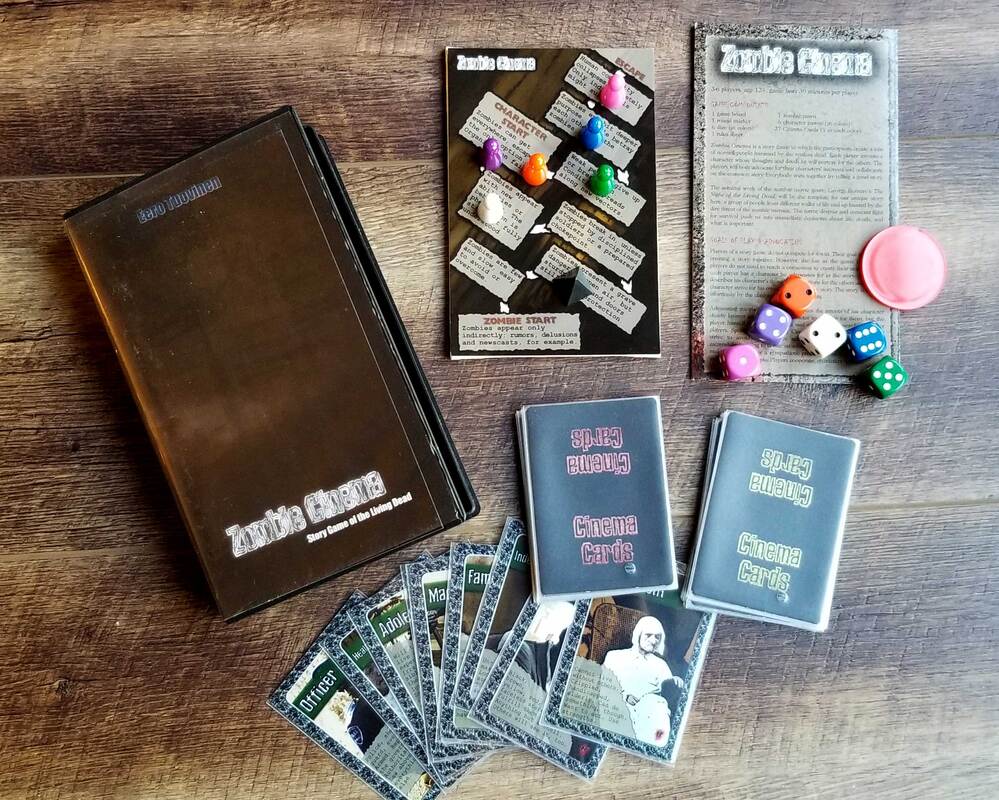

Eero Tuovinen’s Zombie Cinema was published in 2008, but I got my copy a few years ago from Indie Press Revolution, so it seems to still be in print. The game comes in a VHS case, and presents as a small board game that’s simultaneously a story game. The rules are short and direct, and the board is pasted onto a thin 5x7 canvas. The game is intended for 3-6 players and it plays out in a single session. The story you tell through play is that of a zombie survival horror film, Tuovinen taking his primary inspiration from George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. The game has some really neat mechanics, but it is a product of its day, which seems weird to say a mere decade later. Let’s start with the cool stuff. The board of the game has a single track. The zombie token begins at the earliest point of the track, and the player tokens begin 5 spaces ahead of the zombies and 4 spaces from the end. Each space describes the limits of the zombies’ power, so when the zombies are in the first space, we are told that “Zombies appear only indirectly: rumors, delusions, and newscasts, for example.” As the zombie token moves forward through play, the zombies appear first individually, slow, and limited, and as they progress, their numbers grow as do their determination, effect, and abilities. It’s a great way to pace the zombie pressure to match the typical zombie pic. The other cool thing the board allows you to do, and this is for me the golden tech of the game, is that scenes resolve by moving players forward, backwards, or nowhere at all. The game is GMless/GMful, and players take turns setting scenes and pushing for their own character’s survival. Each scene can potentially end in a conflict between characters. If it does, the characters who win the conflict get to move a step forward, and the losers have to take a step backwards. This means that your survival is dependent upon pushing others under the zombie bus. That’s cool and on brand. Conflict resolution is also neat. Each player has a uniquely-colored token and a matching uniquely-colored d6. At the time of conflict, the player initiating the conflict puts their dice forward. If the other player yields to the first player’s demands, they hold their dice and no conflict occurs. If the other player wishes to engage in the conflict, they too put their dice forward. Then the other players have a chance to affect the outcome of the conflict. Non-involved players can either pass, ally themselves, or support a side. If they pass, they hold onto their dice and stay out of the conflict. No matter how the conflict resolves, that player’s character is staying put. If they ally themselves, they add their dice to one side of the conflict. In doing so, they tie their fate (and token’s movement) to the side they ally themselves with. To support, the player places their die on top of the side they are supporting. This is a meta-action, in that the support is the player expressing their support for a side, not the character. The character doesn’t have to even be in the scene (or still alive) for the player to support one character. The supporting player’s character’s token is not affected by the outcome of the roll. Then both sides roll their pools and the player with the highest single die wins. The die mechanic is a good way to keep everyone involved and to let each player decide how they want to participate. The system also means that if you want to save your character, you need to seek out and participate in the conflicts in the scenes. It’s a smart way to make players happily create the drama the game wants to see. The zombies move ahead every round and can never be sent back, so there is an 8-round clock on the game. In addition, in any conflict in which the dice tie, the zombies take another step forward, so the odds say a game will average 6-7 rounds, with a minimum of 5. The zombies, combined with their naturally increasing threat levels, makes for an excellent timer. The main troubles from which the game suffers, in my opinion, is that it does nothing to share the heavy fictional lifting with the players. This is what I mean by the game being a product of its time. In the last 10 years, indie designers have learned all kinds of techniques to help create character relationships and material for scenes. Let’s start with character creation. The game has three sets of cards (9 in each set, 27 all together). To create characters, players draw one card from each set and will have a history, demeaner, and general appearance. Seems good. But the game does nothing to tie the characters together, so unless you have experienced players who know that the drama will benefit from ties and past relationship, expectations, and desires, you will end up with a game of strangers with nothing to talk about in any given scene except the zombies outside their door. Similarly, scene creation is left to each player during their turn with the simple prompt: “The active player makes the call on the time, location and participants of the scene like a shot in a movie.” That’s it. That’s all you’re given. There are no mechanics to help with the pacing of your story beyond the abilities of the zombies, nothing to create interpersonal drama. I can easily imagine a game in which every conflict results from character’s screaming at each other in life-and-death hysterics. It’s up to the players to create a thoughtful set of interactions, which is great is you are with experienced and thoughtful players at the top of their game. The character cards are problematic in their own way. One of the character roles is “Ethnic Minority”: “Black, brown, yellow, red, faceless stereotype. Fulfill them or not.” Yikes. I get that in white American cinema, the token character of color is a thing, but there is no reason for your game to continue that. Similarly, having that card suggests everyone else is white. Ugh. Another card is “Dependent”: “Cannot live without others. Cripples, handicapped, elderly. Can do something, though.” And of course one of your character’s defining traits can be “Mental Problems.” There’s a whole lot of cringing there. I haven’t ever played the game, and I don’t see myself ever playing it at this stage, especially with Zombie World out there. All the same, this game is designed to scratch a different itch than Zombie World does, and it has some innovative ways to get there. The problems with the game can be pretty easily solved with updated character cards, a relationship/history feature, and some basic scene-creation and conflict-creation support.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed