|

I’ve had a lot of fun reading and thinking about Jonathan Tweet’s 1995 RPG Everway.

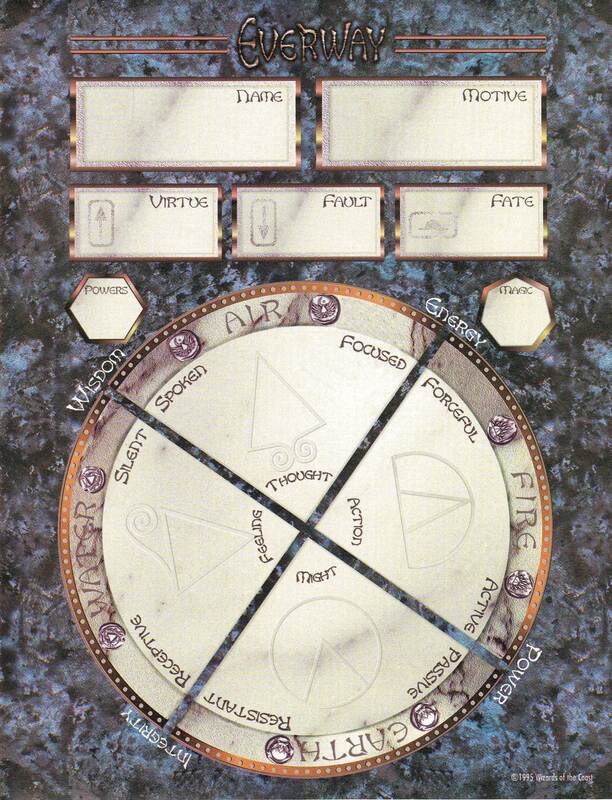

I knew going into it that the game used a “Fortune Deck” and a set of “Vision Cards” in some way, and I knew that Tweet, at some point in the text, makes the distinction between 3 approaches to resolution: karma, drama, and fortune. That’s the sum total of what I knew when I dove in. The game box includes three 7” x 8.5” books: a 160-page “Playing Guide,” a 14-page “Guide to the Fortune Deck,” and a 64-page “Gamemastering Guide.” You are instructed to start with the “Playing Guide,” to which both character players and GMs are openly invited. A little over the first third of the book is devoted to establishing the setting, a fantasy multiverse of worlds that the players can travel between via “gates.” The game itself is named after the main city in the main realm in the main sphere. Play is designed to create episodic and epic narratives as the PCs move through the spheres (spherewalking, as it’s called) solving problems and getting tangled up in local customs, mysteries, and what-have-yous. The next chunk of the “Playing Guide” (again, over a third of the text) is dedicated to character creation. Character creation in the game is really cool, using the “Vision Cards” to inspire players. The vision cards are regularly-sized cards with images of characters, situations, locations, scenes, and mythical creatures. They are beautiful and mysterious, working to suggest things but leaving a lot unanswered and only hinted at. The game comes with 90 of these cards, and there were two expansion sets of 90 more cards each produced before the game line was canceled. You spread out these cards on the table, and the players pick five cards to serve as inspiration for their characters. The cards might represent the character herself, someone important to her, where she comes from, the scene of some pivotal moment in her life – whatever the cards inspire. It’s a really cool way to begin character creation because the pictures can push you in directions you would not think to go, and the pictures in conjunction with each other can only drive you further in unexpected and interesting directions. And because all the cards are thematically appropriate to the tone and subject matter of the game, every character derived from the pictures will be well suited to the same universe. I also appreciate that the designers were thoughtful in their representations so the cards have people of every skin color represented, and most cultural depictions are non-Eurocentric. After selecting 5 cards as the inspiration for your character, the players share the cards and explain what they have drawn from them. Then players are invited to ask each other questions about the cards and the character being developed from them. This is the first game I know of (although my pool of knowledge is admittedly shallow) that has questions from other players as an explicit part of character creation. It feels like very modern tech, and I love it. The “Fortune Deck” is also used in character creation. The Fortune Deck is a deck of 36 cards, modeled on the major arcana of tarot decks. Each card has a regular “meaning” and a reversed “meaning” when played upside down. I put meaning in quotes because the printed meaning is hardly definitive. Like everything else in the game, the cards are suggestive and up for interpretation. For example, the Autumn card means “plenty” and reversed it means “want,” but what plenty and want mean can range through a great number of possibilities. In character creation, the players go through the cards of the Fortune Deck and pick one card to represent the character’s Virtue or strength, another to represent her Fault or weakness, and another to represent the character’s Fate. For the Virtue and Fault, you pick one meaning from the card, but for the Fate, you consider both meanings to create a set of poles for your character, the two possible paths you see before the character. For example, if you select The Fool, your two poles would be “freedom” on the one hand and “lack of connection” on the other. That could mean whatever you want, or you might not know exactly what that means at all but it feels right. Your character is forging her own path but runs the risk of isolating herself as she does so. What’s cool about all of these elements of character creation is that they are about how you as a player want to play your character. Who they are, what motivates them, where they are going, and where they have been. Moreover, each element potentially adds to the depth and complexity of your character and has the opportunity to push you into a direction you hadn’t considered, making the character’s starting form somewhat surprising to you as a player, which I find very attractive. The game uses the four elements to structure the characters’ stats: air, fire, earth, wind. That alone sounds clever but uninspired, but the execution of the stats is really well done. The real accomplishment is the presentation of the stats on the character sheet. Here’s how the book defines each of the stats: “Fire measures vitality, force, courage, speed and daring.” “Earth governs a hero’s health, endurance, fortitude, will, determination and resilience.” “Air determines intelligence, speech, thought, logic, analytical ability, oratory, and knowledge.” “Water governs intuition, sensitivity to that which is unseen and unspoken, receptivity, psychic potential, and depth of feeling.” All of those are reasonable categories. I’ve included a scan of the character sheet so you can see how the stats are mapped out there. You can see that each element is presented as a quarter slice of the pie. At the point of the slice is a one word summary of the element: Action, Might, Feeling, and Thought. Then each slice is joined to its neighbor by a commonality. Air and fire are both about energy, but air is a focused energy and fire is a forceful energy. Both fire and earth are about power, but fire is an active power and earth is a passive power. Earth and water are both about integrity, but earth is a resistant integrity and water is a receptive integrity. Finally, both water and air are about wisdom, but water is about silent wisdom while air is about spoken wisdom. This map defines all the corners of each element and does a great job of defining at a glance what each element covers during play. The problem with abstract concepts for stats is that they are work for players to remember during play, but the character sheet allows the designers to keep the flavor of the elemental division while removing the burden of memory from the players. For me, the visual design of the character sheet is as important as the conceptual design of the statistics. I’ve already rambled on too long, so I’ll skip discussing magic and powers for now. The reason I’ve spent so long on the character creation is because character creation and the resulting character and sheet are one half of the game in play. Everything the players need to play the game is there on their character sheet, and a great deal of what the GM needs to run the game is there on the character sheet as well. After covering the setting and detailing character creation, the rest of the “Playing Guide” and the entirety of the other two books are really about running the game as GM, but there aren’t really any “rules” to speak off. The system of play for Everway is entirely reliant upon the GM. The players say what their characters do and the GM determines the results of that reaction. That is the entirety of play in a single sentence. So what the remaining 80 or so pages of text are about teaching the GM how to make those decisions fairly, dramatically, and creatively. I expected the discussion of karma, drama, and fortune to effectively be a short essay within the text, but it’s really so much more than that. What Tweet does in the text is effectively attempt to breakdown what GMs do when answering the question what happens next? Sometimes the GM just decides that the action is a failure or a success. They look at the character sheet and decide that the character is or isn’t strong enough, magical enough, talented enough, or whatever to do the thing they want to do. Or the GM looks at the fictional positioning and decides that the character’s approach or tactic is likely to be effective or not. After evaluating the measurable facts of the situation, the GM declares success or failure. That whole process is called “karma” by Tweet. Sometimes the GM decides that it would be dramatically exciting if a character fails or succeeds or that things go sideways instead. Sometimes the GM decides that the character can’t get what she wants because it would short circuit the entire mystery or defuse the entire situation too readily. That decision process is called “drama” by Tweet. The dramatic ruling is based entirely on matters of the story and has nothing to do with what is likely or what a character is capable of. Finally, the GM sometime leaves the results of an action up to fate and employs some kind of randomizer, dice, cards or whatnot. That’s what Tweet calls “Fortune.” In the case of Everway, the GM can draw the top card from the Fortune Deck and interpret it as a favorable sign or an ill omen. The rules are very explicit that all of these ways of making decisions will overlap and occur concurrently. There is also a matter of taste, some GMs preferring to decide things by karma, others preferring to leave things to fortune, and still others constantly thinking of the dramatic impact of the actions on the story. But whatever your leaning as a GM, you draw on all three methods constantly. I found the analysis compelling and the breakdown impressive. The text is really an extensive guide to how to make decisions as a GM with a particular focus of how to GM this game. The guide teaches you how to interpret the statistics to determine likelihood of success, how to look at the prongs of the story to determine what is up for grabs and what needs to happen without interference, how to read the fortune cards to determine if they bode ill or well, all in an effort to teach the GM to be a fair and impartial judge of the character’s actions and the ramifications that follow. I of course had problems with plenty of the particulars. The discussion surrounding reading the outcome of a sample fight reminded me of nothing so much as Erick Wujcik’s Amber. In both game texts, the game wanted to use the numbers to determine outcome while still allowing for surprise and unexpected outcome, leading to a coy game between players and GM as the GM determines what course of action will be especially effective and the player tries to meet the GM’s determination. In the end, such play measures success by one player’s ability to read the mind of another, which is a pretty shitty system. And the idea that a GM will undermine a clever player by refusing to validate a character’s action because the GM is committed to a particular plot is offensive to modern RPG sensibilities. But these problems I had didn’t impact my ability to appreciate the crux of Tweet’s analysis. There’s nothing about the system itself that helps the players have an interesting and compelling game, since the system is the GM. There are no mechanics to propel play or story, nothing other than a set of resolution tactics, so I imagine that play is exactly as interesting as the skill of the players involved. With an inspired GM and lively players, I can see some very fun games coming from play, but there is nothing to keep the game from being ho-hum or even downright dull if the players and GM are unsure of themselves because there is nothing mechanical within the game to catch them and support them. The closest the game comes to providing a means to keep things lively is the Fortune Deck as a surprising tool for resolutions, and I do love the possibilities it holds.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed