|

Edwards observes that games that strive for Simulationist play are easily drifted into Gamist play: "It also takes over easily mechanically in many instances of game design, especially in Simulationist-facilitating games, in two ways. The first way is to perceive system-based opportunities for advantage: breakpoints in point-allocation design, stacking of options into unique effects, and similar. Such things are often offered as neat add-ons in otherwise-Simulationist designs, but they take over fast when character niche-protection switches into literal character-defense. The second way, unsurprisingly, is through reward systems: a traditional character-improvement system can switch to a fully-social Step On Up reward system any time anyone wants, especially since it's self-perpetuating. . . .

The common reaction to this easy transition, for non-Gamist-inclined players, is pure terror - it's the Monsters from the Id! In-group conflicts over the issue have been repeated from group to group, game to game, throughout the entire history of the hobby. One such thing is a tug-of-war regarding following rules vs. not-following rules. What the rules actually say becomes yet another variable even as people argue about whether they should be followed, and when both of these issues are firing at once, nothing can possibly be resolved. The result is always to consider either following or ignoring rules to be 'right' when it goes your way. Another tack is for some groups and game designers to treat Gamism's easy 'in' as a necessary evil and to take an appeasement approach. The 'Id can be controlled, they say, as long as the Superego (the GM) stays firmly in charge and gives it occasional fights and a reward system based on improving effectiveness. This approach may rank among the most-commonly attempted yet least-successful tactic in all of game design. It will never actually work: the Lumpley Principle correctly places the rules and procedures of play at the mercy of the Social Contract, not the other way around. Therefore, even if such a game continues, it has this limping-along, gotta-put-up-with-Bob feel to it." GM as Superego to the Gamist Id is a pretty brilliant reading of that phenomenon.

0 Comments

One last thought on simulationism before I move on to Edwards’s essay on Gamism. By Edwards’s definition, “Simulationism heightens and focuses Exploration as the priority of play,” and those elements of Exploration are Character, Setting, Situation, System, and Color. I wonder if there’s not a weird sixth element that is Dramatic Narrative. I know that sounds odd, since all games create Dramatic Narratives in their way, but then all games have the other elements as well.

What got me thinking this is the way that every RPG strives to reproduce some aspect of our world, lives, or experiences in a recognizable way. That is part of the pleasure of the game, after all. And while Vincent Baker eschews simulation of reality in his game mechanics, what he loves to create through his mechanics (and thus have them reliably and reproducibly) are moments of Dramatic Narrative. The most exciting example of this is the resolution system in Dogs in the Vineyard. The raises and stakes of any conflict will always reproduce the beat by beat exchanges that we see in excellent television and movies and read in excellent books. It’s the best mechanical representation of this dramatic structure that I have seen. Similarly, all of the moves in Apocalypse World, for both the PCs and MC, are built to recreate (again reliably and reproducibly) the Dramatic Narratives of great fiction. The MC’s moves are a collection of dramatic elements, challenging experiences that can (and should) befall the protagonists in this fiction (separate them; capture someone; take away their stuff; offer an opportunity, with or without a cost; etc.). The variation available to the MC to create softer or harder moves allows the drama to escalate rhythmically as it does in fiction’s other forms, with the mechanics making it so that softer moves occur much more frequently than harder moves, ensuring that those climactic moments are rarer. The division of the PCs’ moves means that sometimes the characters will get what they want, sometimes we will be surprised by how bad things go, and usually things will kind of go the characters’ way but further entangle them in the fiction. Through play, we as both players and audience, get to experience the narrative as though it were a dramatic show unfolding right in front of us. It’s an incredible piece of design Nothing else in Apocalypse World is designed to simulate “reality.” Everything in it is designed to emulate the stylized “reality” of fiction, written and visual. It is “simulationist” to the extent that it (and Dogs in the Vineyard) prioritizes our play in the Exploration of the Dramatic Narratives they create. Is that just a crazy notion +Vincent Baker & +Meguey Baker? --- To which Vincent Baker responded: You're absolutely right that Dogs in the Vineyard and Apocalypse World are designed to create dramatic narratives. My Big Model answer is, they work this way by working on the elements of exploration. Dramatic narrative isn't a sixth element of exploration, it's a higher-level phenomenon; it emerges from the patterned interactions of system, color, situation, etc. Same with modeling reality, same with any other structure you might choose to design into your game. To put it into Apocalypse World's back cover terms: System, color, character, setting, situation - these are what you've got, yes. What are you going to do with them? GNS goes on to propose that there are three coherent answers. Whether that's true or not, answering the question coherently is, I think, synonymous with rpg design. In “Simulationism: The Right to Dream,” Ron Edwards asserts that the heart of Simulationist play is internal causality: “Consider Character, Setting, and Situation—and now consider what happens to them, over time. In Simulationist play, cause is the key, the imagined cosmos in action. The way these elements tie together, as well as how they’re Colored, are intended to produce ‘genre’ in the general sense of the term, especially since the meaning or point is supposed to emerge without extra attention. It’s a tall order: the relationship is supposed to turn out a certain way or set of ways, since what goes on ‘ought’ to go on, based in internal logic instead of intrusive agenda” [emphasis his]. The “intrusive agenda” refers to the other goal of Simulationist play: the lack of “metagame intrusions” during play.

Because an RPG seeking to provide Simulationist play wants to cut down on “metagame intrusions,” according to Edwards, the games often have an “engine” that runs things. I found his discussion of engines in RPGs very interesting, especially since the only engine I hear referred to today is the Apocalypse World engine, and no one is accusing Apocalypse World of being Simulationist. (No one, that is, except me in a post late last night. I know well that Apocalypse World is the very embodiment of Narrativist design put into practice, but several things about the way the game creates reliable and reproducible narrative drama gave me the idea that to some extent Apocalypse World simulates the drama—and damn well!—that we see on TV, in movies, and in books.) Here’s what Edwards says: “Simulationist play can address very different things, ranging from a focus on characters' most deep-psychology processes, to a focus on the kinetic impact and physiological effects of weapons, to a focus on economic trends and politics, and more. . . . “[T]he mechanics-emphasis of the modelling system are also highly variable: it can [be] handled strictly verbally (Drama), through the agency of charts and arrows, or through the agency of dice/Fortune mechanics. Any combination of these or anything like them are fine; what matters is that within the system, causality is clear, handled without metagame intrusion and without confusion on anyone's part. That's why it's often referred to as ‘the engine,’ and unlike other modes of play, the engine, upon being activated and further employed by players and GM, is expected to be the authoritative motive force for the game to ‘go.’ “The game engine, whatever it might be, is not to be messed with. It is causality among the five elements of play. Whether everyone has to get the engine in terms of its functions varies among games and among groups, but recognizing its authority as the causal agent is a big part of play. (To repeat, the engine's extent and detail aren't the point; I could be talking about a notecard of brief ‘stay in character’ requirements or a 300-page set of probability charts.)” There’s a lot here that puts me in mind of the Apocalypse World engine (by which I specifically mean “moves” and the narrative directions they create from the die roll). For example, “the engine, upon being activated and further employed by players and GM, is expected to the authoritative motive force for the game to ‘go.’” That is entirely true for Apocalypse World—the engine dictates movement and direction in ways that are out of the MC’s hands. Of course the MC can decide how hard or soft a move to make on a miss, and there are certainly metagame concerns at work throughout the game, but the results of a move are the law. You don’t reroll it or fudge the numbers; both the MC and the PCs have to live with the results. The move of Apocalypse World, as Edwards says, “is causality,” only the aspect of play being affected is not the “reality” of the world but the dramatic narrative of the world, and “recognizing its authority as the causal agent is a big part of play.” This is what led me to posit that Apocalypse world might be Simulationist to the extent that its engine consistently creates dramatic narrative that can feel like its own end. What it is simulating, in other words, is not “reality” but the dramatic structures of other art forms (books, movies, TV, etc.). In his response to my post, Vincent Baker cleared up what I was misunderstanding when I asked if narrative drama might not be a sixth element of Exploration. He said, and I’m rearranging his words here though maintaining their meaning: The modeling of reality in RPGs is a higher-level phenomenon that emerges from the patterned interactions of system, color, situation, etc. Go ahead and read that again, because it is powerful. As a quick follow up observation, here’s another passage from Edwards that comes right after the long passage I quoted above: “Many Simulationist systems also emphasize modularity - you've got the baseline engine for what happens, so for specialty phenomena, whatever new rules go on top must not violate or devalue that baseline. When a system is very strong in this regard, it's what most people call ‘universal’ or ‘generic,’ by which they mean customizable through addition.” The Apocalypse World engine is neither universal or generic, but it is incredibly modular, and we are seeing from all the hacks of the system that we have “the baseline engine for what happens” and that it is endlessly “customizable through addition.” In “Simulationism: The Right to Dream,” Ron Edwards talks about how in Simulationist games (as he defined them) character-creation itself is often part of play, and occasionally setting-creation is as well.

Again, this got me thinking of Apocalypse World. I have heard and read many times how RPers love the low/no-prep of starting an Apocalypse World game; you just get your friends together and watch it all come together. That aspect of the game is often pitched as an end in itself. What that actually means is that what was once work for the GM has been turned into play for all, like wine from water. When we say that an RPG is no-prep, what that means (ideally, I think) is that character, setting, and situation itself are all part of play. That’s a bitchin’ bit of design work. Sometimes when MCing an game using the Apocalypse World engine I find myself reaching for some sort of difficulty scale like a limb I had removed long ago but from which I still feel an itch.

Difficulty scales and target numbers for tasks is a hangover from traditional games, and are simulationist in nature, acting as a mechanic to replicate the notion that some things are easier to do than others. Vincent and Meguey of course junked that in their efforts to create an entirely narrativist game. And once I started looking at all the things I love in Apocalypse World, I see all the conscious rejections of anything that can be tied to the simulationist traditions. A rolled initiative? Screw that. Keeping tracks of money? Abstract the fuck out of that. Experience points? Check these boxes when you use the things that make your character awesome. Advancement? Here are more awesome things that you can do, so choose where you want the narrative to go and pick it. Hit points? Ha! What’s that weapon’s range? Far. Deal with it. Every aspect of traditional games has been given an abstraction or turned into a narrative moment. Any time the dice are rolled, it’s the narrative that’s going to be affected. God damn! That’s why it has changed RPGs like it has. "Points of Contact: The steps of rules-consultation, either in the text or internally, per unit of established imaginary content. This is not the same as the long-standing debate between Rules-light and Rules-heavy systems; either low or high Points of Contact systems can rely on strict rules."

-Ron Edwards, form "Simulationism: The Right to Dream" I’ve moved on to Ron Edwards’s essay “Simulationism: The Right to Dream,” and whether you agree with the GNS categories or not, there is a lot to chew on in this essay.

Here’s one passage that got me thinking: “Historically, the [Simulationist] System has been based on task resolution, not conflict resolution, regardless of scale. Don’t mistake ‘conflict’ for ‘large-scale task.’ “ In the more traditional games, task resolution is a big thing. In fact, in games with Skill lists and in which doing a task, whether it affects the narrative or not, comes with a roll, combat itself is really nothing more than a set of tasks (roll to hit, roll to parry, roll to dodge, etc.). One of the brilliant parts of the moves system as presented and used in the Bakers’s Apocalypse World is that it turns that whole paradigm on its head. In the traditional games, all conflicts are reduced to tasks whereas in Apocalypse World, all tasks are turned into conflicts. No matter what your character does, it is either accomplished without question (the command first voiced (to my understanding at least) in Dogs in the Vineyard to “roll dice or say yes”) or it is a move with the likelihood that new trouble will arise from the situation. "Rules bloat can also result from the design and writing process itself. Cogitating about in-game causes can transform itself, at the keyboard, into a sort of Exploration of its own, which results in very elaborate rules-sets for situational modifiers, encumbrance, movement, technology, prices of things, none of which is related to actual play of the game with actual people. During the writing process, 'what if' meets 'but also' and breeds tons of situational rules modifiers. . . . Don't spin your wheels defending your design against some other form of play."

-Ron Edwards, from "Simulationism: The Right to Dream" “The key for these games is GM authority over the story’s content and integrity at all points, including managing the input by players. Even system results are judged appropriate or not by the GM; ‘fudging’ Fortune outcomes is overtly granted as a GM right.

“The Golden Rule of White Wolf games is a covert way to say the same thing: ignore any rule that interferes with fun. No one, I presume, thinks that any player may invoke the Golden Rule at any time; what it’s really saying is that the GM may ignore any rule (or any player who invokes it) that ruins his or her idea of what should happen.” -Ron Edwards, from “Simulationism: The Right to Dream” One of my favorite paragraphs in Apocalypse world is right at the beginning of the Master of Ceremonies section: “There are a million ways to GM games; Apocalypse World calls for one way in particular. This chapter is it. Follow these rules. The whole rest of the game is built upon this.” The character moves are the lauded darlings of the Bakers’s game, but the MC rules are every bit as critical to the Apocalypse World engine. As they say, the whole game is built upon it. The conversation, while it plays out smoothly and organically, is actually tightly structured. Moreover, it is the MC’s moves that create all the narrative movement in the story, and you can’t force that story on the players unless they make a move or look to you to make their lives interesting. In a surprisingly short text, the Bakers codify an entire system of creating a cooperative story—and not just any story, but one that is dramatic and riveting and cool. "System is mainly composed of character creation, resolution, and reward mechanics."

-Ron Edwards, form "Simulationism: The Right to Dream" "'Role Levels': (1) The player's social role in terms of his character - the mom, the jokester, the organizer, the placator, etc. (2) The character's thematic or operational role relative to the others - the leader, the brick, the betrayer, the ingenue, etc. (3) The character's in-game occupation or social role - the pilot, the mercenary, the alien wanderer, etc. (4) The character's specific Effectiveness values - armor rating, weapon attributes, specific skills and their values, available funds, etc."

-Ron Edwards, from "Simulationism: The Right to Dream" Ron Edwards spends some time tearing into the incoherent design of Vampires: The Masquerade in "GNS and Other Matters of Role-playing Theory." He ends his discussion with these two sentences, which made me laugh:

"One may ask, if this design is so horribly dysfunctional, why is it so popular? The answer requires an economic perspective on RPGs, in addition to the conceptual and functional one outlined in this essay, and is best left for discussion." Ron Edwards on designing reward systems:

"What is being rewarded? Attendance? Role-playing per se? Player actions? Outcomes of conflicts? In-game moments? "Who is being rewarded, the player or the character? "Are reward systems necessary? At what scopes or time-frames of play are they more or less important? "If we are talking about character improvement, how does it proceed? Linearly or exponentially? If exponentially, is the exponent positive or negative?" -from "GNS and Other Matters of Role-playing Theory" Delving into the history and theory of RPGs and am currently enjoying Ron Edwards's pieces from The Forge. He is a rigorous thinker and a clear writer. I am currently on "GNS and Other Matters of Role-playing Theory," which has shifted the way I have been understanding Apocalypse World and other games.

The essay is a great introduction to the different aspects of RPG design and a great presentation of the language and concepts at issue in the games we play. "I do not recommend using 'genre' to identify role-playing content."

-Ron Edwards, "GNS and Other Matters of Role-playing Theory" That one was surprising, but it makes sense in the theoretical structure presented in the essay. Moreover, it got me thinking about genres and how a game can embrace a genre but simultaneously needs to be flexible enough to rise out of it. Apocalypse world does this by leaving all the details of the world, the apocalypse itself, and the psychic maelstrom undefined. But Vincent and Meguey Baker balance that openness by using their mechanics to nail down the specific type of story that Apocalypse World games will tell, namely stories about interdependent members of a community surviving in a land of want. The game is simultaneously incredibly focused and unbelievably broad, which makes for wonderful play. "In most Narrativist designs, Premise is based on one of the following models.

--A pre-play developed setting, in which case the characters develop into protagonists in the setting's conflicts over time. --Pre-play developed characters (protagonists), in which case the setting develops into a suitable framework for them over time." -Ron Edwards, "GNS and Other Matters of Role-playing Theory" To create a satisfying story, you either create characters who fit into a pre-made setting in such a way that they can become protagonists in those conflicts, or you have strongly defined characters suitable to be protagonists and let the story build up around them. Again, beautiful in its simplicity. Obviously AW and pbta games go for the second option: here are pre-made, already-awesome characters (to a degree), and now let's play the world to figure out what their story actually is. Ron Edwards provides a list of ways that GMs can prepare for a session, and it's a good breakdown of the common ways different RPGs demand to be played. Your game is probably making one of these demands (or an entirely different demand) even if it doesn't explicitly say so in the text:

"Linear adventures, in which the GM has provided a series of prepared, in-order encounters. "Linear, branched adventures, in which the GM has done the same as above but provides for the players proceeding in more than one direction or sequence. "Roads to Rome, in which the GM has prepared a climactic scene and maneuvers or otherwise determines that character activity leads to this scene. (In practice, 'winging it' usually becomes this method.) "Bang-driven, in which the GM has prepared a series of instigating events but has not anticipated a specific outcome or confrontation. (This is precisely the opposite of Roads to Rome.) "Relationship map, in which the GM has prepared a complex back-story whose members, when encountered by the characters, respond according to the characters' actions, but no sequence or outcomes of these encounters have been predetermined. "Intuitive continuity, in which the GM uses the players' interests and actions during initial play to construct the crises and actual content of later play." -from "GNS and Other Matters of Role-playing Theory," October 2001 "A great deal of intellectual suffering has occurred due to the linked claims that role-playing either is or is not 'story-oriented,' and that one falls on one side or the other of this dichotomy. I consider this terminology and its implications to be wholly false. . . . Story-stuff and/or character stuff is so important to all these approaches that the difference in processes and point of role-playing are easy to miss, or, disastrously, easy to deny." - Ron Edwards, "GNS and Other Matters of Role-playing Theory

"Unfortunately, I think that many RPG designers were and are flying entirely by the seat of their pants. Their attention was on in-game named elements like 'strength' and 'percent to hit' rather than Effectiveness. Such an approach to character design allows latitude for all sorts of emergent properties, such as point-mongering in Champions or the mini-maxing in most late 80s games, or any number of other 'take-over' elements of play that subvert the stated goal of the design." - Ron Edwards, "GNS and Other Matters of Role-playing Theory"

This makes me think of the simplicity and beauty of AW's stats (+2, +1, 0, -1) as pure measures of Effectiveness. You know precisely how those numbers will work and their relative strengths, even if it's your first time picking up the game. Ron Edwards on Incoherent Design

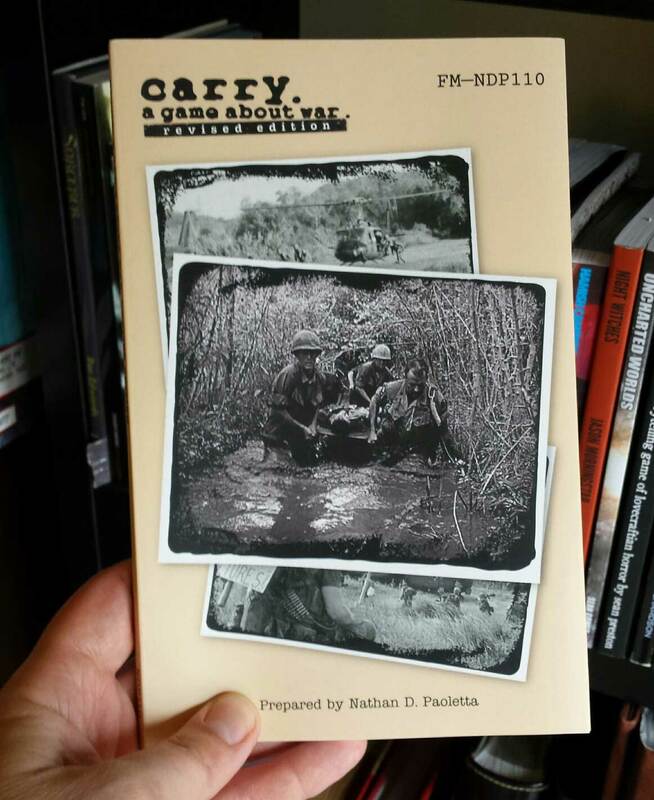

"All of these games are based on The Great Impossible Thing to Believe Before Breakfast: that the GM may be defined as the author of the ongoing story, and, simultaneously, the players may determine the actions of the characters as the story's protagonists. This is impossible. It's even absurd. However, game after game, introduction after introduction, and discussion after discussion, it is repeated." -from "GNS and Other Matters of Role-playing Theory" So, I told myself I wasn't going to buy any more RPGs until Gen Con (outside of backing some Kickstarters of course), but then +Nathan Paoletta made his revised edition of carry available. I'm not made of stone.

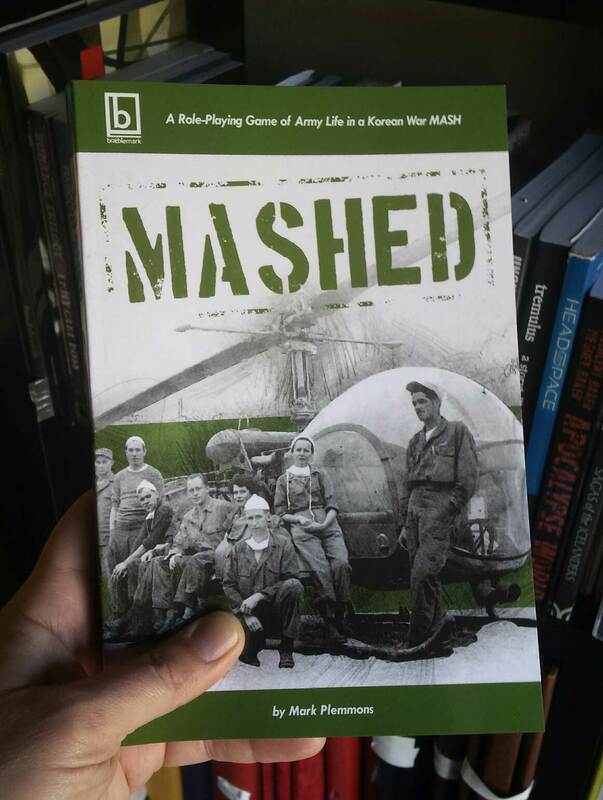

And checkout this brilliant element: You see that cover? It is removable--the inside of the top half has the various tables and rules charts printed there, and the inside of the bottom half has a map of Vietnam. Looking forward to reading it and bringing it to the table! Mark Plemmons's MASHED arrived with today's mail and looks awesome!

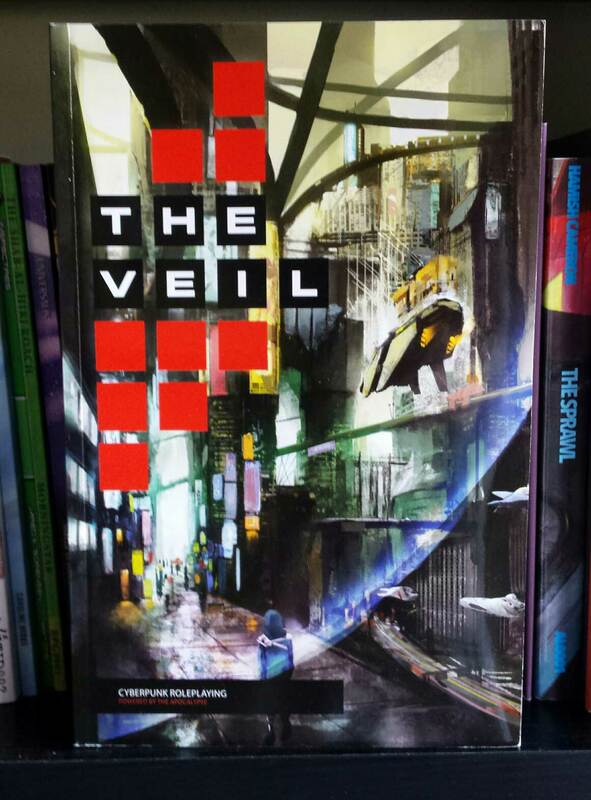

Kickstarter reward received! +Fraser Simons' The Veil came in today's post, and it is a gorgeous book with glossy page after page of incredible, inspirational, mood-setting, idea-sparking art! I'm excited to get to read and play it!

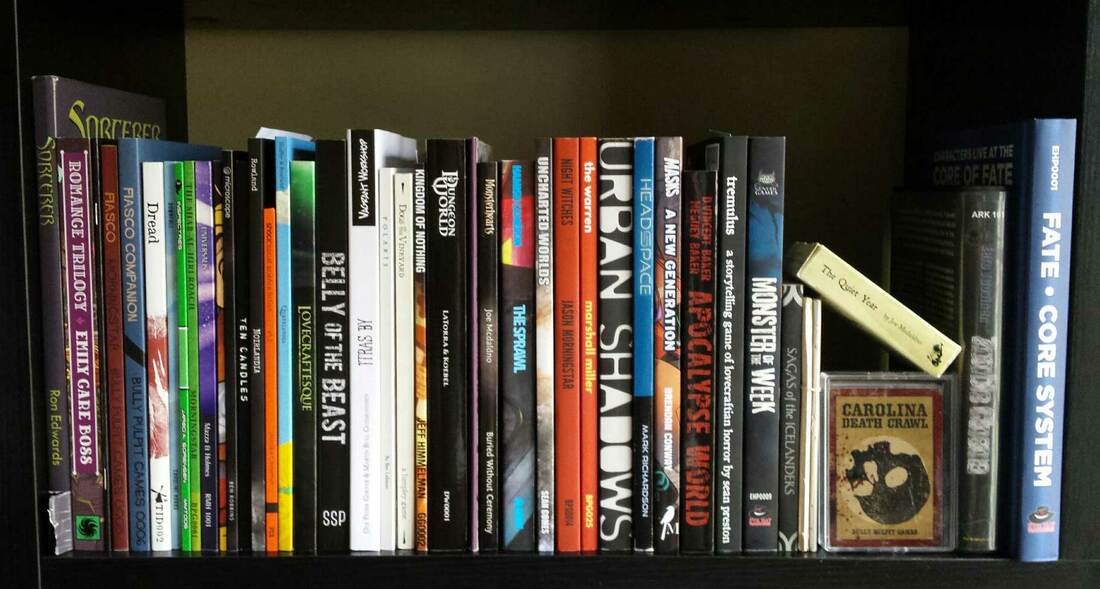

Here's a pic of my Indie RPG game shelf (#GameShelfie?)

I discovered there was more to RPGs than the traditional games of my youth in the fall of 2015 when a game of Fiasco blew the top of my head off. In the last year and a half, I have been trying like mad to catch up with what has been going on in the last dozen years or so. I was playing MTG regularly, but last year I didn't buy a single card and instead channeled that budget over to this new/old hobby, and I couldn't be happier to have done so. Just played my first game of +Evan Rowland's Noirlandia with my wife +Ann D and our friend Phil! We created a city corrupted by technology that we absolutely fell in love with, and then proceeded to roll and flip cards with the worst luck. All of our leads ended up in a single district, which meant that after the first scene, when two black 6s were thrown, we had two escalated districts. On the third scene, the third district was escalated and the game was over. Boom. We unearthed 3 leads and made one connection before our intrepid investigators' journey came to an end.

Even with that rough luck, we were all really satisfied with the story we were able to tell by the end of our epilogues, which tells you how strong the game is. It's a smartly designed game, and after the first scene, we had the hang of how the challenge and investigation rolls went and could move the narrative along smoothly. We are all excited to play again in the near future and hopefully find an answer or two to the murder before the city explodes into corruption! |

Jason D'AngeloRPG enthusiast interested in theory and indie publications. Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed