With the 3rd season of Stranger Things released, I pulled Kids on Bikes off my shelf to give it a read. This is the first game book in this genre that I have read--Tales from the Loop is so damn big (but beautiful, of course)! The art in Kids on Bikes has its own beauty (Heather Vaughn has a cool, moody aesthetic going on), and the book is strikingly lean, a mere 55 pages of rules and procedures. I was impressed with (and appreciative of) how concise the rules are; nothing is sacrificed in that concision. The game helps you tell stories of small-town mysteries of the Stranger Things variety, though there’s no reason the rules couldn’t be used for more mundane stories, like Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys stories. Actually, there’s no reason the rules couldn’t be used to tell any type of story in a small town because the rules of play don’t consist of anything more than a resolution mechanic. Characters consist of 6 stats, and each stat is given a die size—d4, d6, d8, d10, d12, d20. When your character attempts to do “something that runs the risk of failure” (27), you work out which stat your character is relying on to accomplish the thing, and then the GM assigns a target number for you to roll against. If you roll at or above the target number you succeed in your attempt. If you roll below the target number you fail in your attempt. The more you miss or exceed the target number, the worse your failure or greater your success. There is a chart to guide GMs in creating target numbers, and a chart to guide the players in interpreting the degrees of success and failure. That latter chart also dictates who has narrative control over the success and failure. That’s really the heart of the game once characters are created and the scenario is underway. There are no special mechanics for investigating a mystery, spying, meddling, questioning others, or anything else. I’m not a fan of creating target numbers as a GM, and simple success/failure mechanics leave me uninspired. The authors give advice to GMs not to let failures just mean the end of a line of inquiry, but there’s no mechanical way to make failure mean anything other than “you don’t get what you want.” That said, the game has a nice character creation system that builds your small town and places your characters into a web of relationships with the other PCs and the various NPCs that get created in the process. You choose strengths (which have mechanical weight) and weaknesses (which are purely fictional) and answer both relationship questions and personal questions in what looks like a fun session zero. The most innovative element in the game’s design is the creation of the “powered characters.” After the game begins, the GM can introduce a new character with powers (yep, just like Eleven). The powered character doesn’t belong to any specific player. Instead, the GM writes aspects or traits on index cards and distributes them to the players. Each player has control over those aspects on the cards they get. Through play the GM can reveal more about the character simply by handing out a new trait or aspect. So the players might only know that the character is shy, quick to anger, likes kittens, and hates confined spaces when they meet him. Those trait cards give the players what they need to play the character however they want within those bounds. Then as powers or other aspects are revealed, players gain control of those new aspects as well. The appendix in the book provides a list of aspects and powers to help the GM create powered characters without stress. The GM section devotes a good deal of time to safety and healthy, open conversation among the group. It also walks the GM through the process of mining the information revealed in town and character creation for hooks and story ideas. It’s a solid suggestion, and happens to follow my usual process—I thought it was well explained with the authors’ typical concision. What the game doesn’t give the GM is any tools for making story creation or running the game any easier. With a resolution system and some advice about story creation and working with players and controlling pacing, the game leaves the rest up to the players. In short, the game has a great setup, a workable resolution system, and some fine advice. That’s probably all any experienced gamer needs to have a good time, but it’s certainly not all I want a game to offer.

0 Comments

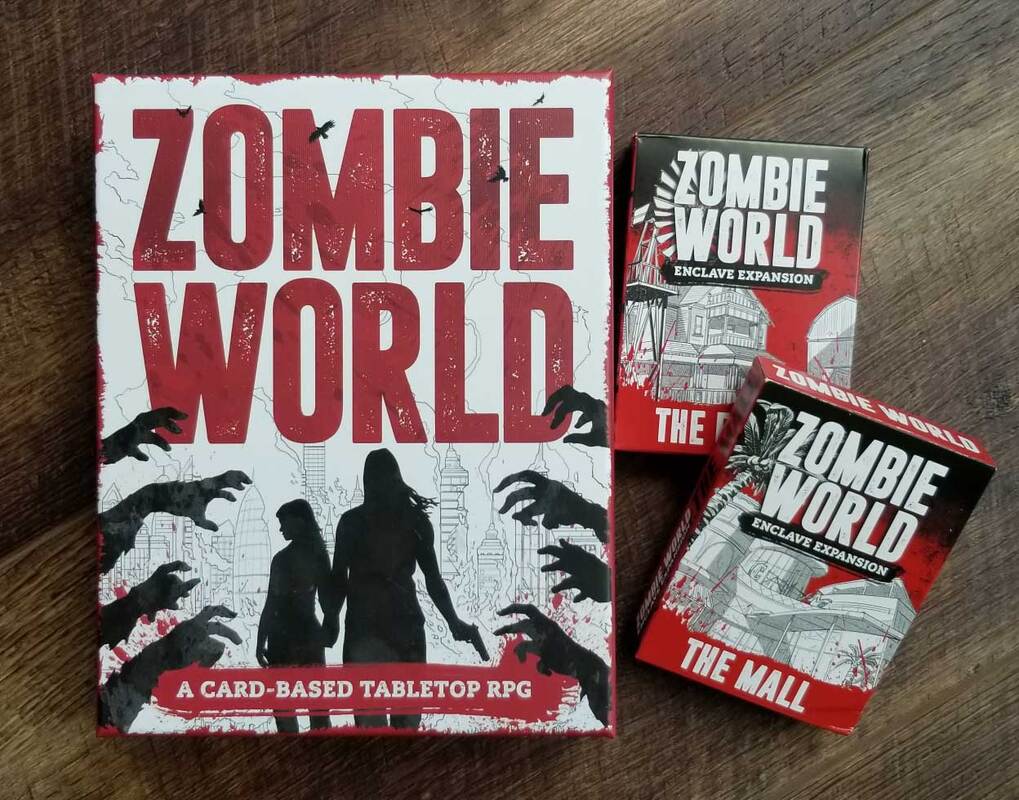

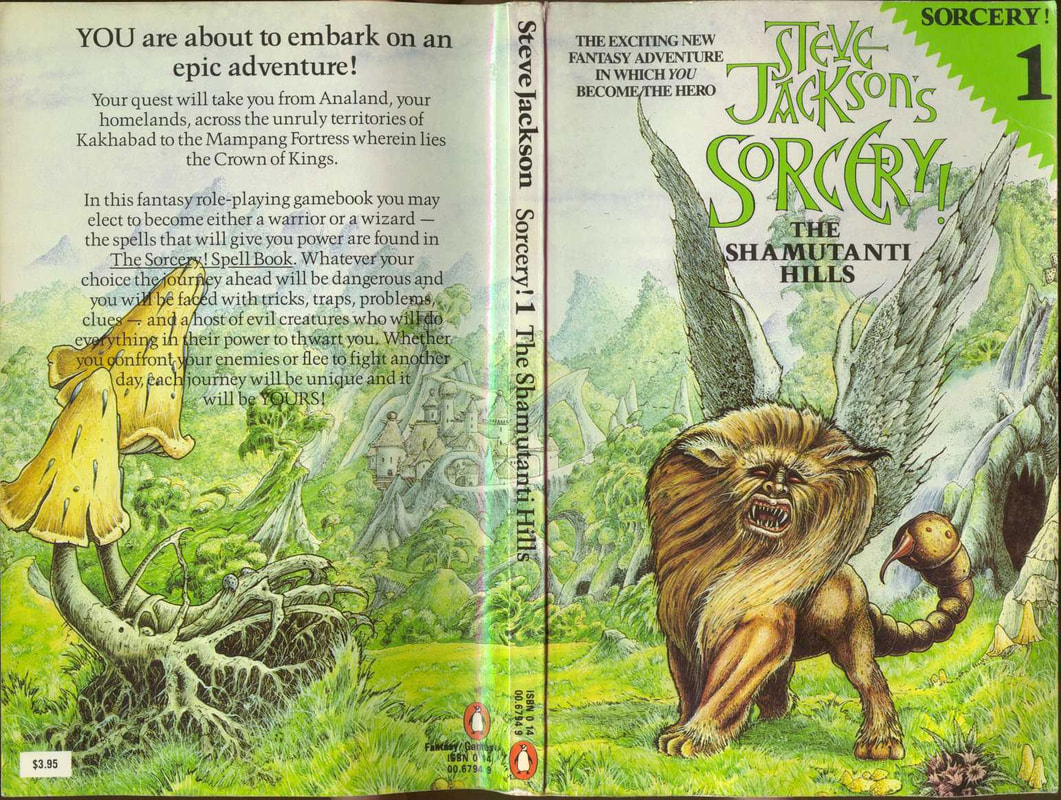

Magpie has finally sent out rewards for their Zombie World Kickstarter, and the game should be widely available at this point to the public. I say “finally” not because they were long overdue, but because I was excited to see the product. I had not read any of the draft and early rules that Magpie shared through the Kickstarter, so reading through the rules and cards were my first experience with the game. There is a lot to love here. There has been a lot of experimenting with packaging and presentation in the RPG field lately. We’re seeing a lot of games being published that don’t take the form of a single book. Star Crossed comes packaged with a set of tumbling blocks, printed cards and character sheets, and a pamphlet of rules. The King is Dead has individual play booklets and various optional sets of cards. The Companions’ Tale is a card game with a thin booklet of rules. While these innovations eat up a lot more room on our bookshelves, they all cut down drastically on the amount of time we have to invest in learning to play the games. And of course they emphasize the “game” part of the title role-playing game, making these games look like other games sold in small and medium boxes. Zombie World makes it so that you do not even have to print anything out. If you have the box and its contents with you, you can play the game without needing so much as a pencil. (Well, okay, you might want to have a set of dry-erase markers, but you can make do with the one provided if you’re a patient and friendly group.) The rulebook is a small and beautifully produced 5”x6.5” booklet of 33 pages. Unlike Star Crossed, Zombie World doesn’t avoid the RPG title or terminology, but it does avoid giving overelaborate instructions, assuming a base familiarity with RPGs or assuming that a base familiarity is unnecessary. The game comes with 8 glossy cardstock character sheets that can be written on with dry-erase markers. Because your character’s details come primarily on the playing cards that are the center of the game, there is very little information that players need to write on their sheets. There are 4 stats, a stress track, a space for you name, and an area to write the names of the various NPC allies you have. Other than that, the card includes two basic moves, and a place to put your character cards associated with your past (pre-zombie occupation, your present (job within the enclave of survivors), and your trauma (that you suffered surviving for as long as you have). Players also get a glossy card with all the other basic moves they’ll need for the game (yes, the game uses Apocalypse World mechanics, but it doesn’t market itself as a pbta game). The moves are divided into basic moves on one side of the card and zombie moves (meaning, moves you make when dealing with zombies) on the other side. Anything else you might need to play your individual characters are included on those set of cards I already mentioned with your past, present, and trauma. The GM gets their own glossy card, with the order of play and a few specific rules on one side of the card, and a set of lists on the other side. Those lists are things like useful items that will probably enter the fiction at some point, places characters might visit, and names for NPCs. The card also includes two of the moves the players will commonly make, for the GM’s convenience. The rest of the game exists in a series of decks of regular-sized cards. There is a deck of pasts, presents, and traumas. Your past begins in the face-down position, and the card gives you instructions on what you have to do within the fiction to reveal your card in play. Once it is in play, it gives you a bonus under certain thematically-relevant conditions. Your present begins play face up and can consist of a variety of things. You might change a stat because of your role, or you might have a special move that you have access to. All present cards give you a unique way to clear stress from your stress track. Like pasts, trauma cards begin face down. As long as they are face down, you can use that information to guide your roleplaying, but they don’t have any mechanical effect on play. You can reveal your trauma anytime you want once you’ve brought your character revealing the trauma into the fiction. When you reveal it, it might, like your present, affect your stats or give you a special move. Moreover, while it is revealed, you get a new way to clear stress (though that way is typically by engaging in that traumatic behavior) or some other tweak to how your character plays. There is also an enclave deck. At the beginning of play, you choose which enclave your survivors will be living in. Each enclave consists of two cards. The first card gives you a couple of moves that are unique for that location. The second card has a list of options for your enclave, lists of scarcities, populations living with the enclave, surrounding geographical features, and possible advantages. At the beginning of play, because characters are made, players take turns selecting items from the lists to define the specific advantages and drawbacks of their chosen setting. There is an advantages deck that has one card for each possible advantage listed on the various enclave cards. When they players choose an advantage, you pull that card out of the advantage deck, and it will let you know how that advantage affects the fiction and play, usually giving you a special move for when you try to make use of that advantage. There is a Fate deck. These card each have two uses. Each card has a quick relationship detail. After the enclave is created and characters are sketched out, the Fate cards are handed out between players to randomly assign a relationship fact between their two characters. The Fate cards are also used as a way to kick off a session by providing an immediate crisis that the enclave is facing. Whenever the situation is settled and a new status quo develops, the GM can draw from the Fate deck and see what new crisis tilts the enclave’s equilibrium. The last two decks are used the most frequently once the players enter fictional play. The Survivor deck is the main deck used in resolution. The deck consists of 11 cards. There are 6 misses, 3 edges, 1 triumph, and 1 opportunity. A triumph corresponds with a 10+ in regular pbta games. Edges are like the 7-9 result, and misses are misses. The opportunity is a miss, unless the player wants to mark a stress on their character; if they do, then the opportunity counts as a triumph. So whenever cards need to be drawn, the 11 cards are shuffled and the player draws a number of cards equal to their stat for whatever move they are making. You can then play any one of the cards you drew (typically the best card, of course). The Bite deck is the final deck. It has 15 cards in it, and it is drawn from whenever a PC has a close call with a zombie. The deck has 5 “safe” cards (you’re safe), four “something breaks” cards (which gives the GM permission to break something in the environment to worsen the characters’ situation), four “more zombies” cards (you get it), and one “bite” card. If you draw the bite card, your character is going to die, no ifs, ands, or buts about it. The GM and player can work out when and how that happens together, but it will happen before too long. The bitch of the bite deck is that it is not shuffled after each draw. It is shuffled once at the start of the session, and then it is not shuffled again until the bite card is drawn. Right? Situations for the game write themselves, so there is no prep needed by the GM. The enclave has weaknesses, the characters have drives, and there are hordes of zombies in the outside world—things can take care of themselves from there. In one-shots, the story is about these particular characters surviving (or not) in the zombie apocalypse. In campaign play, the story is about the enclave and how it stands or falls no matter how many individuals pass through its halls. There are a lot of things I love about the way the game is constructed. I love that past and trauma cards remain face down until you want to introduce them. So you can reveal or hide them for a number of reasons. First, you can use them to fuel your roleplay, hinting at things if you want or not if you don’t. Second, you can reveal them at a dramatic moment, if you choose. Third, you can reveal them solely because you want the benefit they offer. Finally, you can choose not to reveal them and not to let them inform your roleplaying. You don’t get to choose your past or trauma; they are just given to you. So if you get a trauma you don’t want to play out, don’t. If you never flip the card over, it never enters the fiction as a fact, and you can have whatever past and trauma you imagine for your character. And when you don’t flip the card, there is implicit tension there as other players wonder what they don’t know about your character. In addition to all these cool things, the help or interfere move makes you draw cards equal to the number of face up cards the player you are helping or interfering with has. It’s a quick and easy way to see how well the enclave knows your character, how vulnerable and exposed they have been made in this apocalypse. And since you can gain multiple traumas through play, you can conceivably have someone draw 5 cards to help you, which is one hell of an incentive to be open. Traumas are also a neat way to have your character exist thematically in this apocalyptic world. Every time something goes wrong, you have to mark stress, because this is a stressful world. When you mark your fifth stress, you erase all your stress and take a new trauma. If you ever draw a fifth trauma card, your PC becomes and NPC. But each trauma can also make your character stronger or more effective in some way, so gaining stress and trauma is not a frustrating experience for players. As such, the game rewards you for leaning into the thematic content of the game. In addition, the more trauma you have, the more tools you have to clear stress, so there is a self-correcting tool to let you slow down the traumas you’ll have as you go. To make matters better, the means for clearing that stress makes for excellent drama. For example, one trauma is “xenophobic.” To clear stress once you are xenophobic, all you have to do is “barricade a place and someone is left outside.” Oh shit. That’s awesomely horrible. In addition to trauma of course, you can be taken out by other means. PCs do not have hit points or a harm track. So the only ways to be removed from the game outside of trauma is if you draw that bite card or if you draw a miss when you suffer serious harm. Suffer serious harm is a harm move for non-zombie violence, and it’s a really well-designed move. If the harm you suffer isn’t serious, just play it as an inconvenient and quick-healing wound. If it is serious, then you draw cards from the Survivor deck. The number of cards you draw is determined by how intentional the injury was (was someone trying to kill you?), how lethal the source of harm was (were you shot with a gun?), and whether you had any protection (were you wearing a flak jacket, by chance?). In the worst case, you draw just one card, which gives you more than a 50% chance to miss, and on a miss you die. Those are serious stakes. Death in this game is necessarily always on the table. The basic moves are wonderfully conceived as well. Your move to influence someone else demands that you “get in someone’s face.” There is no seduction or manipulation, only savage aggression. But my favorite basic move is the do something under fire move: “When you try to avert disaster, say what you’re trying to prevent and draw Survival. On a Triumph, you manage it. On an Edge, you pull through, but it will cost you. The GM will offer you a hard bargain, ugly choice, or Pyrrhic victory.” To me, the beauty of this move exists in the wording of the trigger: avert disaster. You know exactly when to make this move and when not to. Are you trying to do something hard? Who cares! Is that hard thing a desperate attempt to avert disaster? If you fail, will disaster befall you and your friends? It’s such a clear fictional marker and it avoids the abuse or over use of the move to cover situations for which it is not intended. I love it. I haven’t had a chance to play the game yet, but I’m very much looking forward to our next one-shot night! Recently I reread Robin D. Laws’s essay “The Hidden Art: Slouching towards a Critical Framework for RPGs,” published in Inter*Action in 1994. In it, Laws proposes ways to approach critical analysis of RPGs by looking at how film was analyzed and criticized from the time it was a young art form to when it became a readily acknowledged artform of its own. I first read the article three years ago when I was beginning my journey into RPG theoretical thought. I hadn’t yet read much of Ron Edwards’s essays from the Forge or Vincent Baker’s “anyway” blog posts, and I was excited about what this field that was new to me would yield. At that time, I was impressed by Laws’s writing and voice, but I didn’t get much from the essay, primarily because it didn’t discuss analysis of the sort I was interested in. Approaching it now, however, I was struck by how insightful he is, and how he misses the central question at the heart of what he discusses. Laws gets a lot right in this essay, and is at times prescient about where we have come. His proposed political analysis of D&D is one I see people discussing (and arguing over) still today (notably without any credit to Laws): An enterprising critic could have a field day with the way [D&D] experience point system primarily rewards killing enemies and stealing their gold. It’s hierarchical character development system, with characters going up ‘levels’ and thereby becoming more effective at killing enemies and stealing their gold, would be further grist for the academic Marxist’s mill . . . [A] politicized critic might argue that the game is significant not for any aesthetic reasons, but because its success in the marketplace makes it a barometer of social and political attitudes, even those held on a subconscious level. (95) Laws looks at auteur theory in film and wonders if such a thing could apply to RPG design. Laws’s interest in auteur theory is connected to genre in film, but one could argue that there is most certainly something of an auteur belief system that grew up in the indie scene as certain game designers have unique approaches and elevated status. Laws wonders, Beyond this lies the question of whether we wish to study the works of particular game authors for common threads, and single out certain of them for a pantheon of achievement based on our discoveries. (94) This kind of analysis is certainly happening now and has been going on for some years now. But as much as I enjoy looking at Laws’s successes, I’m more interested at the moment in his failure in this essay. In comparing RPG studies to film studies, Laws observes that to discuss RPGs we need to figure out what it’s language and grammar is, just as film critics needed to discover the unique language and grammar of film: It took years for a visually oriented approach to film to develop, one that attempted to discover a new vocabulary to describe the visual grammar of film. The artistic decision behind the making of a film was not confined to the writing of its dialogue, but also included editing, set design, shot composition, camera movement, and many other elements that had previously been considered only subliminally. (92) What Laws lands upon as a possible grammar of RPGs are the mechanics of the games: One fruitful avenue of exploration would be the issue of game mechanics, and how they hamper or hinder the narrative building process. Does a critical hit table or skill resolution roll fulfill the same sort of purpose as a camera angle? A hard cut between scenes? A fade-out? (93) That’s of course a clever approach, and a reasonable one. But it misses what is the core element of RPGs, the very medium of RPGs. Films unique medium is a two-dimensional moving visual frame. In RPGs, that medium is not mechanics, but conversation. RPGs exist only in the exchanging of words and thoughts between the members in the group. Mechanics are engaged through the conversation and become the subject of conversation and in turn shape the conversation and how a game plays out at a table. Obviously, the observation that conversation is the medium of RPGs is not my own insight. I first learned it from Baker’s “anyway” blog, and the topic was central to conversation happening on the Forge. I do not know to what extent that thought is just an accepted fact, to what extent it is disputed, and to what extent it is unknown. I think it’s funny when I hear people talk about pbta games as though they are unique in having something central called “The Conversation,” as though the conversation is a construct created by Apocalypse World and its successors. So what struck me in my reading of Laws’s essay this time through is that we now have the answer to the question, what is the medium of RPGs? And the answer to that question allows us to launch again from where Laws brought us in his essay and think about what is the “grammar” of that conversation, as created by various RPGs. Comparing Eisenstein’s editing to Orwell’s mise en scene has parallels in the conversation that happens at an RPG game. How is the conversation divided? Who introduces new information into the fiction, and how, and when? Who can introduce backstory, and how, and when? How often does one player talk, and for how long, and what is the nature of their statements or questions? All the rules and procedures of the games shape and affect the conversation in the same way that camera placement, lens selection, film choice, and editing affect the visual created for a film. That analogy moves from being a merely interesting idea to a productive line of thought, or at least it does in my head. Perhaps I am having revelations and thoughts that are commonplace and old hat. That happens. The lesson for me in this is not to think of any piece of writing as having been “read.” You will always be in a different place in your own head and experience each time you read a thing, so revisit and reread and rediscover.  I never read the Fighting Fantasy books when I was young, didn’t even know they existed. I first learned about them in the last three years as I’ve been digging into RPGs and narrative games. For plenty of game designers, these solo adventure books were early inspiration, and having finally read one of them, I can understand why. I decided to start with the Sorcery! Series because I didn’t intend on reading a lot of these books and I remember reading about this particular series on Vincent Baker’s “anyway” blog when someone in the community brought it up in a discussion about magic systems. When someone brought it up again the other day, I decided it was a sign to dive in. The trick of this specific set of five books is that you play a sorcerer (surprise!) with a spellbook of 48 spells, only it is unsafe to bring the spellbook on your journey, so you have to have your spells memorized when you play. Each spell has a three-letter name, which is related to the nature of the spell, some closely related, other more obscurely. The fireball spell, for example, is HOT, and the lightning bolt spell is ZAP. DOZ lets you slow down an attacking creature to one-sixth its regular speed. Of course, you might forget and think it’s a sleep spell. Some spells don’t require anything other than your stamina (one of your character’s stats in the game), while others require a general or specific ingredient. One spell, for example, requires sand, while another needs a Bracelet of Bone. The Sorcery Spell Book lists all 48 spells roughly in order of relevance, each with a picture; the name of the spell; a description of the spell, its limitations, and any ingredients required; and the cost to your stamina to cast it. It’s a simple, but nicely designed book. While it sucks that you have to shell out the extra money for it if you want to play a wizard in the regular game books, it’s a neat little artifact and makes it easy to not cheat, if you want to follow the rules of the book. When you come to an entry in the game books in which you are asked if you want to cast a spell, the book gives you five of the three-letter titles, but not all of the options are real spells. So you need to know, which spell you want to cast, what it’s called, if you have enough stamina to cast it, and if you have any ingredients necessary for the casting. When you make a wrong choice, you have to spend the stamina anyway, so it can be costly to make a mistake. If you choose a spell that doesn’t exist, you lose more stamina than any actual spell option, and sometimes the time you waste can cost you in injuries or even death. The game books are designed to be played even if you don’t have the spell book, so there is always a non-magical option. They were kind enough to flag the six most common spells, so that if you memorized nothing else, you can know those six spells, two offensive, two defensive, and two that manipulate other creatures. Those spells are the most flexible, but also the most costly, so if you can remember more spells, you can gain advantages, but you never suffer penalties if you don’t. All these elements together create a clever design that doesn’t punish you for being lazy (or not caring), rewards you for putting in the effort, and has a sliding scale for how much you can memorize so that it is challenging without being daunting no matter what your skill. I made a few mistakes that cost me (I forgot the levitation spell required a jewel-studded medallion!), but never fell for a spell that didn’t exist, and felt damn clever about it. The adventure itself, The Shamutanti Hills, is really well done. I was expecting something close to the Choose Your Own Adventure books, which I did read plenty of when I was a kid. I enjoyed those books, but I was often frustrated by the drastic turn that harmless decisions could make. (All I decided to do was talk to the old man and I somehow ended up dead?!) By introducing stats and die rolls, the Fighting Fantasy books avoid these surprise catastrophic twists (for the most part) because there are ways for the reader/player to absorb the danger and decide which risks are worth taking. The entries themselves are pretty short, so you get the fictional details and are given a set of choices. Each step is pretty incremental so the story doesn’t take large leaps very often. And when danger comes, you have a Skill stat, which tells you how good you are at fighting, a Stamina stat, which lets you measure how much you can endure before exhaustion and death, and a Luck stat, which lets you take chances and push your luck to a greater effect at a greater risk. It surprised me how much was gained by including these simple stats to the game. Skill goes up and down rarely. You use the stat for combat, and if you lose your sword (which I did), your Skill might be drastically reduced until you can replace your weapon (it cost me my character’s life when he got into a fist fight with a wolfhound in the night), but other than that, it’s pretty steady. Stamina is a kind of Hit Points, and it goes up and down a lot. In this particular game book, you are on a journey and you have to keep track of your provisions and rest. If you go a day without eating, it takes a toll on your stamina. If you go a night without sleeping, that too hurts your stamina score. Getting hurt in combat and casting spells also reduce the score. Eating, sleeping, and healing methods can increase your stamina. My favorite stat, mechanically speaking, is Luck. You begin the game with a d6+6 of Luck (so 7-12). Every time you “test your luck,” you roll 2d6. If you get your luck score or lower, you succeed in the test and get whatever benefit you’re looking for. But after each test, you have to reduce your luck score by one. It doesn’t take long to take a decent Luck score to become a true gamble, and I love the simplicity of the mechanic and the curve of difficulty. You’re probably safe for the first couple rolls if your stat starts high, but soon, you sweat it. In addition to those stats, as I said, you’re keeping track of other things. This particular book has you on a journey through wilderness, so keeping track of your provisions is important. You also have a supply of gold which you can use in the various towns to get a safe night’s sleep or buy new provisions, and sometimes equipment too. You also keep a list of your supplies, so you know if you have spell ingredients or things to bargain with. In addition, you have a box on your character sheet for keeping track of “bonuses, penalties, curses, etc.” I was surprised what this little box did for a solo adventure game. Because you can keep track of things, the fictional events in the book can easily have lasting repercussions. At one point I entered a town suffering from the plague and contracted the disease. As a result, every morning I had the disease, I had to reduce my stamina by 3. So even though the entries of the story never brought up my disease, I had to face it in the fiction in my head. How cool is that? The book didn’t have to do all the work because there were stats and a place to keep notes. The last little mechanical thing that is really cool is that you are allowed one bequest from your god, Libra. At any point in the story, you can call on your god, even if the entry you’re at doesn’t give you the option, to revitalize all your stats (put them all at their starting value) or remove a curse or disease. Moreover, at certain points in the book, the list of options includes praying to your god for a miraculous escape from an impossible situation. But you can only use the bequest once, so choose wisely. It’s a neat get-out-of-jail free card and it made the game more enjoyable to have that in your pocket. I used mine when I was in the climactic labyrinth and found myself about to drown without recourse. I had forgotten about it when I was suffering from the plague, but I was glad I didn’t use it before I really needed it! Those are the simple mechanics, and they raise the Fighting Fantasy books so far above the Choose Your Own Adventure books that I can’t even see them from here. The story structure is well done too. In Shamutanti Hills, you are heading on the first part of your quest through the titular hills. The journey takes (not that you know this at the beginning) five days, and the narrative is structured by those day breaks, so that no matter what adventure paths you take, all readers will be at the same place at the end of the third day, the end of the fourth day, and the end of the adventure (assuming they survive, of course). Each day has a number of paths so that you will have one major encounter no matter what path you take, and how much you want to engage in that encounter is mostly up to you. Sometimes you’re in the thick of it whether you want to be or not, but usually when you play it safe, the book lets you have low stakes in your adventure. Of course, the rewards are commensurate with the risk, but the option is always yours. I particularly love that there are separate adventure paths even within paths so that you can play the adventure many times and have radically different experiences. If, for example, you end up in the Goblin caves (instead of the Elvin village or running into the Headhunters), you may encounter an ogre, or a goblin boss or a cave-in. When you finish that particular encounter, the story puts you back on the road to your journey, so there is no way to see everything. The only way I know about all these possible paths is that I made a chart of every path because I was curious to see how the game was structured. As you would think, the possibilities are great at the start of the game and narrow as you work your way toward the end, so that everyone end up in the same climactic scene no matter where they go (assuming again that you survive). To make your specific path meaningful, the designer put in a bunch of referential items and passages so that you can have these Aha! moments. For example, if you buy an axe from a merchant in the first village, you can find the creator of that axe in the fourth village and return it to him for information and gifts. Or you can find a key in the goblin caves and find the cage that it opens later in the adventure. Cooler still, because the book was written as part of a four-book series, your specific adventures here in book one will affect things in book two! For example, if you spare the assassin his life, he’ll offer you something special in the city you are headed to, and you are given an entry number to check out once you arrive in that city in book two to meet up with the assassin and get his assistance. Or a character might tell you to call on his friend when you get to the city and give you his three-letter name, so that when that name appears in a spell list in the second book, if you choose it, you call on his friend. These little moments, simple as they are, make the world feel large and full of life. As you can tell, I was impressed by my experience. I played the book more as a study than for play itself and found myself having a great time and tickled by what the art form could do. The writing is direct and descriptive, which is just about perfect. Nothing too flowery, but I could always get a sense of space and environment. The only disappointment in the book is the horrible racist portrayal of the headhunters. They are bad, bad, bad, and I would love to see them stricken from the book. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed