|

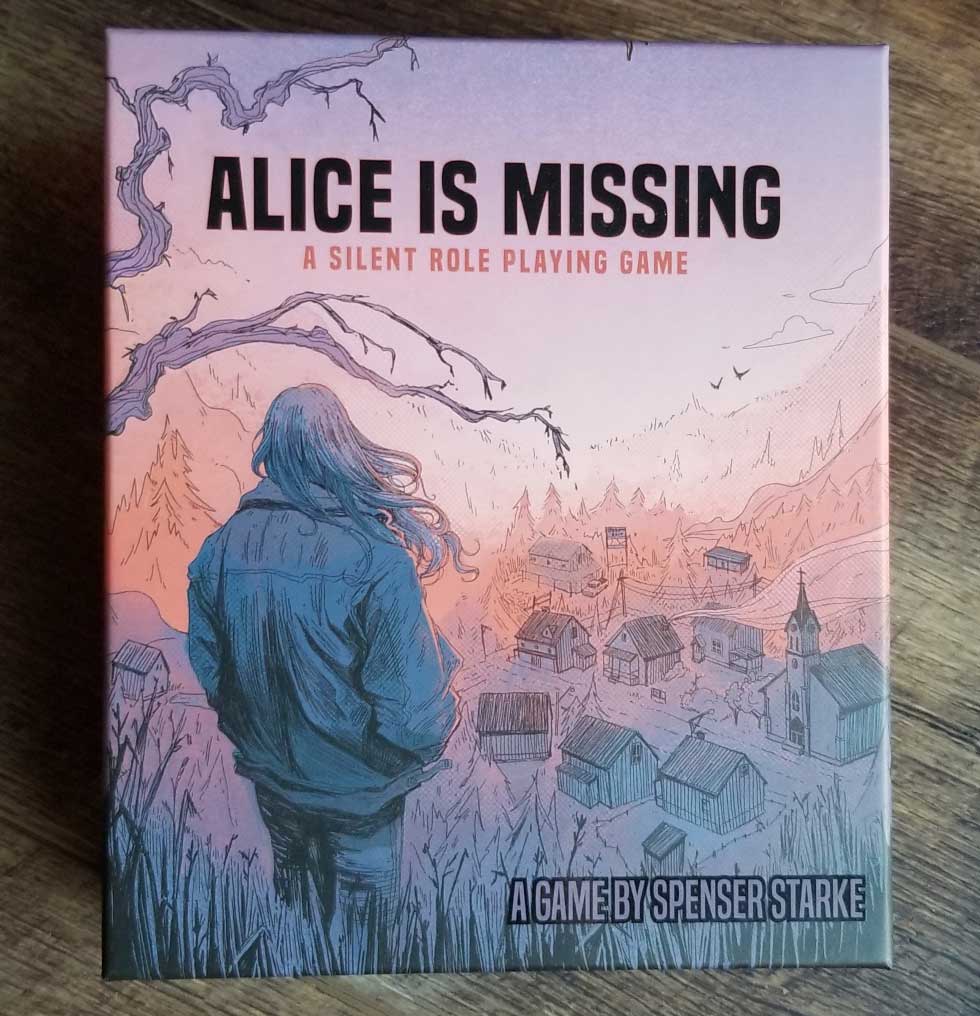

I backed Alice Is Missing on Kickstarter, and my copy arrived only yesterday. While I didn’t follow the Kickstarter closely after I backed it, I was eager to read the details of the game to learn how it worked. It’s a neat silent larp, in which all the players play their characters through a phone chat group as they investigate (or just talk about) the disappearance of their mutual friend, Alice Briarwood. Tonally, Starke took inspiration from Life is Strange, Gone Home, and Oxenfree. Please note that I have not played the game yet, only read it thoroughly and imagined play. The quality of the game pieces is excellent. The box is sturdy and the box art, by Julianne Grepp, gorgeous. The bulk of the game is a set of 70 or so tarot-sized cards, which are beautifully done and printed on high-grade stock. I like to sleeve my game cards, and by removing the box insert, I am able to store the whole game in the original box even with the sleeved cards, which is a nice feature. The rulebook is stylishly laid out, easy to read, and on good paper. There is one odd quirk about the rulebook: it gives you most of the information you need twice. The first 22 pages of the booklet is a summary of everything you need to know to run the game. The final 26 pages are the “Facilitator Guide,” which is designed to walk you through the steps of being the facilitator, but essentially repeats everything from the first 22 pages. The main motivator seems to be the desire to give the facilitator a step-by-step guide to setting up and running the game, including sample passages to read to the players at each step of the game. The impulse is laudable, but the final execution makes for an inelegant and awkward read. The game itself looks cool and fun. The first part of play is character creation and setting the narrative stage. From the printed-out stack of missing-person posters, you randomly pull who your Alice is for this game. Once this is known, each player takes one of the five character cards. The only required character is Charlie Barnes, “The one who moved away,” which the facilitator always plays. Charlie had moved away from Silent Falls, the small Northern California town where our story takes place, and has recently returned to live with his father. The character card tells you your name and your relationship with Alice (best friend, older brother, secret girlfriend, and one with a crush). To this bare-bones information, each player gets a Drive Card, which gives you a basic way to behave, such as: “you fear the worst for Alice. Jump to conclusions, make conspiracy theories, and blame yourself for her disappearance”; or “you want to keep everyone calm. Crack a joke, distract from the chaos, do everything to can to bury your true fear.” With this basic sketch of your character, you begin to flesh out who Alice was by answering the prompt included on your character card. For example, “What kind of teenager is Alice? (Quiet, Jock, Popular, Valedictorian, Stoner, Etc.)”; or “What about Alice do other people sometimes find annoying but you appreciate?” Once Alice is sketched out, you return to your Drive card and use the prompts there to form your character’s relationship with two other player characters. One card offers these two relationships: “I know how you really feel about Alice” and “We’ve never gotten along.” Another has these two: “I don’t think you like me,” and “I’ve always wanted you to be my friend.” All of these prompts are well chosen to give strong starting situation. You get everything you need to know to start moving ahead while still having plenty of room to create characters and fuller relationships through play. The two cards—the Character Card and the Drive Card—do a lot of heavy lifting in a quick and easy fashion. In addition, there is enough here to create replayability, though the game suggests not playing with the exact same group, which seems reasonable. The final step of character/world creation is to look at the 5 suspects and 5 locations that will recur throughout the game. Having laid out the cards in two rows, the players take turns picking one of the cards and explaining why that person or place is suspicious in Alice’s disappearance. This is a clever way to introduce everyone to these recurring features of the narrative and to give everyone a reason to be wary of them. Naming all the ways the world and people around us are dangerous and unknown has an additional psychological impact, placing the players in a shared mood and mindset. After you have used the cards to create your characters and their world, you are ready to play out the mystery of Alice’s disappearance. The mystery takes place over 90 minutes, with a countdown clock available for download or on Youtube. The countdown video comes complete with a soundtrack. Since no one will be speaking, the music should have a significant impact on the mood during play. The facilitator has a stock message to send the group chat at the start of the 90 minutes, the narrative reason for us all to be chatting in the first place. Then clues are uncovered by different players at predetermined times via Clue Cards. One appears when the countdown hits 80 minutes, another at 70 minutes, then 60 minutes, then 50, then 45, 40, 35, 30, 20, and finally the climax hits at 10 minutes, with the flurry of texting and the final fallout wrapping before the clock hits zero. Each clue has you reveal a suspect or a location from their respective decks and prompts you to create a bit of narrative the implicates them. At some point one of the revealed suspects becomes THE suspect and one of the revealed locations becomes THE location. The clue cards are a clever way to control pacing, as the prompts begin by creating rumors and slowly bring the suspects and their threats closer and closer to our characters. You see that at the center of the game, the clues come every five minutes so that revelations come fast and furious. In a 5-person game, each character will have something big to contribute to the conversation from minute 50 to minute 30. Overall, the prompts are as solid on the clue cards as they are on the character cards. Some prompts make heavier narrative demands on the players than others, but there were only one or two prompts that I found intimidating, especially if I had to create it while getting texts from others and trying to figure out how to impart the information organically. Most of them ask for simple but effective bits of story. For replayability, there are three clue cards for each countdown time, so each game you play will have different prompts. Up to this point, I tried to be as specific as I can without spoiling any specifics about the story elements. From here forward, however, I’ll need to spoil the story in order to discuss the games limits and to talk about it thematically and politically. *Spoilers ahead! Turn back now if you don’t want to know the story content of the game.* Starke has to perform a balancing act between the narrative possibilities of the story and the speed and ease of setup. Alice will always have been taken by one of the 5 suspects in some twisted or malevolent plot. Even though Gone Home is an inspiration, you do not have the possibility of a lover’s elopement. Similarly, none of the 3-5 players can have had any roll in Alice’s disappearance. To allow for all or any of these possibilities would mean all kinds of development during character and world creation and radical changes to the clue card prompts. Or, at least I think it would. At the very least, it would need to allow for a much wider range of 10-minute cards. As it is, it’s cool that Alice could be in any state of health, and it’s cool that one of the players will become tied up with Alice’s fate, but I’m greedy, and seeing something awesome often makes me want to see it even more awesome. The ramifications of these limits go beyond aesthetics. In the end, you will always tell the tale of a high school girl who was kidnapped/lured/entrapped/misled by a hostile member of the community: an authority figure, an ex, a rich kid (which I think “popular” always means), a bully, or a creeper. The authority figure and rich kid will always point to the powerful, but bully, creeper, and ex are unmoored. These could easily be the poor or disenfranchised of the community, especially since the player’s biases are not given any checks by the mechanics of the game. All of this means that the game is open to repeating harmful tropes and storylines. Putting in checks to these impulses or cutting off certain possibilities wouldn’t be too hard to do, but those adjustments are better made at the design level than hacked by the players. Along these same lines, Alice is a unambiguously gendered name, which means that we are repeating a tale of violence against women without any opportunity to tell a different story. Other names are ambiguously gendered allowing for the full range of pronouns and relationships. I’m not sure if this is harmful or problematic, but I think it is unnecessarily limiting. Regardless of these limitations and possible problems, the game is focused and well-designed. It’s one of the few larps that I feel can easily pull me into larping. It would make a fantastic introduction to the hobby.

1 Comment

|

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed