|

Matthew Gwinn’s The Hour Between Dog and Wolf is an innovative 2-player RPG. One player plays a serial killer and the other plays the “hero” hunting the serial killer, be that a detective, medical examiner, psychic, or whatever. The game uses the word “hero,” but it is not interested in any idealized heroic figures. Inspired by films like Se7en and shows like Criminal Minds, the game seeks to create stories in which the core tension is the psychological unraveling that hangs over the hunter and the cat-and-mouse interplay between the killer and their pursuer.

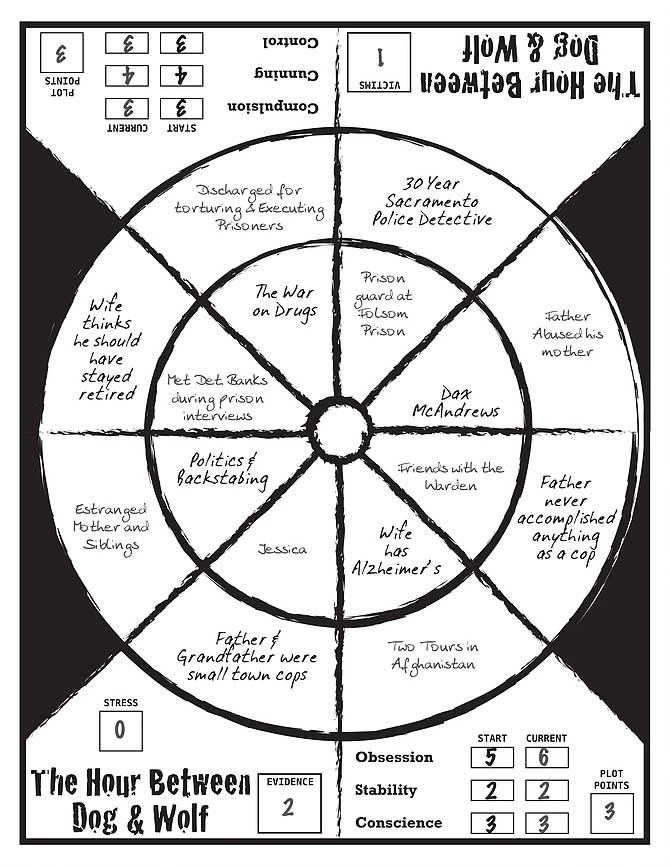

The rules themselves are fairly simple. Much of the 64-page rulebook is given over to character creation, specifically guidance for understanding and portraying your character. There are eight hero archetypes, and the book details how each investigates murders and what types of advantages and disadvantages their position and approach grants them. Even more useful – and more extensive – is the information the text provides for the killer player. To give the killer player the information they need to portray a serial killer with purpose and consistency, the text spends a long time categorizing serial killers: their methods, motivations, victims, hunting grounds, and manner of dumping bodies of past victims. Every bit of information is designed to help you make decisions about how to portray and imagine your killer. It’s time well spent. Without this guidance, players are in danger of either rehashing details from movies and books or flailing about trying to figure out what to describe next, probably both, which cuts into everybody’s fun. Beyond these fictional details, characters have a set of stats that go up and down throughout the game. The killer tracks their compulsion (the overwhelming drive to kill), cunning (the cleverness to stalk prey and avoid capture), and control (the need and ability to control and manipulate others). The hero’s stats are obsession (the overwhelming drive to catch the killer), stability (the strength of personal relationships), and conscience (the sense of morality and willingness to follow the law). In addition to these primary stats, the players track the hero’s stress (the toll taken on the hero’s mental wellbeing), the number of the killer’s victims known to the hero, and the amount of evidence collected against the killer. Once you have chosen your characters type, figured out the fictional details, and assigned stats, the final part of character creation is a cool process that links the characters with each other and maps out possible content for future scenes. Each player comes up with four aspects of their character or their lives that the player would like to explore through play. The players come up with those aspects together and share them so they both know what interests the other player. Then the players come up with and share four questions that they have about the other player’s character. Players can posit information in their questions, and in this way they help shape the characters and their relationships. For example, the killer player might pose the question, “Why are [the killer] and [the hero] friends?” or “Why is [the hero]’s relationship with her father so fraught?” So by the time you’re ready to play, you know who your character is, how they operate, what you want to learn about them through play, and what about them interests the other player. Relationships are pointed to, if not outright detailed. All you need is a murder to kick things off, which is how play itself begins. The killer player describes so aspect of the killing that begins the story. This is an opportunity for the players to agree upon the tone and level of detail that they will maintain throughout the game. If it’s going to be gory and graphic, now’s the time to establish it. If violence is going to take place mostly off screen and much of the horror veiled or alluded to, now’s the time to make that clear. By beginning with this description, the game allows this necessary conversation to occur naturally with something concrete. From here, the hero and killer take turns choosing from a list of scene types. Each scene type gives the player a chance to increase or decrease a specific stat - affecting either themselves or their opponent – by successfully achieving their goal for that scene. In this way, the killer can find themselves more compulsive or increasingly cunning, for example, and the hero can find themselves more obsessive or increasingly unstable. Over the course of the game, both characters will likely spiral out of control as they play to trigger the end game. The end game is triggered when the stats reveal that the hero has more evidence than the killer has cunning and control, or when they reveal that the killer has more victims than the hero has stability and conscience. No matter who “wins” both characters will likely find themselves in a desperate state, the hero having crossed questionable lines and sacrificed family and friends in their pursuit, the killer driven by a nearly uncontrollable compulsion to kill that will never bring the satisfaction they seek. Players choose scenes for their character depending on what stat they want to affect in order to get the ending they desire. The killer can either try to kill enough victims to outrun the hero’s stability and conscience, or the killer can try to win with a low victim count by chiseling away at the hero’s stability and conscience instead. The hero can try to gather enough evidence or instead try to undermine the killer’s cunning and control. Each scene type dictates who frames the scene and what stats are affected. The scene framer acts as the GM, controlling the whole world except for the other player’s character. The scene plays until the acting character reaches a critical point in trying to attain their goal for the scene. Each scene type pits one stat of the hero’s against a stat of the killer’s. Each player roles a number of dice equal to that stat’s ranking. The player with the highest single die wins. In this way, the players are always playing against each other even when only one of the characters appears in the scene. So for example, in a “crossing the line” scene, the hero is acting questionably (morally or legally) in hopes of gaining a two-point increase in evidence at the cost of one point of conscience. When the roll comes, the hero rolls their obsession trait against the killer’s control trait. If the killer wins, they get to increase their control and the hero’s obsession is knocked down a point. The main tool used to frame scenes is an 8X10 page called the Framing Table. At the center of the table is a target divided into three rings, with the outer two rings each divided into four parts, and the center ring a single, small ring. At the time of character creation, players write the aspects they want to explore during play into those rings, one aspect in each of the eight segments of the two outer rings. Then, when the players takes their turn, they roll a mixture of black and white dice. Of the dice that land in the target, the player locates the segment with the highest die and uses the aspect in that segment as the focus of exploration in that scene. Or not. The player has the option to ignore the dice roll and focus on whatever they want in the scene. I like the idea of the framing table in the abstract, but it seems a clumsy way to help the players find a focus in the scene. The dice can go anywhere, and the aspect might not be right for that point in the story. The rules invite you to ignore the results of the roll, which begs the question, why is it there at all? It would be much smoother to just invite the players to pick an aspect not yet examined in play and create a scene to explore it. In the end, the framing table is an idea that looks cool but that I expect causes as many problems as it solves in play itself. (Note: I haven’t yet played the game, so I’m not speaking from a position of experience on this point.) The text is clearly written, and the rules are thoroughly covered. Other than feeling that the hero archetypes should have been briefer. I felt no impatience with or confusion over the text. I was not a fan of the photographs that illustrate the text. They are well done, but they look cheap, like stills from a B-movie. The game provides great reference sheets, although I can’t find them for download online. Having a physical copy of the book, I’ll have to make photocopies from it. A minor inconvenience, but an unnecessary one, it seems to me. I am excited to get this game to the table and expect to do so soon. If any of my opinions or thoughts change after playing, I’ll add an amendment to this review.

2 Comments

2/17/2019 10:06:53 am

Thanks for the review of my game. I hope you get a chance to play it.

Reply

Jason D'Angelo

2/17/2019 08:13:48 pm

Hey Matt!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed