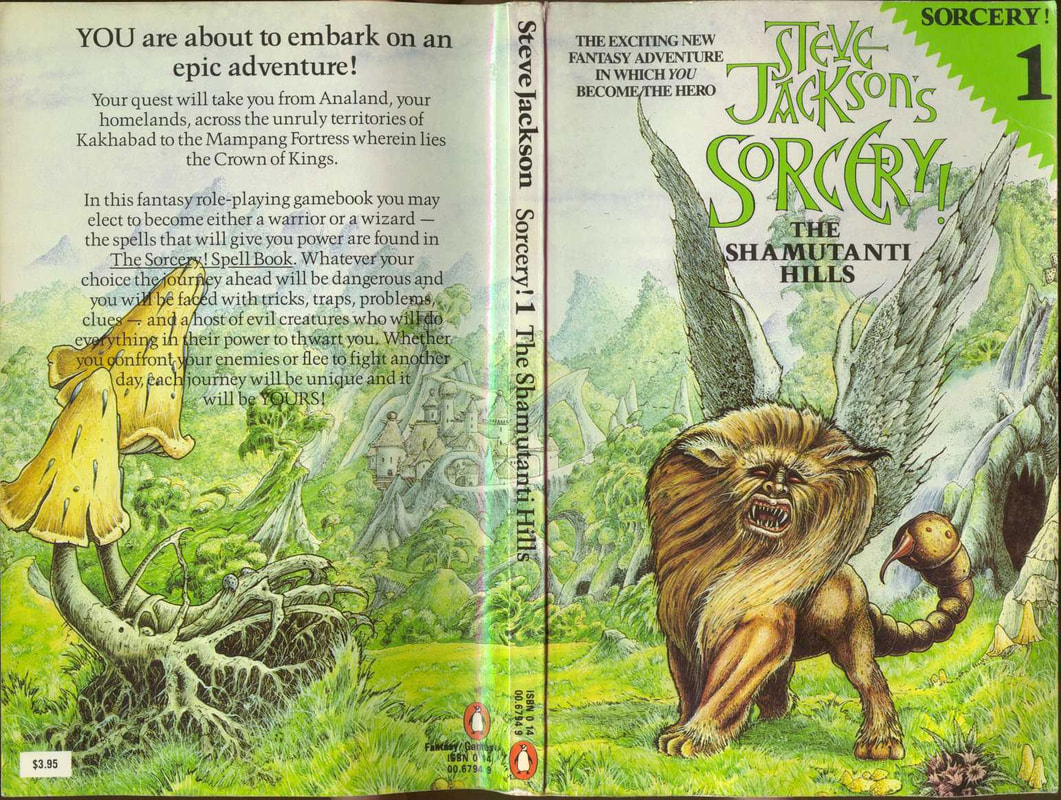

I never read the Fighting Fantasy books when I was young, didn’t even know they existed. I first learned about them in the last three years as I’ve been digging into RPGs and narrative games. For plenty of game designers, these solo adventure books were early inspiration, and having finally read one of them, I can understand why. I decided to start with the Sorcery! Series because I didn’t intend on reading a lot of these books and I remember reading about this particular series on Vincent Baker’s “anyway” blog when someone in the community brought it up in a discussion about magic systems. When someone brought it up again the other day, I decided it was a sign to dive in. The trick of this specific set of five books is that you play a sorcerer (surprise!) with a spellbook of 48 spells, only it is unsafe to bring the spellbook on your journey, so you have to have your spells memorized when you play. Each spell has a three-letter name, which is related to the nature of the spell, some closely related, other more obscurely. The fireball spell, for example, is HOT, and the lightning bolt spell is ZAP. DOZ lets you slow down an attacking creature to one-sixth its regular speed. Of course, you might forget and think it’s a sleep spell. Some spells don’t require anything other than your stamina (one of your character’s stats in the game), while others require a general or specific ingredient. One spell, for example, requires sand, while another needs a Bracelet of Bone. The Sorcery Spell Book lists all 48 spells roughly in order of relevance, each with a picture; the name of the spell; a description of the spell, its limitations, and any ingredients required; and the cost to your stamina to cast it. It’s a simple, but nicely designed book. While it sucks that you have to shell out the extra money for it if you want to play a wizard in the regular game books, it’s a neat little artifact and makes it easy to not cheat, if you want to follow the rules of the book. When you come to an entry in the game books in which you are asked if you want to cast a spell, the book gives you five of the three-letter titles, but not all of the options are real spells. So you need to know, which spell you want to cast, what it’s called, if you have enough stamina to cast it, and if you have any ingredients necessary for the casting. When you make a wrong choice, you have to spend the stamina anyway, so it can be costly to make a mistake. If you choose a spell that doesn’t exist, you lose more stamina than any actual spell option, and sometimes the time you waste can cost you in injuries or even death. The game books are designed to be played even if you don’t have the spell book, so there is always a non-magical option. They were kind enough to flag the six most common spells, so that if you memorized nothing else, you can know those six spells, two offensive, two defensive, and two that manipulate other creatures. Those spells are the most flexible, but also the most costly, so if you can remember more spells, you can gain advantages, but you never suffer penalties if you don’t. All these elements together create a clever design that doesn’t punish you for being lazy (or not caring), rewards you for putting in the effort, and has a sliding scale for how much you can memorize so that it is challenging without being daunting no matter what your skill. I made a few mistakes that cost me (I forgot the levitation spell required a jewel-studded medallion!), but never fell for a spell that didn’t exist, and felt damn clever about it. The adventure itself, The Shamutanti Hills, is really well done. I was expecting something close to the Choose Your Own Adventure books, which I did read plenty of when I was a kid. I enjoyed those books, but I was often frustrated by the drastic turn that harmless decisions could make. (All I decided to do was talk to the old man and I somehow ended up dead?!) By introducing stats and die rolls, the Fighting Fantasy books avoid these surprise catastrophic twists (for the most part) because there are ways for the reader/player to absorb the danger and decide which risks are worth taking. The entries themselves are pretty short, so you get the fictional details and are given a set of choices. Each step is pretty incremental so the story doesn’t take large leaps very often. And when danger comes, you have a Skill stat, which tells you how good you are at fighting, a Stamina stat, which lets you measure how much you can endure before exhaustion and death, and a Luck stat, which lets you take chances and push your luck to a greater effect at a greater risk. It surprised me how much was gained by including these simple stats to the game. Skill goes up and down rarely. You use the stat for combat, and if you lose your sword (which I did), your Skill might be drastically reduced until you can replace your weapon (it cost me my character’s life when he got into a fist fight with a wolfhound in the night), but other than that, it’s pretty steady. Stamina is a kind of Hit Points, and it goes up and down a lot. In this particular game book, you are on a journey and you have to keep track of your provisions and rest. If you go a day without eating, it takes a toll on your stamina. If you go a night without sleeping, that too hurts your stamina score. Getting hurt in combat and casting spells also reduce the score. Eating, sleeping, and healing methods can increase your stamina. My favorite stat, mechanically speaking, is Luck. You begin the game with a d6+6 of Luck (so 7-12). Every time you “test your luck,” you roll 2d6. If you get your luck score or lower, you succeed in the test and get whatever benefit you’re looking for. But after each test, you have to reduce your luck score by one. It doesn’t take long to take a decent Luck score to become a true gamble, and I love the simplicity of the mechanic and the curve of difficulty. You’re probably safe for the first couple rolls if your stat starts high, but soon, you sweat it. In addition to those stats, as I said, you’re keeping track of other things. This particular book has you on a journey through wilderness, so keeping track of your provisions is important. You also have a supply of gold which you can use in the various towns to get a safe night’s sleep or buy new provisions, and sometimes equipment too. You also keep a list of your supplies, so you know if you have spell ingredients or things to bargain with. In addition, you have a box on your character sheet for keeping track of “bonuses, penalties, curses, etc.” I was surprised what this little box did for a solo adventure game. Because you can keep track of things, the fictional events in the book can easily have lasting repercussions. At one point I entered a town suffering from the plague and contracted the disease. As a result, every morning I had the disease, I had to reduce my stamina by 3. So even though the entries of the story never brought up my disease, I had to face it in the fiction in my head. How cool is that? The book didn’t have to do all the work because there were stats and a place to keep notes. The last little mechanical thing that is really cool is that you are allowed one bequest from your god, Libra. At any point in the story, you can call on your god, even if the entry you’re at doesn’t give you the option, to revitalize all your stats (put them all at their starting value) or remove a curse or disease. Moreover, at certain points in the book, the list of options includes praying to your god for a miraculous escape from an impossible situation. But you can only use the bequest once, so choose wisely. It’s a neat get-out-of-jail free card and it made the game more enjoyable to have that in your pocket. I used mine when I was in the climactic labyrinth and found myself about to drown without recourse. I had forgotten about it when I was suffering from the plague, but I was glad I didn’t use it before I really needed it! Those are the simple mechanics, and they raise the Fighting Fantasy books so far above the Choose Your Own Adventure books that I can’t even see them from here. The story structure is well done too. In Shamutanti Hills, you are heading on the first part of your quest through the titular hills. The journey takes (not that you know this at the beginning) five days, and the narrative is structured by those day breaks, so that no matter what adventure paths you take, all readers will be at the same place at the end of the third day, the end of the fourth day, and the end of the adventure (assuming they survive, of course). Each day has a number of paths so that you will have one major encounter no matter what path you take, and how much you want to engage in that encounter is mostly up to you. Sometimes you’re in the thick of it whether you want to be or not, but usually when you play it safe, the book lets you have low stakes in your adventure. Of course, the rewards are commensurate with the risk, but the option is always yours. I particularly love that there are separate adventure paths even within paths so that you can play the adventure many times and have radically different experiences. If, for example, you end up in the Goblin caves (instead of the Elvin village or running into the Headhunters), you may encounter an ogre, or a goblin boss or a cave-in. When you finish that particular encounter, the story puts you back on the road to your journey, so there is no way to see everything. The only way I know about all these possible paths is that I made a chart of every path because I was curious to see how the game was structured. As you would think, the possibilities are great at the start of the game and narrow as you work your way toward the end, so that everyone end up in the same climactic scene no matter where they go (assuming again that you survive). To make your specific path meaningful, the designer put in a bunch of referential items and passages so that you can have these Aha! moments. For example, if you buy an axe from a merchant in the first village, you can find the creator of that axe in the fourth village and return it to him for information and gifts. Or you can find a key in the goblin caves and find the cage that it opens later in the adventure. Cooler still, because the book was written as part of a four-book series, your specific adventures here in book one will affect things in book two! For example, if you spare the assassin his life, he’ll offer you something special in the city you are headed to, and you are given an entry number to check out once you arrive in that city in book two to meet up with the assassin and get his assistance. Or a character might tell you to call on his friend when you get to the city and give you his three-letter name, so that when that name appears in a spell list in the second book, if you choose it, you call on his friend. These little moments, simple as they are, make the world feel large and full of life. As you can tell, I was impressed by my experience. I played the book more as a study than for play itself and found myself having a great time and tickled by what the art form could do. The writing is direct and descriptive, which is just about perfect. Nothing too flowery, but I could always get a sense of space and environment. The only disappointment in the book is the horrible racist portrayal of the headhunters. They are bad, bad, bad, and I would love to see them stricken from the book.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed