|

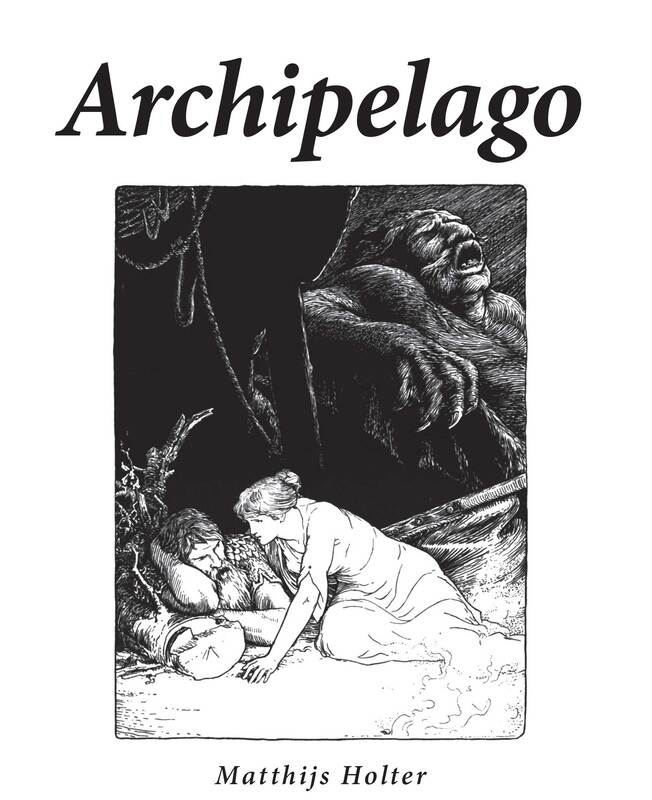

I read the third edition of Matthijs Holter’s Archipelago, the one edited and laid out by Jason Morningstar. The game is a GMful storytelling RPG designed to “capture the feeling of Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea books.”

There’s something pure in the simplicity and structure of Archipelago. Everything has its purpose and reduces the RPG elements to their most basic function in play. Every part of the game answers the question, how do a group of people harmoniously create a narrative that has direction, connections, surprises, and consistency, harnessing the creative power of everyone involved while negotiating their different visions and impulses to create something shared and appreciated by all. Character construction and world construction are about giving you what you need to create an interesting story. World construction begins with a genre and a map to put everyone on the same page. Then the players decide on what “elements” are central to the world and distribute ownership of those elements among the players so that everyone is in charge of one area. The act of deciding what elements are central to the story let’s everyone know what aspects of the world will be important to the story. Ownership exists “to make sure that the setting has integrity, that there is a uniting vision for these elements.” Additionally, five or more locations need to be named and established on the map to give players enough room to begin play while still leaving plenty to be discovered during play. Once the world is sketched out and its elements are agreed upon, characters can be created. It’s important to play that characters are created together and out loud so that ideas can be shared and that matters of tone and scope can grow organically through conversation. Each character needs to have what the game calls an “indirect relationship” with each of the other PCs. An indirect relationship simply means that our two characters have an important person, thing, or idea in common. Perhaps my father is your lover, or we both fought in the same famous battle but on opposite sides, or your sister wrote the book that is central to my cult. These relationships allow us to make whatever character excites us while still providing the groundwork for our stories to overlap and cross each other. Even if they manage not to overlap, our stories will exist in the same world and space, commenting and reflecting upon each other. Finally, each character needs to start the story in motion, so you give them a grand destiny or a driving concern. And that’s everything you need to get a story moving. The specific story you are going to tell is given direction through the use of destiny points. At the beginning of the session, after the world and characters have been created and the story is ready to commence, each player writes a “destiny point” for each of the other characters: “This is an event that will occur in the life of the character – something dramatic, significant, perhaps something that changes their life.” The player then selects one of the proposed destiny points and places it where all the other players can see. Having other players create proposed destiny points gets everyone thinking about everyone else’s characters and where they might be going. It means that as we play, I’ll have things in mind as I take on secondary characters or propose obstacles and scene details for you. In addition, having your destiny points created by the other players means that you can be surprised by the path your character is set to travel, while being able to pick the destiny point that appeals to you means that you buy in on the direction your story will go. This need to be surprised and not in full control of your character’s story is an important element of any diceless, GMful game. We see this same concern in the rules of the game that say you can never interpret your own fate or resolution cards. You get to choose who interprets the card, but not how it is interpreted or what happens to your character as a result of that interpretation. The fate cards are a collection of 12 narrative prompts that each player can turn to once per session in order to give their story some narrative juice. The resolution cards are a series of “yes, and” “yes, but” “no, and” “no but” and “perhaps” cards that can be used once per scene to decide how a character’s actions play out. The creative power of the game is in the minds of the players. The rules are constructed to tap into that power and negotiate the different impulses and desires to create something greater than any single mind would come up with, something enjoyed by all. The game employs six ritual phrases that create a shared language for the players to negotiate with the other players, allowing them to push for what they want. The phrases – “try a different way,” “describe that in detail,” “that might not be quite so easy,” “harder,” “help,” and “I’d like an interlude after that” – are strong enough to direct but too weak to control the conversation and developing narrative. You can push and pull at the story, but you can’t keep your hands on it and simply point it where you want it to go. The phrases mean that you can take chances knowing the other players can jump in if they don’t like where things are going. As a group, using the phrases, you can fine-tune your individual visions until they become a collective vision. Every rule has its place and its function. All the tools either create narrative and drive or negotiate the different visions and impulses at the table. There is nothing extraneous and nothing missing.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed