|

Here's my review of Sandman: Map of Halaal:

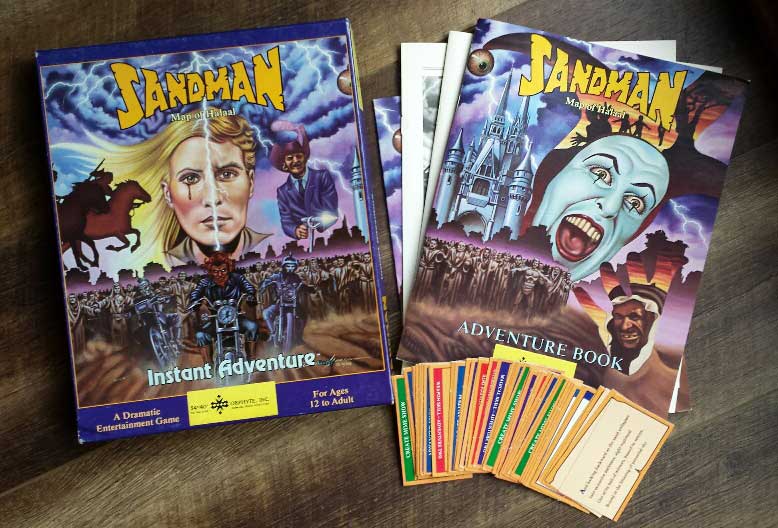

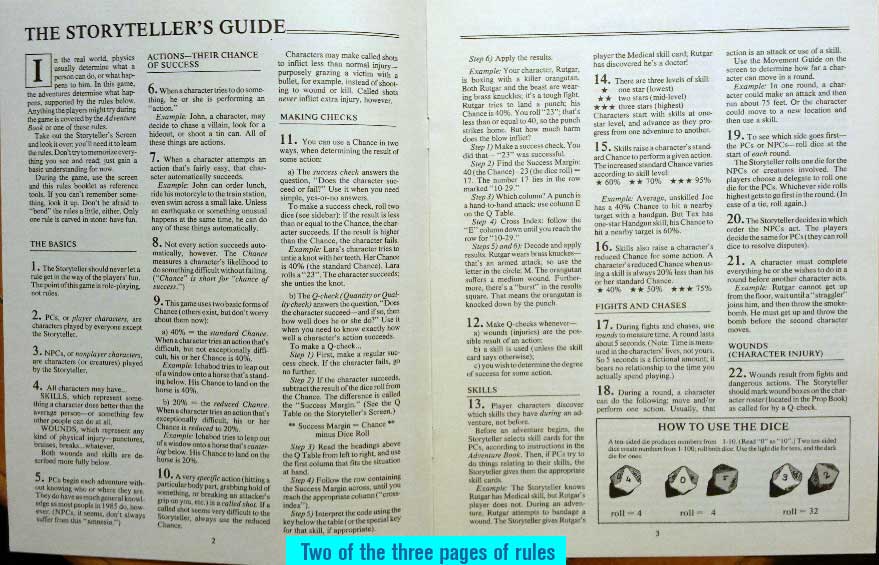

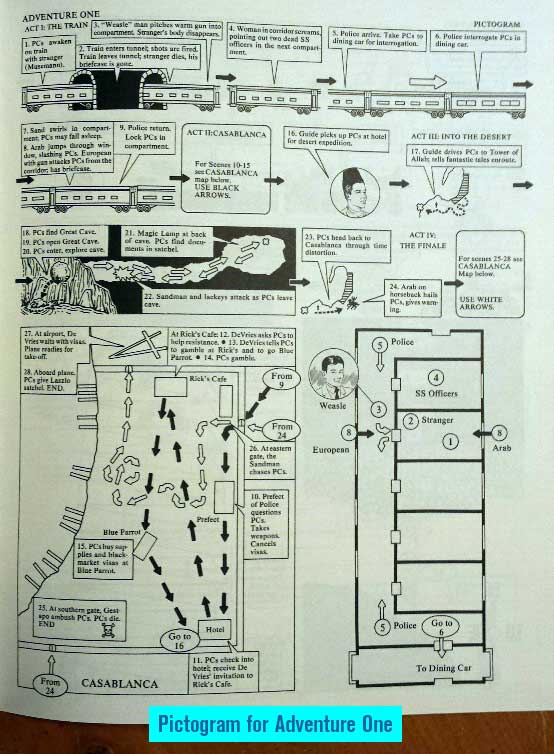

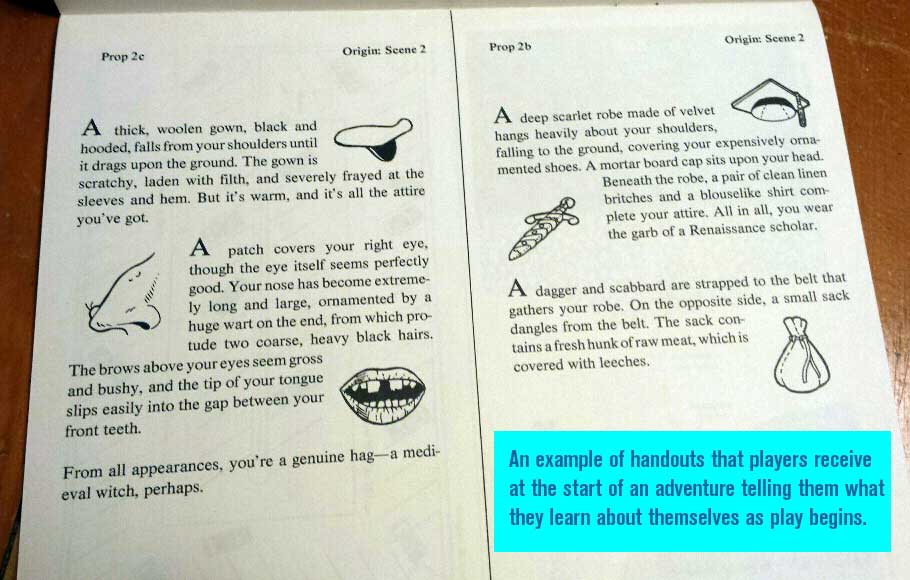

Pacesetter published Sandman: Map of Halaal as a box set in the summer of 1985. In the introductory pamphlet, the designer talk about their design goals for the game, distinguishing Sandman from the games that came before it. The root difference, they say, is that other RPGs inherited their attention to simulated reality from their wargaming roots, and that adherence to simulated reality creates a thick pile of rules to cover every contingency. This thick set of rules makes jumping in and playing quickly an impossibility, it tangles up play in rules rather than in drama, and it makes prep time to run a game as long as game play itself. Sandman: Map of Halaal seeks instead to create a game that has a handful of rules that let players focus on the dramatic story, play with a minimum amount of prep, and get from the unboxing to the playing of the game in as much time as it would take to unbox and play a boardgame. To this end, there is no rulebook. There is instead an introductory pamphlet with a mere 3 pages of the rules. The rules are numbered from 1 to 29 and grouped into sections: “The Basics,” “Actions – Their Chance of Success,” “Making Checks,” “Skills,” “Fights and Chases,” and “Wounds (Character Injury)”. Boom. Five minutes in and you have all the rules laid out neatly for you. So what about the adventure? What about character creation? How can you start playing without any of that stuff? The solutions are clever, and of course they come with their own problems and advantages. First, characters. There are no character sheets. In the first adventure, characters begin by waking up on a passenger train, and judging by their clothes they are some time in the 1940s. See that? No character sheet needed because you are a blank slate. The game’s setting makes this amnesia conceit more than a cheap trick: the player characters are adrift in a surrealist dreamscape, hunted to some extent by a mysterious figure called “The Sandman.” In this setting, each adventure can begin with the characters in media res on their journey. Each adventure has a wildly different dreamscape, some realistic and others bizarre and haunting. In some adventures magic is common and in others it’s not. It means that the players never know what they’ll be getting when the adventure starts, and no matter who you were in the last adventure, you’re somebody else in the current one. Character skills are discovered through play. If you kneel to look at an injured man’s wounds, you might discover that you are versed in medicine. At that point, the GM hands you a card that describes your skill and how to use it mechanically. If your character survives the adventure, you keep the skill cards for use in the next adventure. Your character’s abilities are tracked over time by your stack of skill cards. It’s a pretty clever way to avoid having pages and pages of skills, and each new set of adventures (Pacesetter planned for the “series [to] consist of several more boxed sets (up to six), plus one final edition”) can include whatever skills are relevant to those particular adventures. The system keeps the cognitive load low for all the players. As for the GM, she is given as little to read in advance about the adventures as possible while still giving her enough information to do her job. It’s a delicate balancing act. All she has to read before starting the adventure is a brief summary of the overall adventure plot. To help the GM keep this overarching story in mind, the game comes with a one-page pictogram of the overall story that the GM can pin to her GM screen to see the course of the things at a glance. There are actually a lot of drawings in the GM’s adventure book, a clever way to communicate a lot of information at a glance. Each adventure is divided into 3 or 4 Acts, and each Act is preceded by a quick summary of what will happen in the act. So, after the group reads the 29 rules, the GM reads the adventure’s summary, pins the pictogram to her GM screen (which helpfully has the 29 rules reprinted there), reads the Act 1 summary, and gets the game underway. It is a minimal time from start to play. There are many prices that get paid for this speed, of course. The adventures allow for very little wiggle room from the player characters, and all of their choices have very little impact on the story that unfolds. The GM, called “The Storyteller” in the game, is told to let PCs wander and do what they want, but to make sure that all of that wandering has no impact on the story: “For example, what if one PC decides to search for a cure for his amnesia while his friends continue the main story? You might handle the main story for a while, putting the stray PC on ‘hold’ until you think of what to do. Then you could make up a minor NPC – a psychiatrist, perhaps – who tries to cure the stray PC’s amnesia. Of course, the psychiatrist fails; creating a past for the PC would be incompatible with the adventure and the game. After letting the stray player try this ‘goose chase,’ you should encourage him to join the others.” Of course the psychiatrist fails. Usually the price for refusal to follow the plot is character death. Here’s an excerpt from the first adventure of what the rules say to do if the PCs do not agree to help the French resistance: “The PCs are later killed in their sleep by members of the French resistance. The adventure has ended.” Yeah, you can play this out the way it wants to go, or we can pack it all in and start the next adventure instead. The root of this problem is of course that the game needs to be something the GM can read pre-written passages for nearly any occasion. In a lot of ways, the game is like a 1980s computer RPG, with the GM acting as the computer. The GM reads the scene-setting passage, and then has prompts for what to read if the characters do X or talk to Y. The human GM is more flexible than the computer, but in the end, players play this game for the same reason they play a computer RPG, to be entertained by the story while playing a small part in the specifics of how it unfolds. With this approach, the game is exactly as fun as the adventure is interesting and intriguing. Thankfully for Sandman, that’s what the game does exceedingly well. As I mentioned earlier, Sandman: Map of Halaal is only the first chapter of a larger metaplot, a mystery stretching over the many releases. One of the promotional tricks that Pacesetter used to market the game is that they offered $10,000 to the first player who could solve the mystery of who the PCs are and who the Sandman is. Who is this Sandman who keeps appearing and trying to kill you? How are these worlds related? Is that character or the way she’s behaving a clue to what this is all about? The adventures have a cumulative effect as each one teases the players (or the reader, in my case here) with crumbs of information. The authors handle the dream-like qualities incredibly well, finding motifs and themes and providing evocative characters with strange behaviors. Things that appear in the first adventure of the book come around full circle in the final adventure of the book in a way that lets you know that something big is building—and it does so in what I found to be a very satisfying manner. Sadly, the following adventures never materialized, so all we have is this one book. While the adventures themselves have an occasional puzzle, taken as a whole they are one big puzzle, and that is what the players are playing to find out. Each adventure ends with a poem fragment, a clue to the larger mystery, so the players want to make sure their characters survive the adventure and get all the clues they can. If you are playing to explore your character or their interpersonal relationships, you are going to have an uphill battle and find yourself especially frustrated. If you are using your characters as tools to interact with the fiction to solve the mysteries great and small, you’ll enjoy yourself just fine. Nothing you do can really affect the fiction; it can only keep you alive or get you killed, bring you answers to the mystery or shut you out. I haven’t run the game, and I didn’t get the game with the intention of ever playing it. Nevertheless, part of me would really like to bring it to the table in order to see how players either butt up against the limits or dig into the mystery. The mechanics are rather rudimentary and often pointless given that the story will get there no matter what the outcome is. Still, I would like to see how giving the GM could be while maintaining the integrity of the adventures as written. I think I’ll be able to talk my family into it as some point, and if I do, I’ll add an addendum to his review. I got the game because James Wallis and Jason Morningstar had a brief exchange on dice.camp about how cool they thought the game was in their youth and how it has left a lasting impression on their aesthetics. I got the game because Shannon Appelcline’s described it as an innovative attempt to create an RPG that can be pulled out and played as quickly as one might pull out and play a board game. I’m really glad I read it because it has given me a lot to think about and admire in its construction. The skill cards are a neat idea. The way the game tracks wounds is simple and cool. The way the game introduces rules and complications within an adventure to control cognitive load is smart. But my favorite takeaway is the way the game treats its surrealist subject. There are images and thematic echoes that hit just the right notes. I am fascinated by surrealism, but I find it very hard to create in RPGs in a way that is effective and resonant. I think this game might have some answers for me. That’s what I’ll be meditating on in the long run, I think.

1 Comment

CreamOweeT

12/25/2021 04:01:14 pm

I just read this article after buying a complete "unused" copy of Sandman Map of Halal. Very informative! I'm super excited to dive into this. I appreciate the author and the effort that went into being so thorough. Thank you!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed