Bacchanalia is a card-based story game designed by Paul Czege and Michele Gelli, and produced by Narrattiva. The game began as “Bacchanal,” which Czege designed for Game Chef one year, which used a bunch of colored and different-sized dice. Gelli then helped turn that into a card game. At least, that’s my understanding, so if I have that wrong, please let me know. The cards are beautiful in their own right with Claudia Cangini’s full-color art. In the game, players create a character who is a subject of the Roman empire and who currently stands accused (rightly or wrongly) of crimes against the empire. They are currently hiding in the town of Bertinoro from their accusers and the Roman soldiers who pursue them. Simultaneously, they are separated from their lover with whom they are trying to escape. The other thing you need to know is that it is a game of sex and violence, decadence of all sorts, as the gods Bacchus, Venus, Pluto, and Minerva are also present in Bertinoro to indulge in their own desires. Bacchanalia is a GMless/GMful game for 3-6 players, and each player is telling their own story, though the different tales can overlap and crisscross as they are all taking place in the same town. This is where I need to make clear that I have only read and studied the game, not played it, so take my observations and thoughts for what their worth. The mechanics of the game are cool and unique. Each player begins with a set of three cards on the table in front of them (these are called Deus cards). These cards determine which gods might have influence over your scene. Bacchus, Venus, Pluto, Minerva, your Accusator, the Miles soldiers, the Satyrs, Vinum (wine), and Amans (your lover) are all possible influences. This set of three cards changes--sometimes dipping below three, but seldom rising above three—through play. During your turn, you draw cards from the main deck, which is made up of cards that match the possible influences of the cards before the players. What you draw determines which of your cards is the “ruling Deus” for your turn. Having determined who the “ruling Deus” is, you consult a chart and see how your cards change, and what needs to happen in the scene you narrate for your character. The stories you tell are told in simple narration form. There is no freeform roleplaying during the scenes. Given the prompts and restrictions of your ruling Deus, you need to develop your character’s story, treating the other players as your audience. The game cleverly controls the themes and focus of your story by restricting you to ten types of scenes as determined by your ruling Deus. Those scenes will primarily bring you into a close encounter with those who pursue you (and the violence they intend), bring you together with your lover, or prompt you to describe scenes of sexual decadence. This is a game that will benefit greatly from players knowing each other or at least creating their play space so that everyone is comfortable and willing to make themselves vulnerable. Guarded play will likely end in “safe” stories or disingenuous acts of violence and sex. The game ends in any number of ways. You can escape with your lover to safety. You can save your lover but be destroyed by the forces that hunt you. You can simply fall prey to your pursuers without saving your lover. You can lose yourself to the wine-fueled revelries. Whether you are telling a love story or a tragedy can only be learned through play. That is always a feature that I love in a storytelling game. I really can’t say enough about the mechanics of the cards. There’s a lot happening with them, but never in a laborious or confusing way (once you wrap your head around what’s happening, of course). Certain ruling Dei make you discard a Deus and some make you pick one up (from the center of the table or from another player) so that the various Deus cards are shifting about the table. If you have Pluto, then it is likely that your accuser or the military will soon follow behind them. Venus will likely lead you to your lover. Bacchus and the Satyrs are interested in wine and debauchery. Only if you have the Amans Deus card can you hope to have the Amans the ruling Deus, which is the only way to escape your pursuers entirely with your lover. I imagine plays sends the Amans card floating around between players as they vie for the opportunity to save their character. The cards also provide a cool pacing mechanic. There is a single card in the deck of 62 that you draw from called the Parcae, or the fates. Whenever this card appears, you narrate a twist in your story and shuffle it and the discarded cards back into the main deck to refresh it. The Amans Deus card doesn’t enter play until the Parcae card has surfaced once, so there will always be a number of scenes before the lovers can even enter the story. Then, as the Parcae appears multiple times, the severity of the encounters with the military and your accusers increases so that once the Parcae has appeared 3 times, and the Miles is your ruling Deus, your character will meet their end at the hands of the military. It’s a simple pacing tool, but both effective and beautiful how it is left to chance to appear, just as its namesake would suggest. One of my favorite mechanics is that you can hold onto a drawn card for a turn if you want to. Doing so gives you a chance to influence who your ruling Deus will be the next turn (though of course it is no guarantee). So let’s say you have the Amans Deus card, and you want to save an Amans card that you drew this turn, hoping to make the Amans Deus card your ruling Deus next turn so you can escape with your lover. You “bow” the drawn Amans card (what would be called “tapping” is Magic: the Gathering did not copyright the term) to signify you are holding onto it. When you “bow” the card, you need to “incorporate[e] in[to] your narration a recognizable character or a peculiar location or object previously described by another player” (emphasis in original). In this way, the game forces your story to overlap with another player’s story by introducing some recognizable element from their story. This simple act will make the stories truly feel like they are happening in the same world at the same time. It’s the only time the game forces you to make such a connection (though of course you are free to do it in your narration any time). It’s a cool feature and a cool way to make “bowing” a significant act. This game was published in 2012, well before the recent spike in card-related RPGs, and it uses cards in a way I haven’t seen before or since. If you’re interested in card mechanics in RPGs, this is well worth checking out. You can still order physical copies here: http://nightskygames.com/welcome/game/Bacchanalia.

0 Comments

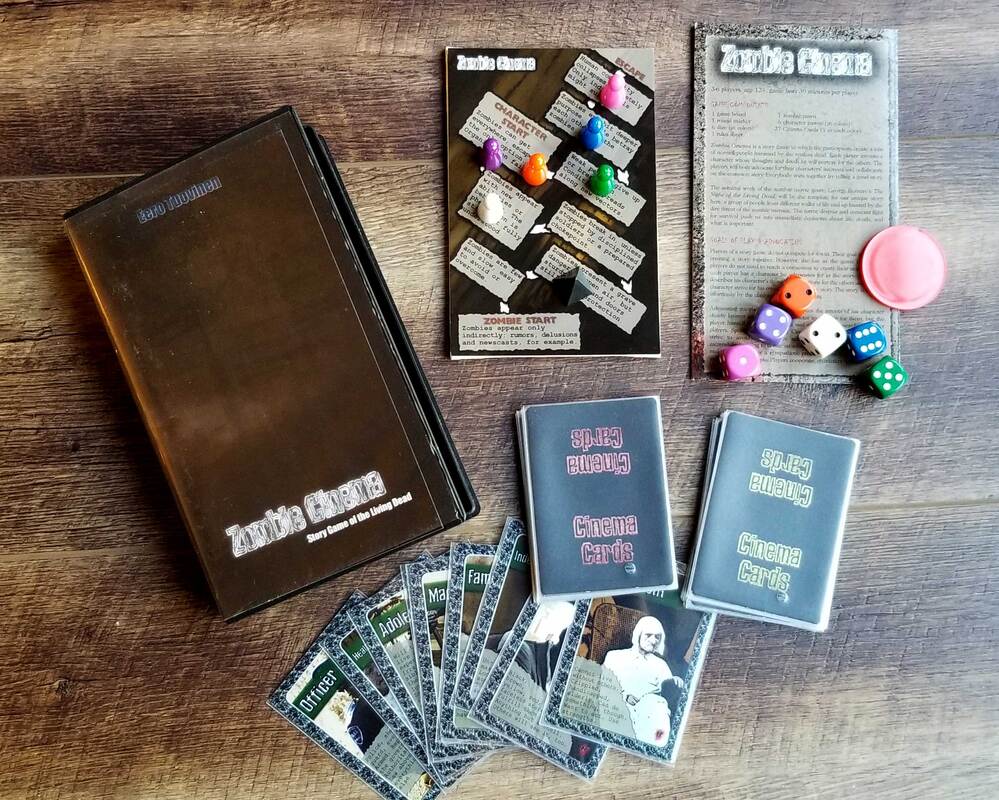

Eero Tuovinen’s Zombie Cinema was published in 2008, but I got my copy a few years ago from Indie Press Revolution, so it seems to still be in print. The game comes in a VHS case, and presents as a small board game that’s simultaneously a story game. The rules are short and direct, and the board is pasted onto a thin 5x7 canvas. The game is intended for 3-6 players and it plays out in a single session. The story you tell through play is that of a zombie survival horror film, Tuovinen taking his primary inspiration from George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. The game has some really neat mechanics, but it is a product of its day, which seems weird to say a mere decade later. Let’s start with the cool stuff. The board of the game has a single track. The zombie token begins at the earliest point of the track, and the player tokens begin 5 spaces ahead of the zombies and 4 spaces from the end. Each space describes the limits of the zombies’ power, so when the zombies are in the first space, we are told that “Zombies appear only indirectly: rumors, delusions, and newscasts, for example.” As the zombie token moves forward through play, the zombies appear first individually, slow, and limited, and as they progress, their numbers grow as do their determination, effect, and abilities. It’s a great way to pace the zombie pressure to match the typical zombie pic. The other cool thing the board allows you to do, and this is for me the golden tech of the game, is that scenes resolve by moving players forward, backwards, or nowhere at all. The game is GMless/GMful, and players take turns setting scenes and pushing for their own character’s survival. Each scene can potentially end in a conflict between characters. If it does, the characters who win the conflict get to move a step forward, and the losers have to take a step backwards. This means that your survival is dependent upon pushing others under the zombie bus. That’s cool and on brand. Conflict resolution is also neat. Each player has a uniquely-colored token and a matching uniquely-colored d6. At the time of conflict, the player initiating the conflict puts their dice forward. If the other player yields to the first player’s demands, they hold their dice and no conflict occurs. If the other player wishes to engage in the conflict, they too put their dice forward. Then the other players have a chance to affect the outcome of the conflict. Non-involved players can either pass, ally themselves, or support a side. If they pass, they hold onto their dice and stay out of the conflict. No matter how the conflict resolves, that player’s character is staying put. If they ally themselves, they add their dice to one side of the conflict. In doing so, they tie their fate (and token’s movement) to the side they ally themselves with. To support, the player places their die on top of the side they are supporting. This is a meta-action, in that the support is the player expressing their support for a side, not the character. The character doesn’t have to even be in the scene (or still alive) for the player to support one character. The supporting player’s character’s token is not affected by the outcome of the roll. Then both sides roll their pools and the player with the highest single die wins. The die mechanic is a good way to keep everyone involved and to let each player decide how they want to participate. The system also means that if you want to save your character, you need to seek out and participate in the conflicts in the scenes. It’s a smart way to make players happily create the drama the game wants to see. The zombies move ahead every round and can never be sent back, so there is an 8-round clock on the game. In addition, in any conflict in which the dice tie, the zombies take another step forward, so the odds say a game will average 6-7 rounds, with a minimum of 5. The zombies, combined with their naturally increasing threat levels, makes for an excellent timer. The main troubles from which the game suffers, in my opinion, is that it does nothing to share the heavy fictional lifting with the players. This is what I mean by the game being a product of its time. In the last 10 years, indie designers have learned all kinds of techniques to help create character relationships and material for scenes. Let’s start with character creation. The game has three sets of cards (9 in each set, 27 all together). To create characters, players draw one card from each set and will have a history, demeaner, and general appearance. Seems good. But the game does nothing to tie the characters together, so unless you have experienced players who know that the drama will benefit from ties and past relationship, expectations, and desires, you will end up with a game of strangers with nothing to talk about in any given scene except the zombies outside their door. Similarly, scene creation is left to each player during their turn with the simple prompt: “The active player makes the call on the time, location and participants of the scene like a shot in a movie.” That’s it. That’s all you’re given. There are no mechanics to help with the pacing of your story beyond the abilities of the zombies, nothing to create interpersonal drama. I can easily imagine a game in which every conflict results from character’s screaming at each other in life-and-death hysterics. It’s up to the players to create a thoughtful set of interactions, which is great is you are with experienced and thoughtful players at the top of their game. The character cards are problematic in their own way. One of the character roles is “Ethnic Minority”: “Black, brown, yellow, red, faceless stereotype. Fulfill them or not.” Yikes. I get that in white American cinema, the token character of color is a thing, but there is no reason for your game to continue that. Similarly, having that card suggests everyone else is white. Ugh. Another card is “Dependent”: “Cannot live without others. Cripples, handicapped, elderly. Can do something, though.” And of course one of your character’s defining traits can be “Mental Problems.” There’s a whole lot of cringing there. I haven’t ever played the game, and I don’t see myself ever playing it at this stage, especially with Zombie World out there. All the same, this game is designed to scratch a different itch than Zombie World does, and it has some innovative ways to get there. The problems with the game can be pretty easily solved with updated character cards, a relationship/history feature, and some basic scene-creation and conflict-creation support. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed