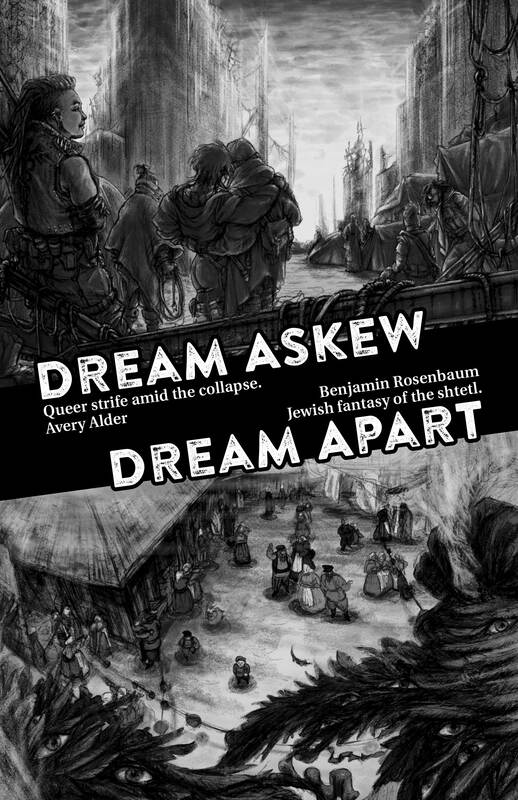

I’m looking today at the 2018 publication of Avery Alder’s Dream Askew and Benjamin Rosenbaum’s Dream Apart. This is a look at the text and mechanics, not a review or play report. In fact, I have not played either game, so take that for what it’s worth. The two games in the collection are presented at “two points [that] make a line” (161)., and the book devotes a chapter at the end of the book to creating your own game using the same system. The uniting similarity in the subject matter of these games are that they create stories “about marginalized groups establishing an independent community just outside the boundaries of a dominant culture” (161). Alder’s poetic name for this type of story is “belonging outside belonging.” In Dream Askew, players play characters in a post-apocalyptic quee community that exists on the edges of “the society intact.” In Dream Apart, players play members of a fantastical 19th-century Eastern European shtetl. Dream Askew was originally a hack of the Bakers’s Apocalypse World, and it still wears that heritage on its sleeve, or, its playbooks. But the belonging outside of belonging system is markedly different from the other games powered by the Apocalypse. First, there is no GM or MC (or there are many GMs and MCs if you prefer to look at it that way), and second, there are no dice. Alder calls the system, for obvious reasons, “no dice, no masters.” Replacing the dice is a simple token economy. On each playbook characters have a list of strong, regular, and weak moves. Any time a character makes a weak move, the player gets a token, and any time the character makes a strong move, the player must spend a token. Regular moves neither gain nor require tokens. Weak moves “show us your character’s vulnerability, folly, or even just plain rotten luck,” and strong moves “are the moments when your character’s skill, power, astute planning, and good luck come to bear and transform a situation” (31). Weak moves “illuminate how the character role copes with stress, fear, and scarcity,” while strong moves “showcase how a character claims power, what instincts they have well-honed, and what value they bring to their community” (166). Each character also has a “lure,” which encourages other players to have their characters interact with your character in a specific way. For example, the stitcher’s lure says, “whenever someone comes to you with something precious that needs fixing, they gain a token.” All lures reward players with tokens. In lieu of an MC, these games each provide six “setting elements,” which tell the players what aspects of the world are important to each game. The setting elements are picked up and put down as needed, with each player being responsible for only one element at a time. The elements are a neat design. Whenever an element is picked up for the first time, including at the start of play, the player who picks it up marks two “desires” from a pick list, which defines the specific nature of that element in this particular game we’re playing. For example, the pick list of desires for the setting element “Outlying Gangs” in Dream Askew is this: “territory, unspoken fealty, splendor, the smell of fear, home-cooked meals, mutant blood, somewhere safe to sleep.” So every time you play Dream Askew, there will be outlying gangs at play, but the nature of those gangs will shift each game as one player characterizes them with two items taken from the list. It’s a great way to define the element and tonal range of that element while at the same time allowing room for taste and, of course, replayability. Setting element playsheets also have a short list of moves to help players figure out how to have the setting express itself in the fiction. There are a ton of things to turn over and analyze here, but I want to jump to what is most surprising to me. The up-to-now standard way of doing things in GMless/GMful games is that the system must take over some of the duties that have traditionally belonged to the GM, such as spotlight control and scene construction authority. Many games have relied on turn taking to ensure that each character gets an equal number of scenes and to designate who is responsible to setting each scene. No such system exists when you’re “playing the dream.” Players are encouraged to begin play by “idle dreaming’: This is the time for questions and curiosity, for tangents and musings. Talk about whatever is interesting, or unknown, or scary, or beautiful about this place that you’re building together. Make up details about the landscape, its history, and its residents. Setup becomes play, one flowing directly into the next (24) Eventually the process of ideal dreaming results in the players finding a scene they want to play out or an area of the world they want to explore through play. The players work out for themselves which scene they will play and where it will begin. There are no mechanics in place for who speaks when to establish what in the fiction. The expected (and required) negotiations rely on players being generous with each other and fans of the other characters, which is what many elements of the design are made to do, create that space of shared kindness, respect, and curiosity. In addition to have no system for scene creation, there is no system for who talks when as the scene unfolds. If your character is in a scene you can make their moves. If the setting element you hold is relevant, you can make setting moves, and if the setting element you hold is not relevant, you can look at the unused setting elements to see if they are and pick them up instead. In addition, players can ask questions and throw out suggests at any time. The character playbooks and setting elements are about what to say, not when to say it. Even Archipelago III has a more defined system for when and what players can say through its ritual phrases. The complete lack of rules governing the conversation is shocking to me because it is so unusual. But it makes perfect sense for telling this kind of story, right? The world of Dream Askew has the possibility of being anarchic (in the political sense) and that is, I’d argue, the ideal state of things, where there is no power structure but equality and the rules that govern are those of respect, kindness, and love. Alder’s system works to create that at the table, or at least create the space for that to happen at the table. Alder makes sure there are safety tools in place, allowing players to pause play to deal with problematic content, encouraging players to ask questions so that they understand game concepts or concepts in the fiction that are unclear to them, and permitting players to gently correct each other to share subject information during play. In addition to these tools, each game comes with a recipe related to the game so that players can eat together and connect as a group of human beings before playing the game. For the game to work smoothly and safely, players much have the means to feel safe, comfortable, and united to some degree. Even removing the dice is to an extent a safety tool. Your character can only enter into trouble and hard times as you dictate them. You say when they are weak and you say when they are strong. It’s a cool design. The vulnerability of the design is of course the same vulnerability of anarchic societies. They are vulnerable to strong personalities taking control. They are vulnerable to a group of timid players tiptoeing around scenes, not wanting to mess things up or get things too dirty. Every game system is of course vulnerable to players; that’s part of the thrill of our hobby. Players are always what makes the game fantastic or disappointing, and a system needs to support players to be at their best and make it difficult for them to be at their worst even if it can’t stop them. There is a vast amount of trust in Alder’s design, and it puts that trust in its players and attempts to build that trust between its players, and then it relies on that trust to make the game the experience everyone wants it to be. My guess is experience with the system will vary widely, both between groups and between individuals. For some, it will be everything they have been looking for in an RPG; for others it won’t provide the gas and random inputs they want to create stories that threaten to run out of their control. But that’s a good place for a game to be, or any piece of art. Those who love the work will find it and be thankful it’s there. Those who don’t have plenty of other places to turn to.

5 Comments

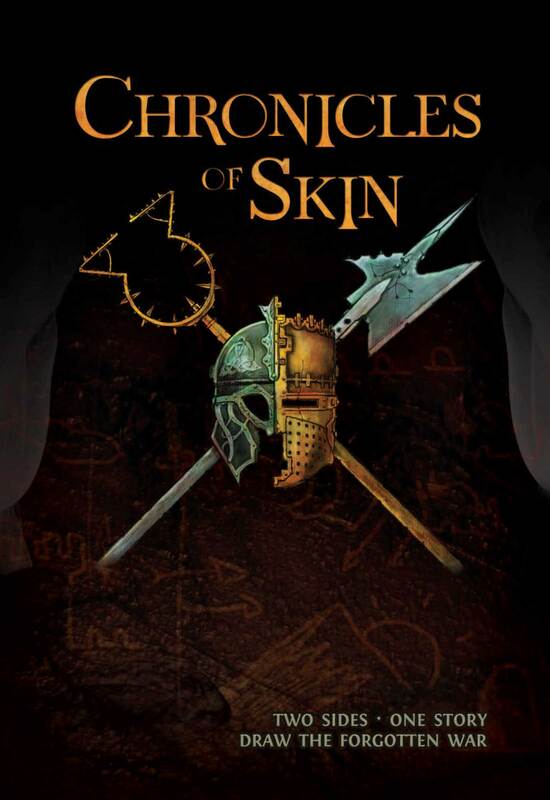

Cat is the third John Wick game that I have read, and like all of his other books, this one is an enjoyable read. Wick exceeds at creating clever worlds with strong interior logic and humor. Cat reminds me of Orkworld in that the big lure of the game to me is less in its mechanical workings and more in its fictional setup. Cat is about “cats who protect their owners from monsters they can’t see.” Players play cats in our real world whose owners suffer from the insidious attacks of Boggins. Boggins are invisible to human eyes, and in the game, they are the physical representations of the troubles we experience—self doubt, depression, guilt, worry, etc. In putting together the world, Wick makes sense of the odd and funny behavior of cats and dogs and humans. It is a lovingly created game and a love song to the cats in our lives and our special relationships with them. The mechanics of the game are simple and functional. Characters have a set of stats that cover the various actions cats might do in any given session. Cats have special traits called “reputations” that help them do those tasks. Between their trait dice and their reputation dice and any advantage dice they might pick up from narrative positioning or GM good will, the player puts together a pool of dice to see if their cat succeeds at their risky task. Evens rolled designate a success; odds denote a failure. The player counts up their number of successes and see if they meet the number needed. Worse comes to worst, players can use one of their cats starting nine lives to guarantee an automatic success. There are rules for fighting, suffering wounds, and healing. There is a subsystem for magic and a set of 8 tricks (cats perform tricks with magic, not cast spells) that can do things like make you always land on your feet or magically slip through a closed door. The rules are simple, designed to allow for improvisational play by both the players and the GM (whose roll is called “the narrator”). The game text comes with several starting situations with the idea that little other preparation is required to move into play. Everything else, then, just needs to be functional and easily applied to make play as smooth as possible. Players are here to be cats, not to marvel at the mechanics of the game. That said, there is one mechanism that I find clever. Cats get scars as their form of injury. The way you determine your scars is this. After you roll, if you don’t have enough evens (successes) to overcome your task, and if the failure risks injury in one form or another, then you look at your dice pool and find the lowest odd number that you rolled. That number is the number of scars that you take. This little device seems to be the reason to use even and odds (rather than, say, the more common 4 and up versus 3 and under). I have never seen that done before, and it makes the system of odds and evens worth it. If you roll a large pool & you surprisingly fail, you’re likely to have a low odd so the scars are minimal. When you only roll a few dice, the chances for large scars is more subject to the swing and luck of the dice.  I don’t know who or what directed me to Sebastian Hickey’s 2012 storytelling/map game Chronicles of Skin. The rules of the game are available for free download at DriveThru, but the game is played with cards, and those cards are not available there. So far as I know, the game is no longer in print, and the only place I know of to get a full copy of the game is on an Italian website, but I’m assured that the cards are in the original English. If you’re looking for them (and/or a download of the Skin sheet), you can find them here: http://www.coyote-press.it/shop/skin/. The game itself guides the players in telling the forgotten history of a great civil war between two cultures who were once united under a single leader. In the first scene of play, that leader dies, and the schism begins. Play then covers two or three additional pivotal moments from the war before it is discovered who won the war and what legacy the victors have left. The central element of play is called the “skin”—this is a single page that holds the information about the two cultures at war and the 3 or 4 important locations in the realm. Players draw on the map (I call it a map, but it’s less a geographic in nature than abstract in its representation), creating pictorial representations of the character of each of the cultures and the locations of their story. As play progresses, the important events of each locations are added to the map, along with representations of the numbers who tragically fell there. At the end of play, the skin becomes an artifact of play, a complete pictorial representation of the story that unfolded in play. To make understanding the game as easy as possible, the rules include two versions of the game. The Chronical version allows players to have complete artistic control over all the elements of play. The Sketch version gives players the basic elements of the cultures and locations at the outset of play. Play itself is also more structured in the Sketch version in order to introduce players to the unusual mechanics in the game. The main mechanics during scenes come into play not when you way what the character you are playing does, but when you attempt to make another player’s character take action. This simpler version is also a quick version, making the play experience a 90-minute game rather than a 4-hour game. Unlike most basic versions that appear in RPGs, the Sketch version looks exciting to play even for experienced players. (I say “looks” because I have not been able to play the game yet, though a friend was kind enough to sell me his physical copy when I made inquiries!) I could see playing this version as a way to play quickly with new or experienced players and still have a great time. I would not feel the need to skip this version to get to the good stuff, which says a lot about the way the game is constructed. The two cultures are always called the Croen and the Iho. In Chronicle play, the players use a set of rune cards to decide the nature of each culture by deciding the following things: each culture has an “aspect,” or some defining trait; a “belief,” a superstition or prophecy that’s important to the culture; and a “rule,” a privilege or crime that dictates conduct. Once these three traits have been decided for both the Croen and the Iho, another card is used to determine the “unity,” an important person or mythological figure that is central to both cultures. The rune cards each have four images, one for each of the four categories (aspect, belief, rule, and unity)—e.g. an anchor, a crown, a spider, a flame—and the players use that symbol as inspiration for whatever trait they are determining. The rune cards are a neat prompt that gives players something tangible to bounce off when creating a trait. Moreover, any single player is responsible for one small decision so the risk of creative paralysis is minimalized, and the resulting culture is both unique and something that everyone had a hand in. The game is built around this idea of giving the players a handhold and then asking them to create something small to add to it. The locations, for example all have names: Chikugo, Seraphim, Cross, and Byzen. The players can then build off these names to create the places that they would like to see in the story. So if you want a battle on open farmland, you might create the Byzen Plains. Another might create the Chikugo Coast, or the Gates of Seraphim, or the Cross on the hill. Players can look at the traits for the Croen and Iho that they have already created as further inspiration, so if the Iho are said to be fire-eating enchanters, a player might be inspired to create Mount Seraphim, an active volcano and a holy mecca to the Iho. First the game gives you something, then you build on it, then it gives you something more, and you have that and everything that came before to build from. Things grow organically and creativity leads to more creativity. Play itself takes the form of a scene at each location on the map. Players take turns being the “scribe.” The scribe has certain responsibilities that a GM might have in a traditional RPG. The scribe sets the scene and decides which of the two cultures that scene will be about. Then, once the scene is set, each player flips over a character card, and the character card tells them a bit about the character and leaves the player to fill in the detail. The card gives you a name, a general rank (meaning high rank, medium rank, or low rank) in the social order, and then names a specific cultural trait and notes whether that character embodies (or benefits from) that trait or rejects (or is negatively affected by) that trait. For example, a player might flip over Babyss, a low ranking Iho who supports, embodies, or benefits by the Iho aspect. That gives you a lot of information to piece together a character who would belong in the scene the scribe has set. You know who they are, where they stand in the power structure (especially in relation to the other characters), and you know what they believe in and embrace or what they reject and fight against. The rules for play are stricter in the Sketch version than in the Chronicle Version, but in both versions players take their primary actions by either choosing to “puppet” another character or by introducing an “event” that happens within the scene that then requires another character to be “puppetted” in response. To “puppet” is merely to tell another player what you want their character to do. The player can either accept this action or reject it. If the action is accepted, it happens. If rejected, there is a resolution mechanic that decides if the action happens or not. All of this means that characters are handled very differently than traditional RPG systems. First, players play 3 or 4 characters in the course of the game, and they manipulate other players’ characters. It’s a clever way to make sure that everyone is invested in what every character says and does without letting players step on each other’s toes in gameplay. The secret to making this work is to have a functional system of negotiating between players. First, because players are always playing different characters, they have no reason to be overly invested in the actions of this particular characters, so agreeing to another player’s suggestions is made easier by that alone. Second, everyone takes the same action by manipulating other characters so no one feels singled out when their character is targeted. Then there is the important aspect of asking if the player accepts this dictated action. This act of asking is echoed at the end of each scene when the scribe describes a tragedy to befall all the characters in the scene. The scribe describes what the tragedy will do to a specific character and then asks the player if the character “will succumb to the tragedy.” The player has the ability to say yes or no. What this system does, in effect, is make it so that two players need to agree to any significant action within the scene. And rather than structuring it so that you ask another player for permission to make your own character do something, the designer structured it in a way that feels more natural to get someone else’s permission. Behind all this negotiating, to give the negotiations weight and the resolution system meaning when it is used, is a token system. Each player begins with a small number of tokens. You must use a token (if you have one) to puppet a character or create an event, and then if your proposal is rejected, you can use tokens to increase your chance of winning the resolution. These tokens, however, do not create an economy because you do not give your tokens to other players or win their tokens from them. Instead, tokens that players bid go to what is called the “Tragedy Pile,” where, at the scene’s conclusion, the tokens are used to determine how many died in the tragic event that concludes each scene. The more contention between players, the more dramatic the scene can be assumed to be, and this drama naturally results in a higher death toll. And since tokens can be gained as play goes on, they make for a natural pacing and escalation mechanism as more tokens are spent in later scenes to allow for more drama and result in greater tragic loss. When a scene concludes and the bodies are counted, everything is summarized on the map through pictures. The elements from the scene are sketched onto the map as are the symbols for which cultures were involved in the scene. The tragic end is also represented pictorially, and each token that ended in the Tragedy Pile is represented with a symbol from the culture that the dead belonged to. At the end of the game, then, the map is an artifact with the entire history of the game represented on it, from the summaries of the cultures to the events of the four scenes. Every aspect of the game is thoughtfully constructed. I love the way the game gives productive and inspiring prompts while still trusting in the imaginations of the players. I love the way that scenes unfold with this interesting give and take between players that actively affect the dramatic outcome of the scene. I love the way the GMing responsibilities are spread out in a scene to allow everyone to be a player and no one to be an arbiter. And I love the nod toward the politics of history in the way the game ends. Once the 3 or 4 scenes have played out and the dead are counted, there is a system for finding out who won the war. Once that is determined, each player takes turns in a kind of epilogue. In the epilogue someone says how one of the traits from the culture that lost contributed to that loss. Someone says how one of the traits from the culture that triumphed contributed to their triumph. And finally, someone details how the winning culture’s traits has made the world a better place in the years following the war. The players who a moment ago were impartial scribes trying to discover what happened have become the descendants of the victors of that war and are creating the teleological arc from that victory to now, explaining how the winners and losers were determined by their very traits, and how the winners have benefited the world through their winning. It’s an incredible representation of the fact that history is written by the winners. If the game did nothing else, this aspect would impress me. But it does so much more, and I’m excited to bring this game to the table. I promised the friend who sent me the physical cards that I would write up an actual play report when I play, so I’ll be sure to share that here too as a follow up to this post.  Somehow Vincent Baker keeps creating incredible games. I’m never shocked by what he puts out, but I am often in awe. There are artists in every medium whose work you feel resonates with your soul more powerfully than other works, and something about the way I think about stories and gaming is deeply thrilled by the work Vincent puts out. But if you’re here on my website, you undoubtedly already know that. If you follow Vincent’s Itch.io page, or if you back his patreon, or if you follow his Twitter, you will have seen that he has put out a set of games recently that have one player and a pair of “volunteers” who take several of the jobs of the traditional GM. The first such game he published was “The Wizard’s Grimoire,” which he created for a game jam. Shortly after that he created “The True and Preposterous Journey of Half-a-Fool” for another game jam, and then “The Barbarian’s Bloody Quest” as a complementary piece to “The Wizard’s Grimoire.” In “The Wizard’s Grimoire,” the player creates a “conjurer, scholar, rogue, and ambitious minor wizard” (that’s one character) who is “bold, cunning, virtuous, and ambitious, in measure,” and who has come into possession of “The Signature of Aibesta of the Two Courts,” being the grimoire of said Aibesta. To create your character, you have to answer a set of six questions. Each question presents a situation and a pair of responses, and which stat you mark is determined by which response you choose. For example: Suppose that you come upon an enemy helpless and alone. Do you strike swiftly, or announce yourself and give your enemy an opportunity to explain themselves or make right? If the former, tally 1 to bold. If the latter, tally 1 to virtuous (1) In this way, because of the options the questions give you, you end up with having scores that range from 0 to 3 in four stats, with the points between them totaling 6, and no more than one stat having a 0 and no more than one stat having a 3. When I played, I ended up with a wizard who had a virtuous of 0, bold of 1, ambitious of 2, and cunning of 3. It is a super cool way to create stats because you have something specific to look at (your imagined character reactions to imagined situations) as opposed to just juggling numbers. If you don’t like the numbers, of course, you can go back and retool your answers, but in doing so, you have to be able to imagine your character taking those actions, so your image of the character will necessarily have to match the numbers as they fall on your character sheet. It’s fun, easy, and effective. What more could you ask for? Your character has 7 “exertions,” or what would be called “moves” in Apocalypse World: You are able, as are all living things, to exert yourself upon your surroundings, against your enemies, and alongside your allies (1). Essentially, you can read a person, use magic, read a situation, exert yourself physically, do something sneakily, act violently, or endure whatever befalls you, which Vincent calls “submitting to circumstance.” Each move uses your stats to calculate your move score, and each ends up being between 1 and 5. When you exert yourself (make a move), you roll a single six-sided die. If you roll your target number for that act or lower, you hit. If you don’t, you miss. For example, all wizards start with an exert yourself magically rating of 1. So if you attempt to use magic, you have to roll a 1 to hit. Each exertion is written out as a move, telling you what to do on a hit and what to tell your volunteers on a miss (more on that in a moment). One of my favorite features of this system is the clever way that Vincent uses pick lists with this single die roll. When you exert yourself empathetically to study and understand someone (i.e. read a person), you have a pick list of four questions you can ask. But you can only ask as many questions as the number you rolled. So, if you have an exert yourself empathetically rating of 4, you hit on a 1-4 and miss on a 5-6 and ask a number of questions on a hit equal to that roll. But if you only have a rating of 2, even on a hit, you can never ask more than two questions, because your character is just not that good at exerting themself empathetically. It’s awesome and clever and I love it and want to name it George. Your goal as a player (it’s a Baker game; of course you have a stated goal) is to see yourself into danger in pursuit of ambitions, and maybe back out again. Not only to take the bad with the good, take setbacks with accomplishments, but to seek danger, failure, and misadventure out, play toward it (1) Yes, that’s just a more fun way to play, but for this game it is absolutely necessary, because in this game, the player is driving all the action, and the volunteers are tasked with merely responding to what you do. It is never incumbent upon them to say anything unprompted. Here’s how the text explains it: For each session, you’ll need to find two friends who’ll volunteer to play against you. They can be different volunteers each time; it’s your responsibility to bring them up to speed and give them what they need to know in order to play. Be sure to hand them a copy of the ‘Volunteer’s Guide,’ and put ‘A Bestiary’ out for them too (2). In that Volunteer Guide, volunteers are thanked for playing, and told: You’re doing me a favor just by playing, so you don’t have to worry about winning or losing the game. Your goal is just to say things that you personally, find honestly entertaining. . . . Play then is driven by the player saying “I do x,” and then asking questions, leading or otherwise and letting the volunteers make up whatever they want. The player has to seek out trouble because it’s not incumbent upon the volunteers to create trouble. In fact, the player needs to come up with fun trouble to entice her friends to come up with fun responses. This act of flipping the wheel on the narrative car so that the players are by default the drivers and the “GMs” are by default merely responding is what makes this game so amazing. It’s like the perfect training ground for players to make their character a true protagonist driving the action. And it’s the perfect way to bring in friends who are RPG-curious by asking them to play with zero pressure and letting them just make up fun stuff and quit whenever they want out. And they have another volunteer with them so there is no pressure on them to be entirely responsible for anything. You could of course play this as a two person game with someone who doesn’t need the extra volunteer (which is how my wife and I have been playing), and I can see this being played with 4 or 5 volunteers each enjoying the sport of getting the player’s character into a worse and worse bind. The other brilliant part (so many brilliant parts!) of the game is that it is designed for, essentially, campaign play. The titular grimoire has sections that you as the player aren’t allowed to read until your character unlocks them. Presumably your skills at magic improve, what you can do with magic expands, and you run into all kinds of story seeds and trouble. The grimoire pages have specific things you need to do to unlock each section, and merely unlocking a section will take several sessions of play, which means that you have a LOT of playing you can do from these mere 11 pages of game. To make matters even sweeter, Vincent released an expansion grimoire called “The Three Scrolls of Jorvelte of the Wild Crown,” which comes with the game if you purchase it on his itch.io page. The other bit of brilliance is the page of “Spawning Circumstances.” These are 14 starting situations that you pick from for the first 14 or so sessions. Each one puts your wizard in the middle of action facing a situations that demands a reaction from you. In this way, the creative burden of getting things moving is lifted from your shoulders by the game so you can start giving your volunteers things to react to without sweating about it. Once you are underway, of course, you can create your own starting situations as your wizard has progressed and knows more about the world and what they want. It is a perfect pick-up-and-play game with tons of fun, inspirational material to get everyone on the same page and having a blast. My wife and I are taking turns, she playing the Barbarian version of the game (“The Barbarian’s Bloody Quest,” which also comes in the same itch.io purchase, and in which the barbarian is hunting down wizards in search of the wizard who killed his parents) on her turns, and I playing the wizard on mine. Both our characters exist in the same world, but our paths won’t be crossing (at least not for a long time). We have some sessions that are only 20 minutes long and some that are an hour and a half, depending on your energy and the way the dice rolls and our luck holds out. I’ll tell you what I want, what I really really want. I want to be able to play this game in restaurants with my friends. I want to be able to play it with folks when we meet up to have a picnic and throw a frisbee. I want a card version of this game in which all the information is broken up into cards so that I can carry them around in a pack with a d6 and bust it out whenever there’s the time and inclination. A card for each exertion. Printable card-sized character sheets. The Volunteer Guide and Bestiary information on cards. A card for each section of the grimoire. A card with each spawning circumstance. Look at the cards, tell a story, roll the die, laugh, ad infinitum.  After I finished Dictionary of Mu, I had Sorcerer on the brain and wanted to see another setting supplement to compare the Dictionary with. I had purchased of copy of Jared Sorensen’s “Schism” a while back and figured now was the perfect time to explore it. The strength of this setting is the ferocity of Sorensen’s vision. This game presents a harsh world with protagonists who have been brutalized, tortured, experimented upon, outcast, used, and dismissed. The players play characters who have health-ruining psychic powers that isolate them from the rest of humanity and make them prey for those who wish to use their powers for their own ends. Sorensen describes the game’s ideal play in chapter six: Games should be brief and intense. The characters should never be given a chance to rest of plan their next move. There should be an ever-present sense that the walls are closing in, even if this feeling is purely imagined. Use confusion and chaos to heighten paranoia. Pit character against character and have them face awful choices (29) And here are a collection of phrases Sorensen uses to describe how the GM should describe the world throughout play: The key to Schism is alienation. The world should feel familiar but slightly ‘off,’ as if turned one degree from reality. At times, the city should have a strange and desolate atmosphere, as if large segments of the populace were just lifted from the earth. . . . Put the characters in the midst of a crowd and try to make them understand how alone they really are. Don’t describe color or texture. Focus on details that are so magnified and out-of-scale that they become meaningless. Make comparisons between the city and the human body . . . so that the characters will constantly wonder if their perceptions are accurate or influenced by some strange force. . . . Indeed, one might. I quoted that section at length because I think it exemplifies some of Sorensen’s best writing and captures the heart of what feelings he wants this game to evoke in play. And I think it’s that strong vision that makes readers remember this game so strongly and fondly. The actual rules are cool, and it is interesting how much it changes Sorcerer’s central mechanics. Demons are not demons in this game, but the psychic powers that the PCs wield. They do not have independent characteristics or desires or needs. Instead, they are a well-conceived and delineated list of powers that all have a price to pay. The powers are not statted up like demons; the only stat they have is “power” which is derived from the PC’s “origin” stat, which replaces the “lore” stat in the original game. Players decide how their character got their powers or first discovered they had powers and give it a score just as lore has a score. That origin stat become the power stat for each psychic power the PC wields. Your cover is how you are being used or how you are employing yourself by using your power, and instead of having covens, each PC starts play belonging to a cabal, either by force or by choice. The cabal is central to the game. In the sixth chapter, Sorensen lays out his vision for how he expects most games of “Schism” will go. In this vision, characters begin as part of a cabal and then discover how the cabal is using them. They then have to escape from the cabal and are consequently hunted by the cabal. As they use their powers and face their immediate problems, the PCs’ humanity plummets and the character dies according to play. In fact, the player is instructed to imagine their character’s death during character creation. Players are not beholden to this vision, but it gets them thinking of their character’s arc from the moment of their birth. When the character’s humanity hits zero, the player gets a session to bring that character to a satisfying death, giving them a chance to go down swinging, seeking or rejecting redemption. It’s a neat interpretation of the Sorcerer system, and it shows how far the system can be used to tell the story of powerful characters who have to decide how far they will go to get the thing they want or do the thing they want to do. Naturally, I have gone back to reread Sorcerer after reading these supplements and am finding even more there than the last time I read it. I can see why it inspired so many interpretations by so many designers.  Judd Karlman reprinted his Dictionary of Mu in late 2018, and I received my copy early this year. I had a ton of other books on my to-read stack, so the Dictionary ended up on my gaming shelf. Two weeks ago, however, I discovered Judd’s recent podcast, “Daydreaming about Dragons,” and I found myself enjoying his voice and perspective so much that I pulled the Dictionary off the shelf and moved it to the top of the pile. And I’m glad I did. Dictionary of Mu is a supplement for Ron Edward’s Sorcerer, which means that it essentially is a setting with its own rules particular to that setting. The supplement takes the form of, surprise surprise, a dictionary, covering the various locations, events, factions, and personae in alphabetical order, so that the world comes into focus through definitions and references between entries. Occasionally, the conceit is laid aside so that the author can address how the rules of play are affected by the narrative elements in the entry. Similarly, demons and sorcerers are statted up to allow for easy incorporation of those figures into your own game. Cleverly, Karlman gives his dictionary a narrator, Oghma, son of Oghma, who hails from the city of Mu’s Bed. Oghma, who refers to himself in the third person only, is an old and cynical man who warns his reader about the dangers of the world and points out where his knowledge comes from first hand experience and where it founded only on rumors and stories. His marginalia makes the story that unfolds three dimensional and flavorful. The world described is the world of Marr’d, a harsh red planet that is a fantasy version of our Mars. While no map is given, the geographic features and their rough relationships to each other, are detailed, named, and populated in the dictionary. There are feline humanoids on the Chryse Plains; a gorilla-like people who mine Mount Olymon; the great city of Mu’s Bed located near the canyon called Mariner’s Gash, ruled over by a witch-king; and the red wastes where no one dwells. There are religions and legends, slavers and lost sciences, and a whole world sketched with enough inspiration to set your imagination to work without bogging you down with details and canon. It’s smart and engaging and full of possibilities. But the book is of course more than just setting material. To use it in a Sorcerer game, the text defines humanity as “hope for the future” (146), and the sorcerers are those characters ambitious enough to try to make that future a reality, but powerful and dangerous enough to leave destruction in their wake. Demons are defined as “the spirits of the dead,” and Marr’d is brimming with said dead spirits. Even forgotten ideas and notions can be spirits. The books gives you whole new lists of trait descriptors to fit (and help define) the world. The book relies on (and makes use of) the added rules that Edwards introduces in the first Sorcerer supplement, Sorcerer & Sword, so if you’re planning on planning, have your copy handy. My favorite part of the book are the little flavorful additions that Karlman has thrown in. In the text itself, Oghma encourages whoever is reading his dictionary to make further marginalia in the book so that a complete telling of Marr’d can exist. Karlman brings this feature into play with his advancement rules: Sorcerer characters advance just as stated on page 42 of Sorcerer but with one difference, they must add an entry to the dictionary before the advancement roll is made. More entries can be added if the player wishes. The write-up must be a hard-copy (or easily printable is the GM gives permission for emailed entries), so the GM can tuck it into the Dictionary, compiling a batch of definitions that will outline your campaign and add to Oghma’s labors (141). That’s just cool as hell. Additionally, When ten post-game definitions of player-authored demons have been added to the Dictionary, the Devilexicon will show up in the game. . . . When twenty player-authored definitions of demons are added to the Dictionary, a new epoch will begin. The coming of the new epoch and its details are defined by the player’s kickers (142). There are humanity-affecting rules for forming friendships, becoming a hero to another P.C., and falling in love. It's a neat book, a neat world, a neat supplement, and a fun read. Whether you’re looking for inspiration, material to game with, or simply an entertaining diversion, I recommend you pick up a copy of the Dictionary of Mu. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed