|

There have been several kickstarters recently for RPGs for which there is no paperpack production. Why is that?

I assume there is a straightforward financial reason, but aesthetically I'm a huge fan of paperbacks and not so much of hardback books. It doesn't hurt that paperbacks are generally more affordable, but cost isn't even my primary concern. I'm hoping what I'm seeing is not a trend, and if it is that it will not continue to be a trend.

0 Comments

If you're playing a flashback episode in Apocalypse World to learn something about the characters' past relationships, would you call that a Hx crawl?

Something I've learned from reading +Jason Morningstar's Grey Ranks and Night Witches: awesome ways to make weariness and stress felt in an RPG.

It's one thing to create a weariness or stress track and let that number or set of markings guide the player in the playing of their character. It is another thing entirely to have those moments of weariness and stress have impact in the fiction so that the character is changed or impacted in a lasting way, so that the player will necessarily bring it into her conception and portrayal of that character. Grey Ranks doesn't need a weariness track because the grid tells you where you are, and play makes it painfully clear where you've been. The game has a built in death spiral that will slowly push your character to darkest corner. You can play your character however you want, but that bone-deep weariness is cooked into the fiction, and even moments of levity and hope will unavoidably sit on top of those experiences. Being Marked in Night Witches works the same way. Marks are essentially a one-way weariness track, but instead of just checking off boxes towards your doom, each check is accompanied by a slice of fiction that has worn at the soul of your pilot. As a player, you feel that moment, and as a group you acknowledge and see that moment. In both games, the horrors of war go beyond merely mechanical elements to become woven thoroughly into the fiction. You've probably already seen this, but in case you haven't (or in case you have but haven't clicked through to Lehman's and Belle's actual text), you should go and read "The Tragedy of GJ237b." Now.

RPGs are a double art form. First there is the writing itself, the presentation of information in enlightening and surprising ways that hint at the ghosts hiding in the unlit corners of the text. In there best texts there is a kind of poetry of language. There is a lot of poetry in "The Tragedy of GJ237b." Second, there is the construction of a system that reveals to us ways that the world and human interactions work. They create systems and shape human interactions that reveal to us truths about the world we live in in a way that no other art form can replicate. The best texts recognize this unique ability of the art form and harness that power. There is a lot of power in "The Tragedy of GJ237b." Originally shared by Ben Lehman - 21 comments So +Caitlynn Belle's and my game The Tragedy of GJ 237b was nominated for a Nebula award for short stories, but the nomination was rejected on the grounds that it is a game and not a short story. This, in and of itself, is completely amazing. I've been trying to have a conversation about games-as-literature for a really long time, and getting to the point where a game I co-authored is being considered as literature -- even by just a few writers -- was, already, a huge win for me. Then, one of the people who nominated it, Yoon Ha Lee (an extremely good SF writer -- you should absolutely read his novel Ninefox Gambit, it's fantastic) wrote about the experience, and why he thought it should count for a short story: https://yhlee.dreamwidth.org/2478387.html This, also, was amazing in and of itself. To have a writer of that caliber talking about my work as literature was pretty extraordinary. Then, early today, he decided to appeal to decision of the Nebula committee. And this happened, just now: https://twitter.com/TheCozyVet/status/962172278388686848 So it looks like The Tragedy of GJ237b is actually qualified for first round nominations this year. This is astonishing (I'm running out of adjectives here). Other game-like things have been nominated, mostly CYOA stories, but as far as I know this is the first time that a (sort of, kind of, maybe) role-playing game has been considered. I'm freaking thrilled. To make the text more accessible, I posted it to Medium (with Caitie's permission of course): https://medium.com/@balehman/the-tragedy-of-gj237b-928cfeae460b If you're an SFWA member, please consider nominating The Tragedy of GJ 237b in the short story category this year. Cashed in my holiday money-gifts for this week's arrivals:

+Willow Palecek's Escape from Tentacle City +Jason Morningstar's Grey Ranks +Sara Williamson & James Stuart's 183 Days +Michael Sands' Three Dooms +Anna Kreider & +Andrew Medeiros' The Watch got here just today as well! So much exciting reading and playing ahead. If only one of my clients didn't kill my weekend with a rush edit. Alas I must be patient (but damn am I tired of being patient). Hey All!

+Ron Edwards has created a new website that promises to be an incredible resource and meeting place for those who think critically about roleplaying. www.adeptplay.com has a place to post and discuss actual plays, and there are already a number of videos or Ron discussing different aspects of RPG theory. You can sign up for seminars and watch past seminars on a whole range of RPG-related topics. If you miss (or missed) what The Forge had to offer as a discussion place for thinking and talking about RPGs, you should go check Adept Play out! A move trigger I really want to have in a game with teen characters: When you ask your parents to borrow the car . . .

I imagine on a 7-9, there's a pick list that includes the tank is almost empty, you need to be sure you pick your little sister up from soccer at 4:00, or you need to run an errand while you're out. I finally got a copy of +Vincent Baker's Poison’ed and have to talk for just a moment about the first couple of paragraphs because I think it is a brilliant way to present information for a short RPG text.

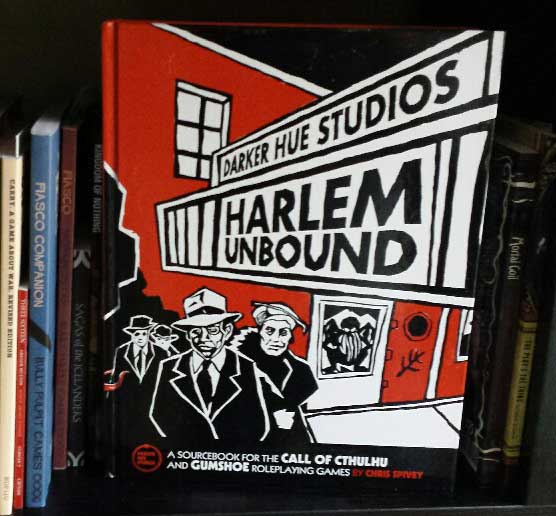

Brilliant thing the 1st: Presenting a clear, gripping, energized and energizing situation. Here’s how the game text opens: In this the Year of Our Lord 1701, did end the bloody career of the pirate Captain Jonathan Abraham Pallor, called Brimstone Jack. He did not die on the gallows, nor by the sword, nor shot in two by cannon. He died of poison, administered to him by his cook, an assassin under the King’s orders. This is what happened next. [Here “Poison’d” appears in pretty script like the title card of a movie or TV show] Drag forward the cook, the assassin Tom Reed, throw him on the deck. He’s spitting and proclaiming us dead men all, no captain no more, ship listing and hungry, and His Majesty’s Ship The Resolute even now hauls up its anchor over in Kingston Bay. Right?! This is the starting point for every game. You are pirates about the late Brimstone Jack’s ship, in the moment of a sudden power vacuum, with the assassin before you on deck declaring us all doomed, and an armed ship headed this way to capture us all. You don’t even know the rules of the game and you’re mind is already filled with possibilities wanting to know what you and your friends would do from here. The game doesn’t need to sell you on what you can do and what game play might look like—hell, you’re ready to do whatever it says to do the things that setup already suggests in your revved up imagination! And if the situation doesn’t appeal to you, you can save your energy and skip the rest of the game. And that’s it. There follows no overview of play or the system or anything else. Without any delay you are thrown into character creation. Brilliant thing the 2nd: Creating the world through character creation. The first command in character creation is this: Choose your character’s position under Brimstone Jack: Boatswain (“bosun” – sails, rigging, anchor, cables; also the day to day work of the crew) Boy (light labor, service & training) Carpenter (the soundness of the ship’s masts, yards, boats & hull, patching holes under fire) Gunnery Master (the ship’s cannons, powder & balls; the gunnery crew) Quartermaster (the ship’s purse, books & accounts, and the provisioning & quartering of the company) Sailing Master (navigation and steering the ship) Sailor (manual labor, gunnery, fighting) Surgeon (medical care of all on board) X’s Mate (eg Boatswains’s Mate, Captain’s Mate, Carpenter’s Mate, Cook’s Mate) That simple lists of position and their corresponding responsibilities and duties gives you a full overview of what is happening on the ship and how everyone is dependent on everyone else to make the ship run smoothly. We can surmise that we will need to patch holes in the hull under fire, that we will be firing the cannons, dealing with provision decisions and shortages, maneuvering the ship, fighting enemies and prey, and getting seriously wounded. It’s about giving information, but more importantly about stoking our imaginations and getting us all in the same imaginative space. If the first list tells us about the physical world of Poison’d, the next list tells us about the moral world. Which of the following sins has your character committed? Choose none, one, any or all: Adultery Blasphemy Idolatry Murder Mutiny Rape Robbery Sodomy You may count a sin twice, if your character’s commission of it has been prolonged, repeated, excessive, and unremorseful, and continues to be so even now. Okay then! Prepare yourself for some horrible, morally depraved characters to strut the stage! If this is not your thing, bail out now, because this is the moral landscape of the game, and even if you choose to go easy on the sins your character has committed, your fellow players are under no obligation to do the same. And in case you’re wondering, are there female PCs in this game, the next paragraph’s got you covered: Count it blasphemy if your character is a woman living, acting, and dressing the man. Count it twice blasphemy only if she has also somehow to fuck women as a man. Just take a moment to appreciate how much information about the world is stuffed into those two sentences. What are we, less than 10 sentences into the game? And mind you, we still don’t know anything about how to play the game! And that brings us to the third brilliant thing. Brilliant thing the 3rd: Teasing out information. The next two paragraphs are these: Devil is equal to the number of sins you’ve chosen. However, if you’ve chosen more sins than six, Devil is still 6, and if you’ve chosen fewer than two, it’s still 2. Soul is equal to 8 minus Devil. This is my favorite introduction of a stat, pretty much ever. Up to this point in the text, you have no idea if the characters will even have stats, let alone what they will be and what they will measure. Now we know Devil and Soul are two of the stats (possibly the only two at this point in our reading), and we know that Devil must represent how sinful we are, since it is bound up with how many sins we chose, and Soul is clearly representative of the opposite. Baker doesn’t have to spend any more time explaining the stats than that and we are left in a state of having information and desperately wanting more information. And the text does that section after section, item after item. The presentation of information has all the grip and tension of a well-plotted short story, or like the first quarter of a masterfully written sci-fi or fantasy novel, the part where you are making note of every suggestion and unexplained reference in hope of piecing it all together into a coherent whole. In fiction like that, the act of reading is the act of discovery; you are an active reader working to meet the author half way rather than a passive reader demanding to be spoon-fed all the details. It’s an illusory feeling of course, because the author will eventually make everything clear, but as active readers, there is a sense of satisfaction when all the threads come together and our knowledge feels hard fought and deserved. Each new concept in the game is intriguingly alluded to in one section so that when it is fully explained later, it is incredibly satisfying. Bargains, for example, start out as a vague cool-feeling notion that becomes solidified in later sections until you realize it is a major mechanic and theme in the game, like when a minor character appears in an early scene of a book only to be revealed later as a major player in the overall drama. One of my favorite examples of this approach is in the section about striking a bargain to avoid death. The final option is “Bargain with a guardian ghost, if you have one.” Up to this point, there has been no mention of a “guardian ghost” and it is unclear if that is an abstract narrative concept or some mechanical part of play. What?! There are ghosts in this world? Sure enough, three sections later is the heading “Becoming a ghost.” This pattern of set up and reward is of course incredibly tricky, because the unintended result is sometimes just confusing and muddled, with the reader in a frustrated sense of being overwhelmed. There is artistry in the technique, and if you are interested in employing it, I highly recommend that you thoroughly study Poison’d. +Chris Spivey Harlem Unbound has made it to Indy! Woohoo!

2017 RPGs in Review!

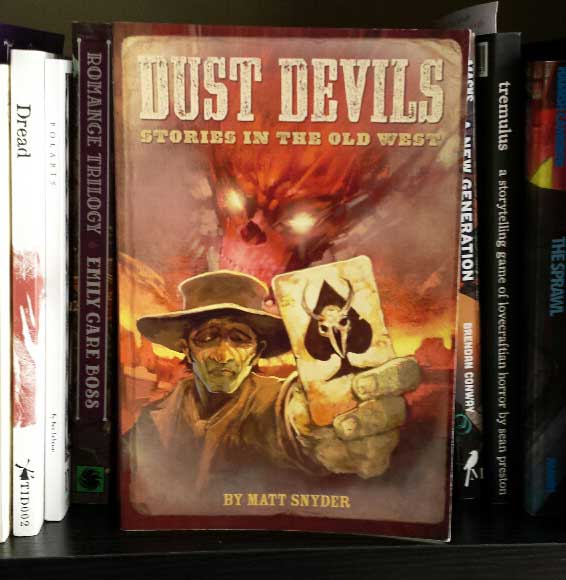

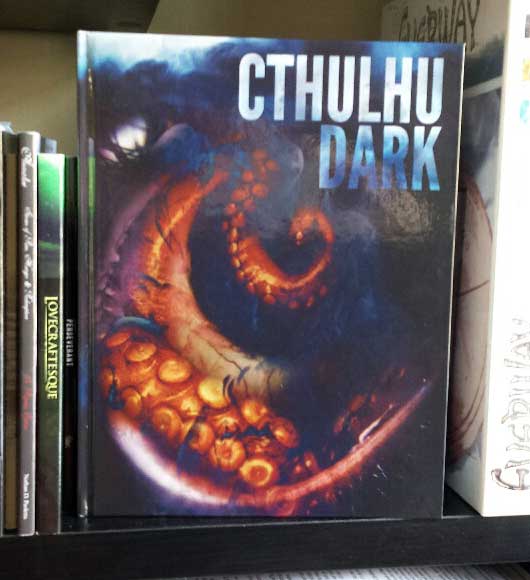

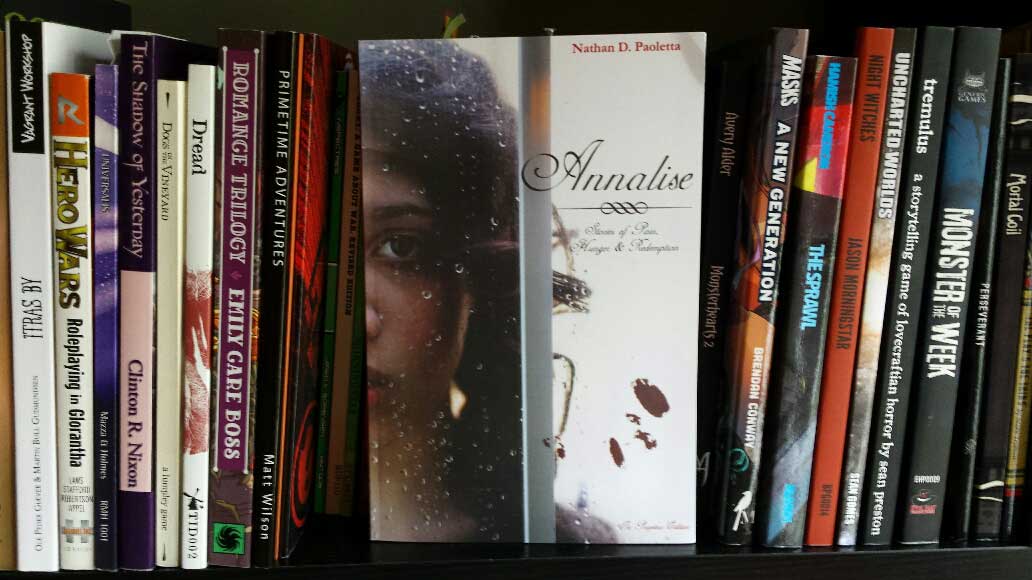

Here’s a list of all the RPGs I played so far this year: Forge of Valor (playtesting - 9 sessions) Monster of the Week (4 sessions) Fiasco (3 sessions) Delta Green (2 sessions) Masks (2 sessions) Call of Cthulhu (2 sessions) Hellfall (playtesting - 2 sessions) My Life with Master (2 sessions) Godsmind (playtesting - 2 sessions) Noirlandia (1 session) Ten Candles (1 session) D&D 5e (1 session) Perseverant (1 session) World Wide Wrestling (1 session) Breaking the Ice (1 session) Restless (1 session) Technoir (1 session) Dialect (1 session) The Quiet Year (1 session) Murderous Ghosts (1 session) I did a lot of reading and studying this year as well. The following list is going to look like a lot, but I didn’t read any of these as they came out and am playing catch-up, so I gave my year over to these texts instead of literary fiction, which is what I have been reading. These are the texts I read and studied: Tremulus Noirlandia Dog in the Vineyard Masks The Mountain Witch InSpectres Orkworld Sorcerer Sorcerer Supplements: Sword, Soul, & Sex Itras By Over the Edge The Shab-al-Hiri Roach Dust Devils My Life with Master Universalis The Shadow of Yesterday Marvel Super Heroes (1984) Amber Diceless Undying Cthulhu Dark Zero 3:16 Carnage among the Stars Primetime Adventures Hillfolk Polaris Annalise Trollbabe And these shorter game texts: Amazons Archipelago Havoc Brigade Hot Guys Making Out In a Wicked Age Lady Blackbird Lover of Jet & Gold Misericord(e) MonkeyDome Risus The Sundered Land Swords without Masters Trial & Terror Wolfspell XXXtreme Street Luge Reading Geoffrey Englestein's collection of gaming essays today and came across this rather innocuous definition of what a game's rules are and do:

"A set of game rules is a logical construction. The rules tell you what you are permitted to do, what you are prohibited from doing, and how the state of the game - scores, locations of pieces, etc. - all change as a result of the players taking an action" (pg. 59 of GameTek) This drove home for me how RPGs are really no different from other games. In RPGs, the fiction is the playspace (the equivalent of the board or cards or whatever - the canvas on which the game is played). The rules tell you how you can legally affect the fiction, and the fiction changes as a result of those actions being made. Okay, now that my last batch of too-good-a-sale-to-pass-up books has arrived, I really and truly am done buying things for myself.

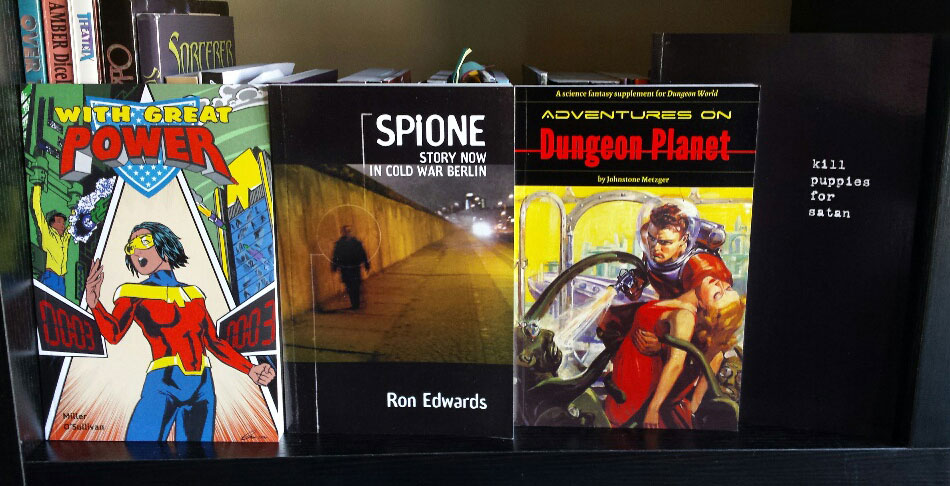

With Great Power, by +Michael Miller Spione, by +Ron Edwards Adventures on Dungeon Planet, by +Johnstone Metzger Kill Puppies for Satan, by +Vincent Baker Really, I'm done. Honestly. First batch of I-shouldn't-be-shopping-for-myself-but-these-sales-are-too-good-to-pass-up RPGs arrived today.

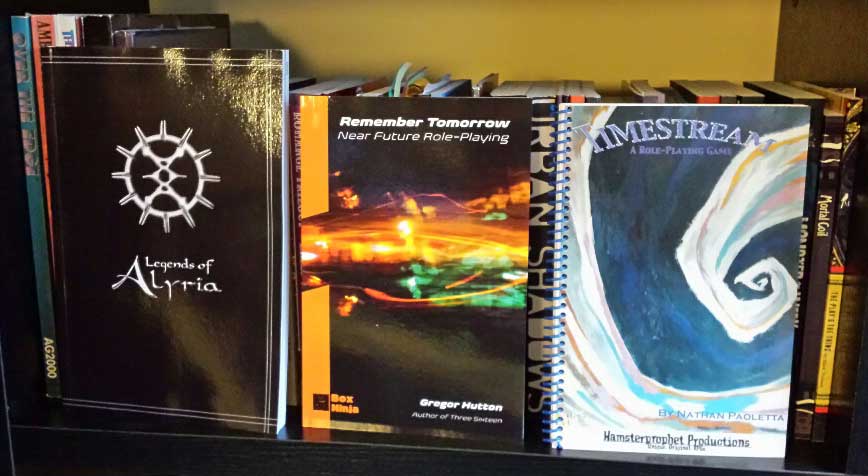

Legends of Alyria, by Seth Ben-Ezra Remember Tomorrow, by Gregor Hutton Timestream, by +Nathan Paoletta So I went crazy on the Lulu.com 40% off sale today and ordered, what, six texts? On the plus side, I spent $85 on $130 worth of RPGs, so I'm feeling pretty good about it.

I got: Vincent Baker's Kill Puppies for Satan Seth Ben-Ezra's Legends of Alyria Gregor Hutton's Remember Tomorrow Ron Edward's Spione Michael Miller's With Great Power And Johnstone Metzger's Adventures on Dungeon Planet Another great mail day! Something old(er), something new!

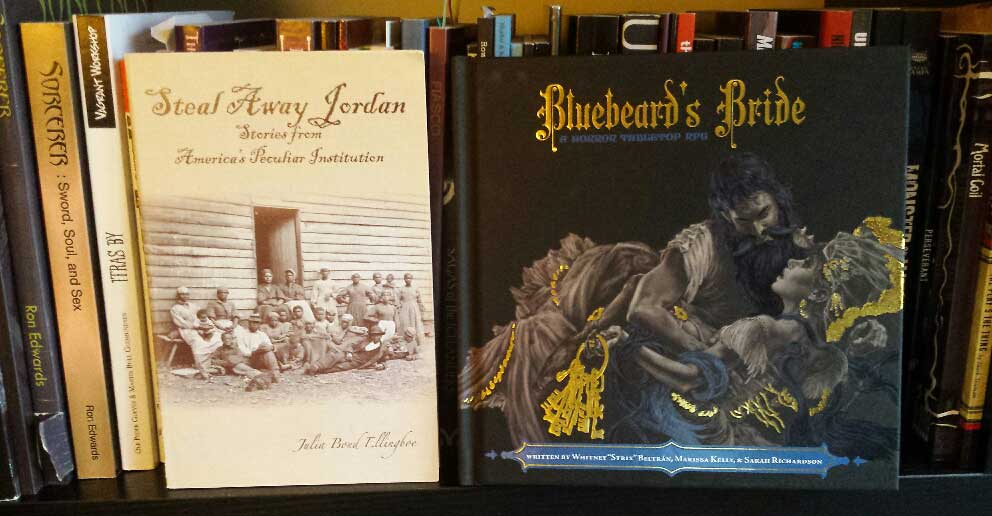

Bluebeard's Bride is every bit as gorgeous as they promised it would be. Here's a podcast about RPG design that you should check out.

+Hannah Shaffer and +Evan Rowland are redesigning Questlandia, and they are inviting us all into the process. Every two weeks they will be talking about what they want to do, how they might do it, and why. Their clever approach is to bring a set of questions for each other to organize the conversation. I listened to episode one last night and really enjoyed just listening to them. Hannah has always been a joy to listen to on the mic, and Evan was eloquent and thoughtful as well--the two, not surprisingly, have great chemistry, resulting in a conversation that is simultaneously professional and intimate. The end result is funny, endearing, thought-provoking, and rather joyful. Check it out on the One Shot Podcast network. http://oneshotpodcast.com/category/podcasts/design-doc/ Thank you to +Nathan Paoletta for making Annalise available in print once again! My PoD copy arrived today and it looks great!

The Storybrewers are back with another fantastic free RPG: "The Ghosts of NPCs Passed."

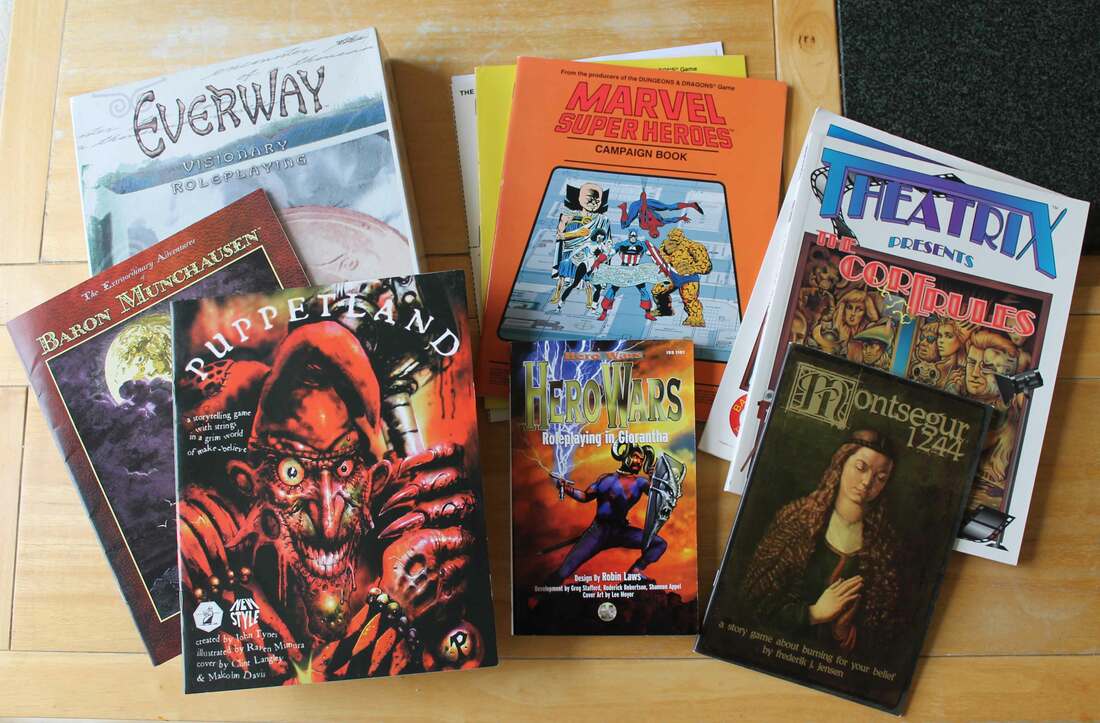

You have left a bloody trail of fallen NPCs in your wake. Hold a seance to let them rise again and tell their untold tales. Download this clever, free, one-page game here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B6jLy2F5sGNzOV9DbGVKSVcwek0/view Been slowly filling in the massive gaps in my education/experience with used RPGs via ebay and Amazon whenever I find one at a great price. Theatrix just came today. The others have come in over the last 3 months or so.

Damn, today was a good mail day.

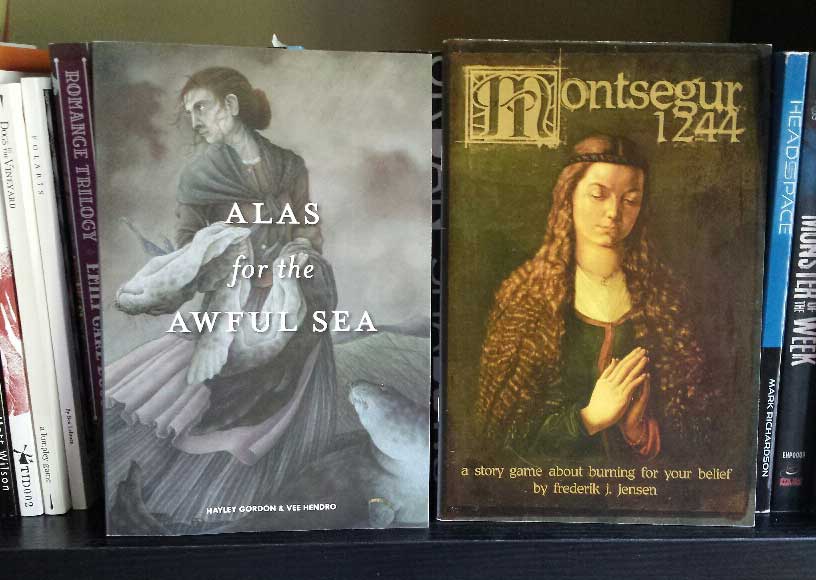

+Hayley G, Alas for the Awful Sea has made it to Indianapolis, and it looks beautiful! “Amber, in the years of play-testing, has been as much a matter of style as any set of specific rules” (page 225 in Amber DRPG)

This is one of the key sentences in the book, I believe. There are plenty of rules to the game, and while the text gives you all those rules, it is especially concerned with communicating the “style” of play that the book proposes. Wujcik’s main tool for showing that style in action are all the examples of play throughout the book. All the procedural rules are followed by script-styled examples of those procedures in play. So what do those examples show us? First, the game plays out it great fictional detail. The GM is constantly asking the players, “what are you doing?” The GM acts as the characters’ five senses and tells them what they detect with their senses and then prompts the players to react. This by itself is very cool thing. A lot of RPGs today strive to ground their game in as much talk about the fiction as possible during the conversation of the game, and it is clearly part of the “style” of Amber to have the game play out this way. So why is it set up that way? What does the game accomplish by adopting this style? I think it is a direct result of being diceless and set in the world of Amber. As Wujcik continually makes clear, the characters are super powerful and can accomplish just about anything with their near-godly powers. Moreover, with defined ranks determining victory, every player could see at a glance who will win any contest just by looking at the numbers. The answer is to obscure those numbers and those facts. Only by keeping the players in a constant state of uncertainty can the GM provide them with suspense, excitement, and mystery. So controlling the flow of information does double duty by first keeping the players in a constant state of uncertainty and by second making the players doubt their ability to do all the things they could easily do otherwise. The control of information is itself a check on the powerfulness of the characters. The uncertainty in the game depends on the players not talking to each other also. Those secrets are kept by pitting the characters against each other. There is a whole section in “How to Play a Character in Amber” called “Keeping Secrets,” in which the players are given half a dozen reasons not to give anything away about their characters. This is part of the reason for the auctioning of attributes. As Wujcik says, “Your job, as auctioneer, is to get those same kind of bitter rivalries going” (225). The GM is told to stoke rivalries during the auction so that the players will put that rivalry into their characters. I think most of us can agree that that is a messed up way to run a game, but messed up or not, that is the way the game is structured to operate. Hell, secrets go so far that even players are kept in the dark about their characters during advancements. GMs are told not to tell players how many points they earn for advancement. The players have to make wish lists in prioritized orders and let the GM assign the points according to that wish list. An RPG I would like to play:

A world in which Asimov's Laws of Robotics are in place--and I would like the players to play the robots, bound by those laws. What would that look like? What would the characters do? How would being subject to the whims of NPC humans throw wrenches in the works? Step 1. Compare the Attribute Ranks of the participants in any Combat.

Step 2. The character with the larger Attribute Rank wins (page 80 in Amber DRPG). Sounds simple and straightforward. Then the game goes on to undermine that basic 2-step process. As Wujcik says in the section on “Campaign Advancement”: Points, desirable as they may be, do not an Amberite make. After all, it’s not a character’s Attributes, Powers, and items that determine superiority. It is how they are used. Pit a skilled and experienced Amber player, with a 100 point character, against a raw beginner with 200 points, and the outcome is certain. To paraphrase an old adage, quite appropriate for Amber, ‘age and treachery beat youth and power every time’ (139). By the basic rules of the game, a 200 point character played by anyone should beat a 100 point character played by anyone else because the “character with the larger Attribute Rank wins.” But that is of course not the case, so there is another resource available to the players that determine their success other than their points. In a diceless RPG, the players depend on resources of some sort to affect any encounter’s or challenge’s outcome, otherwise there’d be no mystery in how the game unfolds. At a casual glance, the resource in Amber are the 100 points that each player begins the game with to make their characters. You allocate those points to decide where your character will succeed and where they will struggle. But there must be another resource if the above statement is to be believed. The combat section of the text is really good. There are a lot of play examples and the text gives the players a lot of language to talk about a sword fight, even if you don’t know a thing about sword fighting except for what you’ve seen in movies. The text breaks your stances as a fighter into 1) attacking furiously, 2) taking an opportunistic stance, and 3) going defensive. Then each of those stances if broken down into more detail, and the text indicates how each stance will affect the battle depending on whether you are much better, a little better, the same, a little worse, or much worse than your opponent. But of course, you never know how you compare to your opponent because the GM is never up front about that point, so your success in the battle will depend on which stances you take to suss out your opponent and then what stances you adopt by what you learn early in the combat. When I first read this section, I made a note about how useful the language was. When I finished the book, I realized how critical that language is to the game because the language becomes coded within the context of the game. The GM is prompted to interpret the language used by the players in judging the success or failure of their actions. How well a player masters that language has a direct impact on how well their character does within the game, according to the whole of the rulebook. That language, that is the hidden resource available to the player. The other way to look at it is that the GM is the hidden resource, and the experienced player knows how to tap into the GM’s unspoken expectations. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed