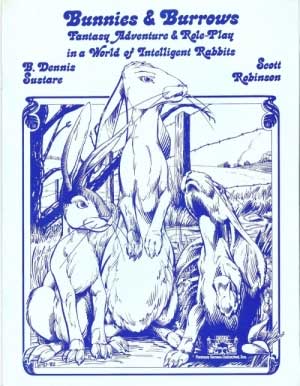

Bunnies & Burrows was published in 1976 by Fantasy Games Unlimited and written by B. Dennis Sustare & Scott Robinson. It is a “Fantasy Adventure and Role Play” game in which the players play rabbits a la Watership Down. But where Watership Down is a drama about a community searching for a home, gameplay in Bunnies & Burrows uses the basic model of hex crawling established by the earliest of RPGs, complete with dungeon-like burrows and caves for the rabbit PCs to explore. As an RPG it is unmistakably a product of its time, but there are a lot of interesting elements to the game. Here’s how the text describes the game and gameplay in the introductory section: “Once the game has been set up by the Gamemaster . . . each player establishes the basic characteristics of their rabbit. . . . The players tell the GM what they want their rabbits to do, moving them about through unknown terrain (and thus finding out what the GM has hidden on the map), interacting with other rabbits they might meet (so called ‘cardboard’ characters, designed and controlled by the GM), and occasionally fleeing from or fighting predators and other enemies of rabbits. The rabbits may fall into traps, locate ‘treasures’ (such as especially good things to eat), be confronted by puzzling situations they must attempt to solve, etc. All the things the rabbits do during these adventures contribute to their experience; in turn, increasing their experience allows them to perform new tasks. You can see from that summary how the game leans heavily on its fantasy RPG predecessors with one-to-one analogs and similar play structures. The whole rulebook is a mere 36 pages, but it packs a lot of rules and information between its covers. The main organizing principle of the rulebook are the 8 “characteristics” that define a player character’s abilities: “There are eight primary characteristics that must be determined for each rabbit; these are Strength, Speed, Smell, Intelligence, Wisdom, Dexterity, Constitution and Charisma. When a player is first starting a rabbit, he rolls three six-sided dice at once, one time for each characteristic, with the sum of the three dice (3-18) giving your innate value for that characteristic. These values will (for the most part) never change during the game” (4). In addition to each characteristic having an innate value, each characteristic has a level: “Each rabbit also has a Level in each characteristic; the Level tells how much experience the rabbit has gained in that area. Every rabbit begins at level 0 in each characteristic” (4) Although there are “professions” for each PC (the equivalent of classes in D&D), rabbits do not level up by profession. There is no such a thing as a 5th level Herbalist, for example. Instead, as the PC performs task that use that characteristic, the player makes a note of it, and at the end of the session, they can roll for a chance to increase the level of that characteristic, although no characteristic can increase more than one level per session. Call of Cthulhu picked up this approach a few years later when it was published, though it implemented the idea differently. Each characteristic is associated with a specific rabbit “profession.” Fighters primarily care about strength, runners primarily care about speed, herbalists primarily care about smell, scouts primarily care about intelligence, Seers primarily care about wisdom, mavericks primarily care about dexterity, empaths primarily care about constitution, and storytellers primarily care about charisma. Since the characteristics, both in their innate score and in their level rank, are the main measure of a PCs effectiveness, the rulebook covers the entirety of what a PC can do in game by going through the characteristics one at a time. Although the game uses d6s during character creation, percentile dice are the main tool for resolving conflict and uncertainty. But other than using percentile dice across the board, there is no standardized resolution mechanic. Instead, each thing a rabbit can do has its own rules for determining a character’s success. So as the rules cover each characteristic, they say what the rabbit can do, how to resolve questions of whether they can do it or how effectively they can do it, and what special advantages the profession associated with that characteristic has. Once the characteristics cover how the PCs can engage with the world, the rulebook turns to how the GM creates the world with which the PCs can then engage. As noted in the first part of this review, play takes the form of a hex crawl. The GM is advised to make out a map and populate it with warrens, caves, traps, predators, and anything else of interest. The players then move their characters through the map and discover what the GM has laid in store. The minute by minute pressures on the PCs take the form of energy and food. By the rules, everything a PC does expends energy, and eating various foods gives the PCs energy when they can then spend. At 0 level, as all rabbits begin, the maximum energy PCs can have is 2. Hopping for an hour uses one energy, sleeping for a night uses one energy, and eating grass uninterrupted for 10 minutes gives you one energy. Moreover, fighting another rabbit takes 5 energy. You can go in debt to do what you need, but negative energy translates into hit point damage, so fights are especially costly for young rabbits. So while exploration is the name of the game over the course of a session, the moment to moment concern is how much energy do you spend and how much energy can you harvest. You can see the bookkeeping that this system mandates. There’s a lot of bookkeeping in general for the GM: “For each rabbit, you must keep a record of innate characteristics, their level in each characteristic, their maximum and current hit points, what languages they know, and what animals they are able to recognize. You must also keep track of what their maximum and current energy level is, how long it has been since they last slept, and what time of day it is. You must know where they are at all times . . . . Due to the poisonweed and encumbrance rules, you must keep track of what they are carrying with them, though this has a tendency to become tedious” (28.) That last line cracks me up, because it sounds like the designers are victim to their own design. That’s not even the first time the designers take that tone. In discussing the saving throws, the text says, “Through years of Gamemastering, we have found that it helps the games for the GM to be flexible in the use of Saving Throws. Rigid adherence to Saving Throw rules tends to be very deadly, with less fun for the players. Accordingly we may shade die rolls just a bit in certain key situations, so that a rabbit may survive to play again” (23). The designers are admitting that the rules they created don’t quite work the way they want them to in every situation, so they lean on the GM to “shade” things to make them work alright in spite of the rules. I realize that this was not an uncommon problem or solution in the early days of the hobby (and in fact can still be seen in some games being published today), but all that says to me is that they got tired of working with the system to make it right, so here, fix it for us in play. Curiously, along the same lines of the designer trusting the GM to compensates for faulty design, the thing that the designers love most about play is left to the players to create through emergent play without help from any game mechanics: “In our play of the game, the player rabbits started out with few distinctions except for their names and basic characteristics. . . . As the game progressed, chance events tended to endow our rabbits with personalities of their own. One rabbit might have been lucky the first few times he disabled traps, and acquired a tendency to be reckless, trusting in his luck. Another might have been badly damaged in a fight and decide to do anything possible to avoid fighting again. Two rabbits might acquire a habit of daring each other to do wilder and wilder things. All ways in which rabbits are made more distinctive adds considerable interest to the game, and should be heartily encouraged. Once your rabbit acquires some traits, you should try to keep his behavior in character during future play, even when it is not in your best interest to do so! Believe it or not, this makes the game more fun in the long run. The development of individual personalities of the rabbits and the development of the cultural and physical world are the real magic of play, according to this insightful passage by the designers. How high you can jump, how much you can carry, how the GM has laid out her map—none of those things build your personality of create legends & beloved NPCs. I love that the designers are able to point to exactly where the magic of play lies, and I understand why they didn’t see any problem with the fact that none of their systems are designed to bring those moments of magic into existence, but, man, imagine how great a game they could have created if they designed specifically toward that experience. There is actually one rule that actively contributes to this world building that the designers love. To learn a new language, the rules dictate that you need to find a speaker of that language and, determined by your instructor’s intelligence, you need to spend some number of hours studying with your teacher at no more than one hour a day. So if you want to learn the language of pics, say, you need to have a relationship with a pig willing to teach you, and you need to spend a lot of time with this teacher. Those fictional demands make fertile ground for the kind of fun the game wants to produce. Seeing what the designers want the game to do makes sense of a statement in the text’s introduction that originally had me scratching my head: “[T]here is a Gamemaster (GM) that oversees the game, designs the playing area, is expected to modify the rules given herein to suit his or her fancy, and is the only omniscient participant in the game. Indeed, much of the fun for the players lies in not knowing all of the rules, but having to deduce the rules of the game as the game progresses” (4) Why wouldn’t you want players to know the rules of the game?! Now, I think it has less to do with worrying that the players will know which herbs can do what and more about having the players focus on the fiction of the game rather than the mechanics, because the magic is in the fiction, not in the rules of play. The designers don’t want players worrying about how well they can do something; they just want them to make their characters act and react as the fiction carries them along.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed