|

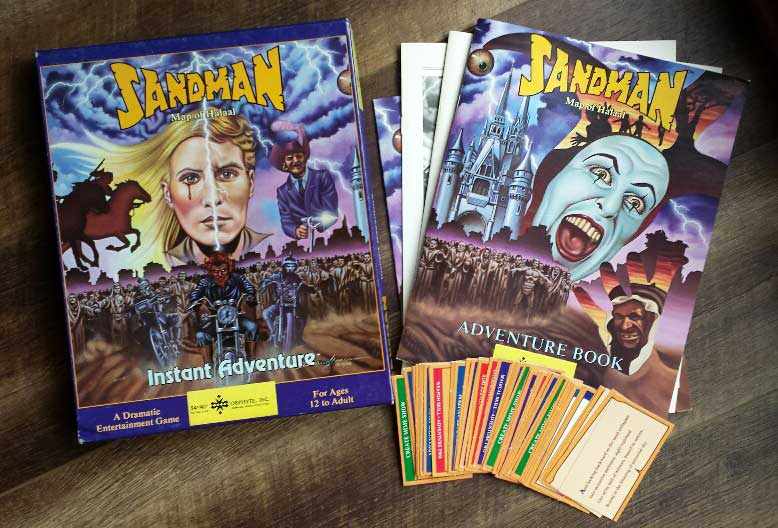

Next on my reading list: Sandman: Map of Halaal

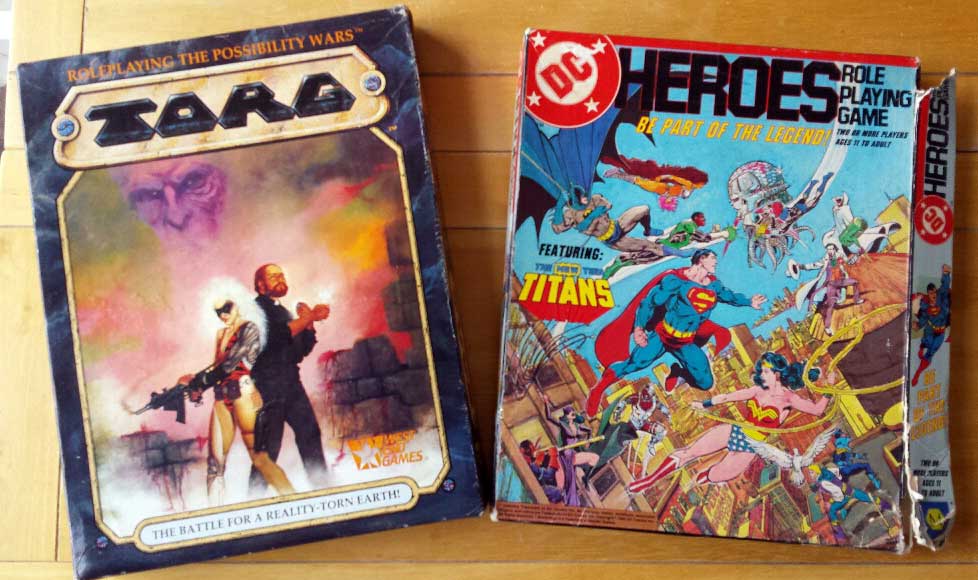

James Wallis referenced this game in one of the RPG questionnaires that circulates around the interwebs as a game that has had a lasting influence on his game design. Jason Morningstar commented that the game had an impact on him as well. Shortly after that conversation, I read about the game in Shannon Appelcline's Designers & Dragons: the '80s and was intrigued by the idea of the game. So I found a cheap copy on ebay and ordered it up. Anyone out there ever play it? Thoughts? Impressions? I'll tell you mine when I'm done reading.

0 Comments

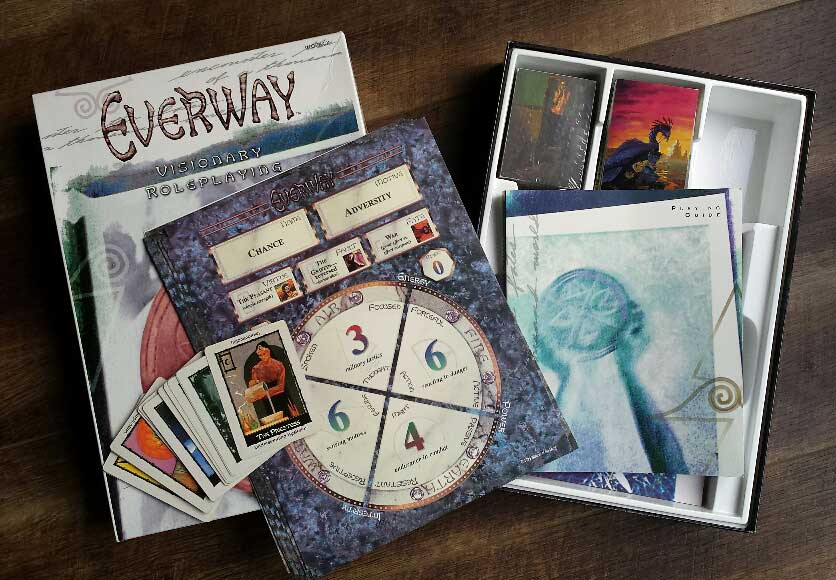

I’ve had a lot of fun reading and thinking about Jonathan Tweet’s 1995 RPG Everway.

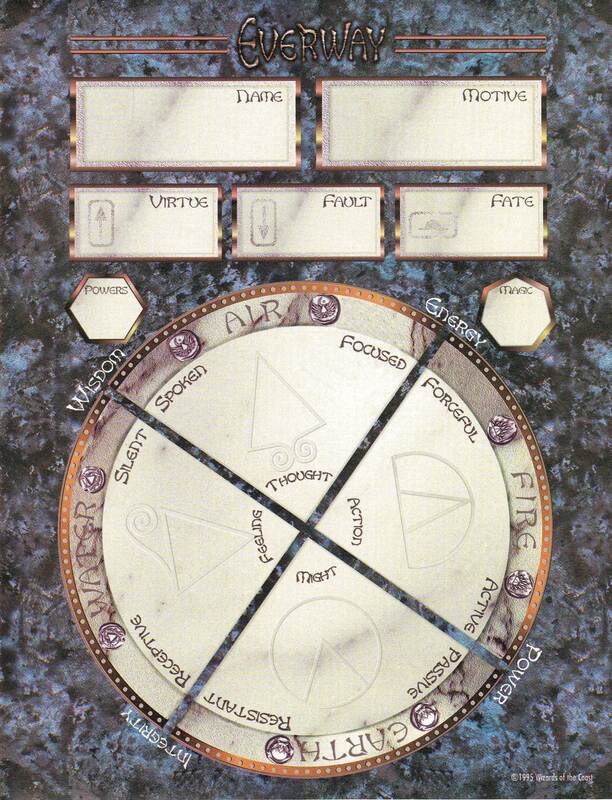

I knew going into it that the game used a “Fortune Deck” and a set of “Vision Cards” in some way, and I knew that Tweet, at some point in the text, makes the distinction between 3 approaches to resolution: karma, drama, and fortune. That’s the sum total of what I knew when I dove in. The game box includes three 7” x 8.5” books: a 160-page “Playing Guide,” a 14-page “Guide to the Fortune Deck,” and a 64-page “Gamemastering Guide.” You are instructed to start with the “Playing Guide,” to which both character players and GMs are openly invited. A little over the first third of the book is devoted to establishing the setting, a fantasy multiverse of worlds that the players can travel between via “gates.” The game itself is named after the main city in the main realm in the main sphere. Play is designed to create episodic and epic narratives as the PCs move through the spheres (spherewalking, as it’s called) solving problems and getting tangled up in local customs, mysteries, and what-have-yous. The next chunk of the “Playing Guide” (again, over a third of the text) is dedicated to character creation. Character creation in the game is really cool, using the “Vision Cards” to inspire players. The vision cards are regularly-sized cards with images of characters, situations, locations, scenes, and mythical creatures. They are beautiful and mysterious, working to suggest things but leaving a lot unanswered and only hinted at. The game comes with 90 of these cards, and there were two expansion sets of 90 more cards each produced before the game line was canceled. You spread out these cards on the table, and the players pick five cards to serve as inspiration for their characters. The cards might represent the character herself, someone important to her, where she comes from, the scene of some pivotal moment in her life – whatever the cards inspire. It’s a really cool way to begin character creation because the pictures can push you in directions you would not think to go, and the pictures in conjunction with each other can only drive you further in unexpected and interesting directions. And because all the cards are thematically appropriate to the tone and subject matter of the game, every character derived from the pictures will be well suited to the same universe. I also appreciate that the designers were thoughtful in their representations so the cards have people of every skin color represented, and most cultural depictions are non-Eurocentric. After selecting 5 cards as the inspiration for your character, the players share the cards and explain what they have drawn from them. Then players are invited to ask each other questions about the cards and the character being developed from them. This is the first game I know of (although my pool of knowledge is admittedly shallow) that has questions from other players as an explicit part of character creation. It feels like very modern tech, and I love it. The “Fortune Deck” is also used in character creation. The Fortune Deck is a deck of 36 cards, modeled on the major arcana of tarot decks. Each card has a regular “meaning” and a reversed “meaning” when played upside down. I put meaning in quotes because the printed meaning is hardly definitive. Like everything else in the game, the cards are suggestive and up for interpretation. For example, the Autumn card means “plenty” and reversed it means “want,” but what plenty and want mean can range through a great number of possibilities. In character creation, the players go through the cards of the Fortune Deck and pick one card to represent the character’s Virtue or strength, another to represent her Fault or weakness, and another to represent the character’s Fate. For the Virtue and Fault, you pick one meaning from the card, but for the Fate, you consider both meanings to create a set of poles for your character, the two possible paths you see before the character. For example, if you select The Fool, your two poles would be “freedom” on the one hand and “lack of connection” on the other. That could mean whatever you want, or you might not know exactly what that means at all but it feels right. Your character is forging her own path but runs the risk of isolating herself as she does so. What’s cool about all of these elements of character creation is that they are about how you as a player want to play your character. Who they are, what motivates them, where they are going, and where they have been. Moreover, each element potentially adds to the depth and complexity of your character and has the opportunity to push you into a direction you hadn’t considered, making the character’s starting form somewhat surprising to you as a player, which I find very attractive. The game uses the four elements to structure the characters’ stats: air, fire, earth, wind. That alone sounds clever but uninspired, but the execution of the stats is really well done. The real accomplishment is the presentation of the stats on the character sheet. Here’s how the book defines each of the stats: “Fire measures vitality, force, courage, speed and daring.” “Earth governs a hero’s health, endurance, fortitude, will, determination and resilience.” “Air determines intelligence, speech, thought, logic, analytical ability, oratory, and knowledge.” “Water governs intuition, sensitivity to that which is unseen and unspoken, receptivity, psychic potential, and depth of feeling.” All of those are reasonable categories. I’ve included a scan of the character sheet so you can see how the stats are mapped out there. You can see that each element is presented as a quarter slice of the pie. At the point of the slice is a one word summary of the element: Action, Might, Feeling, and Thought. Then each slice is joined to its neighbor by a commonality. Air and fire are both about energy, but air is a focused energy and fire is a forceful energy. Both fire and earth are about power, but fire is an active power and earth is a passive power. Earth and water are both about integrity, but earth is a resistant integrity and water is a receptive integrity. Finally, both water and air are about wisdom, but water is about silent wisdom while air is about spoken wisdom. This map defines all the corners of each element and does a great job of defining at a glance what each element covers during play. The problem with abstract concepts for stats is that they are work for players to remember during play, but the character sheet allows the designers to keep the flavor of the elemental division while removing the burden of memory from the players. For me, the visual design of the character sheet is as important as the conceptual design of the statistics. I’ve already rambled on too long, so I’ll skip discussing magic and powers for now. The reason I’ve spent so long on the character creation is because character creation and the resulting character and sheet are one half of the game in play. Everything the players need to play the game is there on their character sheet, and a great deal of what the GM needs to run the game is there on the character sheet as well. After covering the setting and detailing character creation, the rest of the “Playing Guide” and the entirety of the other two books are really about running the game as GM, but there aren’t really any “rules” to speak off. The system of play for Everway is entirely reliant upon the GM. The players say what their characters do and the GM determines the results of that reaction. That is the entirety of play in a single sentence. So what the remaining 80 or so pages of text are about teaching the GM how to make those decisions fairly, dramatically, and creatively. I expected the discussion of karma, drama, and fortune to effectively be a short essay within the text, but it’s really so much more than that. What Tweet does in the text is effectively attempt to breakdown what GMs do when answering the question what happens next? Sometimes the GM just decides that the action is a failure or a success. They look at the character sheet and decide that the character is or isn’t strong enough, magical enough, talented enough, or whatever to do the thing they want to do. Or the GM looks at the fictional positioning and decides that the character’s approach or tactic is likely to be effective or not. After evaluating the measurable facts of the situation, the GM declares success or failure. That whole process is called “karma” by Tweet. Sometimes the GM decides that it would be dramatically exciting if a character fails or succeeds or that things go sideways instead. Sometimes the GM decides that the character can’t get what she wants because it would short circuit the entire mystery or defuse the entire situation too readily. That decision process is called “drama” by Tweet. The dramatic ruling is based entirely on matters of the story and has nothing to do with what is likely or what a character is capable of. Finally, the GM sometime leaves the results of an action up to fate and employs some kind of randomizer, dice, cards or whatnot. That’s what Tweet calls “Fortune.” In the case of Everway, the GM can draw the top card from the Fortune Deck and interpret it as a favorable sign or an ill omen. The rules are very explicit that all of these ways of making decisions will overlap and occur concurrently. There is also a matter of taste, some GMs preferring to decide things by karma, others preferring to leave things to fortune, and still others constantly thinking of the dramatic impact of the actions on the story. But whatever your leaning as a GM, you draw on all three methods constantly. I found the analysis compelling and the breakdown impressive. The text is really an extensive guide to how to make decisions as a GM with a particular focus of how to GM this game. The guide teaches you how to interpret the statistics to determine likelihood of success, how to look at the prongs of the story to determine what is up for grabs and what needs to happen without interference, how to read the fortune cards to determine if they bode ill or well, all in an effort to teach the GM to be a fair and impartial judge of the character’s actions and the ramifications that follow. I of course had problems with plenty of the particulars. The discussion surrounding reading the outcome of a sample fight reminded me of nothing so much as Erick Wujcik’s Amber. In both game texts, the game wanted to use the numbers to determine outcome while still allowing for surprise and unexpected outcome, leading to a coy game between players and GM as the GM determines what course of action will be especially effective and the player tries to meet the GM’s determination. In the end, such play measures success by one player’s ability to read the mind of another, which is a pretty shitty system. And the idea that a GM will undermine a clever player by refusing to validate a character’s action because the GM is committed to a particular plot is offensive to modern RPG sensibilities. But these problems I had didn’t impact my ability to appreciate the crux of Tweet’s analysis. There’s nothing about the system itself that helps the players have an interesting and compelling game, since the system is the GM. There are no mechanics to propel play or story, nothing other than a set of resolution tactics, so I imagine that play is exactly as interesting as the skill of the players involved. With an inspired GM and lively players, I can see some very fun games coming from play, but there is nothing to keep the game from being ho-hum or even downright dull if the players and GM are unsure of themselves because there is nothing mechanical within the game to catch them and support them. The closest the game comes to providing a means to keep things lively is the Fortune Deck as a surprising tool for resolutions, and I do love the possibilities it holds. I was surprised to find that there is no XP or advancement system in Everway, especially since the game was designed with campaign play in mind.

What pre-1995 RPGs can you think of that were designed for multi-session play but that did not have any kind of XP or advancement system? The curious want to know! ETA: Maybe instead of advancement system I should say improvement system, by which I mean, there is no mechanical way for the characters' numbers or abilities to change. The characters can acquire stuff with magical properties through play, but they cannot themselves improve. Here's what I'm currently reading/studying: Everway.

Have you played? Tell me about your characters, your adventures, your experiences with the system, what blew you away, what troubled you, etc. And Gen Con is done!

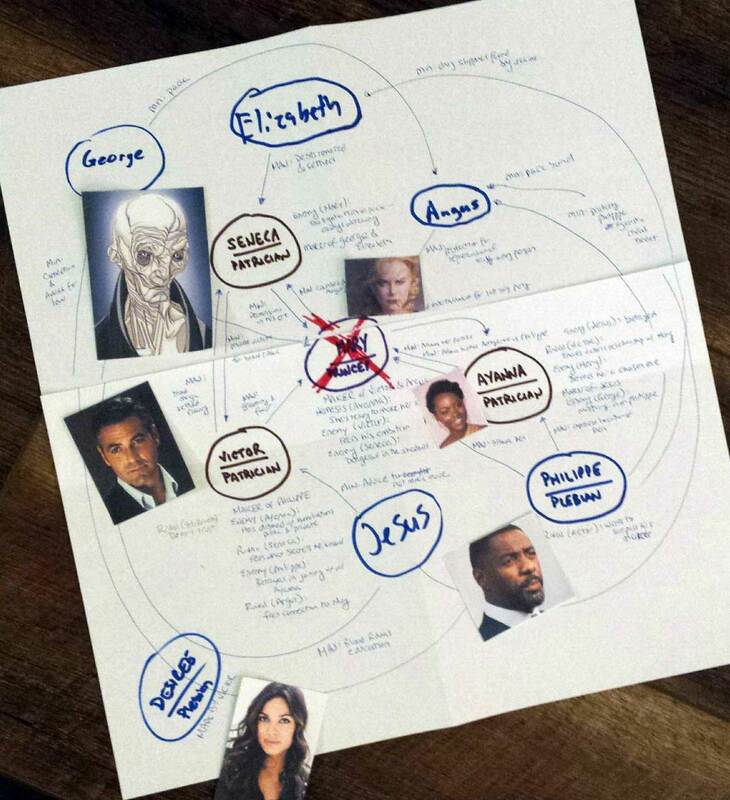

Thankfully Ann was feeling better by Friday afternoon, so after dinner we played in two Games on Demand events, from 8:00 -10:00 and 10:00 - midnight. We played Ross Cowman's BFF with Ross himself and 3 delightful strangers. It's a lovely game, with beautiful art, neither of which was a surprise. We also played The Final Girl, which the GM/facilitator billed as "Murder Party," in which we would create a D-grade horror film. It was a rough gaming experience for us since our own personal styles and tastes were at odds with the other players at the table, but what can you do? It was only two-hours, and it gave us a lot to talk about and analyze on the trip home. Gaming style is one of those things I'm not aware of until it is contrasted with someone else's. Saturday morning I GM'd my first con game, Paul Riddle's excellent Undying. My only point of anxiety was that the game was set in London in 1940 during the blitz, and I wasn't familiar enough with the city to have ideas for hunting grounds on hand or good detailed descriptions of scene locations. I ended up looking at a lot of maps and reading up on neighborhoods, printing out pictures of war-torn London and other details so we could all be on the same descriptive page. The game went pretty much perfectly. The players were all in great creative shape and they leaned into their playbooks' status moves, trying to navigate the political landscape to come out on top. We had our climactic scene in the dead princep's lair with a 50+ blood-token-fueled blood ritual that brought her desiccated corpse back from the dead/undead to take vengeance on her killer. Three of the four players managed to trigger their status moves to become patricians, but it was clearly going to be a tense situation between them and the existing power structure. The fourth character had clearly backed the wrong horse, but not so openly that his fate was sealed. He would take a setback but be alive to fight another day. It was an exciting ending that suggested all kinds of possibilities for future play, and everyone left wanting more. I couldn't ask for anything more. (The picture is of the R-map from this game.) Saturday afternoon was spent playing games with our son and partaking in an MtG chaos draft (in which you are given three random packs taken from sets from the last 5 years or so ). Ann won it, so Orie was delighted to turn those prize winnings into more packs for drafting at our local game store next Friday. This morning was my second game of Undying, and it was . . . fine. Three players showed up, which for a Sunday morning is a pretty good win. The scenario was called "Undying: The Awakening" (set in Chicago during the World's Fair in 1893), and one woman thought she had signed up for Mage: The Awakening. Whoops. She decided to play, but her enthusiasm was certainly muted. Once play got underway, it was clear that two of the players did not like each others' style, but they forged on uncomplainingly. None of the players really leaned into their status moves, and I think my construction of the conflict didn't give them enough of a third side to maneuver to, all of which resulted in the play being rather reactive, responding to NPCs more than purusing anything proactively. We still managed to have an exciting climactic scene with shotguns to faces and near-deaths. All three said they enjoyed themselves, and I believe that was mostly true. I can say with confidence that none of them had a bad time? I think? I hit the dealer's floor one last time to pick up a couple of items my son planned on getting (but he was too tired this morning to join me), and then dragged my exhausted ass home. It was a great weekend. I'm really looking forward to sleeping tonight. As one who calls Indianapolis home, I want to welcome those of you who came here for Gen Con! Enjoy our wonderful city, even if only for a quick romp around the circle, and have an awesome time gaming for the next half-week.

I'll be RPing right alongside you, and I'll even be GMing my first games at a con--two games of Undying, which I'm pretty psyched about. See you there, you fantastic people! Day 1 of Gen Con is in the bag for me. Sadly, my wife was feeling poorly, so we didn't get a chance to play any games today. She is better now, but we'll take tomorrow slowly and see how it goes.

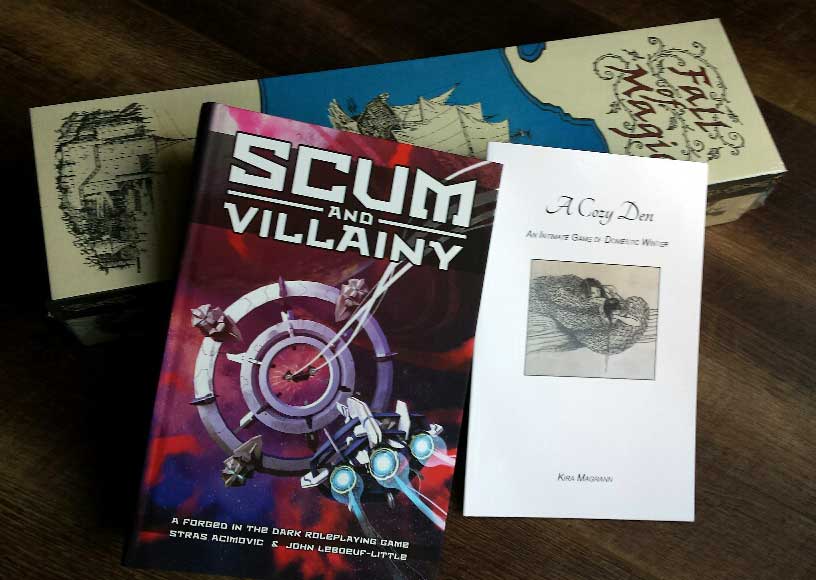

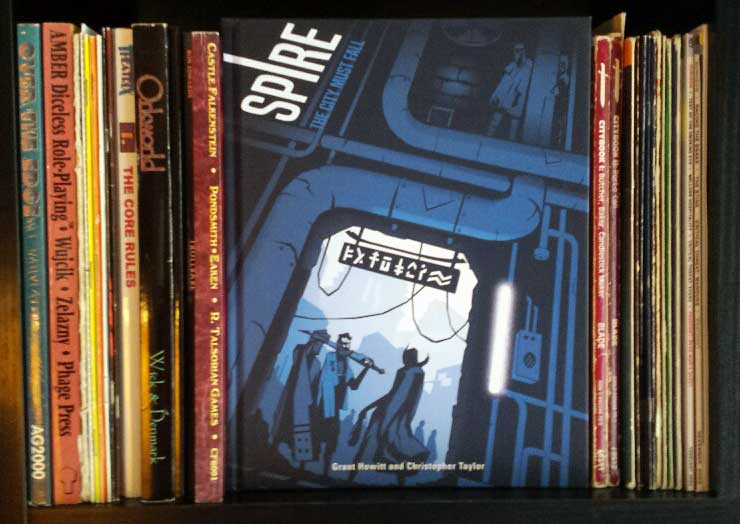

Our son had a hilarious story to share from his time in the playtest room for early-in-development games. He loves playtesting and was excited to get to do it again. He couldn't get into the game he wanted to test, so he picked one at random that described itself as a game about gangster wars on the streets of a Chicago-like town, full of violence and lawlessness and greed. "Oh no, was it too violent and lawless and greedy?" I asked "Dad. It turned out to be a Monopoly knockoff." "What?! Why would anyone re-tool Monopoly?!" "Oh yeah. You had criminal ventures instead of properties, like money laundering. Then, when you past go, you got two gangmembers, which you could send to battle other players gangmembers to take their properties. At that point, it was like Risk. "What?! Why would anyone take Monopoly and mash it up with Risk-style battles?!" "Oh yeah. You rolled 6 dice every time you attacked, no matter how many gangmembers you had, and the defender rolled 5 no matter how many gangmembers they had. Whichever side has the least number of gangmembers, that's how many dice both sides keep. So if your 5 guys attacked their 1 guy, you rolled 6 dice, they roll 5, you each keep the highest die, and ties go to the defender. So her 1 guy can destroy all 5 of yours pretty easily." "That's horrible!" "Oh yeah. We were all trying to get into fights as soon as we got gangmembers so they would die off. It was against the rules to attack a player if they had no gangmembers. So 6 of us were killing off our own guys as quickly as possible, and the last 2 were trying to duke it out." I was laughing out loud in the food court. "Oh, and the chance-card-things? Yeah, 'Drive by: roll a dice and lose that many gangmembers and that many turns.'" "What?! You could lose 6 turns on a die roll?!" "Oh yeah. That happened to one of the players, and the designer said, 'don't worry, they go by fast.' But with 8 players, that's 48 turns before you can do anything!" "The designer was running the game? Did he take feedback?" "'Take' it? Well, we gave it, but he swatted it all away. One guy said, 'there's a problem with the combat.' the designer said, 'No, there isn't.' It was ugly, and I hated it." But we were both laughing pretty hard by that point. His story might have been my favorite part of the con today, except for the game of Mars Colony that my wife and I started at lunch. Oh, and I did all my shopping today. I had a short list, as you can see in the picture. I hope you all had a great day today too. The only problem with reading +Shannon Appelcline's wonderful Designers & Dragons series is that I find myself scanning ebay listings for great buys on games I didn't know I wanted to read.

I've been mostly good, but there were a few moments when the opportunity was too good to say no to. Just had one of those magical sessions where everyone at the table had a moment that surprised the rest of us and defined their character in an unexpected and solid way. Everyone was contributing first rate ideas and fiction, and at the close of session, it felt like a superbly written drama.

Better yet, my wife and I got to take a long walk around the neighborhood afterwards and break down all the places skill and good fortune came together to give us something better than we could have hoped for. I love the peaceful exhilaration that follow such a session. So there are a ton of great Kickstarter's going on right now, and while I've been backing, I haven't been sharing. Anyone connected to me here on G+ is probably already connected to others who have backed and promoted these games, so you probably don't need this in your feed. But just in case I am the only one, or in case I can be the tipping point that moves you to back one of these games, this is what I'm supporting at the moment.

1) Dream Askew // Dream Apart: Only 12 days to go. You don't want to miss it. Oh, and listen to Benjamin Rosenbaum on the latest +1 Forward podcast to hear what a cool game Dream Apart sounds like. https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/averyalder/dream-askew-dream-apart 2) Champions Now This is +Ron Edwards' re-imagining of the original Champions game from 1981. The updates are full of short videos of Ron explaining what he's doing in his design. Champions was the first RPG I paid for with my own money in 1982, at the tender age of 10, so there is some sentimental attraction for me here. Whether you're in it for the game or the insight into game design, this should be a fun project to follow. https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/herogames/champions-now 3) The Mountain Witch This has been a long-time coming, and it's finally here! I have never played the game, but you cannot read anything about indie RPG design from the early 2000s and not understand that this game is a major touchstone for the games coming out of the Forge community. I have read the original text and am excited to see where the game has grown and where it has stayed the same. https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/timfire/the-mountain-witch-samurai-blood-opera-in-mythical 4) The Black Hack, 2nd edition This is one of those influential games that I am signed up for because 1) it is widely referenced, 2) it is praised by designers I respect, 3) it is very cheap at the PDF level ($7 US). https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1730454032/the-black-hack-rpg-second-edition 5) Gather, Children of the Evertree This is +Stephen Dewey's latest offering: a no-prep, GMless/GMful, card-based, diceless RPG/talking Larp about communities meeting in a heavily ritualized gathering. It sounds fantastic. Listen to the latest 3W6 podcast to hear an interview with Stephen about the game. https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/shiftyginger/gather-children-of-the-evertree An excellent mail day! Two Kickstarter rewards: +Todd Nicholas's The Sword, The Crown & the Unspeakable Power and +Ben Dutter's Vagabonds of Dyfed. Both are beautiful-looking books!

The Burning Wheel is the only rulebook I've read with a rule for what to do if PCs want to buy something in bulk. That's . . . fun.

I've been going over +Vincent Baker's Mobile Frame Zero: Firebrands, and I was bummed I couldn't find any printed books. So I decided that with my PDF, a sheet of cardstock, 8 sheets of paper, some clever printing of the PDF, a paper cutter, plus needle and thread, I could create my own printed book. So I did. It looks awesome. It took about a half hour. I think I'll wait until I've scheduled a game before I create any more, though.

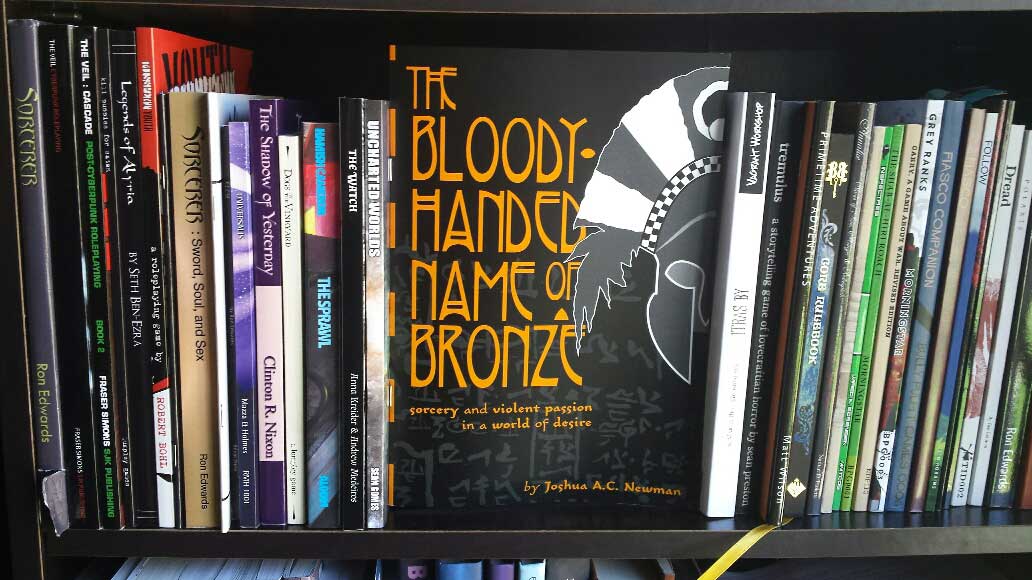

Also! +Joshua A.C. Newman's Bloody-Handed name of Bronze is in the house. Or, at least it's in my house. Good day on the RPG front. "We're so pleased to be able to announce More Seats at the Table - an email newsletter designed to highlight games made by designers and creators who don't fit neatly into the gender binary, femmes, and women.

"More Seats at the Table came about as a result of a conversation between Kira Magrann and Anna Kreider about the problem of games by and about not-cismen being perceived as only for not-cismen - and they decided a good way to address this challenge would be an email newsletter highlighting the work of marginalized designers. To that end, they enlisted the organizational aid of Misha Bushyager of New Agenda Publishing and Kimberley Lam. "But we don't just want this email list to be subscribed to by marginalized designers. Cismen, we'd very much like you to subscribe, and if you find work that excites you - then we hope you'll consider either buying or using your platform to signal boost work by marginalized designers that you find exciting!" Follow the link and fill out the form to get on the mailing list. Hell, the first issue is being mailed out this Friday. While you're there, if you have the means, throw some money their way by pledging their Patreon. My review of Gregor Hutton's Remember Tomorrow:

Gregor Hutton’s Remember Tomorrow packs a lot of game into a small book. My copy is a mere 48 pages long, and there are plenty of pictures and tables and reference charts, making the whole book a quick read. And what you get for that quick read is a lot of cool mechanics that give you the tools to create a near-future cyberpunk story without any preplanning or long-term commitments. I keep looking for the place where the game cuts corners, but I can’t find any such place. Let me make clear that I haven’t played the game, only read it. The game runs without a dedicated GM. Instead, the players take turns creating scenes for the characters, and during your turn you can create one of three types of scenes. In the first type of scene, you can introduce a new PC or a new faction. Each player is responsible for a “held” PC, meaning you and you alone can play that character and drive that character to reach her goal. In addition to held PCs, players can make up additional PCs to be played by anyone in any given scene. Opposing all the PCs are various factions: organization or individuals who are trying to grow their influence in the area, who have debts to settle and favors to grant. Factions are never held, only shared. In the second type of scene, you narrate or roleplay your held PC making a deal with a faction. Your character gets to improve her situation and the faction increases its influence. In the third type of scene, you play a faction or a non-held PC trying to hurt or set back another PC. Round and round the table it goes, each player creating a new scene and playing them out. Each character has three stats, called parameters: Ready, Willing, and Able. In addition to those stats, each PC has a motivation and a goal that they need to be ready, willing, and able to achieve. Through gameplay, the players attempt to gain successes for each of the three stats. When the third stat is ticked, the goal is accomplished. When a PC is opposed by factions and other PCs, they can have those tick marks erased, making the players not ready, unwilling, or unable to achieve their goal. If you achieve your goal, the PC is “written out” of the narrative. The player of that PC can pick up the non-held PCs and factions as play continues. The other way to get written out is if one of the character’s stats is reduced to zero. Factions don’t have R/W/A stats. Instead, they have a single stat called Influence. If a faction’s influence is reduced to zero, or if it is increased enough, the faction can be written out of play as well. The game ends after the third PC or faction is written out of play. If you get too kill happy, then the game might end before your character achieves her goal, so you have an interest in keeping the characters well enough to let you be one of the three written out characters to end the game. For all the simplicity of play, there are a lot of cool elements to the game. While the character sheets are lean, there is plenty of heft to them to guide your roleplaying. The three tags of Identity, Motivation, and Goal go a long way to giving you a focused character, and the three parameters of ready, willing, and able, neatly define what your character is all about. The other thing on your character sheet is a list of positive and negative “Conditions.” Conditions walk a really cool line between fictional descriptors and currency, as you can remove positive conditions in order to give yourself an additional die before you roll, to allow yourself to reroll all your dice after a roll, or to increase your gains during a success. Negative conditions on your character sheet can be erased by opponents in order to lessen the measure of your victory when you win an opposed roll. You then, of course, have to work those details into the fiction, but doing so looks to be not difficult in the least. Factions are a cool tool to join the PCs’ disparate stories together as you work with one faction and against another in intended or unintended opposition to the other players. It looks to create a dynamic set of relationships rife with excellent drama. Edge dice are dice you earn if you win a conflict against another player while you are playing a non-held PC or a faction during a Face Off scene. Edge dice are extra dice that you can add to any roll you make, giving your character that much better a chance of success. It’s a neat reward system to encourage players to embrace the oppositional factions and make life hard for the other players. Oh, and doubles and triples rolled cause “Crosses” to occur, which means that the next scene mush include some element or ramification from the current scene. Not only is it clever to have double and triple crosses be a thing (and it is clever), but it’s a really cool way to further ensure that the PCs' stories overlap and interact. It blows my mind because it is so simple, creates no extra work or burden on the player, and it’s a fun thing to do with something that is naturally exciting (rolling doubles and triples) anyway. The concept of characters and factions being “written out” seems like an awesome tool too. It not only builds in an end point, but it allows for a number of stories to come to a conclusion (tragic or triumphant) while leaving a handful or threads unaddressed. In short, it creates something tidy enough to provide some closure to the narratives and messy enough to leave things to wonder about, and there is something incredibly attractive to me about that. Other than Remember Tomorrow, the only book of Hutton’s that I have read is 3:16. From those two works, I can tell you Hutton is a fantastic writer. There is a ton of voice and flavor, but in a way that never interferes with the instructive nature of the text. The writing itself is setting and inspiration, aligning the reader with the types of stories the game is designed to tell. The tables and charts are evocative and productive without ever being dense or difficult to navigate. The lists all come in sets of 10, so if you don’t want to just pick an item from the list, you can roll for it. There is also a motif of words joined together by slashes (winner/loser, characters/factions, name/handle ,etc.) that runs throughout the book that is surprisingly cool and effective in creating a unifying look and feel. My I-only-read-it review of +Vincent Baker's Mobile Frame Zero: Firebrands:

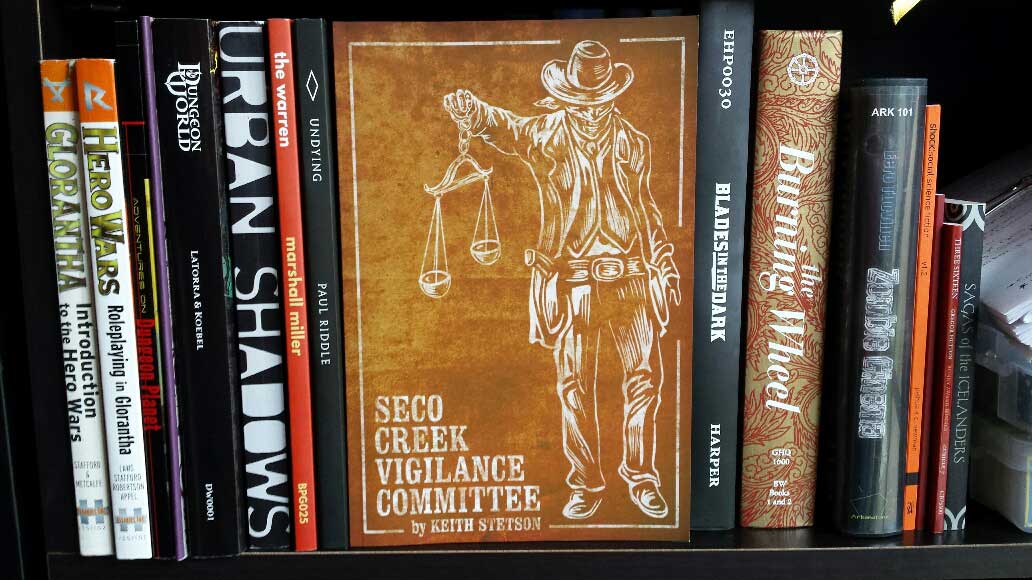

In many ways, Mobile Frame Zero: Firebrands is a typical GMless/GMful RPG. Each player controls a single character. Play proceeds in an orderly fashion around the table, each player calling for and creating a single scene to be played out during their turn. There is no prep—conflicts and tension are built at the table through play and discussion. All pretty standard stuff by now. But everything about the way that scenes and play are structured is unlike those other games. If you’ve played or read other RPGs by Vincent and Meguey, then you are familiar with their preference for guiding play through lists and options that are simultaneously restricted and open ended. Firebrands uses that same technology to great effect. As usual, let me clarify that I have not played the game, only read it. There is very little established setting for the game, but it gives you everything you need for rich situations. Characters play romantic ace pilots of battle mechs on a planet going through a great deal of unrest. The planet of Bantral was colonized long ago, but it had never been worth anything. Lately, one of its natural resources has been discovered to be profitable, so the various powers and people involved are wrangling for control. There are three basic sides in the conflict: the offworld moneyed interests who “own” large chunks of the land; the long-term colonial occupiers who are essentially nobility on the planet, having lived there for generations; and the native inhabitants who have been occupied and work under the colonial nobility. Each player’s character is aligned with one of these three factions, and all three factions need to be represented in the game. But Firebrands is not a game of war. If war breaks out, big government bodies will get involved, so everything is kept at the level of manipulations and skirmishes. The game focuses on the interactions, social and romantic, between the PCs as they meet on the battleground and at social functions. What are you playing to find out? “The object of the game is to create messy entanglements. Fall in love with your enemies, ally with your rivals, fight with your friends” (3). As a player you need to embrace the messiness and gleefully maneuver your pilots into these sticky situations. How does the game help you do that? Scenes are set up as a series of “games,” but you can think of them as specific types of scenes. There is a solitaire game that gives you a fictional situation that your character has recently engaged in (you pick from a list, of course) and pick what the general outcome of that situation was. Everyone begins by playing a game of solitaire, but you are free to play it whenever you like; for example, during someone else’s scene that doesn’t involve you at all. Whenever you play, you do not tell others what happened. Instead, at the beginning of all the other games, you are prompted to tell the other players what they “notice” about your character or what rumors they may have heard about your character. That’s how you bring this background material into the shared fiction developing at the table. It’s a cool way to allow players to find whatever messy background material they need to help them determine how to interact with the other factions during the other scenes. So here are the games and scenes you create with others during play: you can engage in an animated disagreement with one other player’s character, an argument that is moderated by the non-participating players; you can have a chase of one character by another, in or out of their mechs (called “mobile frames”); you can have a casual conversation over a meal with another character, focusing more on the social give and take of the conversation rather than the substance of the topic; you can share a dance with another character to explore the characters’ feelings toward each other; you can play out a giant free-for-all battle with everyone in their mobile frames; you can meet with another character in a duel of swords, exploring the relationship through the metaphor of combat; you can have an intimate moment of one-on-one interaction, fraught with romantic and possibly sexual tension; and you can meet on the field of battle as parts of two units of soldiers exchanging fire and death. All of the games are designed to give players the opportunities (and encouragement) to create those messy entanglements, as each game is really about the relationships between the characters, even the games about battle. And all the games are designed to structure the interaction between the players to make sure they are aligned with each other no matter how the characters feel about the other characters. Who creates what part of the fiction is carefully controlled, and the games let you choose in what ways your character will be vulnerable to the other characters by letting you choose which questions you ask or what demands you make. Some examples: In the dance, you can ask questions like: “My face is close to yours. Do you turn subtly toward me, or subtly away?” and “When the dance ends, will you stand with me or rush away?” and “This moment in the dance allows me to step close to you and linger very near. Am I welcome?” In the conversation over food, you can ask questions like: “I make an ignorant social or diplomatic blunder. Do you let me recover gracefully or do you hold it against me?” and “I hope you don’t bring _ up. Do you?” In the meeting over swords, you can ask questions like: “I overreach slightly and you have the opportunity to slip in a dirty little cut. Do you take it?” and “You knock my sword rattling out of my hand. Do you allow me to recover it, or must I submit?” The one that I currently love the most are the exchanges in a tactical skirmish, where you make demands like: “Submit now, or my forces spreads itself too thin and you pick off_____, who is straggling” and “Withdraw now, or you ambush and capture __, my scout” and “Submit now, or you catch __ in a sharp crossfire and tear them apart.” I think the structure of this is brilliant. You demand the submission or withdrawal of the opposing force or force them to reduce your soldiers one by one. And each soldier has a name and a position, and is just a poor kid trying to support their cause. Are you comfortable destroying them slowly to win the battle? And in the next scene that these two characters meet, this spilled blood will be between them, both their willingness to kill and their failure to protect their own soldiers. How can that not create messy entanglements? Once the gameplay goes around the table once, any player can call an end to the game after a scene finishes. In the end, Firebrands is about consensual interactions, the respectful give and take that creates not only a conversation but every exchange we have as players and people. The game encourages you to make yourself vulnerable through your characters, and it urges you to explore the messy aspects of being human with other humans. It’s a sharp design. I am crazy excited to have received Seco Creek Vigilance Committee in the mail today! (I messed up submitting my address, so I delayed shipping--d'oh!)

Thanks, +Keith Stetson! So I finally got to read and study +Michael Miller’s original incarnation of With Great Power, and there is so much to love about it. It is a tightly designed game and a really well-written text.

I’m a big fan of games whose narratives are born directly from the specific protagonists being played, and With Great Power does so elegantly and without a lot of work by the GM. First, an agreed-upon “Struggle” loosely defines the theme of the session. Then, after brainstorming about their superheroes, players use the Struggle to decide on the 3-6 Aspects of their character to focus on, choosing those that best highlight the Struggle. The players then choose a single Aspect that will be central to the story, which is called their “Strife” Aspect. The GM, or villain player, takes all the superhero characters’ Strife Aspects and creates a “Plan” for the villain that targets all of them. In every scene, then, the villain player knows what Aspects she wants to target, how she wants to eventually gain control of them, and how she ultimately wants to transform them through the execution of her plan. That’s damn cool, and exactly the way I like to see situation and character meet up in an RPG. Aspects in With Great Power are themselves neatly done. Characters have no stats on their character sheet. In fact, other than their name (and a drawing if you’re into that), there is nothing on the character sheet except those 3-6 Aspects. Each Aspect has its own “Suffering” scale, 5 steps from Primed to Devastated. For each scene your superhero appears in, you choose an Aspect or two whose Suffering will increase or decrease. When you increase the suffering, you get to add cards to your hands, and when you decrease suffering, you remove cards at random from your hand. The greater the Suffering, the more cards you get to draw or discard. It’s a tightly designed pressure valve as players need cards to win their conflicts and defeat the villain’s plan. The incentive is always to put your Aspects at greater and greater risk, until they eventually become Devastated, at which point the villain player takes control of the Aspect. The villain player is of course angling for the Strife Aspects for her machinations, and since Strife Aspects give players additional cards, players will want to risk them especially. It’s a cycle that pushes the characters to the point of do-or-die, and I absolutely love that construction. With Great Power also uses cards in its resolution mechanic in a neat way. I love games that succeed in creating a beat structure with in conflict, so that players play out the thrust and parry in an exciting dance of action and reaction. Michael uses cards to create a dynamic conflict with detailed fiction and exciting interactions. It’s a smart design. And then there’s the Story Arc, which is a simple mechanic that ensures that the climactic stuff happens in the climax. Whenever superhero players lose a conflict, they can choose to fill in the next stage on the Story Arc. The Story Arc has five stages, and at each stage, the villain player has fewer tricks and resources. And it is only when the fifth stage has been reached that the heroes can devastate the villain’s plan or the villain can transform the heroes’ devastated aspects to complete her plan. Just a glance at the Story Arc page will tell the players where they are in the story and in that evening’s game. It’s not heavy-handed and seems like a solid pacing mechanic. Yeah, there’s a ton of neat stuff in the game and a lot to think about. I’m looking forward to Michael creating a blogpost of his own talking about why he decided to make the new edition of the game as a complete reimagining of the rules. Outside of noting how great the Swords without Masters approach is, I don’t want to speculate. But I will say this: In the creation of the Master Edition, Michael has successfully captured the spirit and tone of the original game. The heroes look almost the same, and though they consist of Elements rather than Aspects, they keep all the same qualities and feel. The villain is still created just like the heroes and still has a plan to be thwarted, even if the plan is much looser and made up as the game goes along. Both editions create stories of melodrama, focusing on the superhero as both hero and complicated human being with difficult relationships. For example, the Personal phase in the Master Edition is strikingly similar to enrichment scene in the Classic Edition. In short, it truly is the same game, even though all the rules have been changed, which is a pretty amazing feat. I'm working, real casual-like, on a short story game for 2 people that uses M&Ms as the randomizer.

The idea is that you're out with your friend, you want to play a game, but you have no game supplies. Walk into a convenience store, buy two individual bags of peanut M&Ms, and you're ready to play. There are 6 colors or M&Ms and there are numbers concerning their relative frequency in each bag. There are typically 20-24 M&Ms in a bag. At those moments of randomization, you reach in the bag for an M&M and follow the color. There'll be special rules for mutant M&Ms, like those ones with two peanuts under the same candy coating. Other possible affordances are the size of the M&Ms (especially useful if there is an opposed event of some kind), the stamping of the white "m" on the candy, the roundness of the candy, or definite cracks in the coating. I know, you want to play right now. The mail has been poppin' this week! Two kickstarters I backed have shown up, and the fruits of an evening looking through ebay arrived about the same time.

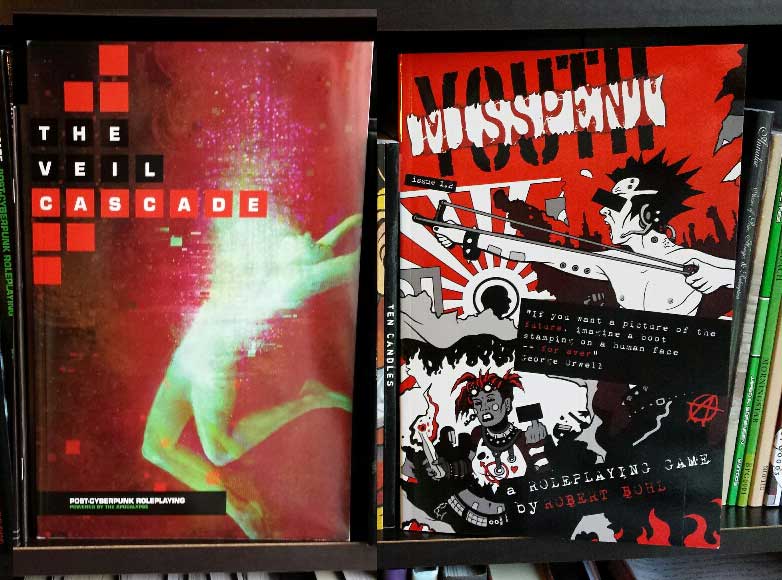

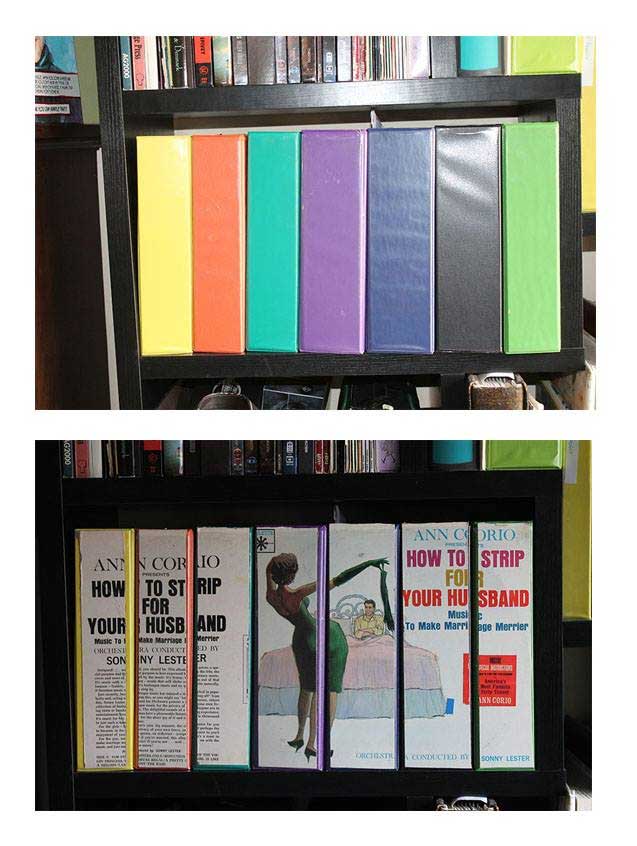

+Fraser Simons' The Veil Cascade has made its way from Canada, and it is as gorgeous and high-quality as the original book. +Robert Bohl's Misspent Youth in all it's b/w punk glory looks equally awesome. It's got a sturdy cover that looks like it can take a beating and thumbing through. +Ron Edwards's Elfs and S/Lay w/Me are two books I've had on my "to get" list for awhile, and I just happened to find good prices on them on the same night. The S/lay w/ Me is in great shape, bu the Elfs is a little brittle, but what can you do? Jacob Norwood's Riddle of Steel is a title I have been reading about for over a year and a half now, but the text is nowhere to be found, even as a PDF. The books available on ebay were always too expensive too, but I happened to find a copy at cover price, so I jumped on it. Excited to see what all the excitement was about. The book thankfully is in great shape. And finally, Matthew Gwinn's Hour Between Dog and Wolf is another title players I respect have been enthusiastic about, and since I had already spent money on the other titles, well, what could it hurt to drop just a little bit more? It's always easy to squeeze a 2-player game into an evening! Now back to behaving myself. I need to preface this photo with a confession.

I love print. I find it disorienting and unpleasant to read on an e-reader. I didn't want the RPG PDFs sitting on my computer to go unread, unplayed, and unappreciated. All of this is why I print out my RPG PDFs and put them in binders on my bookshelf. My awesome wife lately came up with a cool way to decorate using those PDF binders and cool album covers that she had picked up over the years. So here is a before and after picture. If you have binders that need a little sprucing up and album covers that need showing off, I highly recommend this technique. +Michael Miller's 2016 edition of With Great Power looks like a really cool game. This version, called the "Master Edition" - and you'll see why in a moment - is a complete reimagining of the game and very different from the 2005 version.

The Master Edition is "Descended from Monkeydome" - aka, it uses the system +Epidiah Ravachol designed for Monkeydome and - dare I say perfected? - for "Swords without Masters." This is the first game that is descended from Monkeydome that I have read, and it blew open a few doors in my mind to how a game can make use of the phases and tone-shifts that are at the heart of play in "Swords without Masters." Character creation looks like a blast, and as the hero players build their heroes, the villain player builds her villain, complete with monomaniacal master plan. There is a fantastic set of tables at the back of the book to inspire ideas for powers, origins, relationships, as well as the elements of the villain's plans. Everything about the game eases the creative pressure to give you something inspired to say that will push the story in interesting and productive directions. This is a tiny, but I think effective, example of what I'm talking about: After you use the random tables to jolt your thinking about your hero, and after you create a quick sketch of who they are, you are not allowed to give your hero a superhero name. Everyone else has to propose a name, and you can choose from that list, or reject them all an call for another round of proposals. It's a simple and effective solution to avoid creative freeze. All the things that make "Swords" an incredible experience are here - the prompting of other players to tell how their hero performs incredible deeds, the creation of a list of awesome things players say that eventually trigger the end game, shifting tones, unexpected stymies, mysterious questions that can only be answered as the game draws to a close. And to that, it adds everything you love about superhero stories, including how the heroes' super lives collide with their normal lives, as well as the piecing together by the heroes of what the villain is up to and how to stop her. The book is a great read, and the game looks awesome. Moreover, if you are interested in monkeying with the Monkeydome, this is a great place to start if you want to see how the game can be adapted and stretched. Check it out. Steal Away Jordan has so much cool stuff going on.

I love the creation of goals and tasks that drive all the action of play, and that the GM is not allowed to know what those goals and tasks are. I love the thematic impact of the GM's determining the PCs' "worth" at the beginning of play and at the end of each session. I love that minor bargaining and conflicts allow the players to gain temporary dice for upcoming rolls. The players are driven to create bargains and conflicts to better position themselves for future trouble. I love that accomplishing tasks builds up your "worth" pool for that major goal. Together, the players drive the entire story as proactive heroes, always pushing for what they want. I love that death is always on the line when you push a roll or gamble for additional luck. I love that you can play your own ghost if you do die. I love the use of "lucky sevens" thematically throughout the game. Steal Away Jordan is a sharply designed game. My only wish is that there was a little more guidance in the book for the GM. Oh, and if you're a fan of Poison'd, you should read Steal Away Jordan. The influence of Ellingboe's game on Baker's is prominent and interesting to see and compare. I just finished reading +Jason Morningstar's Grey Ranks, and it is a beautifully designed game.

Here's a brief overview of the things I love about it: I love that character creation and character discovery happen together in the first chapter of play. A full game plays out over 10 chapters through 3 full sessions. The first chapter is divided into three parts: character creation, the first mission, and the finishing of character creation. You first establish enough details to know how to play your character. Then after you run a diceless mission, you establish what your character cares about and what their reputation is among the other PCs—or in other words, you figure out why you play your character. I also love the built in death spiral that is avoidable, but only with some miraculous rolls of the dice. It is almost inevitable that the losses will pile up and the characters driven toward losses both personal and political. As it was in history, the Uprising is a lost cause. We are playing to figure out what our young characters can make of it and what it will cost them personally. I love the way growth and change is mapped in the game. Characters’ reputations begin as negative traits that can eventually be turned into a positive opposite to show their growth. Similarly, the grid that is the center of play maps the constant ups and downs that makes up the trajectory of the character’s emotional state. I love the support the game gives the players to create missions and personal scenes. Between Radio Lightning (a radio broadcast that precedes each chapter of play with a bit of data about what is the state of the Uprising on that specific day) and the selected situation elements (derived by where your character is on the shared grid) and what has already happened in the story, players have everything they need to create unique and gripping scenes. It is especially cool that elements can be reused and reintegrated into the story to create natural call backs and recurrences. It’s such a simple and effective way to create such a literary technique that it borders on brilliant. I love the use of Reputations to give you larger dice and the use of the Thing You Hold Dear to give you rerolls. These tools create a natural changes in both the characters and the narrative. Players will feel the natural desire to use them followed by pleasure in seeing them enter the fiction both thematically and dramatically. One by one, the Things Held Dear will fall in the name of keeping back the darkness. Players would have to work actively against the system in order to not have a beautifully and painfully tragic tale of loss and coming of age. Everything in the rules takes you where you want to be. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed