|

This is the best full-length RPG text I have read in a long time, since maybe Paul Czege's The Clay that Woke. It's not an easy manual to read in terms of trying to understand game play, but it has so much to offer, that I don't mind its difficulties at all.

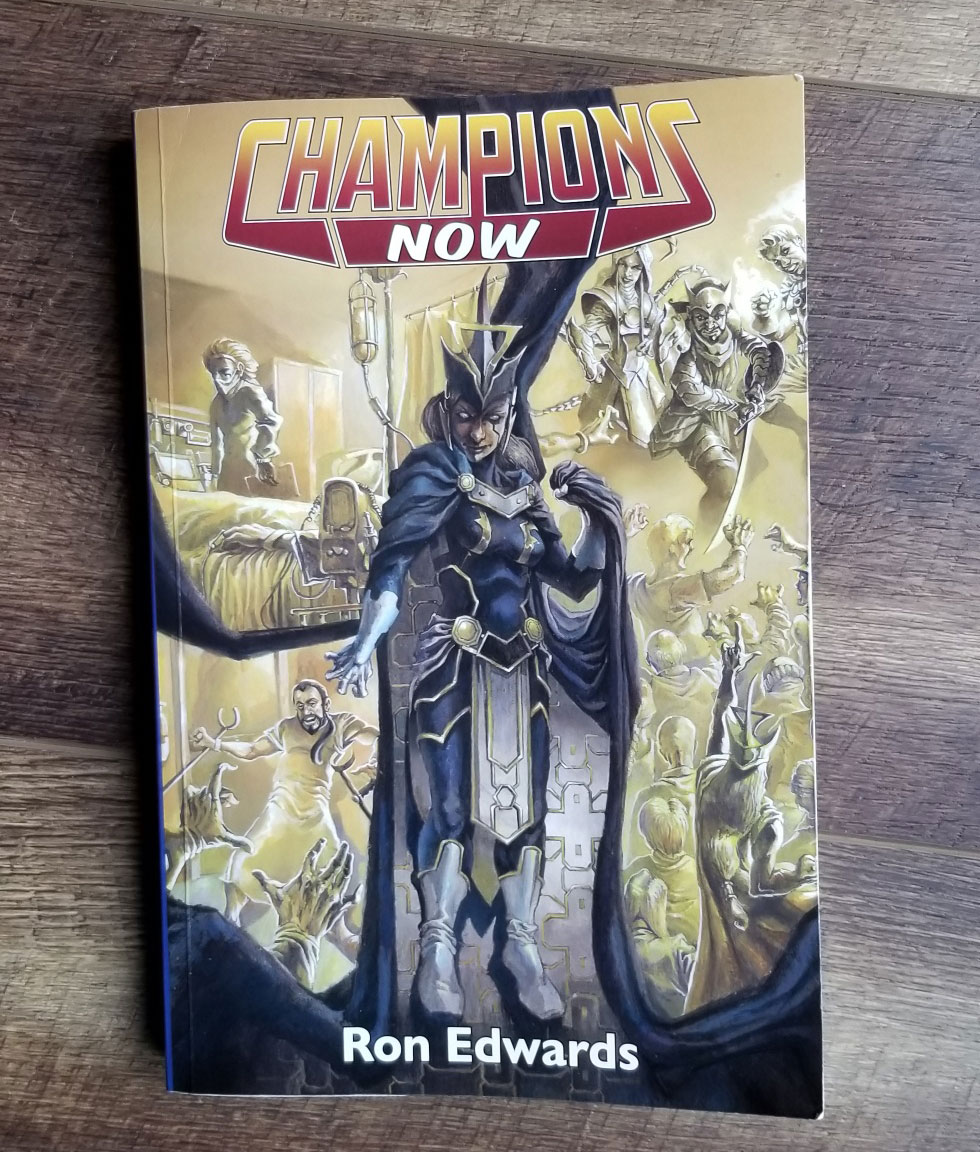

Before I go into details, let me state first that I have not played the game, only read the text twice. These thoughts are not about actual gameplay but about the text itself and the way I understand the mechanics from that reading. Take this evaluation for what that's worth. I was excited about getting to read Champions Now for a number of reasons. First, the second edition of Champions was the first RPG I spent my own money on. My older brother had brought D&D and Traveller into the house, but Champions was mine. Sadly, I was only 10 years old and couldn't figure out how to run the game or find anyone to run the game with, so I was stuck building characters and having an occasional battle between them. Given that history, I was excited to see what Ron Edwards would bring to the game. He had stated that the first generation of Champions games, editions 1-3, were his favorite, and I knew that this edition was his own rendition of what that game would evolve into if they were guided by his own thoughts. And I'm quite fond of the way Edwards thinks; even when I'm not in full agreement with him, I always enjoy his perspective and insight. Edwards is a good writer, but I always find that I need to approach his texts slowly and with patience for two reasons. First, there is a lot of thought behind each sentence to the point that, to employ an overused metaphor, each sentence is the tip of the iceberg of his thought. Second, Ron does not like to repeat himself, so you only get that one chance to understand his meaning. This book lived up to those expectations. What makes Edwards's books such excellent reading is not only his writing skills but his analytical and research skills as well as his total conviction in the conclusions he draws. Everything about Champions Now is drawn from his thorough knowledge about comic books and their history, specifically the comic books of the 70s. Other superhero games focus on superheroes across media and time, as a genre. But in Champions Now, Edwards is interested in the way superhero comic books were made in the oversightless days before superheroes and their stories were controlled by corporate interests and creativity-choking generic conventions that make everything safe and consumable. As he says: "For three or four decades more, as the corporatism gelled and its lowering gaze turned more attentively toward the little pamphlets [i.e. comic books], creators dodged subordination here and there, but less and less. As of the 1990s, the paper no longer smelled bad, and that was the beginning of the end. "By the 2010's the ultimate villain Doctor Franchise has won. The comics are engineered adjuncts for other media, a clever way for customers to pay for the advertising, like buying t-shirts with logos on them. Although a movie can be a good movie and a TV/Netflix show can be a good show, their superheroes are solid commercial fare, with no garbage and no diamonds. They are comfortably dramatic, broadly enjoyable, intelligently reminiscent or deconstructive - and nothing more. They have suffered the inescapable death of legitimacy" (5). That passage is a great example of both his conviction and his writing. If you follow Edwards work, you already know that he prefers garbage with diamonds in it to anything reliably good. Diamonds really only appear in garbage, where mistakes can be made and brilliant ideas are allowed to bubble forth. And that's his guiding principle in constructing Champions Now. If you run your game following his rules and your own taste, free from genre and pre-constructed plot points, you will have not only a solid game, but these amazing moments of creativity and originality that lift your game experience far above what you could get otherwise. The rules themselves are exciting. Before you get to any character building, you have the two guiding statements. You, the person who is planning on gathering people together and GMing them through some series of sessions, begin by creating two statements about the game you are going to play. There is no special setting for the game, and you are assumed to be setting your game in the world as it is today, just as the comic books that inspired the game were set in the concurrent world. Similarly, there is no set genre, mood, or tone for the game. So your two statements become the guiding aesthetic principles that anchors all the players to the same rough vision. Your first sentence is "one solid bit of content about superpowers, heroes, or villains," and the second is "one solid bit of fictional style and specific types of problems" (32), along with a city or location in the real world. So to give an example from the book, the guiding statements might be: A superhero stands for something and means it, and you got your family in politics; you got your politics in my family, set in Hartford, Connecticut. Another example from the book is, powers require effort, pain, practice, sacrifice, and dedication, coupled with military life and careers in Portland, Oregon. These statements are your responsibility, and then the other players take them and create their heroes. They don't need to run anything by you in creating the heroes as they are guided by the two statements, free to make their own interpretation as they please. This is an incredibly simple tool that has ramifications throughout the rest of the game. It becomes a constant touchstone as the villains, in opposition to the heroes, are tied to those statements, perhaps challenging them, twisting them, or taking them to their logical extremes. And since all players get to express their own interpretation of the statements through their characters--both in their creation and in the way they are played--everyone's creative energy is channeled through the statements, even as they tug at and play with the other visions. The other great thing about creating such statements is that it demands that the GM has some “take” on the game about to be played. If you as the GM can't find two statements your excited about, then you probably shouldn't be running the game, because you won't have the excitement and personal interest to make it all hum. This is a first-rate bit of tech. The powers themselves are a list of basic powers with additional lists of advantageous and limiting modifications so that you can build any power to work in whatever way you want. More importantly, the fiction you create surrounding those powers is inviolable, so you can describe it in whatever way you want, regardless of the way you constructed the power. In later versions of Champions, once it was made to be a part of the Hero System, powers and the system became the main focus so that everything in our world could be built by those power definitions, and if you could build it right, it would be that thing. Ron wants none of that. In Champions Now, the fiction is always the thing itself, and the powers are merely the mechanical teeth that let the fiction grip the dice. As he explains it, using the concealment power, it's not that having Concealment lets you describe creating a brooding pool of shadow; it's "because you generate a brooding pool of shadow, you can use the game-mechanic called Concealment" (44). That distinction is enforced again and again in the rules, especially in the way that it means that a single power can be built in a number of different ways depending on how you want your fiction to be enforced by the mechanics. Your armor might give you a blast power, but it's up to you how you build your powers to how that armor is treated by the mechanics. Can it be broken and stripped from you? Can it run out of juice and die on you? Is it essentially inviolable? At first, I was overwhelmed by the math and possibilities, but before I had finished my first read-through, I began to see all that the system allowed for and got excited about its application. And I say that as a person who doesn't care for much math in my RPGs, so that's saying something. The “Now” of the title refers to a “rule” in the game. I put “rule” in quotes because there are no mechanics that force “GMs” to use the technique, but to call it a bit of advice or a mere technique is to underscore the importance Edwards puts on it. The essence of the “Now” is to create a living, breathing world of consequential actions. At no point does the GM plan for an event or engineer a “plot.” Instead, the GM is to look at the world of PCs and NPCs (including institutions and large-scale forces) that the players themselves introduce when they create their characters and to ask him-/her-/themselves what those entities are up to and how are they responding to what has come before. For the PCs actions to have meaning, they must have ramifications, and the evidence of those ramifications comes in the way the world responds to them and pushes back. GMs are urged not to try to force the game to follow generic conventions (even at the level of, say, trying to put in a big battle in the second half of a session), but to let the “story” take care of itself as a matter of hindsight. Keep in the Now and everything else will take care of itself. I would love to see mechanics that make this kind of play happen, but they are not in this book. Instead, the game is constructed to make that style of play natural and easy. Characters come with a stack of choices that essentially build the world and the Now, giving the GM a ton of things to hold on to. Similarly, the villains the GM creates, through the process of building them just as the PCs are built, also contribute material to the Now, including how they will respond to the PCs. As Edwards notes in the text, the character sheets, both for the heroes and the villains, are everything that is needed to perpetuate play. The main tool on those character sheets are the “Situations.” The original Champions called them “Weaknesses,” but Edwards wisely changed their title to reflect their actual purpose. The player decides what aspects of the heroes lives are to be the subject of the story by selecting 100 points worth of Situations for their character. Do you want your hero’s secret identity to be a driving part of the narrative, pick that situation and get 15 points for it. Without picking that situation, you can still declare your character has a secret identity; it just doesn’t factor into the narrative in any interesting or meaningful way. This lets you build not only the character you want but give permission upfront for the what about their character might be the meat of any part of the narrative. Villains likewise have situations that let the GM know how they will interact with the narrative and the heroes beyond simply having goals that are occasionally opposed. It’s elegant and easy, and the list of possible situations creates reliable dramatic channels that create, without trying, the kinds of stories the game will naturally tell. The main thing discovered in and through play is what is your character about, what are they willing to push themselves for, to fight for, to risk their lives and their loved ones’ lives for. Learning this not only comes through the general decisions the players make on behalf of their character, but in all the tools the game gives them to show that determination. Chief among those tools is Endurance. Most things characters do, especially in battle, cost endurance, so characters need to choose wisely how to marshal that critical resource. Better yet, activities that use Endurance can be “pushed,” meaning that you can sink extra Endurance into an action to hit harder, run faster, strike more accurately all to get what’s important to you. This mirrors those best moments in superhero comics and it immediately makes the players’ decisions meaning and consequential. At the highest level, Edwards does a great job organizing his chapters, introducing concepts in a compelling order that builds logically and powerfully as it orients the reader to what is important within the game. However, in spite of that, there is bad news. There is no index, and information is scattered throughout the book, tucked in here and there so that you'll have a lot of moments where you remember reading a thing but have no idea where to find it again. If you have an electronic file and least you can do a word search. If you're reading on paper, you'll have a job to do. On my second read through the book, I created an index of my own with information I figured I would need or want later. In addition to having no index, it feels like the book was never given to a reader who had no familiarity with the game for the purposes of feedback. There were a lot of confusing moments that I thought would be clarified down the road but never were. I had to do a lot of detective work, bouncing back and forth between the rules and the example character builds. In the end, 99.9% of the information is all there, but you can't just casually pick it all up; you have to work for it! Or at least I did. Because I was interested in the material and the book, I found the work enjoyable if minorly frustrating. I expect a more casually-interested reader will not want to deal with the struggle. The other thing that I imagine is a difficulty is communicating all the rules well enough to my friends for them to play the game. Obviously, the rules of play can be explained during play, but there is a LOT of information players need to know and understand in order to even build a character. Hell, even if you were to give preconstructed characters, you would need to explain a ton of the game in order for them to use those characters well in play. The downside to having incredible freedom in building powers and characters, and the downside to having battles be determined by strategic play, is that players need to understand all the subtleties that allow for those strategies and that power. If this kind of thing revs your motor, you are going to purr all night long with the joys of the system, basking in the satisfied feelings that comes with system mastery and the endless possibilities the rules present. But if you can't find the friends to share that excitement, you're going to be like 10-year-old me making a few characters by yourself and dreaming of possibilities. Online play and groups that help you connect with other players are not uncommon now, so perhaps this won't be a problem for many. Also, Ron has an Adept Play Discourse channel where people can find other people with whom to play the game. I don’t much play superhero games, and I don’t much care for either mathematics or strategy in my RPG play, but I am genuinely excited to run this game for my friends. Beyond that, I really enjoyed the act of reading and thinking about this game and the way it works. I expect its success will be pretty niche, and that is a shame, given all it has to say.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed