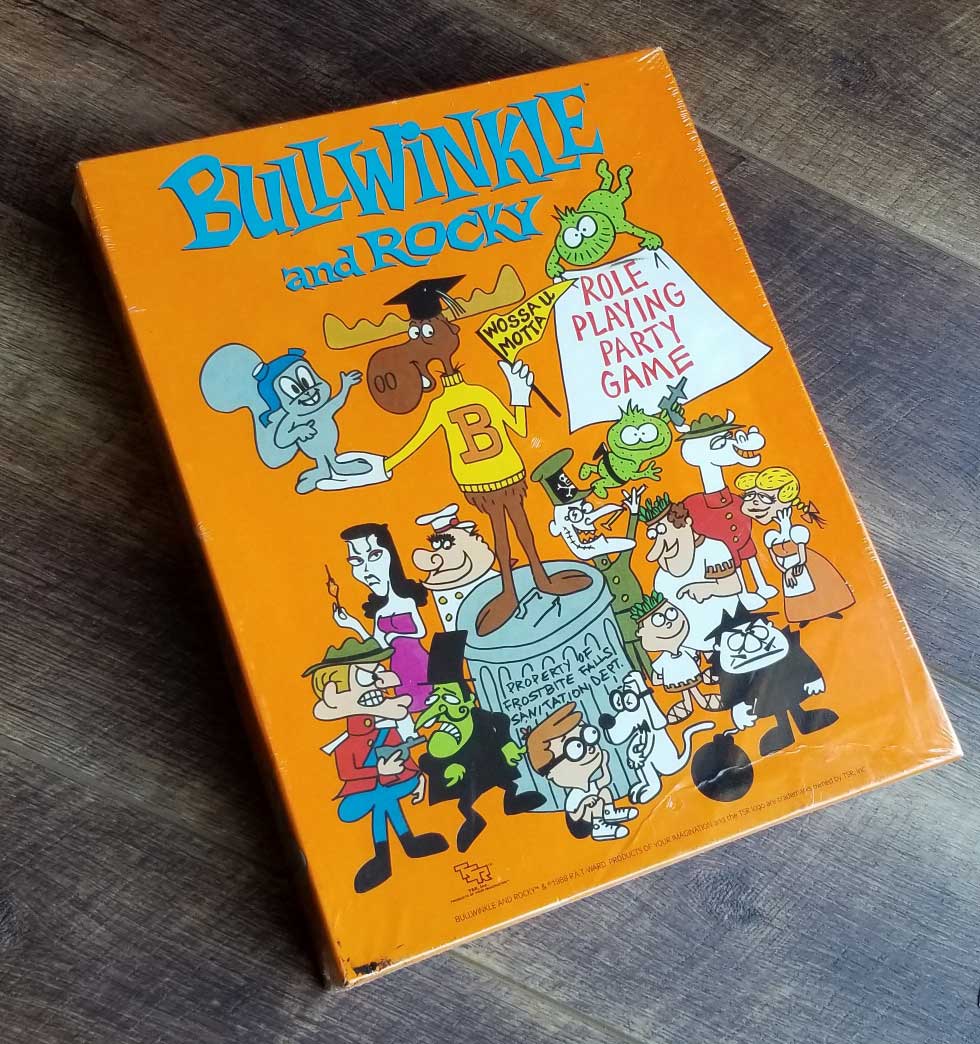

I bought The Bullwinkle and Rock Role-Playing Party Game off Ebay after Epidiah Ravachol posted a Twitter thread in which he explained (partially) why he is a big fan of the game. The mechanics and setup sounded really interesting, so I wanted to see for myself how it worked. I found a still-shrinkwrapped boxed set for less than $25 and ordered it. Not surprisingly, Epidiah was right: this is a really cool design for a roleplaying game. Many games have tackled the problem of introducing non-storytelling gamers to a storytelling game (I am of course using terminology from the 21st century, as the only words in the 80s for the kinds of games we played were RPGs), but this game has a great solution. First, they broke the game into 3 different games, to get players adjusted to what takes place in a roleplaying game. The first game uses the deck of 108 cards. The cards each have a person, place, thing, or event that happened in one of the Rocky and Bullwinkle episodes, such as “A ball of string”; “Pongo Britt, President of the Frostbite Falls Foistboinder Co.”; “Inherit something valuable!”; or “Explosive Mooseberries.” Most of the cards have an additional phrase, mirroring the punning and general wordplay of the series the game is based on. For example, “A close shave” has the subtitle “Or, just in the nick of time!” Players then select a storyline from the booklet entitled “Stories.” The players read the opening situation, the characters involved, and the ending of the story, and then deal out 5 cards to each player. (Smartly, the players then have a chance to throw out any cards they don’t want and draw back again to 5, a feature that similar card games would do well to emulate.) Then the players take turns progressing the story from the opening situation toward the ending, using the cards in their hands to inspire where they take the story. When they use an element from the card in their hand, they lay that card down and pass the storytelling to the next player. When everyone is down to their last card, game play pauses and the players think about how their card could get to the ending. The players who think they have a clever way to do it have a short competition to see who will finish the story and then wrap it up. This game takes all of two and a half pages to explain and served (I would guess) as the inspiration for games like “Once Upon a Time.” The game introduces a lot of key aspects of play. First, players can choose from any type of story from the show, meaning a Rocky and Bullwinkle story, a Fractured Fairytale, Aesop and Son, Peabody and Sherman, or Dudley Do-Right. Then players have a non-competitive, no-stress way to create a story together using the cards to lead them to say funny and surprising things. The goofier the story gets, the more fitting it is to the genre. Finally, the players learn to use the cards liberally as inspiration, not as exact things. So, that shaving card can be a literal shaving razor, a close call, someone getting cut by something sharp, or anything else the player wants to interpret it as. There are no rules for nixing someone else’s interpretation, so the card-player is the final arbiter of their contribution. The next game using foldable standees and introduces players to playing single characters in the creation of the story. Just as before, a story is picked from the book, but this time, they care about the opening situation, which characters are involved in the story, and what each one of those characters wants to achieve through the story, dividing those goals into things the good guys want and things the bad guys want. Players get a hand of cards, just as they did in the other game, too. This time, however, they choose one of the characters from the story and put the standee up in front of them. On one side of the standee is a picture of the character they are portraying, so everyone can see who you are. On the other side is a list of “powers” your character has and “Useful Sayings,” which are mostly catchphrases from the show, such as Rocky saying “Hokey Smokes!” or “Again? That trick never works!” The “powers” list tells you how your character acts in a story and what they can do. For example, Rocky can “fly,” is “nimble and quick,” and has “amazing trust.” The first says that any time the player wants, they can narrate Rocky flying. The next says that he can perform amazing feats of getting there in the last second. The third says that Rocky will believe people, even the villains if they are in disguise, have good intentions and can be trusted. You can see that the first gives them something fun to do, but the last two are about narrative conventions and fun ways to get the character into and out of trouble. I haven’t seen the show in eons, but the powers and sayings refreshed my memory even though it’s decades old and put me in the mindset of the show. A player looking at the cards in their hands and the back of their standee will have all kinds of ways to decide what to do when they are prompted. The other difference of the second game is that there is a Narrator. The Narrator is a standee card like the character cards, and the players take turns being the Narrator. The Narrator standee has a picture of a microphone on the one side, and a list of things the Narrator can and should do on the other. First, they can draw a card and discard a card if they want to. This is a great mechanic for keeping your cards fresh while still making them have weight. Second, there is a list of questions for the Narrator to ask as they please, and these questions basically set up the content and crisis of the scene: “Where is your character and what is he/she going to do?” “To what or whom are you going to do that?” “When are you going to do that?” “How are you going to do that?” “Are you going to let him/her get away with that?” “How are you going to stop that character from doing that to your character?” I think the Narrator card is amazing because it is an entire GM course on one card, and the player doesn’t even know they are GMing. Their only job is to ask questions and call for spins when those conditions are met. Yes, a spin. The game does have a resolution mechanism that kicks in when characters do something with “a real chance of failure” or when they “do something to another character” or if “there’s a disagreement between players.” Each character has their own spinner, a little cardboard card with the classic plastic spinner in the center. On each character’s card is some percentage “yes” and some percentage “no,” so that every spin results in a pass or fail state. The Yes/No ratio on each card skews heavily toward the No, which means that characters will be messing up regularly. Why? Because messing up is hilarious fun when you are telling a goofy story, and it is especially relevant to telling the type of stories on the Rocky and Bullwinkle show. In my conversation on Twitter with Epidiah, it occurred to me that the game uses all these game features that we associate with board games in play: cards, character standees, and spinners (and there are even plastic hand-puppets for being really goofy). In a lot of ways, I think the game is trying to make players comfortable with standard game pieces so that it feels like what they are doing is playing a more normal game than they really are. What I see in this game that is so impressive is how it breaks down the activities of roleplaying into these simple component parts and lets players jump in with little prep or pre-discussion. The GM tools are amazing, and the breadth of inspiration given to the players means that they will always have something fun and interesting to say when it’s their turn to speak. Hooking this system up to the Rocky and Bullwinkle show is brilliant because the show models interesting failure and is so goofy in its nature that players will not likely feel self-conscious during play or feel the pressure to make the “perfect” move. If you like storygames and like thinking about their design as creating interesting conversations, you can get a lot out of reading Bullwinkle and Rocky Role-Playing Party Game. It has influenced how I am thinking about things, and it even had a major influence on the game I designed to completion the other week. It’s a really rich game.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed