|

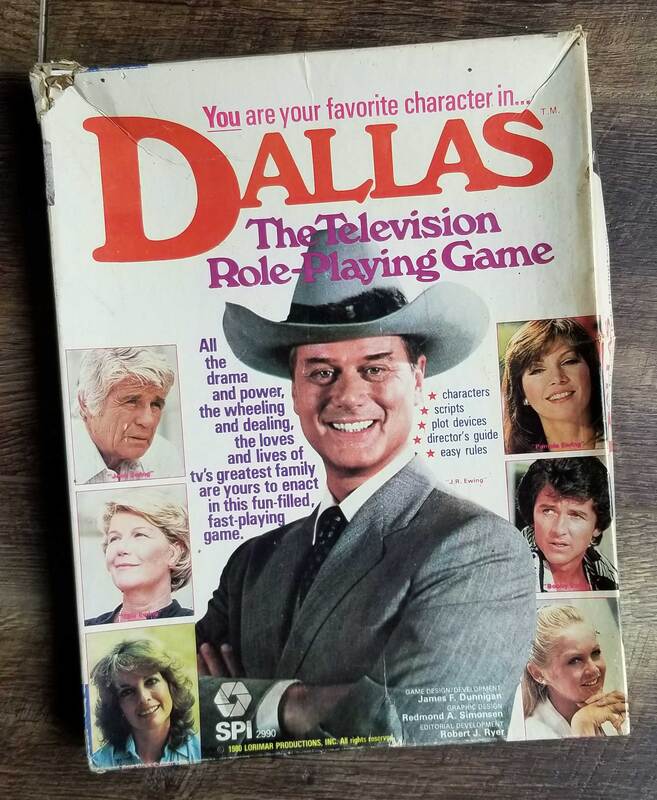

I didn’t know what to expect from Dallas: The Television Role-Playing Game. I had heard some people say that it was more of a board game than a roleplaying game. Others said it had some innovative mechanics and was actually fun to play. Still others just dismissed it as a weird tangent to the hobby, not part of the larger movement of design and play. I found a cheap and battered, but complete, copy on ebay a while back and finally got to read it. I found the design of the game to be surprising and exciting, personally. I was too young to be a fan of the show, so there’s nothing nostalgic in my excitement. I haven’t gotten a chance to play it, and I doubt that I will, but it has given me a lot to think about. First, there are indeed characters you play during the game. The character sheets provide all the relevant stats for 9 major characters of the show. Each character has numbers Power, Persuasion, Coercion, Seduction, Investigation, and Luck. Power and Luck are single numbers representing the character’s ability to exert influence and escape consequences, respectively. The other four stats correspond to the main actions each character can take, and they come with both an offensive and defensive number, measuring their ability to be persuasive, say, and resist persuasion themselves. The character sheets for each character are almost identical, each sheet show all the major characters’ stats on the front of the sheet, and all the rules succinctly stated on the back. The only difference between the sheets is that the character’s specific stats are placed in bold at the top of the sheet, a brief summary of their character and background in the show is given, and the “Personal Victory Conditions” for each of the three scripts included with the game. Let’s talk about those scripts and those “Personal Victory Conditions.” Scripts are equivalent to adventures or modules in other roleplaying games, or variants and situations in board games. Each script gives you a fictional situation for the game, with a specific setup, a list of which major characters are involved, what minor characters and what plot devices will be in play. Each script is like an individual TV episode, with its own beginning, middle, and end. At the start of play, the Director gives a general setup for the fiction of the story. Then, in private, the director gives each player the specific story and goals of their major character. The game then plays out in five or fewer scenes, and at the end, any player who met their personal victory conditions is considered a winner. Personal victory conditions all involve “controlling” a number of assets—those minor characters and plot devices I mentioned earlier. Minor characters, plot devices, and organizational characters (characters with official titles but not individual names—so, an FBI agent, a Texas Railroad Commissioner, and so on) are all printed on individual cards. Plot devices are just names: Ellie’s Letters, Spanish Land Grant, Saddlebag full of Krugerrands, Cowboy-Redskins Football Tickets. These are the MacGuffins characters are fighting over to control. The minor and organization characters come with stats for all the major actions of the game so they can properly assert and resist persuasion, coercion, seduction, and investigation. Some of these cards begin the game on the table face-up, so everyone knows that they are in play; some begin face down, known to some and not to others, driving those players who are not in the know to investigate to find out who these pawns and powers are; and some are brought in by the Director during the game to introduce new developments and tensions. As I indicated, play progresses through scenes. Each scene consists of a number of phases. First, in the Director Phase, the Director gives out information to the group and to individual players, possibly handing out new minor characters or plot devices. This is just an information phase, but that information can easily tilt the landscape of play. The Director also sets up how long the Negotiation Phase, the phase that follows, will be at this time. The Negotiation Phase allows players to talk among themselves and make deals. The players can trade assets (minor characters, organizational characters, and plot devices), form alliances, make plans, and generally agree upon whatever they can. Players are allowed to take other players away from the table in order to make their deals in private. Finally comes the Conflict Phase, in which everyone takes action. You can try to gain control of minor characters by persuading, coercing, or seducing them away from their current allegiance; you can investigate face-down cards to find out what secrets you aren’t in on; you can even attempt to get another major character thrown in jail if it is known that they have committed an illegal act and you have some form or law enforcement under your influence. When the dust settles, the next scene begins with the Director Phase and it starts all over again. At the end of the final scene, you look at what you control and what you need to control to “win” and see how you did. As you can gather from my description, this is a strategic and competitive game. The amount of roleplaying anyone engages in is entirely up to the players involved. It would be easy to play an entire game without once speaking in a character’s voice or building up fictional scenes for your actions. In fact, the one example of play given in the game books shows the players engaging in nothing fictional, focusing entirely on the pieces of play as pieces of play. Nothing in the rules or procedures force roleplaying. But only the focus on achieving your goal might inadvertently stand in your way of actively creating fictional scenes. The rules prohibit the number of actions you can take during the Conflict Phase in order to reflect that what is transpiring is a single scene (or more accurately, I suppose, an act). Your character can only be in one or two places per scene and only affect one character or plot device where they are. So you can easily set up that moment of conflict within the fiction and play it out before rolling the dice to see if you are successful in your act of persuasion or coercion or seduction or investigation. I think it would be quite cool to see that in play. The game immediately put me in mind of Fiasco. Each player has a character driven by their own ambitions and debts, all connected to each other by a web of relationships, fighting over the same limited pool of resources. The plot devices are just “objects” in Fiasco’s language. That Saddlebag full of Krugerrands, for example, could fit into any number of Fiasco playsets. The tone is obviously different, leaning more towards soap than tragicomedy, but the basic idea of play is strikingly similar. Mechanizing the attempts to gain influence over minor characters through persuasion, coercion, and seduction, is a neat idea, and their execution is admirable. Let’s say you are trying to persuade Ralph Bentocher, the senator’s son, to intervene with his father in your interests. You take your offensive persuasion skill (if you’re J.R., that’s 20) and subtract from it your target’s defensive persuasion skill (Ralph, poor soul, only has a 7 to resist), and get a number (in this case, 13). If that number is 0 or 1, you automatically fail. If the number is 12 or higher, you automatically succeed. If that number is between 2 and 11, you roll 2d6 and see if you can roll equal to or less than that number, you succeed. Additionally, your minor characters can work on your behalf, using the same actions, to increase the amount of influence you can exert in any one scene. And you can use your major characters Power score to help give your lackeys a boost in their efforts. So when Ralph talks to his father, the force of J.R.’s name is behind his own roll to persuade. I like it. This is just a side point, but the way the personal victory conditions are described in the various scripts also put me in mind of Fiasco. Here is what J.R. must control at the end of “The Great Claim” script to win: Land Grant The comments give you both flavor and humor, grounding the bits of paper on the table with the fiction of the game. Moreover, it tells you how J.R. thinks and how he manipulates the world. I find their short lists energizing and compelling, making me want to play and engage with the fiction. The game has me thinking about ways to have enjoyable play while major characters have interests pointed directly at each other, where the heart of play is conflict between characters, not in the form or physically battling, but in the form of influence and manipulation. There’s a lot here to feed the mind. If for some reason I was just burning to play a game like a Dallas TV show, I would just create a Fiasco playset, but it would definitely be playing Fiasco in Dallas’s world. There’s one other cool thing I’d like to point to before wrapping up. There is a section in the books that tells you how to create your own character stats, and I think their method is interesting enough to share: In the game, the character Abilities were initially derived through a somewhat abstract process. A character’s Abilities were rendered into six major categories: intelligence, charm, lack of scruples, physical attractiveness, nerve, and power. The ratings were assigned relative to other characters. A 9 is on the high end of the scale, and 1 is the low end, except in the case of power where a character can have zero. Intelligence was evaluated in terms of both intellect and cunning. J.R. was arbitrarily given an 8. In charm, representing the ability to get your own way on the basis of personality, J.R. rated another 8. For lack of scruples, he was assigned another 8 (there are certain things he draws the line at, particularly where his parents are concerned). For nerve, J.R. again rated an 8, as did Pam, Jock, Bobby, and Lucy. For power, J.R. deserved a 9 without question. Two things I want to point to here. The first is that those original stats, the unseen ones, are a perfect breakdown of the descriptors of the characters in the show. To some degree or another, all the characters are intelligent, charming, unscrupulous, attractive, full of nerve, and powerful. To then turn those characteristics into the verbs that are their actions is common enough in roleplaying games, but that step is often left for the players to calculate. You typically determine their stats and use their stats to determine how effective you are at doing a thing. There’s something cool about that happening behind the scenes here. The second thing that I want to draw your attention to is the imbalance of power between characters, which the game embraces without apology. None of the characters have comparable stats. They are not balanced to make sure that Lucy and J.R. have the same chance to do the same things. That’s a bold move, and one RPGs have been wrestling with for a long time. The way Dallas addresses that imbalance is to give each character personal victory conditions in proportion to their character’s ability. Lucy doesn’t need to control nearly as many things as J.R. In fact, some of Lucy’s win-conditions often line up with another character getting what she wants, which means, Lucy can team up with certain characters to each achieve their shared goals. Weaker characters will team up against more powerful characters and alliances will shift as power shifts during the individual games. It’s built to keep play dynamic and interesting.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed