|

"A fully armored man can move 120 feet per turn at a cautious walk. Each turn takes ten minutes (scale time, not actual) in the characters' magical universe."

Damn, that's some cautious walking: 5 seconds for every foot walked. If you have a two-foot stride, that's 10 seconds every step. "An unarmored and unencumbered man can move 240 feet per turn [or 5 seconds per two-foot stride], and armored man 120 feet, and carrying a heavy load only half that [or 10 seconds per one-foot step]" "Time must be taken to rest, so one turn every hour should be spent motionless - i.e., one turn out of every six." - Dr. Holmes on the cautious walking of dungeoneers, page 9 ---- Running is defined as "triple normal speed." According to the table, an "unarmored, unencumbered man" can move normally at 480 feet/turn. Triple that is 1,440 feet/turn. That means that the character moves 2.5 feet per second, which seems like a pretty comfortable walking speed. Put another way, that's a quarter mile in 10 minutes. People in Holmes's D&D are not swift-footed.

1 Comment

"When a character is killed, the lead figure (if used) representing his body is removed from the table, unless it is eaten by the monsters, and carried off by his comrades to be returned to his family."

On faith that your comrades will care enough about your corpse, Dr. Holmes's D&D, page 8 That "unless it is eaten by the monsters" kills me. "If a character is killed, then for the next game the player rolls a new character. The new character, of course, starts with no experience. A character may be allowed to designate a 'relative' who will inherit his wealth and possessions (after paying a 10% tax) on his death and disappearance."

The harsh reality of death in Dr. Holmes's D&D, page 8 Yes, there is a death tax in our fantasy world, and I love that "relative" is in quotes, suggesting that the law of inheritance may be abused by claiming to be a relative when you're not really one. "At the Dungeon Master's discretion a character can be anything his or her player wants him to be. Characters must always start out inexperienced and relatively weak and build on their experiences. Thus, an expedition might include, in addition to the four basic classes and races (human, elven, dwarven, halfling-ish), a centaur, a lawful werebear, and a Japanese Samurai fighting man."

- "Additional Character Classes," pg 7, in Dr. Holmes's D&D I clearly never read this as a child, or I would have a stack of werebear and centaur character sheets. "[A] female with high charisma will not be eaten by a dragon but kept captive. A charismatic male defeated by a witch will not be turned into a frog but kept enchanted as a lover, and so forth."

The measurable advantages of a high charisma in Dr. Holmes's D&D. Do you wonder where the tradition of the asshole thief who steals from her own party started?

"Thieves are not truly good and are usually referred to as neutral or evil, so that other members of an expedition should never completely trust them and they are quite as likely to steal from their own party as from the Dungeon Master's monsters." Baked right into the rules by, at least, Dr. Holmes's D&D, page 6. I need to run to a job, so I wrote this rather quickly: please forgive the sloppiness of thought and execution.

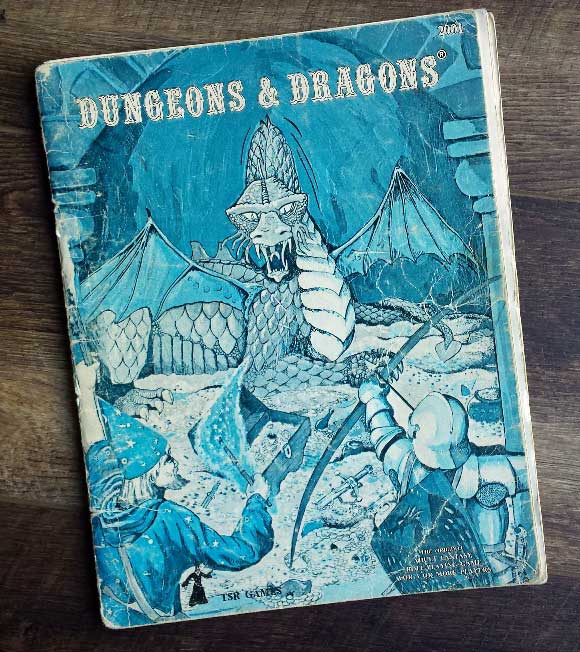

I didn’t expect to post another #claytalk post, but I had unexpected insight, which wasn’t really insightful once I saw it, more of an “oh yeah, of course” moment. I had been intrigued by the notion that name tokens were the only tokens you could spend directly, and I knew that was important, but I didn’t follow the logic all the way out. I knew that name tokens were central to the game, and I knew that creating a better society in the Degringolade (or failing to create a better society) was the end state of the game, but I didn’t put the two together. Name tokens can be spent, two at a time, for something called “regard”: “During play you can spend two [name tokens] to ensure a gamemaster character is successful in a planned, future action for which no player minotaur will be present. This is called regard. All you do it tell the character about your confidence in what they plan to do and spend your two [name tokens] back to the gamemaster’s set, and then when that character takes the planned action they’re successful” (105). See what your minotaur can do there? Influence the outcomes of the actions of human beings. Name tokens have as similar power in the Krater draw, but of course the outcome is uncertain. When a name token is in the pool, possible outcomes include “Your efforts change the mind of the opposition,” “A likely threat or opposition ducks out or doesn’t materialize,” you get “An abiding gift and a [gift token],” and there is a “momentary delay as you and the opposition learn to respect each other.” Name tokens are your minotaur character’s main way to influence the thoughts and actions of others, including those more powerful socially than yourself. So while you start out a menial laborer, almost a peripheral character in the movings of the gamemaster characters, the arc of the game is likely to take you to a place where your name tokens are piling up, enough for you to create desired Krater outcomes, and enough for you to be able to spend to influence the actions of the gamemaster characters. It’s not a direct power, but it is an important one that lets you exert your own will on the events in the Degringolade. The post that got me there was a response Paul made to a question about how regard works. You can find the original post here: (https://plus.google.com/101456219798191255548/posts/hVokoncb44S) I’ll retype Paul’s response to save your having to click over: ”I'll tell you a secret. This is pretty close to the core theme of the game. Getting to the point where you're refreshing more Name tokens than you need for Krater draws, and then what do you do with them? “I thought calling it ‘Regard’ was explanatory, but your examples suggest the mechanic could be better described as a procedure in the text. I think actual evidence of "regard" is important. So the player minotaur has to be aware of a planned action by a gamemaster character and to somehow express approval. It is a leadership behavior. It can happen from a gamemaster character coming to a player minotaur and informing him of a planned action, and the player minotaur saying "okay, do it" or even just "I won't stop you." Or perhaps the player minotaur finds out some other way and expresses their approval to a third party. And then they spend the tokens so it succeeds.” I read that and thought, to paraphrase the Dude, “Oh yeah, Maude, my thinking about this case has gotten so uptight.” Now there’s a whole analysis that can be done about the game’s representation of power and influence and how social power is conferred, assumed, and used, but I’m not the guy to perform that analysis. If you are, please tag me when you post your analysis. I’d love to see it. (If you are interested in my other #claytalk posts, you can see the previous one here: https://plus.google.com/102721916927145169256/posts/KJLsMtZRytj) As I wrap up my thoughts about The Clay that Woke, I'm starting in on Eric Holmes's 1979 edition of D&D. This is the first RPG I ever played. I was only 6 at the time, and my brother, 10, ran the game. We used the chits that came in the boxed set. It is the oldest book in my collection, and one of the few preserved from my childhood. I don't know if I've ever read the book all the way through.

I'll still be following the claytalks hashtag as I move ahead with my studies. It’s time for more #claytalk! This time we’re talking about silence.

(If you missed my previous posts and are interested in reading them, here’s a link to the previous post, which you can follow backwards to the first post, if you want: https://plus.google.com/102721916927145169256/posts/dbH1KeFyeeE) Silence is a living philosophy The first thing I’d like to observe about silence is that every time it is described in the text, it is worded differently, without any single definition (for lack of a better word) covering everything. On page 18, we are told “Wild and fatherless [the first four minotaurs] didn’t naturally find a life in the society of men – not until they achieved silence. Silence is the minotaur philosophy of life conduct: puruse the social good, and pursue justice; do not want; do not use the names of women.” A few pages later, on page 22, we get this: “Over the centuries minotaurs have developed their cultural philosophy of silence: be contemplative, do not want, do not use the names of women, and do not express your emotions, for breaking silence in these ways is an expression of need.” Yet still later, on page 43, we are told, “Over the decades they developed a philosophy of life conduct: pursue justice and the social good; be courageous; act with wisdom; do not want; do not use the names of women.” Finally, each character sheet as the same definition of silence: “Be courageous. Act with wisdom. Work for justice and the social good. Do not use the names of women. Do not want. Do not express your emotions.” I propose that these differences are not an error in editing, but a purposeful inconsistency. None of the definitions contradict each other, but none of them is complete either. This is because the philosophy of silence is just that, a philosophy, not a strict code or a mantra. It is something felt, something more extensive than a few catchy phrases, something to be lived, not just listed. These variations communicated the living nature of silence. A brief look at the problematic nature of gender in the text and game The most complete list, and the one that will undoubtedly be the guiding principle in any given game, is the one provided on the character sheets. This is the one the players will constantly be consulting and interpreting. But it is worth noting that every variation includes the two elements “do not want” and “do not use the names of women.” We are told that this last stricture is because “There are no female minotaurs, so nicknames are an effort to create distance from want.” In this game, women can be friends, employers, coworkers, and lovers, but each and every woman, by the very nature of her being a woman, is a potential object of want, which makes them first and foremost objects of sexual desire, no matter what other role they may have in society. That is problematic to say the least. This de facto categorizing of women as objects of sexual want is further troubled by the repeated use of the word “men” to stand in for human beings within the Degringolade. The original minotaurs “didn’t naturally find life in the society of men” (page 18), “Untamed and troubled they didn’t easily find a life in the society of men” (page 43), and silence has “enabled [minotaurs] to live will among men” (page 43). It is clear from such passages (and many others) that the Degringolade is a solidly patriarchal society, in spite of many Empyrei being women. The game has very good reasons, I think, for focusing on men, but this treatment of women is disturbing, and I would not be surprised if many women and men are put off enough to not want to bring the game to the table. Why would players troubled by the patriarchy want to play a game in which patriarchal attitudes are so deeply interwoven into the material? But perhaps the game provides avenues to upset the patriarchy by finding a way to redefine masculinity and recreate the society we are given at the start of the game. We are told that the watchers, the giant leafless, bloomless trees that stretch out over the jungle canopy, “will fully frondesce and bloom again when the city below enters a new age of greatness” (page 16), and we are told that we’ll “play until it’s clear whether the watchers will frondesce and bloom again for society’s entrance into a new age of greatness” (page 22). Perhaps part of this new age of greatness will not include women being first and foremost objects of male desire. Obviously the fate of the society is bound up with the minotaurs we play, and the minotaurs are bound up in masculinity, so perhaps the solution to the one is naturally a solution to the other? Having not played the game, I don’t know if that is where the game goes naturally. I don’t see anything in the mechanics that makes that likely to occur, since the course of the game is bound to the desires of the players, but that seems like something that could happen if the players pushed for it. I’m just not sure the game cares whether you push for it or not. Let’s move on to why the minotaurs are all male in the first place. Why only male minotaurs? It’s clear Paul wants to say something - or explore something - about masculinity through The Clay that Woke. A brief look at the philosophy of silence reveals elements of what it means to “be a man” in various cultures throughout history. Being courageous, being wise, keeping tight reins on desire, not expressing emotions—these can all be seen as foundational tenets of western manhood. But before we delve into what the game is saying about masculinity, I want to take a moment to look at how making all minotaurs male gives the games narrative energy. The tension at the center of the fiction created by The Clay that Woke is the uneasy position that the minotaurs occupy in the human society of the Degringolade. Minotaurs are creatures that span the two realms of the game, with one foot in the jungle and the other in the city. They are both wild animals and civilized people, and silence is supposed to be the means by which the minotaurs can live peacefully and somewhat harmoniously among human beings. The whole reason minotaurs need to fit in with human society in the first place is the fact that they are all male. If the race of minotaurs hopes to survive the current generation, they need to mate with human women, and the same goes for every generation that follows. Only human men mating with human women will produce future women for future mating, so minotaurs cannot drastically upset human civilization without compromising their own future. That is a brilliant position from which to make dramatic fiction. It’s a classic case of not being able to live with them and not being able to live without them. No matter how frustrated minotaurs might get with human men and women, they cannot say fuck it and run off to the jungle permanently. But individuals don’t always think of the whole, so there needs to be some mechanism in place to protect the herd by shaping the individuals’ behavior. That’s where silence comes in. Silence creates a code of personal conduct that ensures that each individual minotaur can coexist with humans in their city without jeopardizing their own well-being or the well-being of the herd. If the larger social tension is created by minotaurs needing to exist within human society, then the localized tension within each minotaur character is created by the need to achieve silence by suppressing half of their own nature. If we look at the six elements of silence as they are written on the character sheets, half of them are aspirational goals (be courageous, act with wisdom, work for justice and the social good) while the other half are restrictions on their behavior (do not use the names of women, do not want, do not express your emotions). Actually, the goal of not wanting goes beyond controlling behavior and seeks to limit natural impulses. Achieving this incredible state of self-control would be hard enough in an ideal setting, but doing so while being second-class citizens makes it all but impossible, which the text alludes to: “Human society employs them for menial and dangerous and brutal work. So, not surprisingly, they often fail to live up to the ideals of their philosophy” (page 43). The larger tensions aggravates and ratchets up the individual tension, which again makes for excellent drama. Silence as a part of play The beautiful part of the game is that the game mechanics surrounding silence create tensions in play that mirror the situation I describe above. How do you force players to play their minotaurs as the game demands? How do you make them feel the pressure to achieve silence? Those silence tokens do so much work! I love that the GM is instructed to take away silence tokens when a minotaur PC breaks silence. The player doesn’t pay a token to break silence; the GM takes it away if they do. It’s a subtle difference, but an important one, both thematically and psychologically. Starting with three silence tokens means that you get to break silence three times before the GM takes control of your character and sends them to the jungle, possibly with a trail of broken human bodies in their wake. The player needs to choose carefully when their character will break silence and when they’ll adhere to it, which invites the GM to have her own characters apply pressure to see what the characters are willing to break silence over and what they are not. It’s a brilliant setup because the players don’t need to read a book full of fiction to understand the difficult position the minotaur occupies because the silence tokens and rules that govern their behavior let them feel it directly. It’s a powerful statement when a game’s mechanics can do that work instead of requiring long explanations and discussions about players’ buy-in. Once the GM knows what kind of world needs to be presented to the players, the players just need to respond to the GM and the pressures of the mechanics. Oh! And then there is the list of how their character broke silence that they have to maintain on their character sheet—oooh, I love that. It does so many things at once. It is a reminder of the critical moments that have happened before; it is a way of making sure the player knows why their silence token was seized by the GM as the philosophy of silence meets the real world; and it is a list of the minotaurs shameful moments, like writing on the chalkboard 50 times, and like the list the minotaur repeats to himself when he is torturing himself at night with a list of his errors. The two halves of the silence philosophy are naturally at odds with one another, because to pursue justice and the social good assumes a desire in the minotaur for justice. There’s the excellent bit of fiction in the text of when the narrating minotaur confronts Feru, the maker of the poison that affects the young wives of Saemung Empyreus, in his shop. He is working for justice and the social good, but he is also acting out of his own desire to be a protector and to stop this asshole. As he runs out of the store it is clear that he broke silence by confront Feru even as he acts to uphold silence. So silence and the minotaurs’ status as second-class citizens work to create an ever-unsettled situation that the minotaurs are forced to navigate. Silence is an unsteady platform upon which the minotaurs are forced to do a balancing act, only the fulcrum and platform have no point of equilibrium at which the minotaur can rest; instead they are constantly shifting their weight to steady themselves, which they can never do. It is a Sisyphean task, but it makes for self-propelling drama, which is great for an RPG. There’s of course more to say about silence in spite of how long this post is. I didn’t even touch upon how silence works with names to create the back and forth between city and jungle as the basic engine of movement in the game. But I’ll leave it here. Tell me your thoughts, what I missed, what I got wrong, what thoughts I’ve spurred you on to. Go on, break silence. Back for more #claytalk!

(My first post, in case you’re interested, is here: https://plus.google.com/102721916927145169256/posts/1MqG9M914Ty) Today I want to talk about the intermixing in the text of fiction, setting information, and rules in The Clay that Woke. I’ve seen passionate reactions to fiction appearing in RPG texts. I’ve never had strong feelings one way or the other, but I will admit that I usually skip over it. I tried to read the opening narrative in the new_7th Sea_ core rulebook, but when I saw that it when on for, my god, 8 full-sized two-columned pages, I flipped right past them. I knew coming into The Clay that Woke that some significant portion of the text was narrative, and I can’t say I was excited about that. But nor was I dreading it. I greatly enjoyed Paul’s writing in My Life with Master, which is the only other text of his that I’ve read, so I was confident that it would at least be an enjoyable read. But now that I’m 60 or so pages in, I find the fiction to be much more than merely enjoyable. I think this particular use of fiction alongside passages that detail the setting and passages the explain the rules creates a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. The reason I think it is effective is because we read fiction differently than we read how-to instruction, and we read setting material differently than we read either of the other two types of passages. Switching between them – at least in the specific context of The Clay that Woke - has a cool effect on me. I’ll try to explain further. The first section of text in the book is a bit of fiction, though one without a narrative. It is more of a vignette that situates us generally speaking in the world. We are obviously in a fantasy setting of sorts, with minotaurs, bronze weaponry, and a crumbling city surrounded by jungle. We are given not only physical features but hints at social structures, a sense of cultural decadence, and a storied past that reaches back millennia. I found myself very patient with the hints and suggestions of things in the world, such as a reference to bygone figures like Sulunia Empyreaus and Veturro the gladiator, and to geographical features like the stone faces whose meaning is long gone, the Tower of Heroes, the Vadhmriver, and the tall, leafless trees that stretch out over the jungle that are simply called “watchers.” I was more than patient, I was excited by the glimpses of the world that could not be contained in this one passage. That excitement is due in large part to the fact that it was fiction. Every science fiction or fantasy story makes reference to a world far larger than what you can see in any opening scene. You read actively (or at least, I do) looking for clues and bits and wonder how it will all come into focus later, for you believe that in fact it will all come into focus later. Using fiction puts the reader in the state of accepting that more will be revealed if you are patient and read on. If the fiction had gone on for long, my patience probably would have shifted to anxiousness, wondering when we would be getting to something good, so it is important that at the bottom of the second page, the author assures you that you will be learning about the game, not just the world. This is the paragraph that ends the first section: “The Clay that Woke is a roleplaying game. You play nameless minotaurs living and working among the people of the Degringolade and the dangers of the jungle. A gamemaster brings the world to life by creating your employment circumstances and creating and roleplaying all the beings of the Degringolade and jungle. You’ll try to uphold the difficult, stoic minotaur philosophy of silence, and you’ll earn a name” (16). That single paragraph brings in the elements we just read about: minotaurs, Degringolade (the city), the jungle, the presence of humans, and that minotaurs are in their employ. Doing so assures the reader that the fiction is directly related to the game. Even more importantly, the final paragraph points to things that were not in the fiction: the “stoic minotaur philosophy or silence” and the idea that “you’ll earn a name.” That’s the point that I got excited about what this form of writing could do as the fiction launches us into the rules and the rules launch us into more fiction. And indeed, the next bit of fiction brings up the idea of “breaking silence” and earning a name, as well as showing us what sort of encounters one might have in the jungle. Both forms then hint at things beyond themselves and both promise that all questions will be answered if you only read on. Over time, I found myself reading the rules with the same creative engagement that I was reading the fiction, as everything pointed both forward and back in a kind of crisscrossing of information and ideas. When reading a rulebook, you expect things to be laid out in logical steps. First I’ll tell you about A, which then prepares to you learn about B. And if you understand C and D, you’re ready to see how E brings it altogether. It’s very linear and in a lot of ways an illusion, as everyone who has tried to write such an instructional text knows. As you try to figure out how to present the material, you realize that you need to introduce the idea of B before you can really explain A, but for B to make any sense, C needs to be on the table, which first requires an explanation of A. That muddle is one of the reasons everyone says that you can learn best by playing, because then everything can be taught almost at once, and it’s why a second read is always more edifying than a first. Paul’s way around that muddle, it seems to me, is to invoke the way we read fiction, a fantasy novel which shows us parts of the world while referencing names and ideas that will become clear in time as we follow our protagonist around. You get things pointing forward and pointing back, preparing you for new stuff and reaching back to pick up and secure things that were only hinted at before. It is the journey through the text that brings everything together, organically. In fact, the index that stands where a table of contents should be is a perfect emblem of the book. There is an order in heading and subheadings, but the numbers that follow the words dance forward and backward, stretching several pages here, and touching upon a page briefly there. Run your eyes down the index and watch the number reach back and forth, sometimes in large steps, sometimes in small. Everything in the dance has linked arms with everything else, both numerically and conceptually. It’s very neat, and makes, I think, for a very rewarding read. The reason fiction is traditionally irritating in RPG texts is that they fail to be intrinsic to the text. They are flavor and contribute nothing but that. What Czege does is make it so that the fiction and the rules and the setting descriptions lean upon one another. In the case of The Clay that Woke that decision seems reasonable because the rules don’t exist as mechanics clothed in the setting of Degringolade and the jungle. The sinew of the mechanics is inseparable from the muscle of the world in which they exist. To play the game, you must understand the world, and to understand the world, you must know not only facts about its people, culture, and physical properties, but you must know the living breathing life of those things as they are communicated through the fiction. Had this game drawn on genre tropes and fictional worlds already familiar to the reader, then there would be no need to present the information this way. You could say, you know this film? It’s like that. It’s effective also because the scope of the world in the game is limited. The Clay that Woke involves one (albeit vast) city and one (equally vast) jungle, not a whole planet or system of planets. The game involves minotaurs and humans, not an endless network of species and cultures. The restrictions of the scope of the game played limits the scope of the world at issue so that this particular presentation can accomplish what it wants to accomplish. Okay, that was much longer than I intended. Forgive me if it is long-winded and wandering. I do not have time to revise my writing much due to lack of free time. If I edited these the way I wanted, I’d post one a month. It’s time for some #claytalk!

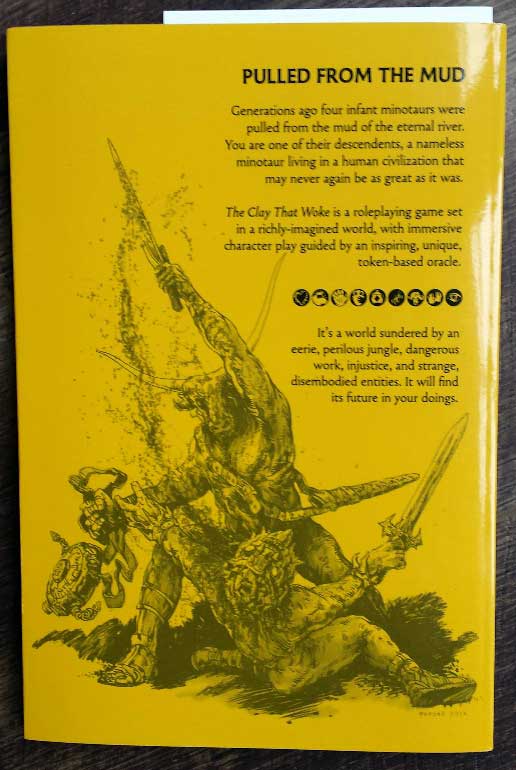

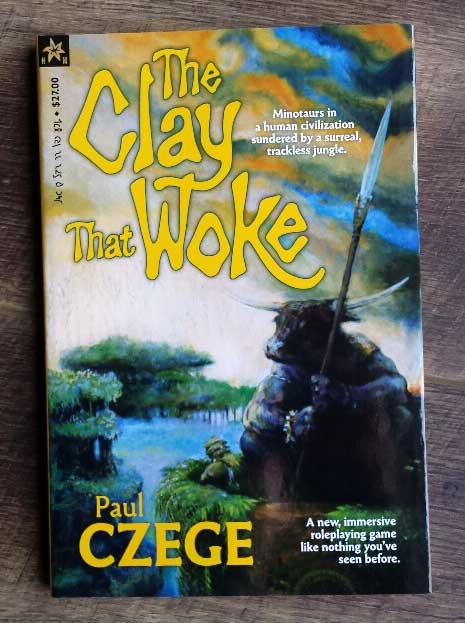

What do you do when you first start reading a book? You’ve decided you’re going to read it, you’ve picked it up and have it in your hands – now what do you do? What’s your ritual? Here’s what I do, and here’s what I did with The Clay that Woke: I read everything on the front and back cover. Seriously, everything. I take in the art and the graphics, and the little bits of information that are hinted at in the text. Minotaurs in a human civilization? Surreal? Trackless jungle? (I don’t know why, but I love the word “trackless” there – a great way to denote its untamed nature?) Immersive? I love the front cover art and the colors, and I love that the back cover art is grayscale on the yellow background. I love that the peacefulness of the front cover art is contrasted with the violence of the back cover art. Damn that backcover art is dynamic! That blood spray! Damn! I make a note of the name Marcel on the art to see who that is. I see the mythological origins of infant minotaurs being “pulled from the mud of the eternal river.” I linger over the 9 icons and puzzle over them only briefly. I remember that tokens are a part of the game, but I didn’t realize they were part of an “oracle” within the game. The word “injustice” catches my eye. From there I normally go inside the covers, but in this case there are flaps on the covers that contain additional information. First the inside flap of the front cover. I read the overview of the 11 tokens and their nine icons. Courage, mind, name, silence, gift and life tokens for the minotaurs. No and skull tokens for the GM. Red, bright, and still voices for the “supernatural entities in the jungle that are known to take an interest in minotaurs. I am intrigued. The inside flap of the back cover has play advice about “what to put into the Krater. I learn that there will be dangerous situations that players will want their minotaur to overcome. I learn there is a riskier response to dangerous situations that can put a player’s minotaur’s life at risk. I learn that there will be social conflicts that players will want their minotaur to overcome. Sometimes player’s will be amenable to a compromised solution to social conflict. Sometimes players will want instead to change the other participant’s mind. Sometimes the particulars of the conflict are less important than what you learn, I surmise, since there’s a way to “learn things about the world of the current situation.” I learn you can try to short circuit a potentially violent outcome. I learn that sometimes a player’s minotaur might be in the presence of a “Voice” without knowing it, and that if the player play’s that moment right, the minotaur can receive a “gift of a unique object or power.” I haven’t even opened the book and I feel like I have a smattering of ideas about what the book and game is about. It’s a pretty great design because on the covers alone the reader is introduced to major themes, flavor, and play content. I know there will be some strategy involved by what tokens a player choses to put into the “Krater.” I’m intrigued and want to know more about these supernatural entities in the jungle and this “Voice”. I want to know about the minotaur culture and how it interacts with the human culture. I’m interested to know how the game balances “dangerous situations” requiring courage and “social conflicts” requiring mind. I’m intrigued by name tokens and what it means to be a “nameless” minotaur. I’m intrigued by the idea of the Krater and how the GM and players create the pools of tokens from which the player presumably draws a result. In short, I’m left with a lot of half-knowledge and suggestions whose questions I know will be answered as I read. I’m struck by the care of what I’ve read so far. I trust the author and the book at this point and am excited for more. After exploring the covers, I usually look at the end of an RPG text next. There are normally design notes, thank yous, or other parting thoughts that for some reason I like to read first. Here, I find the sentence beginning “The Clay that Woke is inspired by RPGs with rich, troubled settings like Jorune, and Earthdawn, and Ruby, by Greg Saunders, by Finite and Infinite Games, by James P. Carse, and by weird ancient civilizations in Gene Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun and Paul Park’s The Starbridge Chronicles." I read through from there to the end of the book. I linger on the final full-page art and have no idea what I’m looking at, but I like the slimy insect in the foreground and the quoted line at the bottom reminiscent of the old illustrated stories with the relevant quote at the bottom of each piece. I riffle through the pages on my way to the front of the book and catch full pages of art, the icons that are slowly becoming familiar, and a clean layout. Only then do I go to the front page and work my way forward. I read the prefatory information. I wonder if Nash is Paul’s son, or a dear friend, or a mentor of some sort. Then I get to the table of contents. I’m on the second page of it when I realize, wait, that’s no table of contents. It’s an index! Where the table of contents should be! I flip to the end and confirm there is no additional index there. I flip through the book again and see that there are no chapters or titled sections. It’s a clever idea, putting the index in the front, given that structure. You can’t have a table of contents when there are no headings. And why not use the index as a kind of orienting device for the reader. Flipping through the index, I see that the main organization elements are minotaurs, society and culture, the jungle, and the means of play. By this point I’m eager to get to the main text, so I breeze past the index and start at page 15. So what’s your ritual, if you have one? And of course, I’m handling the physical book. Those of you reading an electronic version, is there a ritual you engage in, of do you just start at the beginning? I was going to read something from the 1970s next, but since this just showed up in my mailbox yesterday, I think I'll read The Clay that Woke next.

If you are one of the many who took advantage of +Paul Czege's moving sale, or if you've had the text for some time and not read it, I officially invite you to join me! ETA: If you want to join in, use #claytalk in your posts. #Claytalk continues with a look at play advice in The Clay that Woke.

(My last #claytalk post is here, if you’re interested: https://plus.google.com/102721916927145169256/posts/W1jRsDenCdS) RPGs are somewhat unique in the world of tabletop games insofar as there is usually a layer of instruction beyond the rules of the game themselves that guide players in how to approach the game to get the most out of the experience. It is somewhat analogous to strategy tips in competitive games that tell players how to think about the game to increase their chances at succeeding. Only, succeeding in an RPG means having a particular play experience that the game is designed to create. This play experience is related to but different from what you are playing to find out. In The Clay that Woke we are told that we are playing “until it’s clear whether the watchers will frondesce and bloom again for society’s entrance into a new age of greatness or not” (22). Players are also told that they will “try to uphold the difficult, stoic minotaur philosophy of silence” and “earn a name” (16). Those goal posts tell us about the larger narrative that will unfold through play and the smaller play goals that get us there. What I want to look at instead is the particular philosophy of roleplaying that underpins the playing the gets us to those goals. In The Clay that Woke, Czege lays out his particular philosophy through the parable of the Chimera and the Gargoyle: “[T]he Gargoyle is a moment in time, a fabricated thing. It fights time for its existence. The Chimera is time. The beasts come together as an expression of shared self-imagination, self-realization, heterogeneous but gloriously, committedly permeable throughout. The beasts test and prove the identities of one another, penetrate and define each other. And the secret is we can all do this. We can bring into existence a shared self that expresses more about ourselves than any of us could say individually. It is a triumph of becoming time. Consider the Gargoyle and the Chimera. The Gargoyle is a made thing that fights time for its legacy. It must be perfect to even exist. We aspire to its perfect fabrication, but we cannot achieve its lofty, impossible perfection. The Chimera brings itself into existence and has no shame for its imperfection. At any given moment in time the Chimera is a triumph. Its imperfections are throughout its existence, and throughout time before and after, and not within any moment of its triumph. You might say the Gargoyle is an artifact of a triumph, and the Chimera is the anecdote of its triumph” (97). We are told on the following page that “[t]he goat, the lion, the snake, and the flames [that merge to form the Chimera] are like a group of roleplayers coming together to play The Clay that Woke” (98). The power of the Chimera, the power of roleplaying, is in the “com[ing] together as an expression of shared self-imagination, self-realization.” Whereas the gargoyle is a thing complete and unchanging, the Chimera is the process of discovery. Specifically, what is discovered is about the players who have come together to roleplay. While the process of playing The Clay that Woke reveals things about the world of the narrative and the minotaurs and gamemaster characters we play, the true act of discovery is of what’s within us, according to this passage. As Czege says, “Your starting minotaur character seems undefined, but he’s really not, because you the player are present within him, just the way the essences of goat, lion, snake, and flames are present in their play among the jungle slurry of history and culture. Your interests drive his actions” (98). Character creation is rather sparse in the game. The character sheet tells you what tokens you begin with and what actions your character can take to refresh their various tokens, but there is nothing on the character sheet that makes your character unique. The character sheet gives you an archetype, and who your minotaur is is discovered only through play, and according to the parable of the Chimera and the Gargoyle, that discovery necessarily involves revealing something about yourself, the player. You’ll notice there are no background establishing questions or ways to define how one minotaur character is related to another character on the sheets or any part of character creation. The game is not interested in creating and character full of charged connections and backgrounds the way a lot of currently popular RPG’s manage character creation. As the text says, the game “isn’t about unwinding drama from a made snarl of inter-character stress” (98). Instead, your minotaur character begins as a seemingly clean slate so that you don’t distance yourself from your character with all these fictional features. The game wants you the player to be “present within him” and your the player’s interests to “drive his action.” Only by doing so can the process of play be a tool for “self-realization.” And play is not just a process of self-discovery as an individual, but about the greater discovery that can be achieved by everyone at the table roleplaying together. The game is “about submitting to the mechanics of an alien world and engaging a primordial ability to communicate across the boundaries of your human differences with other players to find progressively the mutual incitement of your essences” (98). Damn. That’s a lofty and beautiful expression of the end goal of a successful session of roleplaying The Clay that Woke. Just give yourself over to the mechanics of the game and the fictional setting of the world and we’ll be able to reach out beyond ourselves to a true connection with each other that will “incite[]” our “essences.” “Submitting” seems like a key word in that sentence. You cannot fight the system. We are told not to “hack[] together a narrative within some defined story structure” (98). Let what happens happen and don’t work towards a story, and that goes for the minotaur players as much as for the GM. Players are warned not to “come to the game as a player with a goal of authoring a drama with your minotaur . . . . Come to it to discover your minotaur in the context of the game” (107). Play is first and foremost an act of discovery (of both the character and yourself), not the creation of an authored drama. That authored drama is the Gargoyle, dead and perfect, not the Chimera, living and an expression of shared self-imagination. Further advice: “If your scenes don’t seem fun, try to make gamemaster characters important by the things your character does” (107-108). That, to me, is the surprising bit of advice that sent me back to the instruction to submit. We are used to playing characters who are the center of the stories that unfold, and it many other games, I have read instructions for the GM not to get caught up in their own NPCs, to remember that the game is about the PCs. Yet here is an instruction to the players to use their characters to make the gamemaster characters important! This importance of submission is directly related to the minotaur characters being second-class citizens in the Degringolade. You play menial laborers whose rights in the city are never made clear. At times you seem like laborers and at other times like slave labor. There is the story in the book about the duel two minotaurs fight on behalf of their “psychotic employers” (88), but the minotaurs only just met the men in the jungle and were drafted into service to fight a duel to, potentially, the death. Truly free members of the society could have told the two men to go fuck themselves. In this context, it becomes clear that “employer” is a kind of euphemism. Minotaurs must submit to their social situation. To not do so is to break silence. And as the minotaurs must submit, the game wants the players to submit. The advice the GM gives to the creation of situations in which the minotaurs are placed focuses entirely on the interests and observations of the GM. The situations are created without thought about who the minotaurs might be or which character plays which minotaur. The minotaurs themselves, at least at the start of the game, are completely interchangeable, and any minotaur can be assigned to any employment opportunity. There is some allowance made for the archetypes of the minotaurs in play, but that’s where the consideration ends. This is not to say that the GM is like the human masters and the players like the minotaurs. The GM and players are clearly working together through play on the path of discovery - discovery of the world, the unfolding story, the characters at play, and the players themselves. I was saying to Slade Stolar in the comment sections to my last post that I was surprised that the GM section of the text didn’t give explicit commands to the GM to push at the boundaries at which the minotaurs would and would not break silence. Having reread that portion of the book, I see now that such a stance in unnaturally aggressive to meet the author’s end. The text tells the GM to create situations born out of their personal irritations and experiences with their culture and society, translated to fit the Degringolade. Then you place the minotaur characters in a position to be a part of that situation, receiving requests and commands from the gamemaster characters. In responding to the situation, the character may or may not break silence; the game doesn’t really care. The strictures of silence put productive boundaries on the behavior of the PC and hardwire inner tensions into the minotaur characters very existence to ensure that whatever response they have will necessarily be thoughtful and interesting. A lot of important features of The Clay that Woke run contrary to the way a lot of other RPGs are run. Let’s take Apocalypse World and games that are inspired by it. Those games set up a “snarl of inter-character stress” from the first session and then let the players drive the action of the game, with the MC playing the world responding to those actions. The unfolding narrative centers on the PCs, and the NPCs are there to play against the PCs to show off how awesome they are. In The Clay that Woke, it is the doings of the gamemaster characters that drive play, even as the individual minotaur characters’ actions are driven by the players’ interests. The PCs are responding to the actions of the gamemaster characters rather than the other way around. Certainly, once things are in motion, everyone is responding to each other, but the focus is on the doings of the gamemaster characters. Czege even warns the GM that players “are often noncommittal in their early interactions, and also often interpret silence as calling for disinterest or outright rejection of the doings of gamemaster characters, so you’ll have to work a bit and use various methods to provoke them to get involved” (123). That puts a lot of the initial onus on the GM, but once things get moving, once situations are established and the minotaur characters are invested in the goings on of their human employers, I imagine the game moves along smoothly and creates fascinating moments. There is more to say, but at the moment I have neither the time nor the energy. If I were to go on, I would look at the role of the jungle in the game, as compared to the city. The city is where the GM prepares social and culture problems for the characters to explore, but preparation for the jungle is much lighter, involving the Voices and a few exciting encounters covering all four inflection types. I would want to explore the language of the game, especially words like “inflection,” “intrinisic,” “Voices,” and “externals.” I would want to explore the Krater and the unique nature of tokens as bids on possible outcomes rather than economic unit that can be spent to achieve a desired outcome (and the unique exception of name tokens being spent that in the one condition that allows it). So much to discuss and so little time. If you discuss any of these things, I hope you tag me so I can be sure to read it. Fun fact:

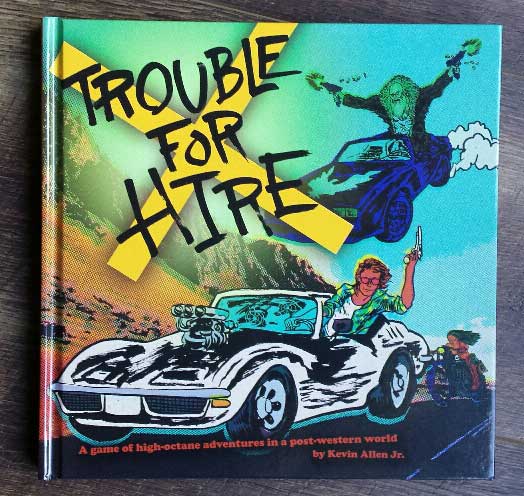

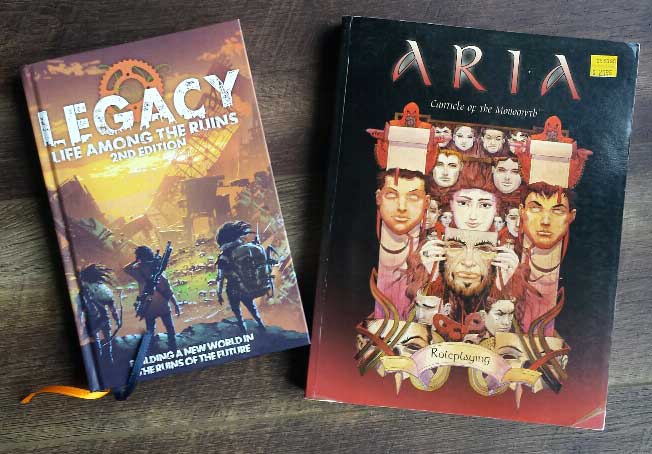

"First and foremost, Jared Sorensen believes in game design as art. It comes across in the bizarre, innovative, and beautiful ideas embedded in his designs, but it also comes across in the surprising fact that he not only didn't playtest many of his earliest designs - but he didn't even play them. As of 2008, he never played his first professional design, Schism; he similarly didn't play his popular Lacuna Part I for years." -Shannon Appelcline, Designers & Dragons: The 'OOs, page153. Something old, something new! Two RPG texts arrived in the mail this week, both having the unique feature of being able to play zoomed in as individuals or zoomed out as houses or factions. I love it when the post gets unexpectedly thematic!

Legacy is a gorgeous text in both its layout and its art. Excited to read both of them! From the DC Heroes "Powers & Skills" book:

"Superspeed gives a character the ability to move . . . at speeds faster than humanly possible. . . . "At [a score of] 30 . . . or more, the character may Time Travel. With a speed of 30 APs [the standard unit of measure in the game] or more, a character may travel to any time period, either past or future. He may not change what occurs - he many only observe." Wow. I know comic books have used the time-travel-through-speed thing before, but I didn't expect a game to say, Sure, do it. I pity the GM whose player uses The Flash, say, to time jump all around whipping up some real Bill-and-Ted's shenanigans. And by what law of time travel do they figure characters can only observe other time periods? Is the speedster not actually there? Is it just a rule to keep things from becoming too messy? If so, why allow for time travel at all? This seems like a poorly thought-out thing all around. DC Heroes takes killing very seriously. A Player has to deliberately enter "killing combat" to kill or be killed, and if they do, "this Player loses any Hero Point awards he might have gained." Yeah, no experience for that play session at all, that's the penalty. Moreover, the rules add this:

"NOTE: Players who consistently forfeit [Hero Points because they entered into killing combat] may not be asked by the GM to participate in any further adventures." Once or twice because the fiction demands it? Go ahead and make that call, but you get no Hero Points. Do it regularly? You are probably not welcome here. (Marvel Super Heroes is similarly constructed. There a character loses all her Karma points if she "kills someone or takes no action to prevent the death of an innocent person that [s]he could have saved." But the Karma system is much more interesting and complicated, with a whole list of things that add or subtract Karma. The game however never says you can't commit crimes or become a villain, only that you'll be punished with bad karma. DC Heroes goes much further in stating that the GM has every reason to boot your ass from the game.) "*Gymnastics* allows the character to perform rolls, tumbles, flips, etc. It also allows the character to juggle. . . .

"Each item juggled more than 3 is +1 to the Opposing Value (normally 0), so 5 items will have an Opposing Value of 2. The GM may increase the Opposing Value if the items are of different balances and weights. For example, juggling bowling balls and toothbrushes would be worth +2 to the Opposing Value. The Resistance Value is the same as the Opposing Value. The RAPs are the amount of time the items may be juggled without dropping one." - from DC Heroes "Powers and Skills," page 29 Remember when Batman had to juggle bowling balls and toothbrushes for at least 5 minutes in order to save Gotham? I can't help but wonder what happened during early play of this game that led the authors to have to decide where juggling fit into the skill trees and how it should work mechanically. Is there a juggling theme running through DC comics that I'm unaware of? Not a lot of RPG texts instruct the players to tell the GM to fuck off, especially not ones published in 1985. There is a moment in the DC Heroes Player's Manual that lets the players know that they can tell the GM no:

"Subplots should be fun, not morbid or cruel. If you don't like the way the GM is running your Subplot or if you are just bored with it, just 'pull the plug' and refuse to accept the GM's judgement. You cannot use this rule to change what has happened in past gaming sessions, but any Subplot event that has just happened can be negated. "For instance: The GM announces that your girlfriend is murdered by the villain. If you feel this is too much and no fun to play, simply say that you refuse to accept this event." Here's my review of Sandman: Map of Halaal:

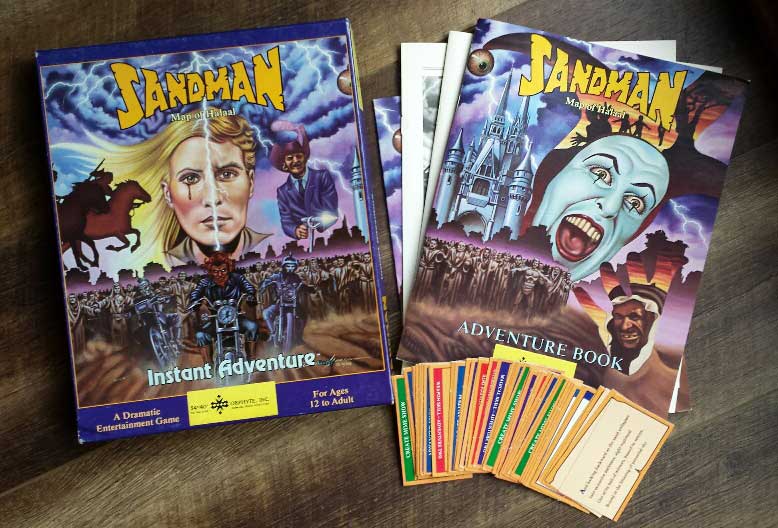

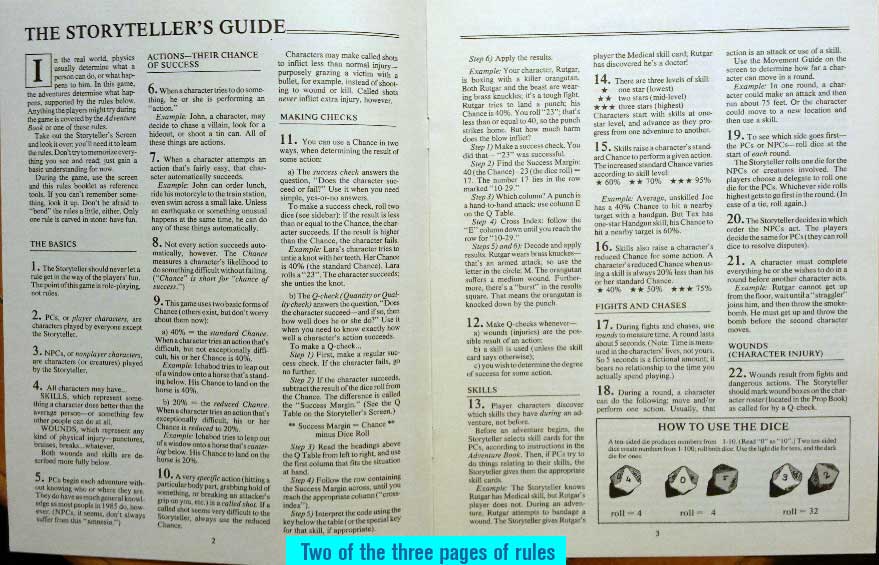

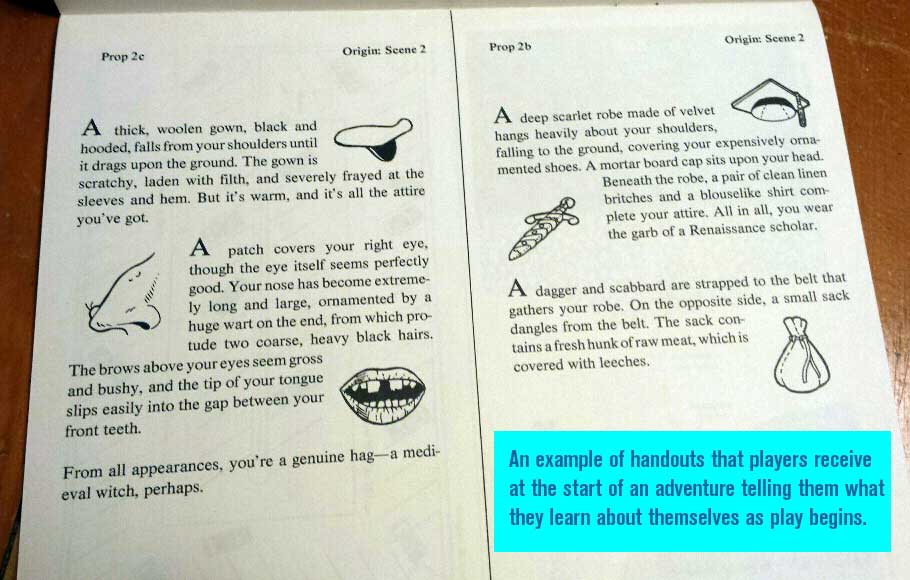

Pacesetter published Sandman: Map of Halaal as a box set in the summer of 1985. In the introductory pamphlet, the designer talk about their design goals for the game, distinguishing Sandman from the games that came before it. The root difference, they say, is that other RPGs inherited their attention to simulated reality from their wargaming roots, and that adherence to simulated reality creates a thick pile of rules to cover every contingency. This thick set of rules makes jumping in and playing quickly an impossibility, it tangles up play in rules rather than in drama, and it makes prep time to run a game as long as game play itself. Sandman: Map of Halaal seeks instead to create a game that has a handful of rules that let players focus on the dramatic story, play with a minimum amount of prep, and get from the unboxing to the playing of the game in as much time as it would take to unbox and play a boardgame. To this end, there is no rulebook. There is instead an introductory pamphlet with a mere 3 pages of the rules. The rules are numbered from 1 to 29 and grouped into sections: “The Basics,” “Actions – Their Chance of Success,” “Making Checks,” “Skills,” “Fights and Chases,” and “Wounds (Character Injury)”. Boom. Five minutes in and you have all the rules laid out neatly for you. So what about the adventure? What about character creation? How can you start playing without any of that stuff? The solutions are clever, and of course they come with their own problems and advantages. First, characters. There are no character sheets. In the first adventure, characters begin by waking up on a passenger train, and judging by their clothes they are some time in the 1940s. See that? No character sheet needed because you are a blank slate. The game’s setting makes this amnesia conceit more than a cheap trick: the player characters are adrift in a surrealist dreamscape, hunted to some extent by a mysterious figure called “The Sandman.” In this setting, each adventure can begin with the characters in media res on their journey. Each adventure has a wildly different dreamscape, some realistic and others bizarre and haunting. In some adventures magic is common and in others it’s not. It means that the players never know what they’ll be getting when the adventure starts, and no matter who you were in the last adventure, you’re somebody else in the current one. Character skills are discovered through play. If you kneel to look at an injured man’s wounds, you might discover that you are versed in medicine. At that point, the GM hands you a card that describes your skill and how to use it mechanically. If your character survives the adventure, you keep the skill cards for use in the next adventure. Your character’s abilities are tracked over time by your stack of skill cards. It’s a pretty clever way to avoid having pages and pages of skills, and each new set of adventures (Pacesetter planned for the “series [to] consist of several more boxed sets (up to six), plus one final edition”) can include whatever skills are relevant to those particular adventures. The system keeps the cognitive load low for all the players. As for the GM, she is given as little to read in advance about the adventures as possible while still giving her enough information to do her job. It’s a delicate balancing act. All she has to read before starting the adventure is a brief summary of the overall adventure plot. To help the GM keep this overarching story in mind, the game comes with a one-page pictogram of the overall story that the GM can pin to her GM screen to see the course of the things at a glance. There are actually a lot of drawings in the GM’s adventure book, a clever way to communicate a lot of information at a glance. Each adventure is divided into 3 or 4 Acts, and each Act is preceded by a quick summary of what will happen in the act. So, after the group reads the 29 rules, the GM reads the adventure’s summary, pins the pictogram to her GM screen (which helpfully has the 29 rules reprinted there), reads the Act 1 summary, and gets the game underway. It is a minimal time from start to play. There are many prices that get paid for this speed, of course. The adventures allow for very little wiggle room from the player characters, and all of their choices have very little impact on the story that unfolds. The GM, called “The Storyteller” in the game, is told to let PCs wander and do what they want, but to make sure that all of that wandering has no impact on the story: “For example, what if one PC decides to search for a cure for his amnesia while his friends continue the main story? You might handle the main story for a while, putting the stray PC on ‘hold’ until you think of what to do. Then you could make up a minor NPC – a psychiatrist, perhaps – who tries to cure the stray PC’s amnesia. Of course, the psychiatrist fails; creating a past for the PC would be incompatible with the adventure and the game. After letting the stray player try this ‘goose chase,’ you should encourage him to join the others.” Of course the psychiatrist fails. Usually the price for refusal to follow the plot is character death. Here’s an excerpt from the first adventure of what the rules say to do if the PCs do not agree to help the French resistance: “The PCs are later killed in their sleep by members of the French resistance. The adventure has ended.” Yeah, you can play this out the way it wants to go, or we can pack it all in and start the next adventure instead. The root of this problem is of course that the game needs to be something the GM can read pre-written passages for nearly any occasion. In a lot of ways, the game is like a 1980s computer RPG, with the GM acting as the computer. The GM reads the scene-setting passage, and then has prompts for what to read if the characters do X or talk to Y. The human GM is more flexible than the computer, but in the end, players play this game for the same reason they play a computer RPG, to be entertained by the story while playing a small part in the specifics of how it unfolds. With this approach, the game is exactly as fun as the adventure is interesting and intriguing. Thankfully for Sandman, that’s what the game does exceedingly well. As I mentioned earlier, Sandman: Map of Halaal is only the first chapter of a larger metaplot, a mystery stretching over the many releases. One of the promotional tricks that Pacesetter used to market the game is that they offered $10,000 to the first player who could solve the mystery of who the PCs are and who the Sandman is. Who is this Sandman who keeps appearing and trying to kill you? How are these worlds related? Is that character or the way she’s behaving a clue to what this is all about? The adventures have a cumulative effect as each one teases the players (or the reader, in my case here) with crumbs of information. The authors handle the dream-like qualities incredibly well, finding motifs and themes and providing evocative characters with strange behaviors. Things that appear in the first adventure of the book come around full circle in the final adventure of the book in a way that lets you know that something big is building—and it does so in what I found to be a very satisfying manner. Sadly, the following adventures never materialized, so all we have is this one book. While the adventures themselves have an occasional puzzle, taken as a whole they are one big puzzle, and that is what the players are playing to find out. Each adventure ends with a poem fragment, a clue to the larger mystery, so the players want to make sure their characters survive the adventure and get all the clues they can. If you are playing to explore your character or their interpersonal relationships, you are going to have an uphill battle and find yourself especially frustrated. If you are using your characters as tools to interact with the fiction to solve the mysteries great and small, you’ll enjoy yourself just fine. Nothing you do can really affect the fiction; it can only keep you alive or get you killed, bring you answers to the mystery or shut you out. I haven’t run the game, and I didn’t get the game with the intention of ever playing it. Nevertheless, part of me would really like to bring it to the table in order to see how players either butt up against the limits or dig into the mystery. The mechanics are rather rudimentary and often pointless given that the story will get there no matter what the outcome is. Still, I would like to see how giving the GM could be while maintaining the integrity of the adventures as written. I think I’ll be able to talk my family into it as some point, and if I do, I’ll add an addendum to his review. I got the game because James Wallis and Jason Morningstar had a brief exchange on dice.camp about how cool they thought the game was in their youth and how it has left a lasting impression on their aesthetics. I got the game because Shannon Appelcline’s described it as an innovative attempt to create an RPG that can be pulled out and played as quickly as one might pull out and play a board game. I’m really glad I read it because it has given me a lot to think about and admire in its construction. The skill cards are a neat idea. The way the game tracks wounds is simple and cool. The way the game introduces rules and complications within an adventure to control cognitive load is smart. But my favorite takeaway is the way the game treats its surrealist subject. There are images and thematic echoes that hit just the right notes. I am fascinated by surrealism, but I find it very hard to create in RPGs in a way that is effective and resonant. I think this game might have some answers for me. That’s what I’ll be meditating on in the long run, I think. " If PCs Still Refuse to Help : De Vries leaves. The PCs are later killed in their sleep by members of the French resistance. The adventure has ended."

- from, Sandman: Map of Halaal, "Adventure One: The Sandman Comes" Ouch. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed