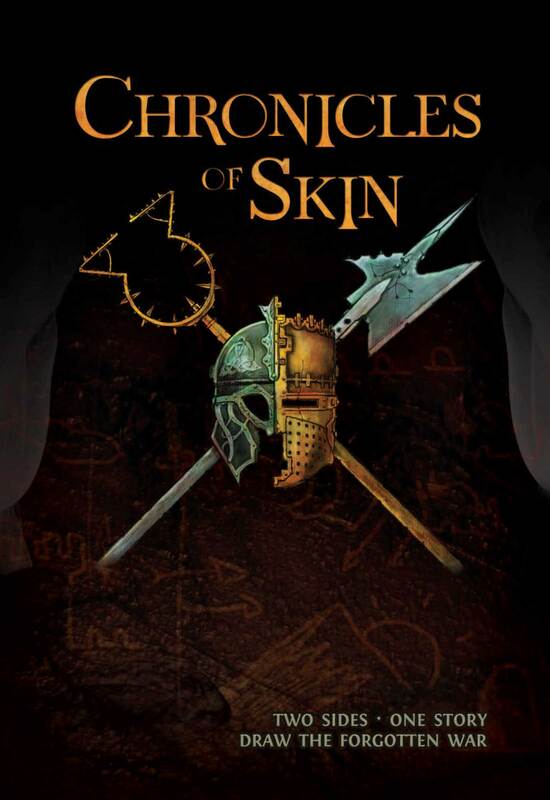

I don’t know who or what directed me to Sebastian Hickey’s 2012 storytelling/map game Chronicles of Skin. The rules of the game are available for free download at DriveThru, but the game is played with cards, and those cards are not available there. So far as I know, the game is no longer in print, and the only place I know of to get a full copy of the game is on an Italian website, but I’m assured that the cards are in the original English. If you’re looking for them (and/or a download of the Skin sheet), you can find them here: http://www.coyote-press.it/shop/skin/. The game itself guides the players in telling the forgotten history of a great civil war between two cultures who were once united under a single leader. In the first scene of play, that leader dies, and the schism begins. Play then covers two or three additional pivotal moments from the war before it is discovered who won the war and what legacy the victors have left. The central element of play is called the “skin”—this is a single page that holds the information about the two cultures at war and the 3 or 4 important locations in the realm. Players draw on the map (I call it a map, but it’s less a geographic in nature than abstract in its representation), creating pictorial representations of the character of each of the cultures and the locations of their story. As play progresses, the important events of each locations are added to the map, along with representations of the numbers who tragically fell there. At the end of play, the skin becomes an artifact of play, a complete pictorial representation of the story that unfolded in play. To make understanding the game as easy as possible, the rules include two versions of the game. The Chronical version allows players to have complete artistic control over all the elements of play. The Sketch version gives players the basic elements of the cultures and locations at the outset of play. Play itself is also more structured in the Sketch version in order to introduce players to the unusual mechanics in the game. The main mechanics during scenes come into play not when you way what the character you are playing does, but when you attempt to make another player’s character take action. This simpler version is also a quick version, making the play experience a 90-minute game rather than a 4-hour game. Unlike most basic versions that appear in RPGs, the Sketch version looks exciting to play even for experienced players. (I say “looks” because I have not been able to play the game yet, though a friend was kind enough to sell me his physical copy when I made inquiries!) I could see playing this version as a way to play quickly with new or experienced players and still have a great time. I would not feel the need to skip this version to get to the good stuff, which says a lot about the way the game is constructed. The two cultures are always called the Croen and the Iho. In Chronicle play, the players use a set of rune cards to decide the nature of each culture by deciding the following things: each culture has an “aspect,” or some defining trait; a “belief,” a superstition or prophecy that’s important to the culture; and a “rule,” a privilege or crime that dictates conduct. Once these three traits have been decided for both the Croen and the Iho, another card is used to determine the “unity,” an important person or mythological figure that is central to both cultures. The rune cards each have four images, one for each of the four categories (aspect, belief, rule, and unity)—e.g. an anchor, a crown, a spider, a flame—and the players use that symbol as inspiration for whatever trait they are determining. The rune cards are a neat prompt that gives players something tangible to bounce off when creating a trait. Moreover, any single player is responsible for one small decision so the risk of creative paralysis is minimalized, and the resulting culture is both unique and something that everyone had a hand in. The game is built around this idea of giving the players a handhold and then asking them to create something small to add to it. The locations, for example all have names: Chikugo, Seraphim, Cross, and Byzen. The players can then build off these names to create the places that they would like to see in the story. So if you want a battle on open farmland, you might create the Byzen Plains. Another might create the Chikugo Coast, or the Gates of Seraphim, or the Cross on the hill. Players can look at the traits for the Croen and Iho that they have already created as further inspiration, so if the Iho are said to be fire-eating enchanters, a player might be inspired to create Mount Seraphim, an active volcano and a holy mecca to the Iho. First the game gives you something, then you build on it, then it gives you something more, and you have that and everything that came before to build from. Things grow organically and creativity leads to more creativity. Play itself takes the form of a scene at each location on the map. Players take turns being the “scribe.” The scribe has certain responsibilities that a GM might have in a traditional RPG. The scribe sets the scene and decides which of the two cultures that scene will be about. Then, once the scene is set, each player flips over a character card, and the character card tells them a bit about the character and leaves the player to fill in the detail. The card gives you a name, a general rank (meaning high rank, medium rank, or low rank) in the social order, and then names a specific cultural trait and notes whether that character embodies (or benefits from) that trait or rejects (or is negatively affected by) that trait. For example, a player might flip over Babyss, a low ranking Iho who supports, embodies, or benefits by the Iho aspect. That gives you a lot of information to piece together a character who would belong in the scene the scribe has set. You know who they are, where they stand in the power structure (especially in relation to the other characters), and you know what they believe in and embrace or what they reject and fight against. The rules for play are stricter in the Sketch version than in the Chronicle Version, but in both versions players take their primary actions by either choosing to “puppet” another character or by introducing an “event” that happens within the scene that then requires another character to be “puppetted” in response. To “puppet” is merely to tell another player what you want their character to do. The player can either accept this action or reject it. If the action is accepted, it happens. If rejected, there is a resolution mechanic that decides if the action happens or not. All of this means that characters are handled very differently than traditional RPG systems. First, players play 3 or 4 characters in the course of the game, and they manipulate other players’ characters. It’s a clever way to make sure that everyone is invested in what every character says and does without letting players step on each other’s toes in gameplay. The secret to making this work is to have a functional system of negotiating between players. First, because players are always playing different characters, they have no reason to be overly invested in the actions of this particular characters, so agreeing to another player’s suggestions is made easier by that alone. Second, everyone takes the same action by manipulating other characters so no one feels singled out when their character is targeted. Then there is the important aspect of asking if the player accepts this dictated action. This act of asking is echoed at the end of each scene when the scribe describes a tragedy to befall all the characters in the scene. The scribe describes what the tragedy will do to a specific character and then asks the player if the character “will succumb to the tragedy.” The player has the ability to say yes or no. What this system does, in effect, is make it so that two players need to agree to any significant action within the scene. And rather than structuring it so that you ask another player for permission to make your own character do something, the designer structured it in a way that feels more natural to get someone else’s permission. Behind all this negotiating, to give the negotiations weight and the resolution system meaning when it is used, is a token system. Each player begins with a small number of tokens. You must use a token (if you have one) to puppet a character or create an event, and then if your proposal is rejected, you can use tokens to increase your chance of winning the resolution. These tokens, however, do not create an economy because you do not give your tokens to other players or win their tokens from them. Instead, tokens that players bid go to what is called the “Tragedy Pile,” where, at the scene’s conclusion, the tokens are used to determine how many died in the tragic event that concludes each scene. The more contention between players, the more dramatic the scene can be assumed to be, and this drama naturally results in a higher death toll. And since tokens can be gained as play goes on, they make for a natural pacing and escalation mechanism as more tokens are spent in later scenes to allow for more drama and result in greater tragic loss. When a scene concludes and the bodies are counted, everything is summarized on the map through pictures. The elements from the scene are sketched onto the map as are the symbols for which cultures were involved in the scene. The tragic end is also represented pictorially, and each token that ended in the Tragedy Pile is represented with a symbol from the culture that the dead belonged to. At the end of the game, then, the map is an artifact with the entire history of the game represented on it, from the summaries of the cultures to the events of the four scenes. Every aspect of the game is thoughtfully constructed. I love the way the game gives productive and inspiring prompts while still trusting in the imaginations of the players. I love the way that scenes unfold with this interesting give and take between players that actively affect the dramatic outcome of the scene. I love the way the GMing responsibilities are spread out in a scene to allow everyone to be a player and no one to be an arbiter. And I love the nod toward the politics of history in the way the game ends. Once the 3 or 4 scenes have played out and the dead are counted, there is a system for finding out who won the war. Once that is determined, each player takes turns in a kind of epilogue. In the epilogue someone says how one of the traits from the culture that lost contributed to that loss. Someone says how one of the traits from the culture that triumphed contributed to their triumph. And finally, someone details how the winning culture’s traits has made the world a better place in the years following the war. The players who a moment ago were impartial scribes trying to discover what happened have become the descendants of the victors of that war and are creating the teleological arc from that victory to now, explaining how the winners and losers were determined by their very traits, and how the winners have benefited the world through their winning. It’s an incredible representation of the fact that history is written by the winners. If the game did nothing else, this aspect would impress me. But it does so much more, and I’m excited to bring this game to the table. I promised the friend who sent me the physical cards that I would write up an actual play report when I play, so I’ll be sure to share that here too as a follow up to this post.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed