|

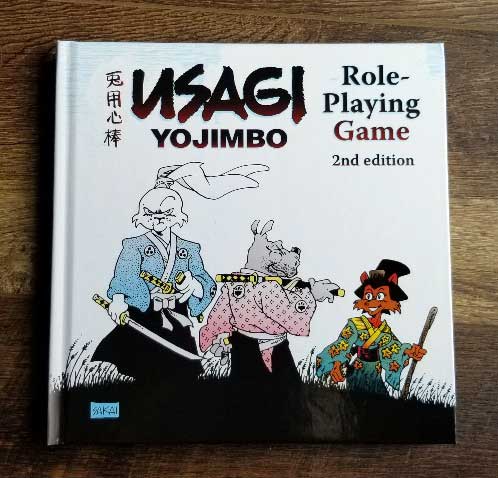

I’ve decided to read through the 3 Usagi Yojimbo RPGs, and I’m going to move backwards through time, starting with Sanguine’s second edition, which was funded via Kickstarter and released in 2019. I didn’t back the Kickstarter because I had heard unflattering reviews of Farflung, Sanguine’s other foray into Powered by the Apocalypse rules structure. Also, while I’ve been reading the comic books since 1986, I can’t think of any of my friends who would like to play the game, so putting money into a potentially bad game with no real prospect of playing it didn’t seem like a great idea.

But then Epidiah Ravachol created a little twitter thread regarding the game after he had gotten his copy. Epidiah is a huge fan of the first edition, so I was eager for his thoughts about this edition. He talked about a few of the game’s features (such as dividing the conversation into “casual,” “dicey,” and “combat” “moods”; the way story points become support points so that as you use the points to do awesome things you are then set up to help your friends do awesome things; and the way moves build upon each other in combat by giving you bonuses if your next move is also a combat move), and it was enough to spur me to action. Please note that I have not played the game as of this writing. Everything here are simply my thoughts on the rules as I have read them. My reading of the first 30 pages or so did not go well. I was put off by a number of things that weren’t specifically about the game. First, there is no acknowledgement section of games and designers that inspired this edition. In spite of using a ton of Meguey and Vincent Baker’s language, there is not one mention or nod to them or Apocalypse World. I’m used to the indie game publishing scene, which is very big on acknowledging influences and inspiration. And sure, Apocalypse World is pretty big, but it’s still tiny compared to the big games in the hobby, and I still encounter roleplayers regularly who have not heard of it. To use the language of moves, +1 forward, playbooks, and even MC for the gamemaster without giving credit is underhanded. In addition, the game disconnects moves from the fiction in a way that sent me reeling (or at least making diatribes in my marginalia). For example, players declare their characters will use their negotiate attribute and then roll the dice to see what they can do. The results are essentially either getting characters to do what you want or getting a character to believe some deception, which are two very different things. The move is not triggered by trying to deceive someone or trying to convince someone to do a thing, which adds an extra layer of work or knowledge, undermining the very thing that makes moves so effective in RPGs. Another example is the move Buddhism. On the result of a 7-9, you are given the following “menu” of options: “Perform strong doctoring on a sickly person. Or, invoke a strong aspect of Buddhism (banish spirits, etc.). Or, take five minutes and spend 1 support to remove 1 impairment from a friend. Or, give someone +1 back to a roll they just made. Or, spend 1 support to give someone +3 back.” Buddhism is essentially 4 moves in one. You can doctor an NPC, you can perform Buddhist rituals for narrative effect (banishing spirits is the only example given), you can spend some time with a fellow PC and remove an impairment, or you can act quickly enough to help a roll just made by them. On the one hand, I can see the argument that creating this one move instead of 4 is an act of concision. On the other hand, it demands that the players know the 4 things that the Buddhism move does and turns them into mere actions with effects rather than things that spring from fiction and then propel the fiction forward. I’ve seen some criticism that the designers don’t understand the pbta engine, as its popularly called, but I don’t think that’s it. This is a purposeful reimagining of how it works, but it removes everything that makes the engine worth using. The fictional triggers are removed and the gears that tie the move back into the fiction after the dice are thrown are equally removed. There are no GM moves, which means the GM does nothing in response to the dice except to interpret them and to offer an occasional hard bargain, make a ruling due to the situation, or declare a compromise. While I’m bitching, let me also say that the game presents the history, culture, and map of Japan in one of the least useful ways I’ve seen in an RPG. It’s block after block of text (yeah, with pictures and a few bullet points), but it’s all pretty mind-numbing and it needs to be plunged for inspiration rather than offering it up. Each section comes back to back following character creation and preceding the MC section. In addition, the game gives you a 26-page summary of various characters from the comic books, but they are presented in alphabetical order with tidbits of advice thrown in for incorporating the characters into your game. In the end it neither makes for a pool of inspiration or an easy-to-access resource to grab something you’re looking for. In other words, the information is fine, but the presentation is not the reader’s friend. Okay, so that’s all my complaining. Let’s get to the good stuff, because in spite of my extensive whining, there is some good stuff. The game has a cool approach to combat, on several different fronts. The game considers positioning in battle in a brief but meaningful way by saying that a character is either exposed, flanking, covered, or out of the combat. When you’re exposed, you are vulnerable to the enemy, but you can demand their attention, meaning that they can’t disengage with you at will. While you’re flanking, you are not the person all the enemies are attracted to, but nor can you demand their attention. Covered means that you are protected from enemies, but you can’t engage with them directly. Then, when you’re engaged in combat, each playbook has a fighting style and a weapon chart that tells you which weapons are within that style. In and of themselves, the styles don’t mean anything: the chart of what a 6-, 7-9, 10-12, and 13+ is the same for each style. But when you are using a weapon within your style, you get extra combat options when you roll a 10 or higher. For example, if you are using a bo staff, and it’s within your style, and you roll a 10 or higher, you can declare that you will use its “retreat” feature, which allows you to make a strong hit and then fall back to a covered position. Or if you are using a Daikyu bow, you can use the “aim” feature, which means that you don’t do any damage this turn, but next turn you get a +6 to your attack with that bow. These little features can make for all kinds of dynamic combat as you sweep, grapple, riposte, bind, retreat, and overextend yourself. The only weird feature in this approach is that you can’t declare one of these features as your intent since you can only use them on a strong hit. So you don’t say, “I’ll hit the thief with my bo staff and retreat to the cover of the building”; you say, “I’ll use my bo staff” then roll and see what you get, fashioning the fiction in response to your results. It’s not a bad way to play, but I imagine it can cause players to stumble who like to declare their intention before the dice are rolled. Same with that +6 with your bow. Your intention may have been to shoot a enemy, but the strong hit might make you change your mind, not fire, and take aim instead. There are actually a lot of bonuses to your future attacks, like that +6, during combat. The reason for that is that enemies are rated by the MC as weak, strong, or grand, and if you want any chance of landing a blow on a grand enemy, you’ll need a 13 or higher with your two 6-sided dice. When you roll to attack, you don’t add an attribute; instead, you roll +story points, which you accumulate as you play, so the farther you are in the story, the better violence will work for you. It’s a clever idea, even if I’m not a fan of the way story points are distributed (each adventure gives a story point to all characters after each act of the story, essentially—meh). I’m not usually a fan of giving enemies a rating as a GM, but I think the weak/strong/grand division is easy and natural, and I can see using it without a problem. There’s even a system for assigning points to an encounter so that the PCs chisel away at the points to overcome the enemies. Combat is a series of turns, with the PCs making their attacks, and then the PCs rolling a “response” to the enemies’ return attacks. It’s a workable system, and a necessary replacement to MC moves. I also like the damage system, which is inspired by a lot of indie games, going back to Sorcerer. There is no hit point system. During combat (or possibly other situations), PCs get “setback” points, and each time a PC receives a setback point, they have to roll minus their current total of setback points. Depending on the final score, some number of their attributes might become “impaired.” When the attribute is impaired, it doesn’t necessarily hurt their ability to do things, but if the player ever rolls doubles using an impaired stat, a negative event happens, hurting the characters narratively. As your setback points rise, you are more and more likely to have impaired attributes. If you setback attribute is ever impaired and you roll doubles making your check against setback points, then your character suffers grievous injuries or is taken out in some way. It’s a system that has a built-in curve to it and a nice element of chance. There are 4 adventures outlined at the end of the book, and each one is fine and useful. I feel like the game could have benefited from using more indie techniques to make scenario-building a fun element in and of itself. In a lot of ways, the Trollbabe system of scenario-creation would be perfect for the game as the players point out on a map of Japan where they want to go next. As in Trollbabe, the PCs are a set of outsiders walking into a relationship-web and interfering with the goings on there as they see fit, usually in the name of righteousness and helping the weak. Of course, as an MC of this game, you can crib Ron Edwards’s and others’ techniques, but it would seem reasonable to build something directly into the game to empower young MCs, especially since the game seems to be directed toward them at times, if I’m reading the tone of the writing and advice correctly. So my initial thought on reading the game was I’ll never play this. But having sat with it, thought about it, and played it through in my head, I’d definitely play this game, especially as a light-hearted hero romp. I’d be interested to see how the moves join together and how players navigate the relationship between the moves and the fiction.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed