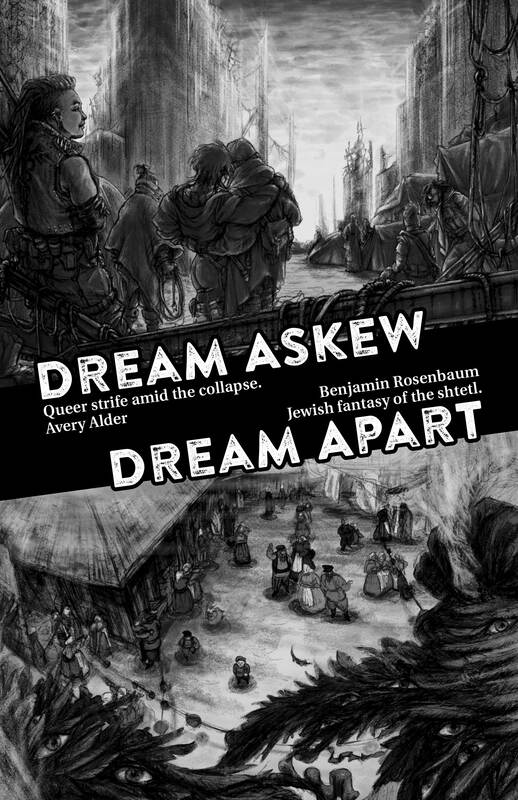

I’m looking today at the 2018 publication of Avery Alder’s Dream Askew and Benjamin Rosenbaum’s Dream Apart. This is a look at the text and mechanics, not a review or play report. In fact, I have not played either game, so take that for what it’s worth. The two games in the collection are presented at “two points [that] make a line” (161)., and the book devotes a chapter at the end of the book to creating your own game using the same system. The uniting similarity in the subject matter of these games are that they create stories “about marginalized groups establishing an independent community just outside the boundaries of a dominant culture” (161). Alder’s poetic name for this type of story is “belonging outside belonging.” In Dream Askew, players play characters in a post-apocalyptic quee community that exists on the edges of “the society intact.” In Dream Apart, players play members of a fantastical 19th-century Eastern European shtetl. Dream Askew was originally a hack of the Bakers’s Apocalypse World, and it still wears that heritage on its sleeve, or, its playbooks. But the belonging outside of belonging system is markedly different from the other games powered by the Apocalypse. First, there is no GM or MC (or there are many GMs and MCs if you prefer to look at it that way), and second, there are no dice. Alder calls the system, for obvious reasons, “no dice, no masters.” Replacing the dice is a simple token economy. On each playbook characters have a list of strong, regular, and weak moves. Any time a character makes a weak move, the player gets a token, and any time the character makes a strong move, the player must spend a token. Regular moves neither gain nor require tokens. Weak moves “show us your character’s vulnerability, folly, or even just plain rotten luck,” and strong moves “are the moments when your character’s skill, power, astute planning, and good luck come to bear and transform a situation” (31). Weak moves “illuminate how the character role copes with stress, fear, and scarcity,” while strong moves “showcase how a character claims power, what instincts they have well-honed, and what value they bring to their community” (166). Each character also has a “lure,” which encourages other players to have their characters interact with your character in a specific way. For example, the stitcher’s lure says, “whenever someone comes to you with something precious that needs fixing, they gain a token.” All lures reward players with tokens. In lieu of an MC, these games each provide six “setting elements,” which tell the players what aspects of the world are important to each game. The setting elements are picked up and put down as needed, with each player being responsible for only one element at a time. The elements are a neat design. Whenever an element is picked up for the first time, including at the start of play, the player who picks it up marks two “desires” from a pick list, which defines the specific nature of that element in this particular game we’re playing. For example, the pick list of desires for the setting element “Outlying Gangs” in Dream Askew is this: “territory, unspoken fealty, splendor, the smell of fear, home-cooked meals, mutant blood, somewhere safe to sleep.” So every time you play Dream Askew, there will be outlying gangs at play, but the nature of those gangs will shift each game as one player characterizes them with two items taken from the list. It’s a great way to define the element and tonal range of that element while at the same time allowing room for taste and, of course, replayability. Setting element playsheets also have a short list of moves to help players figure out how to have the setting express itself in the fiction. There are a ton of things to turn over and analyze here, but I want to jump to what is most surprising to me. The up-to-now standard way of doing things in GMless/GMful games is that the system must take over some of the duties that have traditionally belonged to the GM, such as spotlight control and scene construction authority. Many games have relied on turn taking to ensure that each character gets an equal number of scenes and to designate who is responsible to setting each scene. No such system exists when you’re “playing the dream.” Players are encouraged to begin play by “idle dreaming’: This is the time for questions and curiosity, for tangents and musings. Talk about whatever is interesting, or unknown, or scary, or beautiful about this place that you’re building together. Make up details about the landscape, its history, and its residents. Setup becomes play, one flowing directly into the next (24) Eventually the process of ideal dreaming results in the players finding a scene they want to play out or an area of the world they want to explore through play. The players work out for themselves which scene they will play and where it will begin. There are no mechanics in place for who speaks when to establish what in the fiction. The expected (and required) negotiations rely on players being generous with each other and fans of the other characters, which is what many elements of the design are made to do, create that space of shared kindness, respect, and curiosity. In addition to have no system for scene creation, there is no system for who talks when as the scene unfolds. If your character is in a scene you can make their moves. If the setting element you hold is relevant, you can make setting moves, and if the setting element you hold is not relevant, you can look at the unused setting elements to see if they are and pick them up instead. In addition, players can ask questions and throw out suggests at any time. The character playbooks and setting elements are about what to say, not when to say it. Even Archipelago III has a more defined system for when and what players can say through its ritual phrases. The complete lack of rules governing the conversation is shocking to me because it is so unusual. But it makes perfect sense for telling this kind of story, right? The world of Dream Askew has the possibility of being anarchic (in the political sense) and that is, I’d argue, the ideal state of things, where there is no power structure but equality and the rules that govern are those of respect, kindness, and love. Alder’s system works to create that at the table, or at least create the space for that to happen at the table. Alder makes sure there are safety tools in place, allowing players to pause play to deal with problematic content, encouraging players to ask questions so that they understand game concepts or concepts in the fiction that are unclear to them, and permitting players to gently correct each other to share subject information during play. In addition to these tools, each game comes with a recipe related to the game so that players can eat together and connect as a group of human beings before playing the game. For the game to work smoothly and safely, players much have the means to feel safe, comfortable, and united to some degree. Even removing the dice is to an extent a safety tool. Your character can only enter into trouble and hard times as you dictate them. You say when they are weak and you say when they are strong. It’s a cool design. The vulnerability of the design is of course the same vulnerability of anarchic societies. They are vulnerable to strong personalities taking control. They are vulnerable to a group of timid players tiptoeing around scenes, not wanting to mess things up or get things too dirty. Every game system is of course vulnerable to players; that’s part of the thrill of our hobby. Players are always what makes the game fantastic or disappointing, and a system needs to support players to be at their best and make it difficult for them to be at their worst even if it can’t stop them. There is a vast amount of trust in Alder’s design, and it puts that trust in its players and attempts to build that trust between its players, and then it relies on that trust to make the game the experience everyone wants it to be. My guess is experience with the system will vary widely, both between groups and between individuals. For some, it will be everything they have been looking for in an RPG; for others it won’t provide the gas and random inputs they want to create stories that threaten to run out of their control. But that’s a good place for a game to be, or any piece of art. Those who love the work will find it and be thankful it’s there. Those who don’t have plenty of other places to turn to.

5 Comments

I, personally, adore Dream Apart, but am not so interested in Dream Askew—just, content-wise, the shtetl-fantasy was something I didn't know how much I needed until I had it, and the system perfectly conveys what I need from it.

Reply

Jason D'Angelo

6/2/2019 10:26:41 am

Yeah, those fall in love moves are beautiful! The whole construction of the moves in Dream Apart look on paper (and I say that of course because I haven't played) to be really well done!

Reply

I've been thinking about this, and struggling with how to convey it. Yes, it has surprising moments, moments when someone else looks at their moves and does one that isn't how you expected them to respond in the moment and it sends you off on a whole other tack. But it's hard to convey, because what you get in the end is solidly a shtetl-fantasy story, that feels like you could have read it somewhere. 7/17/2025 05:53:12 am

This was a fascinating read! Avery Alder's Dream Askew offers such a unique take on role-playing games, breaking traditional rules and embracing shared storytelling. It’s exciting to see games that challenge norms and foster creativity. Thanks for highlighting this brilliant work!

Reply

7/18/2025 01:59:23 am

Fascinating read! I really enjoyed your deep dive into Dream Askew and its approach to collaborative storytelling. The focus on community and shared power at the table is refreshing. Thanks for highlighting such a unique and thought-provoking RPG experience!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed