|

There were several reasons compelling me to pick up a copy of TSR’s 1996 DragonLance Fifth Age game. The original trilogy of novels holds great nostalgic value for me. While I don’t think I ever played any of the D&D modules from the ‘80s, I owned a few and enjoyed reading them. I’m also a sucker for card games and love to see how RPGs utilize cards instead of dice. That this game used a custom deck was all the more intriguing. And finally, I heard great things about the expression of the fate deck in the Marvel version of the system and wanted to be able to compare the two iterations. All these things sent me to ebay to hunt down a reasonably-priced edition of the boxed set. While my excitement was high, my expectations were actually quite low. I am entirely immersed in the indie side of TTRPGs and have been for six years. Neither D&D nor fantasy games call to me these days. I expected to dig through the rules and find a gem or two worth admiring. To that end, I was glad to see that the main rule book is digest-sized and a mere 128 pages. But what I found there surprised and delighted me well beyond my expectations. Many parts of the game’s rules and design read as early iterations of ideas the indie design scene worked on throughout the first decade of this century. First, the GM and their characters don’t engage directly with the mechanisms of play and resolution. If an NPC attacks or acts on a PC, then the game looks to the PC’s reaction to determine the success or failure of that NPC’s action. We see this today in games like Apocalypse World, where the MC doesn’t roll dice, facing all the mechanical interactions toward the players. Apocalypse World does so (in part) to center the PCs as protagonists, putting them in the driver’s seat of the narrative as it unfolds. While DragonLance Fifth Age still positions the GM, literally, as the “Narrator,” giving the Narrator the responsibility of the “plot,” an unfortunate convention that the game does not escape, the designers specifically center the PCs as actors and reactors because they are “heroes,” and regardless of what happens within the narrative, it is their story. To describe the other early inventions at the core of this game, I need to take a moment to explain its central mechanics. At the heart of play is the Fate Deck. The Fate Deck is made up of 8 suits with values 1 through 9, and a ninth suit with values 1 through 10, making the deck of total of 82 cards. Each of the main suits correspond to an “ability” score on the PC character sheet. The ability are split evenly between physical and mental abilities, and then halved again within each of those divisions. So the physical abilities are divided into coordination and physique, and the mental abilities are divided into intellect and essence. Coordination is made up of agility and dexterity, physique is made up of endurance and strength, intellect is made up of reason and perception, and essence is made up of spirit and presence. While each of those 8 abilities can be used as the basis of a character action, they are paired up so as to be active and reactive. For example, if you are making an attack with your sword, you will use your strength; if you are responding to an attack by an enemy wielding a sword, you will use your endurance. Likewise, if you are using you are making a magical attack, you will use your reason; if you are resisting a magical attack, you will use your perception. Each of these abilities will have a starting value of 1 through 10, with 5 considered the human average. Players have a hand of cards at any time, all drawn from the same Fate Deck. The size of their hand is determined by their “reputation,” which represents their experience as heroes. The more experienced the hero, the more resourceful they are. Starting characters often give their players a hand size between 2 and 5 cards. When a player declares that their character is taking an action, and the Narrator says that such an action has the potential for failure, they turn to the cards. First, they determine what suit is appropriate for the action. Climbing a wall might require strength. Moving across a narrow ledge might require agility. Then the Narrator determines a difficulty rating for the action. The difficulties range from easy to impossible, and they move in 4-point increments. So an easy action requires a 4, an average action an 8, a challenging action a 12, all the way up to an impossible action requiring a 24. The player than plays one card from their hand, adds the value of that card to their ability score, and compares that totaled number to the difficulty number. If they meet or exceed the difficulty rating, they succeed in their action. So, if a player’s character has an ability with a score of 8, they can succeed in an average action without playing any card. When an action is opposed, then the difficulty rating is beefed up by the ability score of the thing opposing the action. So let’s say you’re fighting an ogre. Swinging your sword is an easy action, giving it a difficulty rating of 4. But an ogre’s physique ability is 13, so that gets added to the 4, giving you a total of 17 to hit and damage the ogre. If you have a strength of 9, you’d better have an 8, 9, or 10 in your hand to land that blow. And when the ogre swings at you, you can try to dodge his club, which is an easy action, again a 4, which is added to the ogre’s 13, again giving you a target number of 17. Now you look at your agility score (for dodging) and play a card to add to it. The final element to consider in these actions is the suit of the card you played. It the suit of the card matches the ability you are using to make your action, then that suit is considered trump and you get a bonus. In the examples above, if you play a card of the strength suit to hit the ogre, or the agility suit to dodge the ogre, you have played trump. When you play a trump card, you get to flip over the top card of the Fate Deck and add the value of that card to your action’s total. Better yet, if the flipped card is also trump, you can flip the next card as well, and keep doing so until you hit a non-trump card. This method allows characters to achieve seemingly impossible tasks, although the odds are never in their favor. Still, if you have the 9 in your trump suit, you will draw an average of 4.5—let’s just call it a 4, which means that you have 13. If your basic ability is high, you can get just shy of impossible at 24. You may have noticed that I haven’t yet spoken of the ninth suit, the one that doesn’t correspond to an ability score. That suit is the suit of Dragons. It offers more power by going higher than all the other suits, to 10, but it also threatens to harm you. If trump allows for critical successes, then the Dragon suit allows for critical failures, or what the game gently calls a “mishap.” When you fail an action in which you played a card of the Dragon suit, the Narrator is given permission to make your failure particularly painful. Whenever you play a card, you immediately draw a new card, so you won’t run out of cards by taking actions. Bigger hands of cards help by giving you more options and access to greater odds of having a high card or a trump card in the action you’re taking, or to avoid being forced to play a Dragon card when failure looms, which is how hand size represents experience and resourcefulness. To return then to the innovations of the game, now that you understand the basic mechanics, actions are essentially player-facing moves, reminiscent once again of Apocalypse World. The rule book lists a number of common actions, such as breaking down a door, telling a convincing lie, picking a lock, or intimidating someone. When such a thing happens in the fiction, the players can turn to the move, see the typical difficulty, the typical ability used, the opposing ability if there is one, and the common fallout from mishaps. The players are taught by the rulebook how to create their own actions, and adventure-specific actions come with each published adventure, just as an MC for Apocalypse World will create custom moves for locations or certain NPCs. I was stunned by the similarities. Of course, the actions in DragonLance are restrained by the idea that they can only denote success or failure, so actions are inherently less interesting and playful than Apocalypse World moves, which are interested in branching narrative paths that come out of any given move. The other important difference is that Narrator’s are encouraged to keep hidden from the players the specific difficulty rating for the specific action at hand, whereas the targets and results of moves are apparent to all players. This hidden information is intended to spice up gameplay by keeping players on the edge of their seat to know if they put forth enough effort to succeed at their task. That doesn’t particularly appeal to me, but I can easily see how looking at your hand and seeing that you will either succeed or fail before a card is even played can suck the wind out of a moment of resolution. Another cool achievement by the DragonLance designers is doing away with hit points altogether to measure your heroes health. Instead, the designers take advantage of the affordance that the hand of cards provides. When a hero sustains an injury, they must discard from their hand cards that total up to the damage taken. These discarded cards are not redrawn until the character can heal up. When a player has zero cards in their hand, the character is out of commission, passed out, dying, whatever. This makes for interesting choices and a cool kind of death spiral in play. If you need to discard 8 points of cards, and you have, say, 5 cards that are 2, 2, 4, 4, 8, you have a tough decision to make. You can lose the 8, only be down one card, but have a fistful of mediocrity; you can ditch the two fours, keep three cards, one that is good and two that are woefully unimpressive; or you can throw the two twos and a four, be down three cards but have a strong card and a medium card left for the fight ahead. The fewer cards then restrict both your ability to achieve and your ability to resist. This feature reminds me of nothing so much as the dice penalty for injuries you see in Ron Edwards’s Sorcerer. Bad wounds can have long and serious effects. The cards mean that you can also stop keeping track of gold and silver coins. DragonLance is not about delving in dungeons and scrounging for money. It’s about heroics. So instead of a place to count your currency, you have a wealth score that you can use like any other ability when attempting to buy things, like you see in Burning Wheel. All of these achievements are impressive, I think, because they show that the designers knew what they wanted the game to be about and shaped their mechanics and procedures to reinforce that. The pressure to follow traditional design is always strong, but I can imagine it was even more so for a fantasy game, especially one that began its creative life as a D&D module. I could go on and on. I didn’t touch the magic system, which attempts to allow wizards and spiritualists to create extempore spells. I didn’t talk about the elegance and ease of using weapons and armor in combat, keeping the math simple. I didn’t talk about how all this simplicity allows the main rule book to include a 15-page bestiary (on digest-sized pages, remember) that covers just about everything you need. I didn’t talk about the way the cards are used to help the Narrator get quick answers to questions about smaller things that the Narrator wants to declaim responsibility for but that the table still needs to know. It’s not a perfect game by any stretch of the imagination, but it’s a thoughtful game, a well-designed game, a focused game.

2 Comments

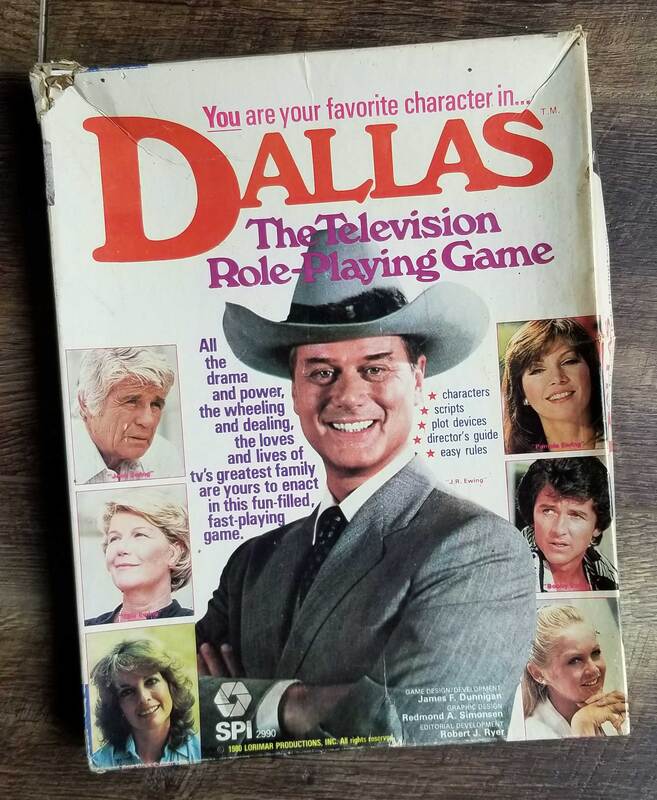

I picked up Mothership moved entirely by the hype surrounding it. I’m a big fan of the inspirational source material behind the game, and the entry cost is eminently reasonable, even for a printed copy of the zine-sized text. But alas, the game is not for me. As a game coming out of the OSR movement, it’s not badly designed. The rules for skill checks, advantages and disadvantages, panicking and combat all appear to be serviceable. At the same time, they don’t have anything particularly unique to say. Combat has the standard elements: determining surprise, rolling for initiative, having limited actions you can make on your turn, making an opposed roll to hit. It adds on stress and panic, like bringing Call of Cthulhu and D&D together, and the two features are yoked together pretty well, but that’s about the only part of the game that involves horror. There is no particular vision about what horror in space is about, what it is in the larger genre that makes it compelling. There is no reading or interpreting of the genre, just the standard game parts bolted onto one chassis. To me, the most compelling part of the text is the art, which does a wonderful job of setting a tone and presenting a vision more unique than the mechanics of the game illustrate. This version of the game is only half complete, I know that. In fact, the full game is being Kickstarted even now. But where the designer is comfortable leaving holes indicates what the designer feels can be handwaved without affecting the central concerns of the game. If the elements were essential, they would be integrated with the rest of the design. Take money, for example. We are told that “everything in Mothership from fuel to food to weapons and ammunition costs Credits.” This makes it sound like Credits is a central driver and economy of the game. But then the rest is handwaved. You get a list of jobs you can do, adventure seeds, but nothing else is developed, presumably because the eternal hunt for more Credits is an excuse for getting the PCs into trouble and then making them return to trouble session after session. The game borrows the aesthetics of truckers and blue-collar workers in space, but that’s as deep as it goes. It’s window dressing. It happens to be loveable and groovy window dressing, but window dressing all the same. Horror and Sci-Fi genres, individually, are each rich and roomy genres, with space to make observations and declarations about our world and our humanity. Mothership is a missed opportunity. I didn’t know what to expect from Dallas: The Television Role-Playing Game. I had heard some people say that it was more of a board game than a roleplaying game. Others said it had some innovative mechanics and was actually fun to play. Still others just dismissed it as a weird tangent to the hobby, not part of the larger movement of design and play. I found a cheap and battered, but complete, copy on ebay a while back and finally got to read it. I found the design of the game to be surprising and exciting, personally. I was too young to be a fan of the show, so there’s nothing nostalgic in my excitement. I haven’t gotten a chance to play it, and I doubt that I will, but it has given me a lot to think about. First, there are indeed characters you play during the game. The character sheets provide all the relevant stats for 9 major characters of the show. Each character has numbers Power, Persuasion, Coercion, Seduction, Investigation, and Luck. Power and Luck are single numbers representing the character’s ability to exert influence and escape consequences, respectively. The other four stats correspond to the main actions each character can take, and they come with both an offensive and defensive number, measuring their ability to be persuasive, say, and resist persuasion themselves. The character sheets for each character are almost identical, each sheet show all the major characters’ stats on the front of the sheet, and all the rules succinctly stated on the back. The only difference between the sheets is that the character’s specific stats are placed in bold at the top of the sheet, a brief summary of their character and background in the show is given, and the “Personal Victory Conditions” for each of the three scripts included with the game. Let’s talk about those scripts and those “Personal Victory Conditions.” Scripts are equivalent to adventures or modules in other roleplaying games, or variants and situations in board games. Each script gives you a fictional situation for the game, with a specific setup, a list of which major characters are involved, what minor characters and what plot devices will be in play. Each script is like an individual TV episode, with its own beginning, middle, and end. At the start of play, the Director gives a general setup for the fiction of the story. Then, in private, the director gives each player the specific story and goals of their major character. The game then plays out in five or fewer scenes, and at the end, any player who met their personal victory conditions is considered a winner. Personal victory conditions all involve “controlling” a number of assets—those minor characters and plot devices I mentioned earlier. Minor characters, plot devices, and organizational characters (characters with official titles but not individual names—so, an FBI agent, a Texas Railroad Commissioner, and so on) are all printed on individual cards. Plot devices are just names: Ellie’s Letters, Spanish Land Grant, Saddlebag full of Krugerrands, Cowboy-Redskins Football Tickets. These are the MacGuffins characters are fighting over to control. The minor and organization characters come with stats for all the major actions of the game so they can properly assert and resist persuasion, coercion, seduction, and investigation. Some of these cards begin the game on the table face-up, so everyone knows that they are in play; some begin face down, known to some and not to others, driving those players who are not in the know to investigate to find out who these pawns and powers are; and some are brought in by the Director during the game to introduce new developments and tensions. As I indicated, play progresses through scenes. Each scene consists of a number of phases. First, in the Director Phase, the Director gives out information to the group and to individual players, possibly handing out new minor characters or plot devices. This is just an information phase, but that information can easily tilt the landscape of play. The Director also sets up how long the Negotiation Phase, the phase that follows, will be at this time. The Negotiation Phase allows players to talk among themselves and make deals. The players can trade assets (minor characters, organizational characters, and plot devices), form alliances, make plans, and generally agree upon whatever they can. Players are allowed to take other players away from the table in order to make their deals in private. Finally comes the Conflict Phase, in which everyone takes action. You can try to gain control of minor characters by persuading, coercing, or seducing them away from their current allegiance; you can investigate face-down cards to find out what secrets you aren’t in on; you can even attempt to get another major character thrown in jail if it is known that they have committed an illegal act and you have some form or law enforcement under your influence. When the dust settles, the next scene begins with the Director Phase and it starts all over again. At the end of the final scene, you look at what you control and what you need to control to “win” and see how you did. As you can gather from my description, this is a strategic and competitive game. The amount of roleplaying anyone engages in is entirely up to the players involved. It would be easy to play an entire game without once speaking in a character’s voice or building up fictional scenes for your actions. In fact, the one example of play given in the game books shows the players engaging in nothing fictional, focusing entirely on the pieces of play as pieces of play. Nothing in the rules or procedures force roleplaying. But only the focus on achieving your goal might inadvertently stand in your way of actively creating fictional scenes. The rules prohibit the number of actions you can take during the Conflict Phase in order to reflect that what is transpiring is a single scene (or more accurately, I suppose, an act). Your character can only be in one or two places per scene and only affect one character or plot device where they are. So you can easily set up that moment of conflict within the fiction and play it out before rolling the dice to see if you are successful in your act of persuasion or coercion or seduction or investigation. I think it would be quite cool to see that in play. The game immediately put me in mind of Fiasco. Each player has a character driven by their own ambitions and debts, all connected to each other by a web of relationships, fighting over the same limited pool of resources. The plot devices are just “objects” in Fiasco’s language. That Saddlebag full of Krugerrands, for example, could fit into any number of Fiasco playsets. The tone is obviously different, leaning more towards soap than tragicomedy, but the basic idea of play is strikingly similar. Mechanizing the attempts to gain influence over minor characters through persuasion, coercion, and seduction, is a neat idea, and their execution is admirable. Let’s say you are trying to persuade Ralph Bentocher, the senator’s son, to intervene with his father in your interests. You take your offensive persuasion skill (if you’re J.R., that’s 20) and subtract from it your target’s defensive persuasion skill (Ralph, poor soul, only has a 7 to resist), and get a number (in this case, 13). If that number is 0 or 1, you automatically fail. If the number is 12 or higher, you automatically succeed. If that number is between 2 and 11, you roll 2d6 and see if you can roll equal to or less than that number, you succeed. Additionally, your minor characters can work on your behalf, using the same actions, to increase the amount of influence you can exert in any one scene. And you can use your major characters Power score to help give your lackeys a boost in their efforts. So when Ralph talks to his father, the force of J.R.’s name is behind his own roll to persuade. I like it. This is just a side point, but the way the personal victory conditions are described in the various scripts also put me in mind of Fiasco. Here is what J.R. must control at the end of “The Great Claim” script to win: Land Grant The comments give you both flavor and humor, grounding the bits of paper on the table with the fiction of the game. Moreover, it tells you how J.R. thinks and how he manipulates the world. I find their short lists energizing and compelling, making me want to play and engage with the fiction. The game has me thinking about ways to have enjoyable play while major characters have interests pointed directly at each other, where the heart of play is conflict between characters, not in the form or physically battling, but in the form of influence and manipulation. There’s a lot here to feed the mind. If for some reason I was just burning to play a game like a Dallas TV show, I would just create a Fiasco playset, but it would definitely be playing Fiasco in Dallas’s world. There’s one other cool thing I’d like to point to before wrapping up. There is a section in the books that tells you how to create your own character stats, and I think their method is interesting enough to share: In the game, the character Abilities were initially derived through a somewhat abstract process. A character’s Abilities were rendered into six major categories: intelligence, charm, lack of scruples, physical attractiveness, nerve, and power. The ratings were assigned relative to other characters. A 9 is on the high end of the scale, and 1 is the low end, except in the case of power where a character can have zero. Intelligence was evaluated in terms of both intellect and cunning. J.R. was arbitrarily given an 8. In charm, representing the ability to get your own way on the basis of personality, J.R. rated another 8. For lack of scruples, he was assigned another 8 (there are certain things he draws the line at, particularly where his parents are concerned). For nerve, J.R. again rated an 8, as did Pam, Jock, Bobby, and Lucy. For power, J.R. deserved a 9 without question. Two things I want to point to here. The first is that those original stats, the unseen ones, are a perfect breakdown of the descriptors of the characters in the show. To some degree or another, all the characters are intelligent, charming, unscrupulous, attractive, full of nerve, and powerful. To then turn those characteristics into the verbs that are their actions is common enough in roleplaying games, but that step is often left for the players to calculate. You typically determine their stats and use their stats to determine how effective you are at doing a thing. There’s something cool about that happening behind the scenes here. The second thing that I want to draw your attention to is the imbalance of power between characters, which the game embraces without apology. None of the characters have comparable stats. They are not balanced to make sure that Lucy and J.R. have the same chance to do the same things. That’s a bold move, and one RPGs have been wrestling with for a long time. The way Dallas addresses that imbalance is to give each character personal victory conditions in proportion to their character’s ability. Lucy doesn’t need to control nearly as many things as J.R. In fact, some of Lucy’s win-conditions often line up with another character getting what she wants, which means, Lucy can team up with certain characters to each achieve their shared goals. Weaker characters will team up against more powerful characters and alliances will shift as power shifts during the individual games. It’s built to keep play dynamic and interesting. There is no surprise in the fact that I missed this little RPG boxed set when it came out in 1999. I was only an expectant father, and I had missed the Pokemon craze of the 90s entirely. Moreover, the box hung on racks like any other boxed cards sold for CCGs at that time. Nothing on the box tells you that it is an RPG or related to RPGs. I didn’t become aware of the game until earlier this year when someone on the gaming Slack channel I frequent shared pictures and his thoughts. It sounded cool enough to pick up off ebay for $10 and see for myself. The box comes with an instruction booklet, an assortment of Pokemon cards, a d6, checklists of all available Pokemon cards, two tokens for flipping, and a set of counters for tracking wounds. Play is designed to imitate the Pokemon video games, in which a young protagonist is given their first Pokemon by a professor and then they head off across the land to gather more Pokemon and train up their skills. After covering the basic rules, the instruction booklet includes an adventure to walk first-time players and Narrators through the game. The Narrator is the game’s GM. They assume that a parent will play the Narrator to their children and their children’s friends. The designers—who, sadly, are unacknowledged in the booklet—successfully seized on the two things at the heart of the Pokemon video games: exploration and Pokemon combat. The first, exploration, is achieved by the adventure itself, outside of any dictated rules or procedures of the game. The text of the adventure prompts the Narrator to ask questions about the physical world during play. For example, in the first scene, the protagonists go to Professor Oaks lab to get their first Pokemon. The Narrator is told to ask, “The lab is part of a larger building. What does the lab look like?” Also: “There are computers and machines in the lab. What else do you see?” This invitation to the players to partake in the describing and building of the fictional world is a beautiful way to have the children talk about the exciting parts of the world that occupy their imaginations. The players can surprise themselves and each other with their observations, their memories, and their creativity. It leaves room for the adult Narrator to be taught about the world by the enthusiasts in the room (if indeed the parents are not themselves enthusiasts). The adventure itself is impressively long, well beyond the basic opening scene and battle that I expected. The adventure is varied and gives the players different challenges and experiences, and it introduces them to popular characters from the show and game, like Team Rocket, Police Officer Jenny, and Brock. Players catch wild Pokemon, find a rival, and battle a gym master. Pokemon solve non-combat problems. The only disappointment is that Wizards of the Coast never produced the additional sets that were intended to follow this one, with more Pokemon cards and more adventures. Had I had this game when my son was 8, he would have been thrilled to his Poke-loving heart to have played. The combat mechanics are surprisingly elegant, given how complex they could easily become. The price for avoiding that inviting complexity is that you don’t have cool features like Pokemon attack types having special affects on other Pokemon types. But before we look at what’s missing, let’s see what’s here. The Pokemon cards are two-sided. Half of each side is an illustration of the Pokemon. The Pokemon’s Hit Points are in one corner, falling primarily between 7 and 10. Each side shows a different attack move. The attack move has a name, the odds of success, and the amount of damage it does. The odds of success are written as the numbers on a six-sided dice. For example, on one side of one of my Bulbasaurs is a Tackle attack, which succeeds on a 5 or 6, and which deals out 4 Hits. When I declare Bulbasaur is using their Tackle, I roll the d6; on a 1-4, Bulbasaur misses, but on a 5-6, Bulbasaur hits and does 4 damage to their opponent. Some attacks have an added special ability. On the other side of Bulbasaur, for example, their Leech Seed attack does 1 Hit on a roll of 3-6, but in addition, the player gets to flip a coin, and on heads, Bulbasaur can attack with Leech Seed again. Because within the Pokemon universe Bulbasaur has more attacks than Leech Seed and Tackle, you can have multiple Bulbasaur cards, each with different learned attacks. At the time the game was made there was no way to turn your Bulbasaur into an Ivysaur or to teach them more attacks. And since the game was quickly discontinued, we’ll never know what they planned to do in future expansions. I can see why they would want to keep the game simple at first, and grow it in complexity with future products, and the designers clearly left room in the game for that growth. I would love to have seen where they took the game. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed