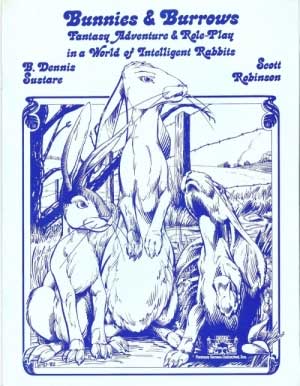

Bunnies & Burrows was published in 1976 by Fantasy Games Unlimited and written by B. Dennis Sustare & Scott Robinson. It is a “Fantasy Adventure and Role Play” game in which the players play rabbits a la Watership Down. But where Watership Down is a drama about a community searching for a home, gameplay in Bunnies & Burrows uses the basic model of hex crawling established by the earliest of RPGs, complete with dungeon-like burrows and caves for the rabbit PCs to explore. As an RPG it is unmistakably a product of its time, but there are a lot of interesting elements to the game. Here’s how the text describes the game and gameplay in the introductory section: “Once the game has been set up by the Gamemaster . . . each player establishes the basic characteristics of their rabbit. . . . The players tell the GM what they want their rabbits to do, moving them about through unknown terrain (and thus finding out what the GM has hidden on the map), interacting with other rabbits they might meet (so called ‘cardboard’ characters, designed and controlled by the GM), and occasionally fleeing from or fighting predators and other enemies of rabbits. The rabbits may fall into traps, locate ‘treasures’ (such as especially good things to eat), be confronted by puzzling situations they must attempt to solve, etc. All the things the rabbits do during these adventures contribute to their experience; in turn, increasing their experience allows them to perform new tasks. You can see from that summary how the game leans heavily on its fantasy RPG predecessors with one-to-one analogs and similar play structures. The whole rulebook is a mere 36 pages, but it packs a lot of rules and information between its covers. The main organizing principle of the rulebook are the 8 “characteristics” that define a player character’s abilities: “There are eight primary characteristics that must be determined for each rabbit; these are Strength, Speed, Smell, Intelligence, Wisdom, Dexterity, Constitution and Charisma. When a player is first starting a rabbit, he rolls three six-sided dice at once, one time for each characteristic, with the sum of the three dice (3-18) giving your innate value for that characteristic. These values will (for the most part) never change during the game” (4). In addition to each characteristic having an innate value, each characteristic has a level: “Each rabbit also has a Level in each characteristic; the Level tells how much experience the rabbit has gained in that area. Every rabbit begins at level 0 in each characteristic” (4) Although there are “professions” for each PC (the equivalent of classes in D&D), rabbits do not level up by profession. There is no such a thing as a 5th level Herbalist, for example. Instead, as the PC performs task that use that characteristic, the player makes a note of it, and at the end of the session, they can roll for a chance to increase the level of that characteristic, although no characteristic can increase more than one level per session. Call of Cthulhu picked up this approach a few years later when it was published, though it implemented the idea differently. Each characteristic is associated with a specific rabbit “profession.” Fighters primarily care about strength, runners primarily care about speed, herbalists primarily care about smell, scouts primarily care about intelligence, Seers primarily care about wisdom, mavericks primarily care about dexterity, empaths primarily care about constitution, and storytellers primarily care about charisma. Since the characteristics, both in their innate score and in their level rank, are the main measure of a PCs effectiveness, the rulebook covers the entirety of what a PC can do in game by going through the characteristics one at a time. Although the game uses d6s during character creation, percentile dice are the main tool for resolving conflict and uncertainty. But other than using percentile dice across the board, there is no standardized resolution mechanic. Instead, each thing a rabbit can do has its own rules for determining a character’s success. So as the rules cover each characteristic, they say what the rabbit can do, how to resolve questions of whether they can do it or how effectively they can do it, and what special advantages the profession associated with that characteristic has. Once the characteristics cover how the PCs can engage with the world, the rulebook turns to how the GM creates the world with which the PCs can then engage. As noted in the first part of this review, play takes the form of a hex crawl. The GM is advised to make out a map and populate it with warrens, caves, traps, predators, and anything else of interest. The players then move their characters through the map and discover what the GM has laid in store. The minute by minute pressures on the PCs take the form of energy and food. By the rules, everything a PC does expends energy, and eating various foods gives the PCs energy when they can then spend. At 0 level, as all rabbits begin, the maximum energy PCs can have is 2. Hopping for an hour uses one energy, sleeping for a night uses one energy, and eating grass uninterrupted for 10 minutes gives you one energy. Moreover, fighting another rabbit takes 5 energy. You can go in debt to do what you need, but negative energy translates into hit point damage, so fights are especially costly for young rabbits. So while exploration is the name of the game over the course of a session, the moment to moment concern is how much energy do you spend and how much energy can you harvest. You can see the bookkeeping that this system mandates. There’s a lot of bookkeeping in general for the GM: “For each rabbit, you must keep a record of innate characteristics, their level in each characteristic, their maximum and current hit points, what languages they know, and what animals they are able to recognize. You must also keep track of what their maximum and current energy level is, how long it has been since they last slept, and what time of day it is. You must know where they are at all times . . . . Due to the poisonweed and encumbrance rules, you must keep track of what they are carrying with them, though this has a tendency to become tedious” (28.) That last line cracks me up, because it sounds like the designers are victim to their own design. That’s not even the first time the designers take that tone. In discussing the saving throws, the text says, “Through years of Gamemastering, we have found that it helps the games for the GM to be flexible in the use of Saving Throws. Rigid adherence to Saving Throw rules tends to be very deadly, with less fun for the players. Accordingly we may shade die rolls just a bit in certain key situations, so that a rabbit may survive to play again” (23). The designers are admitting that the rules they created don’t quite work the way they want them to in every situation, so they lean on the GM to “shade” things to make them work alright in spite of the rules. I realize that this was not an uncommon problem or solution in the early days of the hobby (and in fact can still be seen in some games being published today), but all that says to me is that they got tired of working with the system to make it right, so here, fix it for us in play. Curiously, along the same lines of the designer trusting the GM to compensates for faulty design, the thing that the designers love most about play is left to the players to create through emergent play without help from any game mechanics: “In our play of the game, the player rabbits started out with few distinctions except for their names and basic characteristics. . . . As the game progressed, chance events tended to endow our rabbits with personalities of their own. One rabbit might have been lucky the first few times he disabled traps, and acquired a tendency to be reckless, trusting in his luck. Another might have been badly damaged in a fight and decide to do anything possible to avoid fighting again. Two rabbits might acquire a habit of daring each other to do wilder and wilder things. All ways in which rabbits are made more distinctive adds considerable interest to the game, and should be heartily encouraged. Once your rabbit acquires some traits, you should try to keep his behavior in character during future play, even when it is not in your best interest to do so! Believe it or not, this makes the game more fun in the long run. The development of individual personalities of the rabbits and the development of the cultural and physical world are the real magic of play, according to this insightful passage by the designers. How high you can jump, how much you can carry, how the GM has laid out her map—none of those things build your personality of create legends & beloved NPCs. I love that the designers are able to point to exactly where the magic of play lies, and I understand why they didn’t see any problem with the fact that none of their systems are designed to bring those moments of magic into existence, but, man, imagine how great a game they could have created if they designed specifically toward that experience. There is actually one rule that actively contributes to this world building that the designers love. To learn a new language, the rules dictate that you need to find a speaker of that language and, determined by your instructor’s intelligence, you need to spend some number of hours studying with your teacher at no more than one hour a day. So if you want to learn the language of pics, say, you need to have a relationship with a pig willing to teach you, and you need to spend a lot of time with this teacher. Those fictional demands make fertile ground for the kind of fun the game wants to produce. Seeing what the designers want the game to do makes sense of a statement in the text’s introduction that originally had me scratching my head: “[T]here is a Gamemaster (GM) that oversees the game, designs the playing area, is expected to modify the rules given herein to suit his or her fancy, and is the only omniscient participant in the game. Indeed, much of the fun for the players lies in not knowing all of the rules, but having to deduce the rules of the game as the game progresses” (4) Why wouldn’t you want players to know the rules of the game?! Now, I think it has less to do with worrying that the players will know which herbs can do what and more about having the players focus on the fiction of the game rather than the mechanics, because the magic is in the fiction, not in the rules of play. The designers don’t want players worrying about how well they can do something; they just want them to make their characters act and react as the fiction carries them along.

0 Comments

Review of WeG's 1986 Ghostbusters RPG (Because I have my fingers on the pulse of the RPG industry)3/10/2019 Ghostbusters is one of the seminal roleplaying games of the 1980s, popular and influential, so I decided it was time to give it a read and a study. The game fancies itself as a rules-light game, with a minimalist structure—just enough to function well and smoothly, with as few rules as possible: “And when we started out with the objective of creating a roleplaying game with a one-page rule book, we knew it was an impossible and Quixotic quest. Nonetheless we were pleasantly surprised at how much we could get out of a fairly simple system. Sure, we knew from our success with PARANOIA that folks wanted a freewheeling, improvisational structure to do some Real Roleplaying, but we also knew that Numbers, Rules, and Dice-Bouncing are fun, and we were hoping to get the best of that world without the vexatious burden of Charts and Tables, Section 4.3.13, and The Wonderful and Exciting World of Bookkeeping” (Operations Manual, p 3).  The main element that streamlines the game’s rules is that characters and creatures don’t have any kind of hit points, which means that combat is simplified, the weapons list is simplified, and there is no need for a “monster manual” of any kind. All of that exists as a mere matter of fiction and fall under the providence of the GM (known as the “ghostmaster” in the game). The other main tool to streamline the rules is to put a lot of power in the GM’s hands, both in making decisions about how things work and in creating fiction to steer play, as you’ll see throughout this review. Characters meanwhile are defined by four “traits”: brains, moves, muscle, and cool. Players are given 12 points to divide among the four traits, giving each a minimum of one and a maximum of five. Within each trait, the player can designate a “talent” that the character is especially good at. Talent lists for each trait are provided for players to choose from, although they can make up their own at the GM’s approval. The rank of each talent is three more than the trait with which it is associated, so a character might have 3 brains and 6 puzzle solving. Talents are a neat trick at giving characters particular strengths while keeping the overall number of traits low. Moreover, character’s particular interests and characteristics come into focus through that list of traits. Two characters can easily enough end p with the same or similar trait points spread, but their talents can vary widely. This feature is especially prevalent in the stats for NPCs. For example, a “libidinous doctor” in the cast of characters section at the back of the Operations Manual has these stats: Brains 3 Use Influence 6 The talents go a long way to bringing a character to life in your head through a few deftly worded phrases. A mere glance at the talents lets you know how to play this character. The examples of talents in the game call on tropes and stereotypes, which haven’t aged well, over all, but the technology is still excellent. Jonathan Tweet used it in Everway, Robin D. Laws uses a similar technique in Hero Wars, and many other games have picked it up as well. The rank for each trait and talent are indicative of the number of d6s rolled in any test involving them. For any challenging action, the GM determines a target number (the general guidelines given in the text are 5 for easy tasks, 10 for normal tasks, 15 for hard tasks, and 20 and up for nearly impossible tasks). The player rolls the dice in their character’s trait pool, and if they meet or exceed the target number, they are successful. If two characters are competing against each other or are in a direct fight, they roll their relevant traits and the highest roll wins. Pretty simple. And pretty unexciting. To make it more exciting, the designers created the “ghost die,” a regular d6 with a ghost symbol where the number 6 should be. Whenever a player rolls dice, one of them (and only one of them) must be the ghost die. Whenever a ghost is rolled, the die’s value is zero, and the GM has permission to make a troublesome (and humorous) outcome, even if the dice pool roll overall is a success. It’s a simple and exciting way to throw uncertainty into die rolls beyond the question of success and failure. The ghost die is particularly suitable to the tone of the game, which is comical and even cartoonish at times, so the ghost die gives everyone at the table permission to be especially silly in their narrative descriptions. The other major mechanical element of the game are “brownie points,” which take the place of experience points, hit points, and other character resources. Characters begin play with 20 brownie points. At the end of any scenario, the GM decides how many brownie points to reward: half as many as they spent if the characters did not accomplish the goals of the scenario, as many as they spent if they achieved the goal only, and one and a half as many as they spent if they did an especially good job. In addition, each character has one of five personal goals (sex, soulless science, fame, serving humanity, and wealth), and if they take actions to meet those personal goals, they can get additional brownie points. If at any time a character is desperate for brownie points, the player can reduce one of the character’s trait permanently by one rank to give that character 20 brownie points. Brownie points can be spent in a number of ways. Before a player rolls for their character to accomplish a task, they can spend brownie points on a one-for-one basis to get extra dice for that one roll. If a character has the points, they can spend 30 points to permanently raise a trait by one rank. Brownie points are also spent to avoid personal injury or fallout from a poorly done action. When a character faces a tough fate or physical danger, the GM can charge the character brownie points to avoid death or permanent injury. Is your character falling from a rooftop because of a bad roll, mark off 5 brownie points and describe how you comically make it to the ground safely. Players are encouraged to be as comic and entertaining as possible as the rules permit the GM to return brownie points for especially entertaining narrations. While characters can eventually increase their traits, the game doesn’t envision that as the main point of growth and change. Change occurs primarily through the fiction, as the GM is encouraged to make NPC return in subsequent adventures and to make PC decisions have lasting consequences within the fiction. The franchise’s rocky relationship with the EPA and other government regulatory bodies as well as the fiscal dangers of running a franchise. The franchises are central to campaign play, and they exist entirely within the fiction (by which I mean there is no mechanical aspect to them, no stats, traits, or numbers of any kind). Similarly, when the books offer solutions to broken play, those solutions are themselves anchored in the fiction. For example, if the PCs develop a piece of scientific equipment that allows the characters to shortcut the drama of play in future adventures, the text suggests using “Crusader Koalas from Beyond Space and Time”: “The stubby little marsupial says, in a deep and resonant voice, ‘This device threatens the very fabric of the universe. Your race is not sufficiently wise to use it well. I must excise all knowledge of it from your mind and return you to your proper time and place” (Operations Manual, p. 60-61). There is a whole set of fictional solutions to players trying to out-clever gameplay. The rulebook is a fun read as the tone matches the intended tone for the game. That said, the particular source of a lot of the humor is cringeworthy and painful, as it is clear that the text was written in the 1980s by a set of white men. The GM is repeatedly advised to play up characters’ accents for humor. Every woman is a target for the PCs, especially characters with the personal goal of “sex,” who are trying to get a date with anyone to get the extra brownie points at the session’s end. Yes, characters roll their moves trait to score a date, and the difficulty of the target number is supposed to increase with the hotness of the woman they are targeting. These are not a couple of misstatements in the texts, but a whole and consistent focus on things that should not be the source of humor. The boxed set gives players a lot of tools to play the game, including 3 scenarios and 21 scenario seeds. There are dozens of pre-created NPCs that can be pulled out when needed (and yes, that’s plenty more uncomfortable tropes and characterizations, so prepare yourself). It’s a thoughtful (when the content itself is not thoughtless) set of tools designed to bring new roleplayers into the hobby, quickly getting them running and creating their own scenarios.  I’ve recently decided to support Bully Pulpit’s Drip project. Their most recent game released to Drip supporters is a “semi-larp, structured freeform” game called “Deep Love.” The game is now available on DriveThru at https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/266580/Deep-Love?term=deep+love. I haven’t played in any larps and have read only a few larp texts, so this is something new for me, but after reading “Deep Love,” I’m excited to read more. The game is designed for exactly four participants. Here’s the setup: In Deep Love you’ll play the four principals in the 1934 New York Zoological Society/National Geographic Society expedition to explore the deep waters off Bermuda, descending far deeper than anyone in history. The four characters form a complicated web of love, loyalty, and affection, and amid the stress and excitement of the four dives in the bathysphere you will sort out your feelings for one another and – hopefully – leave the expedition happier than you arrived. You need two spaces to play the game, one to represent the deck of the Ready, the ship carrying the bathysphere, and a cramped space (a closet or bathtub is recommended) to represent the bathysphere itself. Play consists of four 20-minute dives of two players in the bathysphere with the remaining players on the Ready, with five-minutes scenes back on deck between dives. During the dives, players in each space communicate with the players in the other space via walkie talkies or cell phone for two specific reasons: 1) to give instrument readings in the bathysphere, which are recorded in a logbook by the players on deck, and 2) to describe the mysterious underwater sea life they are witnessing, which the players on deck are encouraged to draw. Here’s what the rules say about the sketches: Of course it is hard to separate their friends and lovers from the wonderful animals they are describing from so far away. They should keep the divers in mind as they sketch – perhaps each fish is less scientific illustration and more emotional metaphor, or even a representation of that diver from the point of view of the sketcher! Great art is not the goal, but rather a sense of intimacy and perhaps wonder. Like so many of Jason Morningstar’s games, “Deep Love” is anchored in a specific setting and a specific timeframe that requires a lot of knowledge from the players in order to bring those things to life. Thankfully, one of Jason Morningstar’s many talents is providing such information deftly and succinctly in a way that doesn’t place much cognitive load on the players. Each player gets a sheet that summarizes who your character is and what your relationships with each of the other characters are. On the back of that character sheet is a unique list of descriptors for describing the imagined underwater sea life that they see out the bathysphere. The player just grabs a few descriptors from each category to describe some fantastic underwater creature. In addition, the game comes with a set of checklists for each dive so that the players understand the physical demands and dangers of the diving machinery. And not only is there a logbook for recording all the instrumental readings from the bathysphere, there is a set of graphics for the six instruments at various underwater depths, tracking oxygen, sea temp, sea pressure, as well as humidity and temperature and pressure in the cabin. The players on the deck have a list that tells correlates the time into the dive with the depth the bathysphere should be at, so they can report the depth and ask the divers to report the instrument readings. It’s all such a clever way to create the “realistic” details needed to bring the setting to life without requiring the players to know anything about diving, 1934, or these people when play begins.

What strikes me most about the game as I imagine it being played is the gentle mix of freeform conversation and required tasks. Characters have motivation to talk to each other, to discuss their relationship and their friends and to figure out what they want from both. At the same time, there is stuff for the players to be doing while they talk. Not only can the activities provide refuge for the players if they need a moment to think or process, but the activities shape the conversation and constantly provide new input and circumstances. In any 20-minute dive, the players in the two spaces will talk to each other eight separate times: four times to discuss instrument readings, and four times (twice for each diver) to describe the sea life out the window. On average then, each pair needs to interrupt their conversation every 2.5 minutes to converse with the other pair. And you don’t know when that interruption is going to come, which makes the conversation that much more charged and potentially fraught. And of course, if you want to break the conversation you’re currently in, you can instigate the next call to the other team. It’s organic and simple and beautiful. It’s what screenwriters do all the time, putting conversations in the context of activities so that each interrupts and colors the other. Complicating matters more, and putting in a bit of the uncontrollable, there is a deck of eight “Trouble” cards. At some point during the dive, the diving players draw a card from the Trouble Deck to symbolize some complication that occurs at that time. Nothing is life-threatening, so players don’t need to worry about dying in the depths, but each one can affect the conversation and the length of the dive. Cables can break, sending the bathysphere spinning; electrical failure can occur, leaving the divers in utter darkness except for the bioluminescent life out the window; communication can fail between the bathysphere and the Ready. It’s a neat little jolt that affects play without disrupting it. The other thing I love about this game is the nature of everyone’s relationships. Everyone here loves and likes everyone else. And while everyone is sorting out their feelings, they’re concerned for everyone else’s feelings. The result is a dramatic but loving game. This will not produce a Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf story (though I’d love to see that game too!). You want to play the game after reading the text in order to know how the events and relationships could play out. The game sets up an interesting situation with interesting dynamics, and no matter what happens, it’s bound to be a neat tale. I would like to see this movie, and I would like to play this game. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed