|

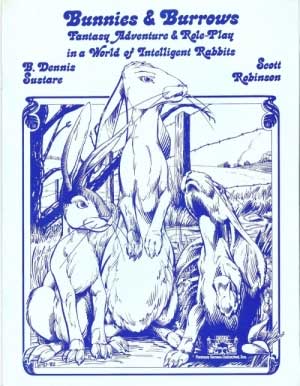

I’ve decided to read through the 3 Usagi Yojimbo RPGs, and I’m going to move backwards through time, starting with Sanguine’s second edition, which was funded via Kickstarter and released in 2019. I didn’t back the Kickstarter because I had heard unflattering reviews of Farflung, Sanguine’s other foray into Powered by the Apocalypse rules structure. Also, while I’ve been reading the comic books since 1986, I can’t think of any of my friends who would like to play the game, so putting money into a potentially bad game with no real prospect of playing it didn’t seem like a great idea.

But then Epidiah Ravachol created a little twitter thread regarding the game after he had gotten his copy. Epidiah is a huge fan of the first edition, so I was eager for his thoughts about this edition. He talked about a few of the game’s features (such as dividing the conversation into “casual,” “dicey,” and “combat” “moods”; the way story points become support points so that as you use the points to do awesome things you are then set up to help your friends do awesome things; and the way moves build upon each other in combat by giving you bonuses if your next move is also a combat move), and it was enough to spur me to action. Please note that I have not played the game as of this writing. Everything here are simply my thoughts on the rules as I have read them. My reading of the first 30 pages or so did not go well. I was put off by a number of things that weren’t specifically about the game. First, there is no acknowledgement section of games and designers that inspired this edition. In spite of using a ton of Meguey and Vincent Baker’s language, there is not one mention or nod to them or Apocalypse World. I’m used to the indie game publishing scene, which is very big on acknowledging influences and inspiration. And sure, Apocalypse World is pretty big, but it’s still tiny compared to the big games in the hobby, and I still encounter roleplayers regularly who have not heard of it. To use the language of moves, +1 forward, playbooks, and even MC for the gamemaster without giving credit is underhanded. In addition, the game disconnects moves from the fiction in a way that sent me reeling (or at least making diatribes in my marginalia). For example, players declare their characters will use their negotiate attribute and then roll the dice to see what they can do. The results are essentially either getting characters to do what you want or getting a character to believe some deception, which are two very different things. The move is not triggered by trying to deceive someone or trying to convince someone to do a thing, which adds an extra layer of work or knowledge, undermining the very thing that makes moves so effective in RPGs. Another example is the move Buddhism. On the result of a 7-9, you are given the following “menu” of options: “Perform strong doctoring on a sickly person. Or, invoke a strong aspect of Buddhism (banish spirits, etc.). Or, take five minutes and spend 1 support to remove 1 impairment from a friend. Or, give someone +1 back to a roll they just made. Or, spend 1 support to give someone +3 back.” Buddhism is essentially 4 moves in one. You can doctor an NPC, you can perform Buddhist rituals for narrative effect (banishing spirits is the only example given), you can spend some time with a fellow PC and remove an impairment, or you can act quickly enough to help a roll just made by them. On the one hand, I can see the argument that creating this one move instead of 4 is an act of concision. On the other hand, it demands that the players know the 4 things that the Buddhism move does and turns them into mere actions with effects rather than things that spring from fiction and then propel the fiction forward. I’ve seen some criticism that the designers don’t understand the pbta engine, as its popularly called, but I don’t think that’s it. This is a purposeful reimagining of how it works, but it removes everything that makes the engine worth using. The fictional triggers are removed and the gears that tie the move back into the fiction after the dice are thrown are equally removed. There are no GM moves, which means the GM does nothing in response to the dice except to interpret them and to offer an occasional hard bargain, make a ruling due to the situation, or declare a compromise. While I’m bitching, let me also say that the game presents the history, culture, and map of Japan in one of the least useful ways I’ve seen in an RPG. It’s block after block of text (yeah, with pictures and a few bullet points), but it’s all pretty mind-numbing and it needs to be plunged for inspiration rather than offering it up. Each section comes back to back following character creation and preceding the MC section. In addition, the game gives you a 26-page summary of various characters from the comic books, but they are presented in alphabetical order with tidbits of advice thrown in for incorporating the characters into your game. In the end it neither makes for a pool of inspiration or an easy-to-access resource to grab something you’re looking for. In other words, the information is fine, but the presentation is not the reader’s friend. Okay, so that’s all my complaining. Let’s get to the good stuff, because in spite of my extensive whining, there is some good stuff. The game has a cool approach to combat, on several different fronts. The game considers positioning in battle in a brief but meaningful way by saying that a character is either exposed, flanking, covered, or out of the combat. When you’re exposed, you are vulnerable to the enemy, but you can demand their attention, meaning that they can’t disengage with you at will. While you’re flanking, you are not the person all the enemies are attracted to, but nor can you demand their attention. Covered means that you are protected from enemies, but you can’t engage with them directly. Then, when you’re engaged in combat, each playbook has a fighting style and a weapon chart that tells you which weapons are within that style. In and of themselves, the styles don’t mean anything: the chart of what a 6-, 7-9, 10-12, and 13+ is the same for each style. But when you are using a weapon within your style, you get extra combat options when you roll a 10 or higher. For example, if you are using a bo staff, and it’s within your style, and you roll a 10 or higher, you can declare that you will use its “retreat” feature, which allows you to make a strong hit and then fall back to a covered position. Or if you are using a Daikyu bow, you can use the “aim” feature, which means that you don’t do any damage this turn, but next turn you get a +6 to your attack with that bow. These little features can make for all kinds of dynamic combat as you sweep, grapple, riposte, bind, retreat, and overextend yourself. The only weird feature in this approach is that you can’t declare one of these features as your intent since you can only use them on a strong hit. So you don’t say, “I’ll hit the thief with my bo staff and retreat to the cover of the building”; you say, “I’ll use my bo staff” then roll and see what you get, fashioning the fiction in response to your results. It’s not a bad way to play, but I imagine it can cause players to stumble who like to declare their intention before the dice are rolled. Same with that +6 with your bow. Your intention may have been to shoot a enemy, but the strong hit might make you change your mind, not fire, and take aim instead. There are actually a lot of bonuses to your future attacks, like that +6, during combat. The reason for that is that enemies are rated by the MC as weak, strong, or grand, and if you want any chance of landing a blow on a grand enemy, you’ll need a 13 or higher with your two 6-sided dice. When you roll to attack, you don’t add an attribute; instead, you roll +story points, which you accumulate as you play, so the farther you are in the story, the better violence will work for you. It’s a clever idea, even if I’m not a fan of the way story points are distributed (each adventure gives a story point to all characters after each act of the story, essentially—meh). I’m not usually a fan of giving enemies a rating as a GM, but I think the weak/strong/grand division is easy and natural, and I can see using it without a problem. There’s even a system for assigning points to an encounter so that the PCs chisel away at the points to overcome the enemies. Combat is a series of turns, with the PCs making their attacks, and then the PCs rolling a “response” to the enemies’ return attacks. It’s a workable system, and a necessary replacement to MC moves. I also like the damage system, which is inspired by a lot of indie games, going back to Sorcerer. There is no hit point system. During combat (or possibly other situations), PCs get “setback” points, and each time a PC receives a setback point, they have to roll minus their current total of setback points. Depending on the final score, some number of their attributes might become “impaired.” When the attribute is impaired, it doesn’t necessarily hurt their ability to do things, but if the player ever rolls doubles using an impaired stat, a negative event happens, hurting the characters narratively. As your setback points rise, you are more and more likely to have impaired attributes. If you setback attribute is ever impaired and you roll doubles making your check against setback points, then your character suffers grievous injuries or is taken out in some way. It’s a system that has a built-in curve to it and a nice element of chance. There are 4 adventures outlined at the end of the book, and each one is fine and useful. I feel like the game could have benefited from using more indie techniques to make scenario-building a fun element in and of itself. In a lot of ways, the Trollbabe system of scenario-creation would be perfect for the game as the players point out on a map of Japan where they want to go next. As in Trollbabe, the PCs are a set of outsiders walking into a relationship-web and interfering with the goings on there as they see fit, usually in the name of righteousness and helping the weak. Of course, as an MC of this game, you can crib Ron Edwards’s and others’ techniques, but it would seem reasonable to build something directly into the game to empower young MCs, especially since the game seems to be directed toward them at times, if I’m reading the tone of the writing and advice correctly. So my initial thought on reading the game was I’ll never play this. But having sat with it, thought about it, and played it through in my head, I’d definitely play this game, especially as a light-hearted hero romp. I’d be interested to see how the moves join together and how players navigate the relationship between the moves and the fiction.

0 Comments

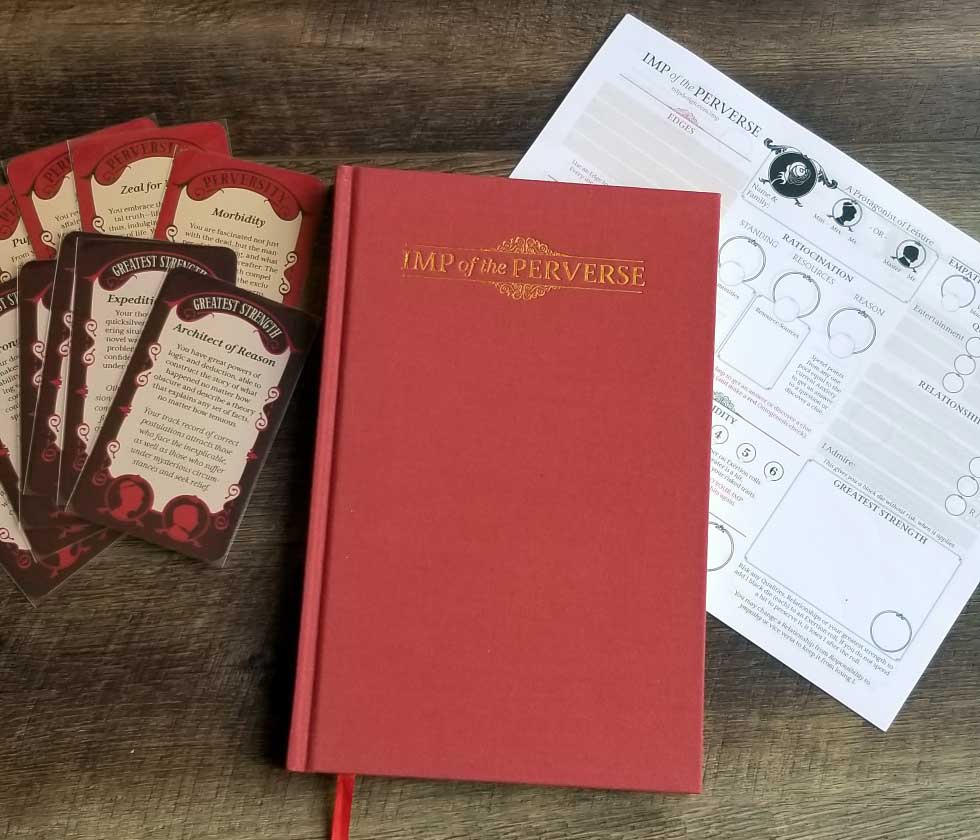

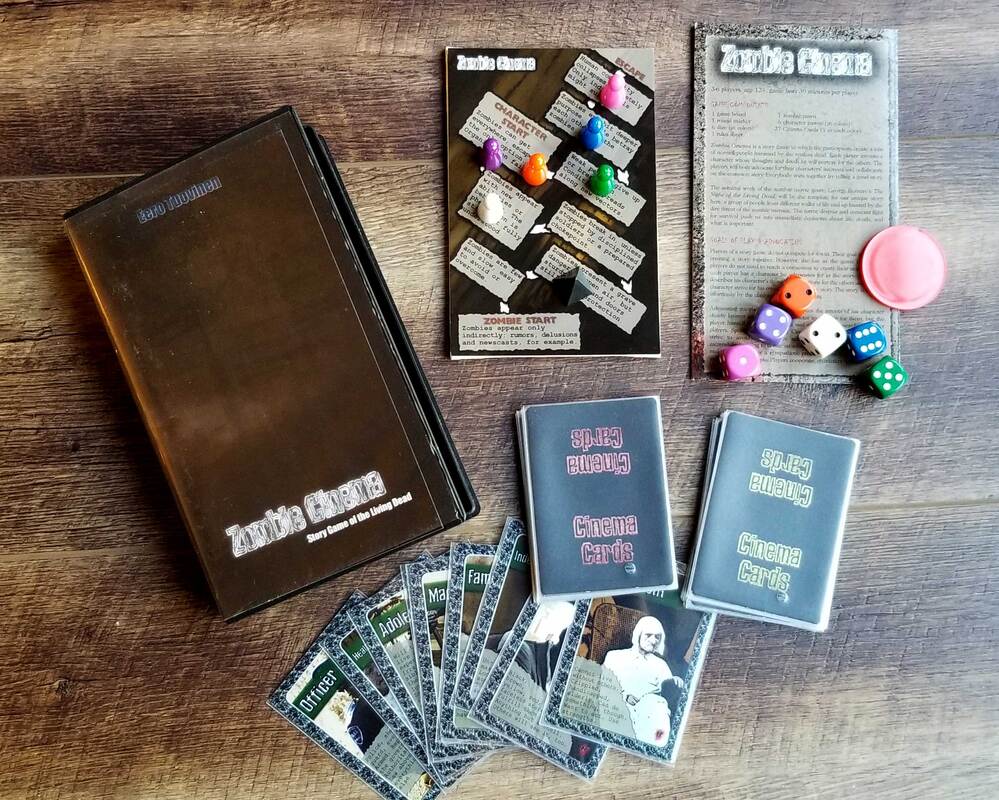

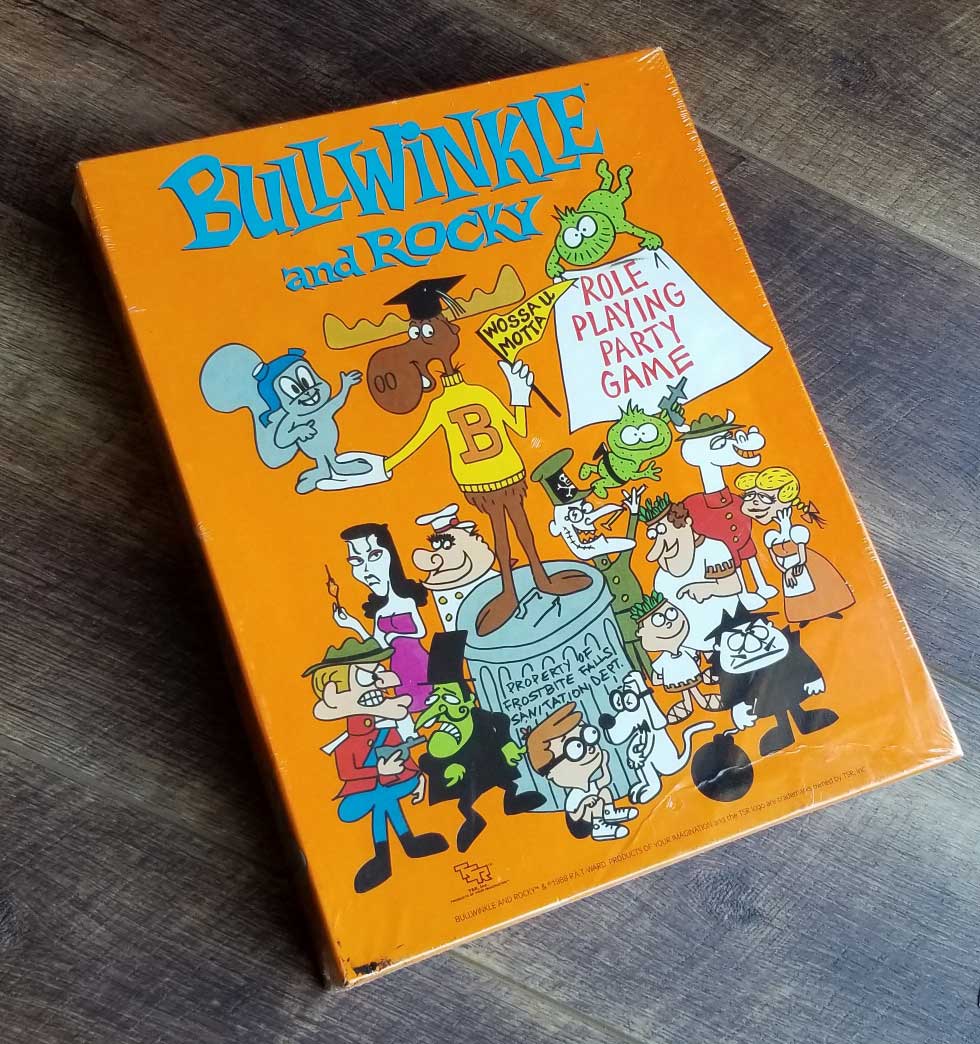

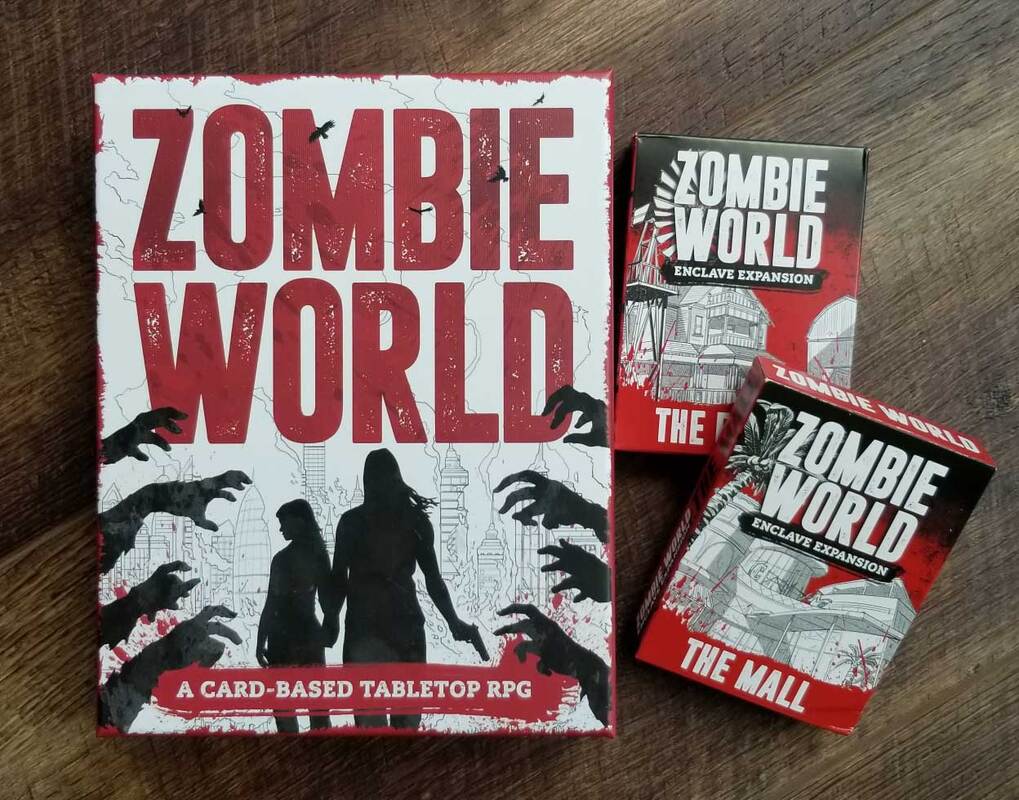

This is one of my read-only reviews, by which I mean I have not taken the game to the table or watched any APs. And more than a review, this post is a way for me to gather my thoughts about the text and the game. If it’s useful to you or if you want to jump in with your own thoughts about it and have a conversation, that’s awesome. In The Imp of the Perverse, players create monster hunters in America during the Jacksonian era, which is defined in the game as the 20-year stretch between 1830 and 1850. The premise is that the “Shroud” that separates the world of the living and the world of the dead is susceptible to strong human passions: “Human passions sometimes pierce this barrier, inviting the terrible things that we still remember as monsters” (13). The eponymous imps encourage the living to feed their strong perverse passions to breach the Shroud. The PCs are in a position to perceive, understand, and fight these Shroud-shredding imps and the human beings they corrupt because they have imps of their own. In any given session, the PCs investigate, pursue, and eventually defeat a monster of perversity. The question posed by the game is this: what will become of your PC in this pursuit? Will they rid themselves of their imp, thereby rejoining human society in full and leaving their monster-hunting days behind them, or will they indulge their perversity too often and become one of the monsters in need of hunting? It’s a great concept and a cool world. When I first heard the pitch, I thought of Ron Edwards’s Sorcerer and wondered if this wasn’t a kind of hack of that game. Human beings given special powers by demons while their humanity is on the line is a fine summary of both games. But while the games have a similar focus, they play dramatically differently. Inspiration may have come from Sorcerer (which I was surprised to see is not in the list of inspirational games in the appendices’ Ludography), but the games are very different. As you can probably tell from my above summary, this is a game about characters and the changes they undergo from their experiences in the hunt. When you first build your PC, you bedeck them with a set of stat pools, ranked traits and relationships, a greatest strength and driving perversity, and a meaningful past. In the course of play, you spend those pools, risk those traits and relationships, draw on your greatest strength, and lean on your perversity in order track, understand, and finally banish the monster. Those resources you draw on don’t automatically refill and reform between sessions. Instead, relationships can be broken or their nature can shift, and its up to the player (and the dice) to decide if they are repaired or lost. Resource pools can be drained. Your greatest strength can be worn away. Your perversity can grow. Your defining traits can wax, wane, disappear, or be replaced by new ones. The thrill of playing a character in this game is to watch how it changes in the face of the horrors it fights, and all the mechanics are designed to affect those changes. It’s really cool. I love the way Paoletta does character creation in Imp. He has what he calls a “survey” for creating characters, which is a list of options concerning different fictional features of your character. Each one of those choices affects your stat pools, traits (called Qualities), and relationships. Generally speaking, I think this is an excellent way to build a character: choosing fictional features which then create mechanical teeth. Specifically in this game, I think Paoletta has a fantastic execution of the practice. Players start by choosing a career for their character. In order to avoid having a monstrous list of careers, each with their own accompanying mechanical details, Paoletta creates 8 broad categories: careers of affairs, arms, exploration, leisure, letters, opportunity, service, and survival. Not only does this allow him to have manageable categories, it’s a neat way for a player to get into their character and begin to build a guiding concept. This is such a simple solution, but it’s one of the features of the game that got me really excited. When your character can be anything, it’s overwhelming. Reducing those to 6 choices on each survey lightens the creative load while simultaneously giving you things to think about. For example, let’s say your struck by the idea of having a character whose career is one of service, you know that their service gives them financial resources (Quality: Resourceful 2), an employer (Relationship with whom you serve 1), and a place within the community your work (Standing with your community +2). So to flesh out those choices mean that you choose your employer and your community, which helps you narrow down your work and the idea of who your character is naturally flowers from that. That’s great tech. After you’ve chosen how your character’s gender presents itself, what kind of family you come from and where, and if your married or have children, you have most of your mechanical features in place. You then decide on your characters “greatest strength,” what defines them as a protagonist, and what their core perversity is, what their defining flaw is that compromises and threatens their humanity. According to the rules, deciding on these features is part of a “workshop” during character creation. During the workshop, everyone shares what they are thinking and the group helps shape those choices so that they are productive for the game and clear to all the players. That clarity is key, because in play, each player will be able to play the role of your imp insofar as they can tempt you to embrace your perversity within a conflict in order to get more dice and increase your chances for success. Character creation is already supposed to be done as a group in its own session, but this workshop feature ensures a necessary conversation and corresponding understanding. Finally, you decide if your character is new to hunting monsters or already experienced. This choice gives you a supernatural power if you’ve hunted before, and no matter what you choose, it establishes your “empathy” and “lucidity” ratings. Empathy is a resource you can use to gather information about the monster, an advantage especially late in the game. Philosophically, it represents the fact that you, as a fellow sufferer of an imp’s perversity, have insight into what the monster is going through and into the why and the how of their actions. Lucidity measures your humanity. Lucidity is a number between 1 and 6. If lucidity ever hits one, you have lost your humanity and have become a monster of your perversity. If lucidity ever hits 6, you have shaken your perversity, ensured your humanity, and retire from monster hunting. Once you’ve created your character, everything in play, as I’ve said, is designed to change your character sheet. But before I can talk about that, let’s talk about the main mechanics in the game: exertion and ratiocination. You make an exertion roll primarily “when you impose your will upon the world.” I love this trigger. Note that “[y]ou do not need to roll when an outcome is simply uncertain” (67) or risky, which is the measure so many other games use to decide when a resolution mechanic kicks in. To define exertion as imposing your will upon the world, it does a lot of work to clarify the fiction and the nature of the conflict. To impose your will upon the world is to say that you have a desired outcome and a desired course of action to attain that outcome, so the nature of the conflict and part of the stakes is defined to even call for the exertion roll. Moreover, this definition allows all kinds of actions to trigger the exertion roll, not just violence. To argue with someone to change their mind is to exert your will. To persuade someone to let you in is to exert your will. To threaten someone to stand down and keep what they’ve seen to themselves is to exert your will. And in this context, risking your various Qualities, relationships, and greatest strength create details in the fiction beyond their mechanical function. So if I’m arguing with someone to give up a secret and I bring in my relationship with my son, then I would have to have a reason that that relationship is relevant. Or if I bring in my Unhappy quality, I need to make it relevant to the argument. In this way, Qualities and relationships move from things on my character sheet to active fiction, and a resource for me to lean on to flesh out a scene, not just things to check off to accomplish something. To bring those things from my character sheet into my conflict also means that I am risking them. To risk a relationship means that I might lose that relationship or that the nature of the relationship might change. So not only are you warned not to risk something if you’re not willing to lose it, but once again those things become clear stakes in the conflict. It’s fantastic design because these elements on your character sheet are first, fictional details, second mechanical teeth in the gears of the game, and third resources for things to say during play. Staring down at your character sheet in the middle of the game will almost always give you something useful to say. When you exert yourself, you create a pool of black and red six-sided dice by what you risk, if you’re helped, and what influence you allow your imp to have. You roll that pool, and every dice that is as high as your lucidity score or higher is a success. If you are unhappy with your number of successes and can create at least one additional success by lowering your lucidity score, you can do so, driving your character into the arms of their imp in the name of success. The closer you are to human, the harder it is to exert yourself, so the game encourages you to embrace your imp in a substantial but subtle way. Once you have your pool of successes, you can spend them. You must spend one success to achieve the thing you set out to do, if you want to. You can spend successes to protect the qualities and relationships your risked to improve your dice pool. If you choose not to spend a success doing so, that quality or relationship is reduced by one rank. If it is reduced to zero, it is gone, and you can interpret what that means. Well, actually, relationships are protected to a degree, so you don’t have loved one dying on you or leaving you every time you roll. Instead of reducing the rank of the relationship, you have the choice to switch the nature of the relationship, which has cool fictional effects, but I won’t go into that here. What Paoletta achieves by this system is something you can see him striving for in Annalise. In Annalise, players create orthogonal stakes for a conflict, so that the player must chose which stakes to win and which to lose. The system in Annalise was derived from Vincent Baker’s Otherkind dice, which Baker developed into Apocalypse World moves. Paoletta developed them instead into what we see here in Imp of the Perverse, and it is a elegant and impressive development. Now to get us back to the idea that the character sheet is always changing. In play, your resource pools deplete; your qualities, relationships, and greatest strength drop in ranking; and your lucidity slides down toward inhumanity. All the while, you are putting checkmarks, red and black, in your “Ontogenesis” circles at the bottom of your character sheet. Once you have defeated the monster and concluded that game’s session, you can spend those checkmarks to refill your pools, bolster your relationship (or start new ones), build up your qualities (or create new ones), and reinvest in your greatest strength. At this point, you don’t just try to rebuild the character you began with. You are forced to ask yourself, “how has this experience changed my character?” And with that, you spend your points and see who your character is now. The odds of you ending where you began is close to nil, so not only does your sheet change during play, it changes significantly between monster-hunting sessions. Paoletta says at the beginning of his text that this game isn’t about whether or not you can catch and defeat the monsters; you can and will. The question instead is what will become of your character. And to that end, every mechanic in the game comes back to the character sheet and how play affects it. Finally, after you spend your checks, you roll black dice equal to the number of black checks you had and red dice equal to the number of red checks you had and add up each pool of colored dice. If the black dice total is higher, your lucidity shifts up one. If the red dice total is higher, your lucidity shifts down one. What this means is that there is one step that is not entirely in your control in terms of your lucidity shift, though you can shape your odds during play by seeking black or red checks through the actions you take. Because you can only shift one space, you know that having a 3 or 4 lucidity will not push your PC out of the game, but flirting with a 2 or a 5 presents the risk that you will hit 1 or 6 during Ontogenesis. Of course, this also means that you can drive you character to monsterhood or usher them to full humanity by your choices during play. And the coolest part? If you lean into your imp and drive your lucidity into the ground, your PC will become the next monster of perversity the other PCs have to hunt. How’s that for an incredible character arc? And if you want to stay in control of your character, even as a monster, you are invited to GM that session. Imp of the Perverse is full of cool design choices. Beyond those design elements, the structure and layout of the book is excellently done. This book has one of the best introductory chapters I’ve read in terms of clarity of purpose and vision. Each chapter that follows has an express purpose, and while it is not a thin book, it is never unfocused or wandering. In addition, Paoletta writes with exacting clarity and fills the book with footnotes (in the style of 19th-century books) that are constantly directing you to relevant sections. That feature, along with a thoughtful index makes the book an excellent reference book as well as an instructional book. The other great challenge the book faced was giving players the historical and cultural information needed to play the game and be inspired to run the game. The chapters on Jacksonian Gothic America are top shelf in terms of giving you enough information and enough inspiration to want to charge ahead without weighing you down with burdensome facts. It’s a delicate wire to balance on, giving us enough information to feel confident and enough ignorance to bolster than confidence, but it does it with grace. Dividing the small time span into three sections and the country’s geography into three sections of its own proves to be an effective way to break down the themes and focuses that the game in interested in focusing on. If I were to make any complaints about the text they’d be minor. Paoletta occasionally flirts with Poe-esque prose, and while he manages it well, it is too infrequent to do more than sound weird against the backdrop of modern writing. I understand why he didn’t want to do the whole text in that voice, but the occasional use just misses. My other minor complaint is that the examples in the menagerie and ready-to-run sections actually served to weaken my sense of inspiration instead of strengthen it. Some of the creatures are similar, which makes the possibilities feel limited, given that ideas are repeated in a mere 12 monsters. And I know it’s minor, but I was put off by the fact that every monster and scenario was created by a man. My understanding is that they monsters and scenarios were offered tiers during the Kickstarter for the game, so Paoletta shackled himself a little in that respect. Still, a little curation and invited guests could have fixed the problem. Like I said, it is a minor one, and I feel rather petty pointing it out. Imp of the Perverse is a cool game and a fun text. It is neat to see a game born from the concepts of the Forge but with the modern sensibilities of design, so that the mechanics and the fiction are tightly and nicely intertwined. Paoletta is at the top of his form in this game.  Bacchanalia is a card-based story game designed by Paul Czege and Michele Gelli, and produced by Narrattiva. The game began as “Bacchanal,” which Czege designed for Game Chef one year, which used a bunch of colored and different-sized dice. Gelli then helped turn that into a card game. At least, that’s my understanding, so if I have that wrong, please let me know. The cards are beautiful in their own right with Claudia Cangini’s full-color art. In the game, players create a character who is a subject of the Roman empire and who currently stands accused (rightly or wrongly) of crimes against the empire. They are currently hiding in the town of Bertinoro from their accusers and the Roman soldiers who pursue them. Simultaneously, they are separated from their lover with whom they are trying to escape. The other thing you need to know is that it is a game of sex and violence, decadence of all sorts, as the gods Bacchus, Venus, Pluto, and Minerva are also present in Bertinoro to indulge in their own desires. Bacchanalia is a GMless/GMful game for 3-6 players, and each player is telling their own story, though the different tales can overlap and crisscross as they are all taking place in the same town. This is where I need to make clear that I have only read and studied the game, not played it, so take my observations and thoughts for what their worth. The mechanics of the game are cool and unique. Each player begins with a set of three cards on the table in front of them (these are called Deus cards). These cards determine which gods might have influence over your scene. Bacchus, Venus, Pluto, Minerva, your Accusator, the Miles soldiers, the Satyrs, Vinum (wine), and Amans (your lover) are all possible influences. This set of three cards changes--sometimes dipping below three, but seldom rising above three—through play. During your turn, you draw cards from the main deck, which is made up of cards that match the possible influences of the cards before the players. What you draw determines which of your cards is the “ruling Deus” for your turn. Having determined who the “ruling Deus” is, you consult a chart and see how your cards change, and what needs to happen in the scene you narrate for your character. The stories you tell are told in simple narration form. There is no freeform roleplaying during the scenes. Given the prompts and restrictions of your ruling Deus, you need to develop your character’s story, treating the other players as your audience. The game cleverly controls the themes and focus of your story by restricting you to ten types of scenes as determined by your ruling Deus. Those scenes will primarily bring you into a close encounter with those who pursue you (and the violence they intend), bring you together with your lover, or prompt you to describe scenes of sexual decadence. This is a game that will benefit greatly from players knowing each other or at least creating their play space so that everyone is comfortable and willing to make themselves vulnerable. Guarded play will likely end in “safe” stories or disingenuous acts of violence and sex. The game ends in any number of ways. You can escape with your lover to safety. You can save your lover but be destroyed by the forces that hunt you. You can simply fall prey to your pursuers without saving your lover. You can lose yourself to the wine-fueled revelries. Whether you are telling a love story or a tragedy can only be learned through play. That is always a feature that I love in a storytelling game. I really can’t say enough about the mechanics of the cards. There’s a lot happening with them, but never in a laborious or confusing way (once you wrap your head around what’s happening, of course). Certain ruling Dei make you discard a Deus and some make you pick one up (from the center of the table or from another player) so that the various Deus cards are shifting about the table. If you have Pluto, then it is likely that your accuser or the military will soon follow behind them. Venus will likely lead you to your lover. Bacchus and the Satyrs are interested in wine and debauchery. Only if you have the Amans Deus card can you hope to have the Amans the ruling Deus, which is the only way to escape your pursuers entirely with your lover. I imagine plays sends the Amans card floating around between players as they vie for the opportunity to save their character. The cards also provide a cool pacing mechanic. There is a single card in the deck of 62 that you draw from called the Parcae, or the fates. Whenever this card appears, you narrate a twist in your story and shuffle it and the discarded cards back into the main deck to refresh it. The Amans Deus card doesn’t enter play until the Parcae card has surfaced once, so there will always be a number of scenes before the lovers can even enter the story. Then, as the Parcae appears multiple times, the severity of the encounters with the military and your accusers increases so that once the Parcae has appeared 3 times, and the Miles is your ruling Deus, your character will meet their end at the hands of the military. It’s a simple pacing tool, but both effective and beautiful how it is left to chance to appear, just as its namesake would suggest. One of my favorite mechanics is that you can hold onto a drawn card for a turn if you want to. Doing so gives you a chance to influence who your ruling Deus will be the next turn (though of course it is no guarantee). So let’s say you have the Amans Deus card, and you want to save an Amans card that you drew this turn, hoping to make the Amans Deus card your ruling Deus next turn so you can escape with your lover. You “bow” the drawn Amans card (what would be called “tapping” is Magic: the Gathering did not copyright the term) to signify you are holding onto it. When you “bow” the card, you need to “incorporate[e] in[to] your narration a recognizable character or a peculiar location or object previously described by another player” (emphasis in original). In this way, the game forces your story to overlap with another player’s story by introducing some recognizable element from their story. This simple act will make the stories truly feel like they are happening in the same world at the same time. It’s the only time the game forces you to make such a connection (though of course you are free to do it in your narration any time). It’s a cool feature and a cool way to make “bowing” a significant act. This game was published in 2012, well before the recent spike in card-related RPGs, and it uses cards in a way I haven’t seen before or since. If you’re interested in card mechanics in RPGs, this is well worth checking out. You can still order physical copies here: http://nightskygames.com/welcome/game/Bacchanalia.  Eero Tuovinen’s Zombie Cinema was published in 2008, but I got my copy a few years ago from Indie Press Revolution, so it seems to still be in print. The game comes in a VHS case, and presents as a small board game that’s simultaneously a story game. The rules are short and direct, and the board is pasted onto a thin 5x7 canvas. The game is intended for 3-6 players and it plays out in a single session. The story you tell through play is that of a zombie survival horror film, Tuovinen taking his primary inspiration from George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. The game has some really neat mechanics, but it is a product of its day, which seems weird to say a mere decade later. Let’s start with the cool stuff. The board of the game has a single track. The zombie token begins at the earliest point of the track, and the player tokens begin 5 spaces ahead of the zombies and 4 spaces from the end. Each space describes the limits of the zombies’ power, so when the zombies are in the first space, we are told that “Zombies appear only indirectly: rumors, delusions, and newscasts, for example.” As the zombie token moves forward through play, the zombies appear first individually, slow, and limited, and as they progress, their numbers grow as do their determination, effect, and abilities. It’s a great way to pace the zombie pressure to match the typical zombie pic. The other cool thing the board allows you to do, and this is for me the golden tech of the game, is that scenes resolve by moving players forward, backwards, or nowhere at all. The game is GMless/GMful, and players take turns setting scenes and pushing for their own character’s survival. Each scene can potentially end in a conflict between characters. If it does, the characters who win the conflict get to move a step forward, and the losers have to take a step backwards. This means that your survival is dependent upon pushing others under the zombie bus. That’s cool and on brand. Conflict resolution is also neat. Each player has a uniquely-colored token and a matching uniquely-colored d6. At the time of conflict, the player initiating the conflict puts their dice forward. If the other player yields to the first player’s demands, they hold their dice and no conflict occurs. If the other player wishes to engage in the conflict, they too put their dice forward. Then the other players have a chance to affect the outcome of the conflict. Non-involved players can either pass, ally themselves, or support a side. If they pass, they hold onto their dice and stay out of the conflict. No matter how the conflict resolves, that player’s character is staying put. If they ally themselves, they add their dice to one side of the conflict. In doing so, they tie their fate (and token’s movement) to the side they ally themselves with. To support, the player places their die on top of the side they are supporting. This is a meta-action, in that the support is the player expressing their support for a side, not the character. The character doesn’t have to even be in the scene (or still alive) for the player to support one character. The supporting player’s character’s token is not affected by the outcome of the roll. Then both sides roll their pools and the player with the highest single die wins. The die mechanic is a good way to keep everyone involved and to let each player decide how they want to participate. The system also means that if you want to save your character, you need to seek out and participate in the conflicts in the scenes. It’s a smart way to make players happily create the drama the game wants to see. The zombies move ahead every round and can never be sent back, so there is an 8-round clock on the game. In addition, in any conflict in which the dice tie, the zombies take another step forward, so the odds say a game will average 6-7 rounds, with a minimum of 5. The zombies, combined with their naturally increasing threat levels, makes for an excellent timer. The main troubles from which the game suffers, in my opinion, is that it does nothing to share the heavy fictional lifting with the players. This is what I mean by the game being a product of its time. In the last 10 years, indie designers have learned all kinds of techniques to help create character relationships and material for scenes. Let’s start with character creation. The game has three sets of cards (9 in each set, 27 all together). To create characters, players draw one card from each set and will have a history, demeaner, and general appearance. Seems good. But the game does nothing to tie the characters together, so unless you have experienced players who know that the drama will benefit from ties and past relationship, expectations, and desires, you will end up with a game of strangers with nothing to talk about in any given scene except the zombies outside their door. Similarly, scene creation is left to each player during their turn with the simple prompt: “The active player makes the call on the time, location and participants of the scene like a shot in a movie.” That’s it. That’s all you’re given. There are no mechanics to help with the pacing of your story beyond the abilities of the zombies, nothing to create interpersonal drama. I can easily imagine a game in which every conflict results from character’s screaming at each other in life-and-death hysterics. It’s up to the players to create a thoughtful set of interactions, which is great is you are with experienced and thoughtful players at the top of their game. The character cards are problematic in their own way. One of the character roles is “Ethnic Minority”: “Black, brown, yellow, red, faceless stereotype. Fulfill them or not.” Yikes. I get that in white American cinema, the token character of color is a thing, but there is no reason for your game to continue that. Similarly, having that card suggests everyone else is white. Ugh. Another card is “Dependent”: “Cannot live without others. Cripples, handicapped, elderly. Can do something, though.” And of course one of your character’s defining traits can be “Mental Problems.” There’s a whole lot of cringing there. I haven’t ever played the game, and I don’t see myself ever playing it at this stage, especially with Zombie World out there. All the same, this game is designed to scratch a different itch than Zombie World does, and it has some innovative ways to get there. The problems with the game can be pretty easily solved with updated character cards, a relationship/history feature, and some basic scene-creation and conflict-creation support.  I bought The Bullwinkle and Rock Role-Playing Party Game off Ebay after Epidiah Ravachol posted a Twitter thread in which he explained (partially) why he is a big fan of the game. The mechanics and setup sounded really interesting, so I wanted to see for myself how it worked. I found a still-shrinkwrapped boxed set for less than $25 and ordered it. Not surprisingly, Epidiah was right: this is a really cool design for a roleplaying game. Many games have tackled the problem of introducing non-storytelling gamers to a storytelling game (I am of course using terminology from the 21st century, as the only words in the 80s for the kinds of games we played were RPGs), but this game has a great solution. First, they broke the game into 3 different games, to get players adjusted to what takes place in a roleplaying game. The first game uses the deck of 108 cards. The cards each have a person, place, thing, or event that happened in one of the Rocky and Bullwinkle episodes, such as “A ball of string”; “Pongo Britt, President of the Frostbite Falls Foistboinder Co.”; “Inherit something valuable!”; or “Explosive Mooseberries.” Most of the cards have an additional phrase, mirroring the punning and general wordplay of the series the game is based on. For example, “A close shave” has the subtitle “Or, just in the nick of time!” Players then select a storyline from the booklet entitled “Stories.” The players read the opening situation, the characters involved, and the ending of the story, and then deal out 5 cards to each player. (Smartly, the players then have a chance to throw out any cards they don’t want and draw back again to 5, a feature that similar card games would do well to emulate.) Then the players take turns progressing the story from the opening situation toward the ending, using the cards in their hands to inspire where they take the story. When they use an element from the card in their hand, they lay that card down and pass the storytelling to the next player. When everyone is down to their last card, game play pauses and the players think about how their card could get to the ending. The players who think they have a clever way to do it have a short competition to see who will finish the story and then wrap it up. This game takes all of two and a half pages to explain and served (I would guess) as the inspiration for games like “Once Upon a Time.” The game introduces a lot of key aspects of play. First, players can choose from any type of story from the show, meaning a Rocky and Bullwinkle story, a Fractured Fairytale, Aesop and Son, Peabody and Sherman, or Dudley Do-Right. Then players have a non-competitive, no-stress way to create a story together using the cards to lead them to say funny and surprising things. The goofier the story gets, the more fitting it is to the genre. Finally, the players learn to use the cards liberally as inspiration, not as exact things. So, that shaving card can be a literal shaving razor, a close call, someone getting cut by something sharp, or anything else the player wants to interpret it as. There are no rules for nixing someone else’s interpretation, so the card-player is the final arbiter of their contribution. The next game using foldable standees and introduces players to playing single characters in the creation of the story. Just as before, a story is picked from the book, but this time, they care about the opening situation, which characters are involved in the story, and what each one of those characters wants to achieve through the story, dividing those goals into things the good guys want and things the bad guys want. Players get a hand of cards, just as they did in the other game, too. This time, however, they choose one of the characters from the story and put the standee up in front of them. On one side of the standee is a picture of the character they are portraying, so everyone can see who you are. On the other side is a list of “powers” your character has and “Useful Sayings,” which are mostly catchphrases from the show, such as Rocky saying “Hokey Smokes!” or “Again? That trick never works!” The “powers” list tells you how your character acts in a story and what they can do. For example, Rocky can “fly,” is “nimble and quick,” and has “amazing trust.” The first says that any time the player wants, they can narrate Rocky flying. The next says that he can perform amazing feats of getting there in the last second. The third says that Rocky will believe people, even the villains if they are in disguise, have good intentions and can be trusted. You can see that the first gives them something fun to do, but the last two are about narrative conventions and fun ways to get the character into and out of trouble. I haven’t seen the show in eons, but the powers and sayings refreshed my memory even though it’s decades old and put me in the mindset of the show. A player looking at the cards in their hands and the back of their standee will have all kinds of ways to decide what to do when they are prompted. The other difference of the second game is that there is a Narrator. The Narrator is a standee card like the character cards, and the players take turns being the Narrator. The Narrator standee has a picture of a microphone on the one side, and a list of things the Narrator can and should do on the other. First, they can draw a card and discard a card if they want to. This is a great mechanic for keeping your cards fresh while still making them have weight. Second, there is a list of questions for the Narrator to ask as they please, and these questions basically set up the content and crisis of the scene: “Where is your character and what is he/she going to do?” “To what or whom are you going to do that?” “When are you going to do that?” “How are you going to do that?” “Are you going to let him/her get away with that?” “How are you going to stop that character from doing that to your character?” I think the Narrator card is amazing because it is an entire GM course on one card, and the player doesn’t even know they are GMing. Their only job is to ask questions and call for spins when those conditions are met. Yes, a spin. The game does have a resolution mechanism that kicks in when characters do something with “a real chance of failure” or when they “do something to another character” or if “there’s a disagreement between players.” Each character has their own spinner, a little cardboard card with the classic plastic spinner in the center. On each character’s card is some percentage “yes” and some percentage “no,” so that every spin results in a pass or fail state. The Yes/No ratio on each card skews heavily toward the No, which means that characters will be messing up regularly. Why? Because messing up is hilarious fun when you are telling a goofy story, and it is especially relevant to telling the type of stories on the Rocky and Bullwinkle show. In my conversation on Twitter with Epidiah, it occurred to me that the game uses all these game features that we associate with board games in play: cards, character standees, and spinners (and there are even plastic hand-puppets for being really goofy). In a lot of ways, I think the game is trying to make players comfortable with standard game pieces so that it feels like what they are doing is playing a more normal game than they really are. What I see in this game that is so impressive is how it breaks down the activities of roleplaying into these simple component parts and lets players jump in with little prep or pre-discussion. The GM tools are amazing, and the breadth of inspiration given to the players means that they will always have something fun and interesting to say when it’s their turn to speak. Hooking this system up to the Rocky and Bullwinkle show is brilliant because the show models interesting failure and is so goofy in its nature that players will not likely feel self-conscious during play or feel the pressure to make the “perfect” move. If you like storygames and like thinking about their design as creating interesting conversations, you can get a lot out of reading Bullwinkle and Rocky Role-Playing Party Game. It has influenced how I am thinking about things, and it even had a major influence on the game I designed to completion the other week. It’s a really rich game.  I’ve been playing RPGs for about 40 years. I’ve been studying RPGs for nearly 4 years. I’ve been noodling with design stuff for only about 2 years, but until now, nothing has ever made its way into a finished game. I was inspired by Paul Beakley’s #OnRampJam (https://itch.io/jam/onrampjam-igrc) and started working on my design shortly after her announce the jam. The premise of the jam is this: Provide a tool for an experienced gamer to show the uninitiated what tabletop roleplaying is, what’s fun or rewarding about the experience, what’s unique to roleplaying compared to other forms of play, gaming, and interactive art. Not surprisingly, I had Apocalypse World on the brain (when don’t I have Apocalypse World on the brain?), but I also had the Bullwinkle and Rocky Role-playing Party Game on my mind and the way it uses cards to give the players something interesting to say whenever they need it. Also back there was Sandman: Map of Halaal, and its use of cards to introduce mechanics to the players. Finally, I had recently read John Harper’s 5 Minute One on One game, which I thought was a brilliant way to introduce new players to the hobby. With all that, I knew I wanted a card-based game and I wanted to use the detective genre to cast as wide a net as possible. Who doesn’t love watching/listening to/reading detective fiction?! No one I’d want to play with, I think. I didn’t want to have any character creation, and I wanted the player, just by looking at the cards in their hand, the cards on the table, and the situation in their head to have something fun and exciting to say. I wanted the new player to not only be able to play the game but to actively build the fiction with the GM. Originally, all the cards were going to be on the player’s side, but then I decided the GM should have a hand of cards that functions similarly to the player’s. This arrangement would make it clear that both players were equal participants in the game, with a different focus but with the same basic tools. As I developed the game and talked it over with Ann, my wife, I decided that the game could not only serve to introduce new players to the hobby, but if the GM cards were done well, it could be a game to introduce experienced players to the role of GM. I loved that idea and ran with it. The resulting game is “Dorm Detective” (a weak pun on the phrase Dime Detective—I’m not proud). Because some cards needed to have a front and a back, the resulting document is 8 pages long, which when printed out are 4 double-sided pages. Since the jam was specific about the 1-2 page length, I decided against submitting the game to the jam. So instead, I thought I’d share it here. I am not a graphic designer, so there is nothing fancy in the layout or presentation. It took me 12 hours to lay it all out as it is. I can’t imagine how long designers take to make their stuff look appealing in addition to being playable. I welcome your thoughts and feedback, and will be happy to answer any questions! Thanks for reading!