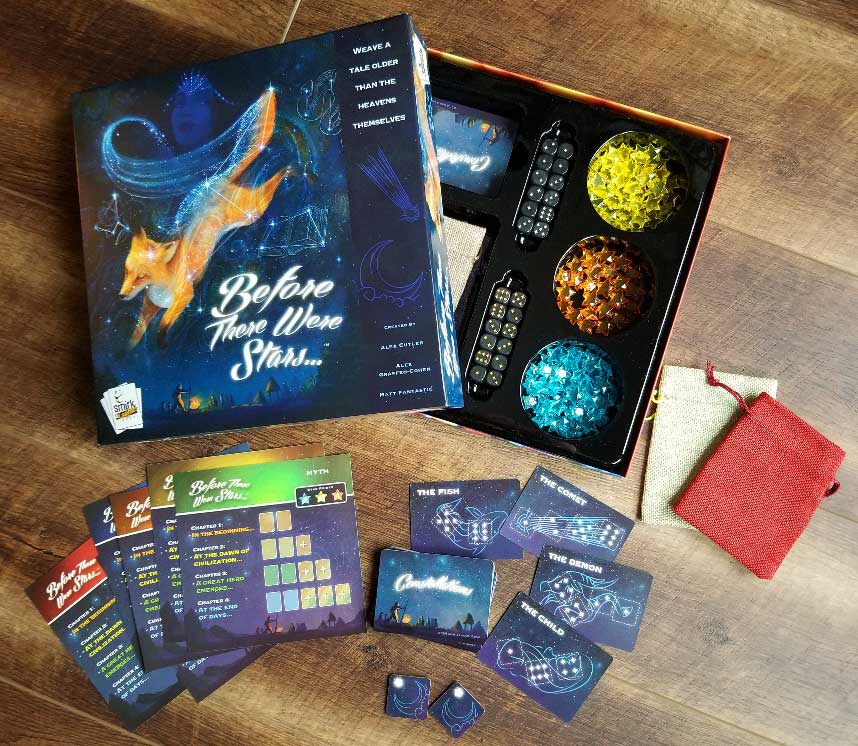

Before There Were Stars . . . is a boxed game (I suppose it’s categorized as a board game although there is no board) by Smirk & Laughter, the non-backstabbing-games division of Smirk & Dagger. I don’t normally analyze or review board games, but this game is really a story game masquerading as a board game, and it’s a cool one at that. The central component of the game is a set of constellation cards. Represented on each card is a set of two to four d6 faces, with the pips of the dice creating the stars of the constellation, around which is a sketch of the thing the constellation represents. Each constellation has a name, a narrative element to be used in the myths that you will create through game play. Some example cards are The Volcano, The Desert, The Angel, The Spy, The Chest, and The Child. Each player has a “Story Card” with four story prompts, one for each round of play. The four prompts are “In the beginning . . .” “At the dawn of civilization . . .” “A great hero emerges . . . “ and “At the end of days . . .” Each round consists of three phases. The first phase is called the stargazing phase. In the stargazing phase the top 5 cards of the constellation deck are turned face up. Players then take turns rolling 12d6 and select one of the constellations whose die faces match the dice available to you from your roll. If there are no matches available, you draw from the top of the deck. The cards chosen are replaced after each selection so that each player always has five cards for chose from. After each player has two cards, the stargazing phase ends. I like the mixture of choice and limitations that this setup provides. On a good dice roll, you can pick any of the constellations you want. On a bad roll, you get no choice at all. Usually, you’ll end up somewhere in the middle. Either way, you have reasonable constraints that create excitement and pressure on a minor scale which makes the player think critically about their choices. Further, you will naturally pay attention during other players’ rolls, especially if there is a constellation you are hoping will still be there when it’s your turn again. These pressures and constraints can lead to players creating combinations and storylines that they would never come up with without them. That element of being able to surprise yourself is critical to good story game. Or at least, it can be. Now the storytelling phase begins. Taking turns, each player takes a moment to think of the story they will tell using the two constellation cards they collected and the story prompt for that round, and one by one they tell a short, simple myth in about 60 seconds. Here’s the example from the rulebook: “In Chapter 1, Melodee has chosen the Constellation BOOK and VALLEY. She gets ready, starts the timer and begins, speaking in a voice that all can hear . . . ‘In the Beginning, the All-Mother poured all of her knowledge into a gigantic book, so that she could one day share it with her children. But as all was still void, there was nowhere to raise her family. So, she took the book in her hand and opened it at its center. The pages unfurled, forming a great valley, where her children could now grow and prosper.’” The 60 second timer is not a strict measure. Players can go way under or way over the time if they wish. The 60 seconds is a good target, in that it emphasizes that the players are not expected to develop anything overly complex or detailed, and it is designed to keep the pressure on any given story low. It seems counter-intuitive to use a timer to relieve pressure instead of building pressure, which is why I think they created a special timer app for the game. The image on the app is of people around a campfire under a star-filled sky. As the time counts down, the star wheel overhead and the sky lightens until it looks like morning when the timer reaches zero. As the timer progresses, you hear the sounds of crickets and peepers and other night animals, a kind of white noise that serves to create the atmosphere of stories told communally around a campfire. Once time is up, the night animal sounds give way to a chirping bird announcing the rising sun. All the sounds or unobtrusive and pleasant, rather than alarming. After the storytelling phase is the appreciation phase, in which the players reward the other players for the stories they told. We’ll come back to that in a minute. These three phases repeat for the four rounds. In the subsequent rounds, you select two additional constellations that you must use as the basis for your next story following the prompt for that round. But in addition, you must also re-use a minimum number of the cards you used in previous rounds. Bringing in these earlier cards allows you to stitch the elements of your myth together so that the body of your myths have internal consistency and narrative echoes. It’s a neat and easy way to unite what could otherwise be four disparate tales. Now, back to the appreciation phase. This phase amounts to a scoring system which lets the game have a “winner.” Here’s how the scoring works. There are three types of plastic stars that come with the game: blue, yellow, and gold. Each star is worth 2, 3, and 4 points, respectively. These stars sit as a pool in the middle of the table, and after each round, players get a number of stars equal to the number of players minus one. There is a chart in the rules that tells you how many and what kind of stars each player has access to depending on the number of players playing. The players then pass around color-coded cloth bags and drop a star in each bag that is not your own, essentially scoring the other players’ stories. The stars and their points are not looked at until the end of the game, so they do not act as feedback, but as unknown information. After the final appreciation round, before points are totaled up, each player gives a moon token to one other player that they feel had the “best story moment” and tells what that moment was. This is the only organized praise and spoken feedback of the game. The stars and moon are specifically said to celebrate the “best story moment” rather than the “best performance” or the “best story” so that any singularly gifted storyteller doesn’t end up with all the points. So you can point out a cool or surprising moment, a neat way to combine unexpected constellations, an awesome callback to an earlier event—whatever impresses or surprises or delights you. I really like the idea of distributing praise this way, though I’m not crazy about points being tied up with it. I get why the stars are hidden information until the end of the game. You don’t want players getting discouraged that their stories are getting few points, because that would be no fun. But that’s part of the problem with rating your fellow storytellers using points, isn’t it. As soon as points are on the table, you are asking the players to care about those points and to strive for those points. If they follow your lead, then their pleasure and purpose is wrapped up with those points. If they don’t, then the points are useless and just muddy up the gaming experience. I would rather see something like the moon token exchange happen after each round so that players are getting constant feedback and encouragement. I’m sure that that happens naturally anyway (“Oh wow, that was cool!” “I love the way you tied those together” or even stunned and impressed silence) but I’m all in favor of mechanizing that feedback. Before There Were Stars . . . is a well-designed, neat game, with sharp, simple rules and quality components and art. It’s a great quick game for players who love stories and storytelling.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed