and difficult climactic moments. When a player makes use of that 10 of Doom card, the players all know that it can come back to bite them in the ass later. Third, and finally, the GM makes use of the Fate Deck during combat scenes. The combat scene is the heart of any given game of Marvel Super Heroes Adventure Game. Having read several published adventures, I can tell you that they are set up with scenes of combat at all the turning points. At the start of each round of combat, called an “exchange,” the GM flips over the top card of the Fate Deck and lays it face up on the table. First the GM reads the aura. If it’s positive, the heroes get a second wind and heal up before blows are exchanged. If it’s negative, then the villains get a second wind and heal up instead. A neutral aura has no effect. Next, the GM is invited to create an “event” inspired by the card. Each of the 96 cards has the unique picture and name of one of the characters from the Marvel Universe, and each card has a unique phrase, appropriately called an “event.” Some example event phrases are “Personal Tragedy,” “Rescue, “Out of Control,” “Rookie Mistake,” “Explosion.” The GM can use this event phrase to introduce a new element to the exchange, complicating or changing the focus of the battle. Or alternatively, the GM can introduce the character pictured on the card into the scene, bringing in a new villain or another hero. It’s a neat way to keep battles from become stale exchanges of powerful strikes until someone passes out. And better yet, each event phrase is tied to a particular “calling,” which is part of each character sheet. Every character has a central calling, a reason they suit up and go out to fight the bad guys. Captain America is an “idealist,” The Human Torch is a “gloryhound,” Spiderman has “responsibility of power,” and Mr. Fantastic is an “explorer,” just to name a few. When an event matches a hero’s calling, then the hero must address that event, because it speaks to their very purpose for being here. Anchoring events to callings is a clever reminder to the GM to hook these things directly into the interests of the character, and therefore, presumably, into the interests of the player who chose to play that character. This summary of the mechanics has already taken up way more space than I would have liked, but let’s finish it out and talk about harm. Heroes do not have hit points or any such equivalence in this game. In fact, except for abilities, edges, handsizes, and intensities, everything on the character sheet takes the form of words, not numbers. So when a hero gets haymakered by a villain, you don’t have to write anything down. Instead, after you calculate the damage of a blow taken, you discard cards equivalent to or greater than that damage. So if Captain America fails to dodge that swipe by Sabretooth and ends up taking 8 points of damage, the player needs to discard cards from their hand that total up to 8. Normally new cards are drawn from the Fate Deck immediately after the old ones are played. Injuries however change that. If they have an 8, they can throw that one card, and their handsize is reduced by that one card until the fight is over. Or they can throw a 3, a 4, and a 1, and reduce their handsize by three cards until the fight is over. Or, lets say, the player has two 5s, three 6s and a 7, then the player is forced to discard two cards to meet the 8 minimum. In this way, the player’s handsize gets whittled away through combat, depleting their resources and options until they have to discard their last hand and pass out from exertion or their wounds. Again, you can see how starting with a handsize of 3 (which means an edge of 1) limits a characters ability to hang in through a battle. Whew! We got through the summary, hopefully in such a way that you can imagine play. There’s a lot here that I like. If you read my review of DragonLance Fifth Age, you’ll get my general thoughts on the design and focus of the system. Instead, I want to talk here about a couple features of the design that I didn’t get to touch on before. How does having a hand of cards affect play? That’s an important question and one that has occupied a good bit of my thinking lately. Please note that what follows are mere speculation since I have not been able to convince anybody to play a session or more of the game. There are several things that I think would be cool about having a hand of cards to look at while we play. The first and most obvious is that I can look at my hand and see exactly how my hero is feeling at this moment. If I have a fist full of strength cards, I know what kinds of actions I’m going to be successful at. If I have a fist full of low cards, I know that I’m going to start out relatively weak and hope to draw into better cards. If I have a number of high cards, I’ll know that I can start trouble and write checks that won’t bounce, as it were. In fact, the cards allow me to engage in a little play strategy. I might take on low-risk stunts to use the low-value cards from my hand safely in an effort to get bigger and better cards of the right suits before trouble comes looking for me. And I really love the notion of watching your hand size shrink before your eyes as the battle progresses. You can visually trace your limitations, needing to martial and deploy your resources carefully as the battle draws to a close. On the other hand, I can see some negative impacts during play. When I’m roleplaying using dice, I might play around with the dice, but I’m not necessarily focused on doing something to roll them. When it comes time to roll the dice, I’ll gladly do so, but I’m happy to take my time getting there. I imagine the pressure and desire to use the cards in your hand is acutely stronger because you are looking at specific resources just begging to be used and exchanged for different one. This naturally encourages us to move through the roleplaying as quickly as possible to get to the fight. There’s nothing innately wrong with that, of course, and in fact, this game is wisely set up to have all the mechanics geared toward that same thing. All aspects of roleplaying, of character interaction and expression, are left entirely up to the players and their imaginations. In other words, they are given no mechanical teeth. There are no mechanics for social interactions or any activity that doesn’t involve your abilities or powers. It occurs to me that it is no coincidence that this feature was used for a game in which you are expected to play with established characters in an established universe. We don’t need to learn who Wolverine is as a character. We don’t need to explore the depths of Storm’s character. We are already supposed to know them in order to play them. We can shout out catch phrases and do our best impressions of their swagger and quirks, and then lets get to them being awesome and punchy! The same thing can be said about the DragonLance game too, really. The characters there may be brand new and created by us, but we know the type of people they are: heroes. The gameplay is not designed to discover characters through play, but to express their heroism through play, which is best done through overcoming conflict than through a lot of talking and socializing. Those other elements might be expected, but they are flavor and at the discretion of the players, not enforced by mechanics of play. With all that in mind, it’s not really a negative, as my first sentence of this paragraph says, but a design decision to keep focus on the use of those cards. That pressure to play cards from your hand is part of the design itself, not an unfortunate byproduct, I think. I also give credit to the designers (of both games) for taking advantage of the affordances of their main mechanics. Skills in this Marvel game have an impact by lowering the difficulty score by a single rating (meaning 4 points). Hawkeye’s skill with archery makes shooting an enemy a zero difficulty rather than an easy difficulty (before adding in the villain’s opposing scores, of course). If you are one of the world leaders in a particular skill, then any card you play while using that skill is considered trump. That’s just elegant and clever design. Finally, I want to say how surprised I was to see how closely this game is related to the original Marvel Super Heroes roleplaying game designed by Jeff Grubb in the 80s. It became clear to me at some point in my reading the text that Mike Selinker sees his design as being a modernized take on Grubb’s game, drawing both on the spirit and the mechanics of the game. The tone nods to Grubb’s use of Spiderman and other Marvel characters as specific voices to explain the rules of the game. There is even an appendix for converting your FASERIP characters to this new system. If you don’t buy any of the Roster books, but have the old rosters from the earlier edition, then you have everything you need. Selinker is not bound by anything that has come before, but it is clear that he takes advantage of all the resources Grubb provided. The list of powers is hardly an exact match between games, but it is clear that the one is used as the foundation for the other. Skills are a clear offshoot of Talents from the 80s. In a lot of ways, Selinker saw his game as a second edition of the same game, not just a reinvention of the wheel. I found that endearing and cool. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed